Velvet Underground

Norman Dolph interview

by Richie Unterberger

(June 2009)

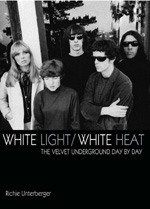

White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day by Day, available from Jawbone Press.

The Velvet Underground & Nico--colloquially known to the ages as "the banana album," in honor of its distinctive Andy Warhol-designed cover--is today recognized as one of the greatest and most seminal rock albums of all time. Until relatively recently, however, the contributions of one of the figures most responsible for arranging and running the April 1966 sessions yielding the majority of the tracks have been relatively unknown and overlooked. While Norman Dolph takes no credit beyond his due for the groundbreaking music unleashed on the banana album, it was he who procured the studio time, co-financed the recording, and essentially acted as a co-producer of sorts for those sessions.

When he crossed paths with the Velvet Underground in early 1966, Dolph was a sales executive for Columbia Records, his main job being in Columbia's Customs Labels Division, which provided services for smaller labels who didn't have their own pressing plants. He'd recently made the acquaintance of Andy Warhol in the course of his side job of supplying music with his mobile disco for art gallery shows and openings. He'd also noticed that one of his accounts, Scepter Records--then most famous as the home of Dionne Warwick, having also landed quite a few '60s pop and rock hits with the likes of the Shirelles and Chuck Jackson--had its own recording studio.

When the Velvets and their management were ready to record their first album in April 1966, it was Dolph to whom they turned when they needed to acquire professional studio time. For good measure, Norman also split the costs for the sessions with the VU's management. He even, along with engineer John Licata, ended up pretty much running those sessions, though neither he nor Licata were credited on the original LP (an omission rectified on subsequent editions in the CD age, where both were eventually credited as engineers).

Nine songs from these sessions--which took place over the course of a few days at Scepter Records Studios, probably spanning approximately April 18 to April 23 of 1966--were almost immediately pressed onto an acetate that Dolph took to his employers, Columbia Records, in hopes of gaining a record deal for the Velvets. Columbia in turn almost immediately turned them down. Yet the takes used for six of the tracks ("Femme Fatale," "Run Run Run," "All Tomorrow's Parties," "I'll Be Your Mirror," "The Black Angel's Death Song," and "European Son") on the acetate were eventually used--with some remixing on the banana album when it was finally released in March 1967, though the three other tunes on the acetate ("Heroin," "I'm Waiting for the Man," and "Venus in Furs") were re-recorded after the Velvets signed to MGM in May 1966. Now widely bootlegged, an original copy of this acetate sold on eBay for around $25,000 in December 2006--one of the highest prices ever paid for a disc of any sort containing musical recordings.

I spoke at length with Norman Dolph about the Velvet Underground's April 1966 recording sessions on December 16, 2007 for my book White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day By Day, a comprehensive chronology of the Velvet Underground's career drawing on nearly 100 first-hand interviews.

Q: Had you seen the Velvet Underground before you recorded them in the studio in April 1966?

ND: I'd done a little more than see them. Back in that point in time, I had started what was the first mobile disco in the New York area, for all I know the first one in America. I was doing mobile disco around the area, all kinds of places, and I did a lot of mobile disco for artists and dealers in the art world. That's how I first met Warhol. I had done parties for him and parties for his dealer, and that sort of thing. And propitiously in those cases rather than taking cash, I took a little picture. I've always been an art collector, and I am now, and so I would do opening parties and loft parties and all kinds of things in exchange for works of art. When they did the thing at the Dom, they used me to do the sound in between the sets of the Velvet Underground. The Velvet Underground would have fairly long sets, as I recall, and I would play disco in between for twenty to thirty minutes, something like that. So that is how I first encountered the group, doing the in-between music at the sets at the Dom [on St. Marks Place in New York's East Village].

Q: What were your impressions of those shows at the Dom, where the Velvet Underground had a month-long residency in April 1966?

