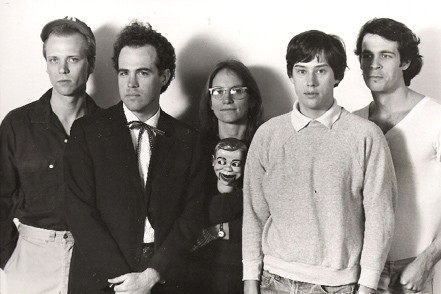

SWIMMING POOL Q'S

circa 1979. Photo by Richard Perez (circa 1979). L to R: Robert Schmid (drums); Jeff Calder (vocals & rhythm guitar); Anne Richmond Boston (vocals & keyboards); Billy Jones (bass); Bob Elsey (lead guitar). The ventriloquist's dummy head is Roy Rat Bait.

Interview by Jack Partain

(February 2012)

Though not the most celebrated band to emerge from the early New Wave scene in Athens and Atlanta, GA, the Swimming Pool Q's were undoubtedly one of the most interesting and, in a way, may have represented the heart and soul of the scene. Quirky and intelligent, irreverent and pioneering, the band, which was formed in Atlanta in 1978 by guitarist/vocalist Jeff Calder and guitarist Bob Elsey, emerged from a long history of underground rock music in the south, which was a more vibrant scene that one would imagine. After serving as the go-to opener for most of the major players touring through the south in the late 1970s and early 1980s (The Police, Devo, The B-52's), The Q's would go on to release four albums and an EP of witty, masterful power pop for the legendary DB Records, and later A&M Records and Capitol Records, before disappearing in the early 1990s. The band would suddenly re-emerge in 2003 with the release of the ambitious Royal Academy of Reality on Bar/None. I talked with Jeff Calder via email and phone in December 2011 about the past and future of the band.

PSF: You were an early fan of the Hampton Grease Band, and a friend and collaborator of Glenn Phillips. So, I'm going to play devil's advocate here (or maybe be entirely honest) - I don't "get" the Hampton Grease Band. Can you explain it to me?

Jeff Calder: A good question, which has been a great delight to members of the Hampton Grease Band, with whom I shared it. They couldn't explain it either. It may be a case of 'you probably had to be there,' to have seen the group live for them to have enduring appeal.

Until I moved to Georgia in 1978, I didn't know anyone who knew about the Hampton Grease Band. They were a phenomenon mostly localized to Atlanta despite having a double-album on Columbia Records, Music to Eat.

Rather than try to sell you on the group, I'll explain it in more personal terms. I saw them in May 1970, in Macon, a year before their album was released. They were very funny, even if you never knew what the joke was, which was most of the time. The songs were mysterious and while it was hard to have a grip on the subject matter until their album was released, one thing was immediately clear: they had a lot of words, which was important to me. Already, their presentation was taken up with long elaborations, which had for subject matter obscure Atlanta neighborhoods- strange characters ("Evans"), a detailed tourist brochure ("Halifax"), and perhaps an alien visitation ("Six"). There were no romantic allusions in their music. Everything suggested model railroading, battle stations and X-15s. They were beyond what would have been considered 'radical' at the time.

There was no precedent for a band like this to have come from my part of the world, not even the Royal Guardsmen. While the music of the Allman Brothers was comforting to the psychedelic crowd--which is not to say that it didn't offer challenges--the Hampton Grease Band was more confrontational. They didn't give a fig what the audience, hip or square, thought; they made listeners uneasy. Long hair was just starting to catch on in the South, but the singer for the Hampton Grease Band had a shaved head.

One of the things that I appreciated about the Hampton Grease Band was their maximum determination to proceed, the 'can do' spirit. The music still sounds weird, but they were against dope. They were very good players too- the interplay of the two guitarists extraordinary. The band may have split in 1973, but over the arc of the mid-Seventies, they seemed like a good model if you wanted do something against the grain of the dominant tendency (Southern Rock) which was all about fussin' and fightin' and being 'done wrong' at every turn. Like Captain Beefheart and The Magic Band, The Hampton Grease Band anticipated aspects of New Wave, Punk, Post-Punk, etc. by many years. For me, you can hear echoes in Pere Ubu and Television. I was the reissue coordinator for Music to Eat in 1996 and had to transcribe and sing all of the lyrics at a reunion show in 2004, so I probably know more about this subject than should be considered healthy.

