WENDY CARLOS

The Burden of Faltering Genius

by Mark S. Tucker

(May 2007)

Much contributes to Wendy Carlos' current near-total lack of presence in the larger music world, not the least of which has been her ages-past decision to transfer out of the gender she was miscast in, a decision that appears to have, unsurprisingly, dogged her to the present moment. Expectedly, obnoxious hounds have nipped at her heels, baying at the Tiresian quandary, to which she has responded in a largely lamentable manner. But there's also the matter, historically, of an increasingly deteriorating musical output, a misfortune always tending to secure indifference no matter how bountiful one's past may have been.Neither of these is a justification speaking cogently to the record though. As Carlos herself anguishes, it's to that Rosetta Stone she would be most relieved if people would redirect their attentions and, of course, she's quite correct. On the other hand, no one seems to have informed the estimable Carlos that this is Earth, an entropically dark Not-So-Funhouse despite the pretty wallpaper. That it's a lunatic mudball infested with loutish top-of-the-chain lifeforms most elegantly characterized through predatory ignorances that would affright even the most grossly narcissistic mythological gods is inarguable. So, where's the surprise?

All that's as may be and shouldn't have the least impact on proper regard toward a string of releases standing as one of the brightest niches in American, if not world, music history. It's to that record we'll repair, to wallow in magnificence of an order not often afforded mortals, building an offramp away from the mainstream of prowling brickbrains and their monkey chatter.

Wendy Carlos was born Walter Carlos in 1939, a child prodigy and one of those spirits who enter the realm armed with the sort of talent and intelligence the rest of us can only stand back from and marvel at. At six, he'd begun playing piano, four years later composing "A Trio for Clarinet, Accordion, and Piano." His interests, though, weren't confined to music, and so he started an exploration of the graphic arts and sciences. At fourteen, he'd designed and built a small computer: this was 1953 and most adults hadn't Clue One what such a contrivance was. Three years later, the young intellectual constructed a studio to hybridize electronics and music, producing his initial electronic work, composed of tones manipulated on tape recorders. While compeers were sporting about in baseball leagues or waxing moony over some skinny mafia crooner on the Victrola, Carlos was engrossed in advanced speculations about the nature of sound and the importability of science into art.

But this wasn't sufficient for the young lion, so, at age 23, he entered Brown University, to study not only music and physics, but to informally teach electronic music as well. This went so swimmingly that, in '62, a transferrence to Columbia University was effected, therein immediately producing an induction into the prestigious Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, at one point assisting Leonard Bernstein at the Lincoln Center Philharmonic Hall in an evening of electronic music. At Columbia, he was taken under wing by the much-famed Dr. Vladimir Ussachevsky. The good doctor not only recognized superior mentality when he saw it but encouraged such things as much as possible, allowing Carlos and compeer Philip Ramey the run of the sonic laboratory after-hours. In that sacred space, Carlos immersed fully in his work, feverishly composing and experimenting. From this emerged "Dialogues for Piano and Two Loudspeakers" (1963). 1964 saw "Variations for Flute and Electronic Sounds" and "Episodes for Piano and Tape," while 1965 produced the humorously titled "Pomposities for Narrator and Tape," as well as the operatic "Noah," which blent electronics into a conventional orchestra basing.

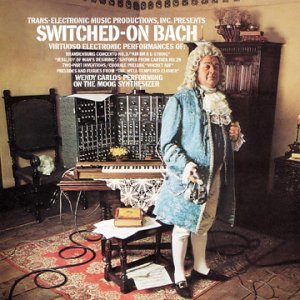

Carlos left academe to explore the outside world, becoming a recording engineer for Manhattan's Gotham Recording Studios. There, he began an association with Robert Moog, intent upon obtaining a refined point for his desire to bring the piano into its next incarnation. This naturally led to his discovery of Moog's synthesizer and its potential for the composer's tonal applications to Bach, whom he felt was owed the honor. The synth offered unparalleled possibilities. After three years of determining what was what, Carlos formally entered the music world with the surprise 1968 release Switched-On Bach, an LP that made huge waves planetarily, selling like a fiend. For a few moments, the Beatles had a rival: Walter Carlos, who garnered attention not only from the expected rock world, which was as deep as it could then get into the use of synthesizers, but also from stodgy classicalist halls, going gaga over the album. Around the world, Switched was found to be spellbinding, compelling, and unavoidable.