At the Dom, it was really effective in terms of the layout. You had an impression of a light show as something totally revolutionary independent of the music. But the music was clearly without precedent. I don't think I or anybody had heard anything like it. My own reaction, it would have to be just, "My god, what is this?" Because the whole experience, between the music and the lights and Gerard Malanga with the whip...he would carry around a 16- millimeter projection, a huge actual projector, and shoot images on other people and on the wall. If the word "psychedelic" had any meaning at all, that's what it was.

Q: It's been reported that you helped name the Velvet Underground's multi-media performance the Exploding Plastic Inevitable.

Yes, that's true. The question is whether it would have been the Erupting Plastic Inevitable or the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. Warhol was not at that meeting, as I recall, but [filmmaker and Velvet Underground co-manager] Morrissey was. That was kind of the preliminary chit-chat about the recording sessions and the nights at the Dom. It took place in my apartment on 56th Street, and there was John Cale and Sterling...I don't believe Lou Reed was there, and Morrissey came to the meeting a few minutes late. I forget what we were talking about beforehand. The whole meeting didn't take a half an hour.

Morrissey came in, and he says, "Oh, we're thinking of this name, which do you like better? Exploding Plastic Inevitable, or Erupting Plastic Inevitable?" I think he asked around if anybody else had any other ideas. But that was the first thing he said--"Oh, I've been with Andy, and I like one, and Andy likes the other. What do you think?" It was just about as casual as I've just told you. It was not a big "let's all take a vote" kind of deal. But when Morrissey entered the room, he presented us with two choices. Really, we weren't gonna have any vote in what the choice was, other than just "what do you think, blah blah blah." I think that Morrissey said, "Yeah, we'll go with the Exploding Plastic Inevitable." Whether that decision had been taken officially at the meeting that Morrissey had with Warhol beforehand, or if it was still in flux, I don't know. But the impression I got was Morrissey had kind of made that decision, or Andy had it imposed on him, but it was made by the time that meeting took place.

[Author's note: the decision might have been made at the last minute, as the very first Village Voice ad for the Velvet Underground's Dom shows on March 31, 1966 announces, "Come blow your mind. The silver dream factory presents the first Erupting [sic] Plastic Inevitable with Andy Warhol, the Velvet Underground, and Nico." Thereafter, the event was always referred to as the Exploding Plastic Inevitable.]

Q: When did the Velvets and their management start talking about recording tracks in the studio?

It seemed to me that at the nights at the Dom, the first or second, Warhol said, "Oh I'd like to make a"...Let me just run off at the mouth a little about Warhol. I certainly can't number myself among his closest friends, but I knew him probably as well as many people do, and he was a genuinely gentle guy. Regardless of whatever's said about him, I never certainly heard him scream at anybody. And you had the feeling that there was nothing sexual about him at all. It was as though he were a college professor at Amherst or some such [thing], you know what I mean? And about 80 years old, in that sense, from the point of view of dynamism and all. He was very soft-spoken, he always laughed when he talked, and you never knew when he was serious or when he wasn't, because I think the line between what it serious and what isn't actually probably ends with Warhol in human culture.

But he said, "You know, well, we'd like to do an album of them, a record." At that time, I'm working for Columbia full-time. I said, "I can help you with that." He said, "Oh really? Okay, good. Do it." I think he did that with a lot of people, to the extent that if he found somebody that could do what he wanted, he'd just say, "Do it." And they would, whether it was appear in this movie or go out for pizza, whatever it was. He never gave a lot of orders that I ever saw. He just made suggestions and people took him up on it. He had plenty of people around there to do anything he wanted.

So since I was in the record business and I said, "I'll take care of that," he said, "Oh, great." That's the beginning and the end of the suggestion process from my knowledge. He didn't ask me any questions about do you know this studio or that engineer or this producer or any of that. It was none of that. It was, "We'd like to make a record," and I said, "I'll take care of it."

Q: There's a letter from John Cale to a friend from December 2, 1965 indicating that the Velvets were making demos for Tom Wilson, who was a producer for Columbia at that point. Were you aware of anything like that happening, as you were also at Columbia then? And is it possible they wanted to record this material with you and submit it to Columbia because they had some kind of prior connection with Wilson, who did end up signing them to MGM shortly afterward?