PSF: How did he Swimming Pool Q's form and, of course, where did the name come from?

JC: I was a freelance rock journalist living in Florida in the mid-Seventies, covering the regional beat, so to speak. This was before there was anything called New Wave & Punk as we came to know it. During a visit to Atlanta in 1974, I met members of the Hampton Grease Band and became friendly with one of their guitarists, Glenn Phillips. He had just released his first solo album, which, in the modern sense, was an early do-it-yourself 'indie' album, then getting attention, in particular from Virgin Records in the UK.

Over the next four years we collaborated on a few songs together. Glenn knew that I wanted to start an original band as a vehicle for my songwriting and on a trip I made to Atlanta in 1977, he introduced me to Bob Elsey. Bob was 19, the youngest in a line of great lead guitarists that the Atlanta creative music scene had begun to produce, starting in the late 1960's. In Florida in January 1978, Bob and I worked on demos of songs, some of which later appeared on The Deep End. I moved to Atlanta in March 1978, and we began looking for members, which we located in the city's underground music world of the time. Among them was the drummer Robert Schmid, who had recently been ejected from Cruis-o-Matic, the band that had opened The Sex Pistols' American debut in Atlanta a few months before.

We were already calling ourselves The Swimming Pool Q's by June, when we played our first date at an Atlanta art collective event called The Underwear Invitiational. As a name, I'm willing to concede it may have been an improvement over the one I'd attached to my earlier Florida group, The Fruit Jockeys. It came from a misreading of "swinging pool cues" that appeared in a bar fight scene in a Mickey Spillaine novel, probably I, The Jury.

PSF: Was it difficult for the band to get gigs in the early days?

JC: Kind of, but we were lucky in that the whole New Wave thing was beginning to emerge and there weren't that many bands in the area. By 1980, there were but there really weren't that many in the beginning so we would be called upon to open bigger shows for national acts - whether we were ready to do that or not! Like Devo in December 1978, we opened for them and that was a big show for us at the time- we'd only been together playing for about six months. That worked in our favor and we were able to get that kind of exposure in front of big audiences really helped us develop as players and as a group.

At the same time, Atlanta had a long history of an underground music scene. To me, it was the only city in the South that had that and it went back into the 1960's when there were a lot of places that you could play. Rosa's Cantina, which later became the 688 Club, which was a flagship new wave, punk, post-punk club in the South. We were able to play there a few times along with other small venues. We played with The B-52's in November 1978 in Athens and by that time, we had a little bit of a resume, and a few phone numbers that Kate Pierson of The B-52's gave me, and we were able to take the band into the North East in February of 1979. We were able to get out of the South and play in Philadelphia, Boston and New York City several times and started to get our footing. We played with The Contortions, Klaus Nomi, we played at Max's Kansas City, CBGB. We were very industrious and we wanted to get out and play everywhere we could.

So when we returned to the South at the end of that tour, we were able to book ourselves into areas in the region where there weren't really new wave or punk scenes, where they had specialized clubs.

PSF: What were those early tours through the South like?

JC: When I graduated from the University of Florida I became a freelance writer and I had to try and get my foot in the door there, so I had certain skills that most musicians didn't really feel comfortable with. But that didn't bother me, it was actually kind of fun for me. So I was in a position where I could book the band myself and get us out there playing in a way that a lot of our contemporaries here couldn't. So with the resume that we had by March 1979, I was able to get the band playing all over the region in clubs that weren't what you'd think would be hospitable to a band like us. We would go into places in South Carolina and Florida and just do it. I was really like the new wave guy in the band that couldn't play very well, but every body else in the band could really play. We were kind of fearless and the South was still a region that was dominated by the whole Southern Rock ethos so we found ourselves in a lot of those situations and sometimes there was something unpleasant that would happen but we were fairly determined...