Little wonder. Carlos had clearly demonstrated most of the cardinal virtues synthesizers were capable of, states human performers were constantly striving for but, being mere biological units, mostly unable to attain - such things as absolute consistency, perfection of tone and pitch, flawless execution, and many other virtues falling well outside the purview of constructs with muscles and nervous systems. From the opening seconds, the listener was thunderstruck by the inhuman precision, speed, and pristinity of the instrument as sounds flowed out in colorations never before heard. Carlos' long years of slaving under the Muse had paid off: here was true wonder. Morton Subotnik might have beaten her by a year, with his astounding Silver Apples of the Moon, but Carlos ratcheted up the ante by daring to embody one of music's two most hallowed gods, Bach (the other being Ludwig Van), and with such inimitable perspicacity that not a whiff of outrage or academic sniffery was registered by anyone boasting more than two brain cells to rub together.

It wasn't merely the synthesizer's arresting palette which captured the consumer's fancy, but Carlos' letter perfect understanding of the deeper mathematics and many levels of Bach's ceaselessly fascinating work. Where the opening "Sinfonia to Cantata #29" stunned the listener into a cyborg world of the alien and familiar, the follower, "Air on a G String," demonstrated an extremely perceptive ear drenched in electronic sensitivities performers with traditional instruments would be exceedingly strained to duplicate. The synth's ability to generate nuances impossible to acoustic instruments weighed heavily in the mix, but Carlos had so subsumed its oft cold nature that the midground he tread was a new dimension.

Perhaps that explains the fascination with the LP. It was an entirely new creature, taming the wild farflung timbres of the remaining electro-pioneers back down to a recognized canon. Those who hadn't the breadth of imagination to appreciate his electronic contemporaries' bizarrer output could fall rapturously into Switched. Taboo hedonisms within the emerging genre were now acceptable, the mainstream classicalist fetish for propitiation and the need to prostrate before antiquity greatly assuaged.

Each cut of Switched is a wonder, whether one revels in its modernization of ancient scripture or in the xenophilic sensuality of broadly dimensioned tones breathtakingly captured and massaged to perfect presentation. To this day, the music hasn't lost a jot of the unearthly luster it jolted the globe with in 1968. Though there have been many very good and very bad follow-ons by sundry others - all eager to find the accompanying cash windfall rightly accorded Switched - none have matched Carlos. No less a genius than Glenn Gould bowed before it, but with the usual artists' observance of competition by way of underspoken acclaim, calling it "the LP of the decade." It is, in fact, one of the all-time most remarkable music releases, Gould notwithstanding. It was also the first classical album to go platinum in recording history.

That it would spawn a series of follow-ups by the composer can only be seen as a blessing. Where most artists would've been content to rest in prolific laurels, producing a diminishing string of ever-devolving knock-offs, Carlos produced The Well-Tempered Synthesizer (1970), dropping Bach to second-string status whilst indulging a love for Scarlatti, Monteverdi, and Handel. The raffish cover, showing bewigged ancients in an ultra-modern computer cleanroom setting, gave an indication that Carlos was going to be a bit more playful with the material, and so he was. The songs are more elastic, stretching liberties tautly, but still fully attentive to the each hoary chestnut as an icon. In fact, a couple of cuts, like Handels' "Air," have a few rather surprising declensions and twists, keeping Synthesizer as idiosyncratic and arresting as Switched, showing Carlos in full glory, unleashed to wreak Art upon the world. The LP, however, didn't even begin to hint at what was to come.