If there is a letter dated '65, I certainly know nothing about it. To get a little ahead of the story, we cut this reference acetate [from the April 1966 sessions], and I sent it to Columbia, along with a cover letter to the A&R department to determine whether they would be interested in the group. I got the acetate and a rejection notice back very swiftly saying that no, they were not. But it was not, to the best of my knowledge, expressly directed at Tom Wilson. It was directed at A&R in general.

Q: It seems that the Velvet Underground wanted to record an entire album for prospective commercial release at these sessions, and not a demo to be used for getting a record contract. Is that correct?

I think the thing that supports that theory is that at no time was what we were doing ever referred to by anybody as a demo. I mean, they were going for the jugular. They wanted to make a record that sounded like they sounded--it was not a demo for anybody. It was a record that they were making.

Q: What was your specific role at the actual sessions?

I was not the producer in any sense that Quincy Jones is a producer. The only thing I would say is because they were doing it on my money--and we had limited time resources fiscally, 'cause we were always bumping up against commitments that Scepter had in the studio--that I kept the thing on the rails. And it's also quite highly probable to say if they had made the same record, and I had not even been anywhere near it, it would have been ultimately played out the same way. But I think part of the way the record sounds the way it sounds is because of [engineer] John [Licata] and I keeping it on the rails, to keep the damned thing going and moving. You know what I mean--"okay, next take, let's do it, blah blah." I think that's my contribution as a producer.

Q: What were Scepter Studios like as a place to record?

It was a small floor to begin with, half of which had been converted into this studio. And there was a long hallway; on one side of this hallway were offices. The other side of this hallway, they had walled up and made into this studio. The control room had a glass wall looking into the studio, and it also had a glass wall looking out to the hallway. Some people could walk by and kind of see what was going on in the control room, even though they couldn't really see what was going on in the studio, unless they happened to stand in a particular place to be able to look through the window into the control room, and out again into the studio. [The] studio had a two-track [machine] and a four-track [machine]; the master was four-track.

The studio itself was small, certainly by contemporary studio [standards]. But they often recorded fairly large ensembles. They recorded a big orchestra behind Dionne Warwick, and they recorded gospel choirs in there. But they were always very crowded. It wasn't Columbia's 30th Street [studios] or some such. Once you had everybody in there, they had to pretty well stay put, because there wasn't a lot of room to move around.

It seemed to me that the instruments, as heard live in the studio as opposed to on the other side of the glass, were being played rather loudly. You would ordinarily expect if they were gonna play that loud, they would be in a much larger room to get some isolation between one and the other. But there could have been little separation or isolation in any kind of modern sense in that room, considering how loud they were playing. The adrenalin quality of it, I think, was because we knew had eight hours, and they wanted to get on with it, and I wanted to get on with it. Anytime they'd break down, I'd stop the tape and we'd start over. I don't think there are two different complete takes on more than one or two songs. I'm not even sure the breakdowns were saved. They may have just reused the tape.

The control room was not very large, either. I remember Licata was there 100% of the time, and I'm there 100% of the time, and Morrissey was there much of the time. And Warhol was there on occasion. He would come, and he had his little tape recorder, which he carried all the time. I seem to remember him there probably for about two hours in the aggregate over maybe three occasions. We did the work over parts of four days.

Q: What did Warhol do at the sessions themselves?

He was totally fascinated by what was going on, and I don't think he made any aesthetic judgment whatsoever. "Oh I like this better than I like that," or "Gee that sounds good" might have been it. He was a spectator.

Q: Could you talk about the roles of the individual Velvets in the recording?