Most of our colleagues here didn't really see the value in that. Bands from Athens and so forth perceived the region as being inhospitable and very hostile to what they were doing. And they might have been right! To them, it was like, 'Well, we're going to go to New York and play.' But they didn't see any value in playing Tampa, Florida or Columbia, South Carolina. But we weren't afriad to do that and we benefitted from that because it took us a while to figure out what we were doing musically. Whereas if you take a group like Pylon, the way they were from the very beginning was pretty much the way they were. But we had a much more developmental incubation. It's just hard to get all of the complicated things we were trying to do in focus.

PSF: Is there a difference between and Athens band and an Atlanta band?

JC: I've always said that Atlanta was a music community and Athens was more of a true music scene in that there was something of a shared philosophy. It was a college town where everybody knew everybody - it was like a neighborhood music scene. And Atlanta was a big city, it could sustain a band like us and there wasn't another group like us. And there wasn't another band like The Brains. There wasn't that continuity like there was in Athens.

PSF: But the Q's were an Atlanta band, right?

JC: Yes, that's right. When I moved here I was able to insert myself into what I thought was a pre-existing music scene. Where I had been living in Florida, there really weren't any musicians who wanted to do what I wanted to do. I couldn't put a band together but I was connected here in Atlanta with the Hampton Grease Band in particular with Glenn Phillips and I was able to insert myself into the music scene. And I was able to start a band in what seemed like a very vibrant community. There really wasn't much of an Athens scene at that time but Atlanta was a place where national acts that didn't have much of a following elsewhere could come and play - Talking Heads, Elvis Costello, The Ramones. It wasn't the biggest music scene in the world, but there was a tradition of acceptance for originality in popular music.

PSF: What sort of interaction with other bands in the scene did you have? Any interesting stories?

JC: It was a really colorful, exciting, energized period in which to be involved. In the years since, I've come to believe that just doesn't happen that often. We played with nearly all of the bands from Atlanta and Athens at some point and there was a fair degree of solidarity here at that time. There were these sort of undertones of conflict between Atlanta and Athens that seem fairly petty in the distance of thirty years.

PSF: What was the most fun gig you played in Athens?

JC: We played a show with Love Tractor and The Side Effects - that was a really good show. There were like 1000 people there. When we opened for the B-52's, that was a good show but I don't think we were the right band to open that show because I think that the people in Athens wanted somebody from Athens to be the opening act, so there was a little bit of tension there.

PSF: Which band was your favorite to play with from the Atlanta / Athens area? Which was your favorite national band to play with / open for?

JC: From Atlanta/Athens, probably Pylon. Artistically, they were very different from The Q's, but we really hit it off. I helped coordinate the release of their recent reissues of Gyrate and Chomp, albums I recommend highly.

Nationally, The Police and Lou Reed. The Police were a rollicking sort- smart, funny and casual, nothing like their latter day depiction as Battling Bickersons. Their soundcheck at the Atlanta Agora in May 1978, a long elaborate improvisation, was one of the best rock concerts I've ever seen.

On the national tour we did with Lou Reed, he was very professional and supportive, always insisting we get a instrument check, for instance. Lou wanted to take us to Europe, but the label wouldn't spring for it.

PSF: Was it a bigger deal for The Q's to get a deal with DB Records or A&M records?

JC: We drifted into our record 'deal' with Danny Beard of DB- 'deal' being a too formal description since most of Danny's business relationships were based on a handshake. He was a friend who believed in the band, liked the music, and appreciated our work ethic. He had known us for a while, having been present when we opened for The B-52's in November 1978. He understood that we had, on occasion, a problematic relationship to the local/regional New Wave world. He was a free-thinker who disregarded the opinions of those who thought The Q's were too punk or not punk enough, too elitist or not New York enough. All we needed to close the deal with Danny was just to be ourselves. Plus, we were in the neighborhood.

A&M was another story. Getting a major label record deal in the pre-digital era was a fuck-ton of physical labor. Since I was the group's manager, that meant organizing demo sessions, submitting cassettes, making hundreds of expensive phone calls (when there was still such a thing as 'long distance') followed by flights to New York and Hollywood, all with no money, to meet people who only knew the band from a little tape and a handful of hip press clips. If you were lucky, you had a friend or supporter in one of the 'college promotion' departments, then emerging in the business, who put in a good word.