Apparently, the maestro had been not only pursuing college sciences but studying the secrets of the neutron bomb, for he dropped two on us a couple years later (1972): the soundtrack to Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece, A Clockwork Orange, and the monumental Sonic Seasonings. Kubrick, an aficionado of classical music, as all his movies have evinced, had caught Switched and been more than slightly intrigued. For Orange, Carlos composed new transcriptions but also, in a couple cases, broadly re-interpreted classics to go alongside Kubrick's superb Deutsche Grammophone selections. These twin contemporaneous genuflections to antiquity, along with a couple of popular pieces - Gene Kelley's "Singing in the Rain," put to appropriately blasphemous use in the movie, and the bizarre "I Want to Marry A Lighthouse Keeper," serving as a searingly subtle piece of social commentary - fit like hand in glove, making for one of the most bizarrely attractive soundtracks of all time. But, most striking was the LP's far-too-short extract from Carlos' "Timesteps," still one of the absolute masterpieces of electronic music.

His interpretation of Purcell's "Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary" is astounding and, as with "Timesteps' truncation, far too short. One of the darkest most lamentive title songs ever (thus) altered and employed, it's marrow-depth spooky, heart-wrenching, and should've gone on for at least ten minutes. Rarely has such a statement been so engrossingly re-crafted. The blend of electronics, as main instrument and as complementarily atmospheric ornamentation, is a ne plus ultra of the catalogue. "Timesteps" is as chilling as an arctic plain while unflinchingly cosmic and dark, careering through space and human emotion like a burning planet. Easily the equal of a Xenakis, Subotnick, or Penderecki composition, weighing in at only a fractional 4:13, it overwhelmed the listener.

Did I say there were only two singularities that year? I lied. There was also, unknown to most, an ill-distributed Walter Carlos' Clockwork Orange companion LP, also published by Columbia Records, featuring the entire 14:30 "Timesteps" along with the rest of the Orange treatments and one song more, something not used in the movie, co-composed in tandem with long-time producer Rachel Elkind: "Country Lane." To those fortunate enough to have lucked upon the LP, grabbing a copy (it didn't stay long in the racks, appearing to have been an extremely limited printing), here was treasure indeed, to be placed reverently alongside Stockhausen and sibling companions on the progressive/avant/neoclassical shelf.

"Timesteps" must be heard by anyone even faintly interested in electronic music. An episodic masterpiece of the first water, it ranks with the 25 best original electronic realizations in music. Extremely deep, illuminated in its spatiality, the composition contains huge parameters for the many gestures, statements, and environments Carlos writes into it. Perpetually active, the song's a highly described diorama constantly shifting through abstracted planes. Nor is "Country Lane," that dropped tune, as pedestrian as its title implies. Dramatic, proud, confident, the composition marches and struts in magnificent raiment like an amused deity across the skin of the world, observing the vain human comedy beneath it. That whole LP is a perfect companion to the sanctioned soundtrack, measuring up in all ways, but with the delicious addition of almost-forbidden fruit. To some few, it occupies as solid a place in hearts and minds as the Beatles' Sergeant Pepper's, King Crimson's In The Court of the Crimson King, or any other defining moment in vinyl.

Those not being enough, the year was rich in artistic red-lettering going ultra-crimson in the release of Sonic Seasonings, the first true work of ambientalism, ushered out just prior to Eno's equally landmark Music For Airports. Seasonings was what was then termed a 'mind-blower'. It still is, all the more so since it's re-release and the addition of another forty minutes of retrieved period material. Carlos had taken Vivaldi's idea, removed the standard classical brainworks and then outrageously tossed away the corporeal husk. Seasonings is The Four Seasons composed by Walt Whitman through Carlos Castaneda, a work never rivaled nor ever again seriously attempted, though New Agey bumblers would scramble endlessly to land weakly in the ballpark, to disastrous results. Blended of environmental recordings (apparently there really was demonstrable use in the idea behind all those fluffy Environments field recordings otherwise relegated to the 'mistaken purchase' ashpile in everyone's collection) and music, Carlos ran through a small thesaurus of techniques. "Spring" is actually a long prelude - each piece in the entire LP hits around the 20-minute mark - with chirping birds and thunderstorms surrounding moody languid themelines offset by even lazier washes. Not terribly involving, it's nonetheless pleasant and an innocuous set-up for the next cut.