They were quite clear what they wanted to do. There was never, "Well should we do this, should do that, oh, I don't know, what do you think?" None of that. There was, "let's do it," you know what I mean. It was very forthright. You had an impression that Sterling [Morrison] was an important pair of ears in all of this. I don't know that anybody really told Lou Reed what to do or what they thought or whatever, but you had the feeling that musical decisions were being made largely by John Cale. But that it was sort of in conference with Sterling. Moe [Tucker] was very quiet in the whole thing. I don't think I heard her speak ten words. She might have spoken with them on the other side of the glass, but when she'd come in to listen to something, she'd stand there and listen and then go back. She was a very quiet woman. And Sterling too was quiet, but you had the sense that he was not ignored.

I would say anything to do with a vocal performance where Lou Reed is singing, nobody influenced that at all. If it was a thing where he was the focus of what was going on, he was it. But to the extent that it involved an ensemble, I would think that the credit fell to John Cale. You had the impression that John Cale was a studied, learned musician in the sense that he could read scores and all that sort of thing. Whereas Lou Reed was essentially a performer. I don't mean that derogatorily, but he was the Mick Jagger of the deal, whereas John Cale was the Keith Richards of the deal. I would not say that Moe was the Charlie Watts of the deal, but Sterling was clearly the Ron Wood of the deal.

Q: Though Sterling's primarily thought of as a guitarist, he actually played a lot of bass on the record, especially when John was on viola. How did you rate him as a bass player?

I thought he was quite good. Because to me, the pieces that made the most impact--if I close my eyes and think of the session, the first thing that comes to mind is the pieces where John Cale is playing the viola. Because those drones and eastern figures that he'd create, which had to have that bass behind him, were just as locked in as you could imagine. And so I don't have any real recollection in my mind of Sterling as a guitarist. I see him in tandem, in my mind, with John Cale.

Q: How did the band approach the three songs on which Nico sang?

In the actual sessions, you didn't have that sense that she was being treated as a centerpiece at all. She was treated, I thought, at the sessions with great respect. In other words, things went into sort of a quiet mode when she was there. I don't believe she was in the studio much longer than when she was performing in the studio. She may have sat over in the corner a couple of times, but space was kind of crowded, and there wasn't room enough in the control room for anybody to loiter beyond the two of us [Dolph and Licata], and maybe either Warhol or Morrissey or both, which would put four people in the control room. I remember when she was in, she was singing, and when she was not singing, she was not heard of.

If you imagine [jazzman] Les Brown and his band of renown, and Doris Day as their singer, you know what I mean. When Doris Day came on, it was not as though she was a modernaire or something; she was a special focus of what that group did, or that orchestra did. I think that is a very accurate characterization, that they viewed her as a jewel in a setting, and it was in no way slapdash or quick or "let's get this broad out of here." It was none of that. It was, "Okay, well, now we're gonna shift into a quieter gear, and we're gonna do Nico," and that was the way it went down.

It seems to me that "Heroin" was either done last, or [as] the very first [song] of the second day. 'Cause I remember that that was the one where Lou Reed needed to kind of get his head in the right place for that. And I remember in that one, in the control room, nobody moved a muscle when he was singing that song. And you didn't want anything to go wrong with that take at all, because if it had, he would have torn a wall down. Every bit of the energy in the song, you experienced in his persona at that point.

Q: It seems that the sessions went very quickly, and were pretty reflective of how the band sounded live.

Most of the actual tracks, there was only one good unbroken take, maybe two of some of them. I'll say this: at no time did anybody on either side of the glass say, well, we'll fix it in the mix. That was never said. They performed it, and they'd come in, and we'd play it back end-to-end. If there was not a simultaneous agreement, they'd go back and do it over. But usually, anything that sounded like rough or iffy or from an engineering point of view didn't please John, he or I would break it down. We'd never even finish the take. Then they'd start a new one over, and then they'd come in and say, yeah, that's it, next case.

And there was never any "I'll play it back tomorrow, see if I like it tomorrow, and if I don't, then I'll redo it." None of that. It was all just like they'd just sung it live, and they couldn't go back and redo it, because it was live. Because we were paying for the tape at probably $125 a roll, usually the broken takes were backed up and recorded over. Otherwise there would be some interesting scraps lying around.

Q: What was John Licata's contribution as engineer?