Most A&R reps weren't terribly impressed with regional stature; to them, critical approval was, if not a joke, little more than a nuisance. For the major U.S. labels, it was simply a question of the big picture, i.e. having a song or songs robust enough to move a large number of units to a population of 200 million spread over a vast landscape. How to do this? MTV wasn't insignificant, but it was Big Radio airplay that sold records in 1980's, just as it had for decades. The label could confront the inadequacies of a band's image at some later time, and the artists could deal with contradictions and conflicts as they came along.

This whole line of pursuit -- securing a 'real' record deal -- was a high stakes operation. It was far more involved than gaining the approval of underground publications or begging the largesse of small town potentates. To the extent that any of today's young indie bands might be interested in a major record deal, I'm sure some of the preceding still holds true. Of course, their managers would no longer need pockets full of quarters.

Finally, it meant training a band's attention on things other than performing, working up new material, and avoiding the consequences of misadventure; as anyone who has ever tried to do this can tell you, this part of process is a huge pain in the ass. For example, try putting together an expensive photo session involving five musicians. Other than a general course of action, there wasn't much of a playbook, at least in our part of the world. As my friend Terry MacGovern used to say, you jump first and figure it out on the way down. So, yes, on a sheer scale of concentrated endeavor, a deal with A&M Records was a 'bigger deal,' the prospect of enhanced recording budgets aside. The Swimming Pool Q's were fortunate in that we came to the attention of David Anderle, a major force inside the A&R Department of A&M Records.

PSF: Can you describe your experience with A&M Records?

JC: The first year that we were there was really good and the second year wasn't so good. And I don't think the reasons for that had a whole lot to do with the band, they just had to do with politics at the label and the people that were there. A&M was a Los Angeles based label and that was a long way from Atlanta. So ultimately, we were kind of remote for them.

A&M was a label that was a major label that wanted to be an independent and an independent that wanted to be a major and they were very successful. They were located on this old Charlie Chaplin film lot. It wasn't a high rise, it was an old film lot so all the offices were in the little bungalows and it was very different from my experiences over the prior five years visiting labels in New York and L.A.. They took a liking to us initially and we played a show at the Greek Theater and the whole label came down and they sent us on a national tour with Lou Reed. And amazingly, they let us do a second record because the first record was like right at where the number should be where they would decide weather or not to pick up your option. But by the time that Blue Tomorrow was released (1986), we had become somewhat remote for them. Even though I think the record turned out very well and was unique, and had things that they could have promoted that would have broken us to a wider audience, the relationship had become strained. But that seems to be the normal experience with record companies. I think it's quite different for bands now.

PSF: What's going on with the cover of Blue Tomorrow?

JC: We were shooting the cover for our album in Sarasota, FL with the Ringling Circus. The small horses were present on a circus preserve, and, as an afterthought, we posed for a picture with them. It was never intended to be the cover, but, as sometimes happens, we lost control of the album artwork. To answer more exactly, there's not a whole lot 'going on' on the cover: the horses display more animation than the band. The colors have some real vibrancy. Anne's footwear has a little show.

PSF: In a recent interview, you described the Swimming Pool Q's as more "conceptually complex" than other bands in Athens/Atlanta at the time. What do you mean by that? Also, do you think it was a conscious decision for the band to move in that direction or just a natural sort of progression?

JC: By more 'conceptually complex,' I didn't mean smarter, just more organizationally involved and pursuing a greater diversity of subject matter. I have to say that I'm not completely comfortable simplifying my response here, but... Most of our contemporaries in the Atlanta/Athens music scene of the late '70's/early '80's had a singular focus: a lead singer supported by a simple trio of bass, drums, and guitar. At least in the beginning, their compact lineups governed, and were governed by, the 'minimalist' aesthetic that was then a strong tendency in the Western World of New Wave & Punk, a tendency echoed throughout the Southern enclaves of Atlanta and Athens. The minimal approach, while certainly less expensive, wasn't really The Swimming Pool Q's personality.