"Summer" shifts tone immediately, not radically but significantly. Belching frogs, chirruping crickets, and far-hidden marsh birds cavort amidst a standing coruscation of heat waves. Everything seems normal, a pleasant dog day in August, until flying saucer arrive and all is revealed not to be as it seemed. A flotilla of the crafts hover, unthreateningly but mysteriously descending in droves as nonchalantly as a blithe churchyard abbot making rural house calls. Like "Spring," "Summer" follows in a continual buildup of theme, a long drawn-out process leaving little undetailed. Also like the previous cut, a central intensification releases and draws back. In this case, the aliens knock around for a bit on some unguessable curiosity binge, austere visitants on vacation perhaps, then exeunt.

"Fall" initiates almost as a lushly as "Spring," maturing the life cycle, preparing to head into the downward year-end spiral. Natural elements arise in full strength, singing in wide panoramas, but gusting winds soon enter, the marker for an approaching blizzard stealing up behind. The cycle ends in a wistful look back before heading into the glacial. "Winter" doesn't rush headlong, it flows in slow waves, first chilling down the landscape, then freezing it in layers. Everything quiesces, an infinitely patient malaise sets in, ice abounds, trees stand bare and sullen, wolves begin to howl, and ghosts waft through a denuded forest. As with "Spring," something's happening but what that something might be is largely unguessable, only approximated through extended senses, the mysteries Nature never explains. As the tableau closes, we're left with much to ponder.

Seasonings didn't sell anywhere nearly as well as it should have, certainly nowhere as prolifically as Columbia had desired, and so it was back to the drawing board, to the tried and true: Switched-On Bach 2 (1973), an LP that paid more attention to Carlos' interpretations of standards, and one that tended to slow the initial record's breakneck pace. The recording is warmer, more natural, perhaps just the merest trifle too much so, as the faux harpsichords in "Selections from Suite #2 in B Minor" veer dangerously close to the dreaded instrument's true, stiff, clashy, acoustic tones. High-speed chases and rounds emerge as blindingly as on the first LP, but Carlos more readily explores less showy compositions, displaying the Moog's place in non-Escher-esque settings, making a first stab at the daunting Brandenburgs, consuming all of side two, fully re-investing the multiple levels of the debut LP.

Though more inviting, 2's engineering wasn't quite up to the Valhallic levels of its brother. It also bent the knee a little more obeisantly to tradition than audients with bolder appetites would've preferred. It seemed desirous of procuring a place in classical esteem more securely. This was cured when Carlos By Request (1975) was issued, where Bach played second banana to Carlos himself, accompanied by Tchaikovsky, Wagner, Bacharach, and the Beatles. Request was an interesting potpourri, containing an intriguing take on Lennon & McCartney's fascinating "Eleanor Rigby" before turning to a broad circus swipe at Bacharach's penchant for twee-ness by turning "What's New Pussycat?" into the pretentiously rude carnival sideshow it really is, planets removed even from Tom Jones' bellowing recital.

The classics again took center stage but no longer as stratified as had earlier been the case. Carlos, in impishly concocting "Pompous Circumstances," is allegedly penning "Variations & Fantasy on a Theme by Elgar," but it's no such thing; rather, Ravel is thrown in with the Beatles, Joplin, and many other familiars, turning into a shifting calliope, an oft dark-ish Big Top, making a misshapen soufflé unlike anything which had previously appeared. The composer also showed free-wheeling origins more readily, as the LP features takes on two earlier self-compositions and a new song, "Geodesic Dances," all neoclassical, worthy of study, quite distanced from classicalist formularism, and allying strongly with contemporaries. Unfortunately, these mostly unknown pieces form what was to be the commencing contrastive point for an oncoming output of second- and third-rate work. Up to this point, there had been an élan and freedom that distinctly carved out a distinctive niche, whereas later (especially the most recent) CD's can only be called 'pitiful' in comparison. But, to that momentarily.