He was a wonderful, cooperative, and easy to get along with, unfreaky guy. He was the total antithesis of the Velvet Underground. He was a journeyman; the next day, he was onto something else. I mean, it was just like a day's work for him. John Licata, he deserves the credit, because at no time did any of the musicians ever tell him what to do. It was as though they went in and played, and he got what they wanted. And they came in and said, "Yeah, that's it." It was no niggling or diggling or any of that. He got that sound.

Q: After you submitted acetate to Columbia on April 25, 1966, what was the label's reaction?

Their reaction was parsed in corporate terms--"you're out of your mind with this." They had zero interest in it.

Q: Do you think it might have been a blessing in disguise that the Velvets got turned down? When they signed with MGM shortly afterward, even though the label didn't promote them well, they gave them virtual total artistic freedom. Would Columbia have done that?

Look what they did with Aretha Franklin, or a lot of people. Even for my money, the Dave Brubeck records on Fantasy are I think even better than Brubeck did on Columbia. Columbia always moved artists to the middle. Dylan and Bruce Springsteen are exceptions, but they tended to move artists in the middle. And I don't think that would have worked well with the [Velvets]. So I think they were far better off, rather than going to Columbia, to wind up where they did.

Q: MGM/Verve did seem to leave the group's music alone, essentially.

Yeah, they did. And they packaged it well. You can't say they did a cheap and dirty job. Because those gatefold covers with the peel-off [banana] and so forth had to have been very expensive relative to what a jacket could have cost. There was some seriousness behind the effort.

Q: Do you know if the Velvets and their management approached other labels to get a deal between the time Columbia turned them down and MGM signed them? Sterling Morrison remembered Atlantic and Elektra turning the group down before MGM made a deal.

No, I don't, because after I failed at Columbia, I gave them the acetate back, and I got the impression they were disappointed that Columbia didn't bite. I don't really know what they did after that. I don't know whether they immediately to marched to MGM/Verve, or if that was third down the list, or if it had to do with Tom Wilson [being at Verve/MGM].

I remember giving the acetate back--I believe I gave it back to Morrissey, I don't think I actually gave it back to Warhol, but one or the other. But I do not specifically remember retrieving the tape from Columbia's engineering vaults. This would have been the mono mix from which the acetate was cut.

Q: Although three of the tracks on the banana album ["Heroin," "Venus in Furs," and "I'm Waiting for the Man"] were re-recorded at MGM later, and one song ["Sunday Morning"] was done at MGM later in 1966 with Tom Wilson producing, it seems like all the other tracks on the LP were actually taken from recordings made at the Scepter Studios sessions where you were present. There seems to have been some remixing done, but otherwise the versions on the acetates sound like the same one used on the official album.

It sounded to me just like what we did. It didn't sound appreciably different from what we did at Scepter, when I heard it after it came out a year later.

Q: Did you ever have any contact with the Velvet Underground again after the sessions?

No. I did with Warhol, but not with the musicians, no.

Q: Looking back, how historic an occasion do you think it was to be involved with? I don't think anybody on our side of the glass had any idea at the time that was a seminal recording. I have thought about it much more in the last five or ten years than I ever did in the first five or ten years after it was done, you know what I mean? That you were being there when history was being made.

I've always been an art collector, and have a pretty good eye for paintings. And I know when you see something breathtakingly new that you've never seen before, you say, that's a damned good sign. And I would clearly come to that conclusion about listening to the Velvet Underground and seeing them perform. You'd say, this is breathtakingly new, I've never seen anything like this before. But it was much more an assault on popular taste. It's more like Basquiat or somebody like that, whose work is new and revolutionary, but not particularly lookable at first. You have to kind of buy into it. So it was a tough to get a hold of back then. I mean, obviously I think if Columbia knew what they were getting into, they wouldn't have passed, or Atlantic or Elektra either.

When I saw the Rolling Stone list of the top 500 rock albums of all time, and it was like #13 I think, it brought a tear to my eye to think of the number of records that I revere that it's considered better than.

And see our Maureen Tucker interview