Four years passed. By the release of Switched-On Brandenburgs, Walter had become Wendy. The controversy in that was first mirrored in CBS' relegation of her name to tiny print at the top of the LP, almost crowded off by the artwork (by engraver James Grashow, most famous for his Jethro Tull Stand Up cover) and illustrative of the usual craven corporate fear of controversy, preferring to insult artist rather than incite public, refusing to accept the situation - dollars, not respect, being the only real goal. Carlos and Elkind solved several sonic problems here, irritations which had somewhat vitiated earlier takes on the second and third concertos.

The 2-LP presentation is simultaneously worshipful while irreverent - sprightly, vivid, decorous, multi-level, colored in unearthly tones that nonetheless reek of soil and air, category-bending, and, above all, stunningly executed, residing in the usual soul-deep reflections Carlos always accorded the masters. Allan Kozinn conducted a very illuminating short interview in the liner, demonstrating just how excruciatingly wrought some of the realizations were. Once again, Carlos had awakened the classical world, and acclaim was instantaneous, even despite an audience rapidly jading with a plethora of imitative releases by poseurs through the years since Switched 1 and 2, mostly knock-offs by tin-eared wannabes. With Carlos, fidelity to score was paramount, but not so much so as has been heralded: the careful listener will find a surprising amount of "improv" all the way through the readings, many being embellishments taken through electronic warps. An immersion in the set is as rewarding as Sonic Seasonings, if only for pure hedonism.

This, however, was to mark the end of The Carlos Era (which, all other writerly praises aside, rightly deserves 'proper noun' status). Her next release was of work she'd done for the futuristic Disney movie Tron (1982), consisting chiefly of throwaway colorations, enhancements, and the usual movie thematics, much too diddlingly mainstream for any serious consideration, though apparently valued by animation enthusiasts and Trekkie types.

Digital Moonscapes followed in '84 and seemed to mark a possible return to classicalist origins, but this was not the case. Carlos was New Aging. Ironically making excellent observations in the liner notes re: the narrow confines of synth playing, she then concocted compositionally claustrophobic pieces that knuckled under to the same emulated bandwidths she, only moments before, had been lamenting. From this point on, it would be obvious that when Ms. Carlos was not harmonizing with classicalist genius, she had little to say, having puzzlingly forsaken the brilliance of her earliest self-comps. Now, she'd join the ocean of Debussy/Ravel-inspired Sopor-artists, the 'Let's all copy each other!!!' New Age herd.

Pretensions to classicalism abounded but the profundity had vanished, glib facility replacing it. The patch choices became thin, weak, and bloodless... and the engrossing ornamentations so beautifully appointed before this? Dead. That not sufficient, she aped Beaver & Krauses's ancient Nonesuch Guide to Electronic Music in her Secrets of Synthesis (1986). Like its forebear, Secrets was a spoken-word/waveform demonstration LP and tanked just as badly. The probability of its unsaleability seemed apparent, for Beauty In The Beast was put out the same year as an offset. That LP has its moments, namely the first two cuts, highly interesting forays into electronica in league with material from the Soleilmoon label, but rapidly evaporates into the cliché and noodly. Sour sharped-out atonalities substitute a strange empty titillation in place of the customary insights and dexterities. Worse, the twin problems of World and New Age musics force their attentions hamfistedly. Released on the tepid Audion label, it is, other than owner Larry Fast's top works, the best LP the label was capable of, but still well below Carlos' high-water. No matter how one looks at the release, it's not bad music within the overcrowded genre, but not good Carlos.

And that's the byline that can be stuck on the rest of her output to date (Switched-On Bach 2000, Tales of Heaven and Hell, etc.): passable but not great, certainly bearing little resemblance to her establishing oeuvre. Like many artists, Wendy Carlos appears to have eclipsed and waned, satisfying herself with somewhat pleasing but easily overlookable work. The last releases are little different from the bulk of similar CD's by a thousand nameless laptop and Emulator wonks, just more capably recorded. None of this, though, should be allowed to interfere with her rightful place in music history. When all's said and done, unbiased by gibbering interferences from the id of the public, Wendy Carlos deserves a sound unshakeable place with the best artists that America, or Earth for that matter, has produced. A purely analytical viewpoint will readily prove this.