The B-52's, with their three voices, are an obvious exception to the above, but they defined themselves-made themselves coherent-via "Dance Rock," a genre which, as far as I can tell, they invented.

By contrast, The Swimming Pool Q's were/are endlessly involved. We had two very different lead singers, although each of us wore horn-rimmed glasses: (1) a male untutored monotone, originally blues in orientation; generally rogue-ish, (2) female, folk-like and skillfully melodic with an advanced idea of choral harmony; mostly strict. Lyrically, some songs had a surreal or satiric sense of humor; others had aspects of romance, tragedy and melodrama. They have always been wordy. One of the two guitar players was clean and rhythmically stiff; the other (Bob Elsey), more gifted, used distortion and played fluid solos. Overall, the musicians demonstrated traditional capabilities at odds with the don't-let-on-that-you-can-play-your-instrument crowd. Taken as a whole, our approach may not have been the best promotional strategy, but, to be sure, it was more conceptually complex. I've never thought there was anything about The Q's complications that made us superior to our Georgia peers. It's always been something to fret about and never easy to pitch. Please believe me.

PSF: In the late '80's or early '90's the band seemed to either break up or go on an extended hiatus? Can you clarify this?

JC: Well, you know, we didn't really do either one of those things. We released an EP in '87 on DB and World War Two Point Five in 1989 and then it took a couple of years for me to figure out what I wanted to do next as a songwriter and what the band wanted to do next. But we were still active during that whole period. We continued to play a bit regionally throughout the early '90's and then I began to work on Royal Academy of Reality and that took many, many years to produce. It was really done by the late '90's but it took another five years to get it released by Bar/None.

It may have seemed like we weren't that active but I was thoroughly involved in trying to make that record a reality. We were active in a different way.

PSF: Royal Academy of Reality is quite an ambitious record. Where did it come from?

JC: If two more albums hadn't come out between Blue Tomorrow and Royal Academy, I don't know if it would have seemed so jarring of a transition. Blue Tomorrow was a pretty sophisticated record. We made it with producer Mike Howlett who worked with A Flock of Seagulls and Joan Armatrading and we were able to make a 48-track analog album which was, for the people from our world (like the bands we were a part of), that was really unprecedented. We really pushed the production to a whole new level. And because of that experience with Mike Howlett, we had ideas about more sophisticated record making. So with Royal Academy, there was really a precedent there with Blue Tomorrow. And by the early '90's, I wanted to make an album that was more of an album and not just a representation of what we were doing live. And with the precedent of Blue Tomorrow, I kind of knew how to do it, even though we didn't have any money!

With our first A&M record, we were trying to make an album that had guitar orchesrations that were elaborate. And with Blue Tomorrow, we went to whatever the next step would be- something like Roxy Music's Avalon but with guitars. Which was not easy to do, and I don't know if a whole lot of people understood. But we were lucky that Mike Howlett did because it could have gone the other way, especially given the world that we came from- the new wave and punk world where bands like us would have a lot of suspicion and paranoia about being manipulated and we had to get beyond that to make these records. And I think that being exposed to the bigger picture of the American scene really helped.

PSF: In a recent interview, you said "I guess I just didn't know enough about the music business to discourage me. In the years since then, I've had a lot of extreme and diverse experiences in the music business – if I had known then the things I know now, I don't really know whether I would've done this or not." I guess my question would be, was your experience in the music industry largely positive or negative?

JC: Largely positive, although it's strange to say it. I love the lying. The betrayals are meaningless. People aren't really trying to hurt you; you just pop up on their radar for a minute, then they're off to the next important thing. The whole enterprise isn't worthy of your anger. The biggest stars in the business end up getting boned too, so you're usually in pretty fair company. Honestly, many of my closest friends today are people I've met in the industry or on the scene over the last 30 years. The most negative thing about the music business is that it steals attention away from the time you have being creative. The rest of it is just good stories.

PSF: What has the band been up to in the last few years?

JC: The band is the same lineup as in 1982 except for our bass player, who is our original drummer, Robert Schmid. We were having a dificult time stabalizing our bass position and really couldn't find any one willing to put in the time to be in the band. So Robert said 'Well let me play bass.' And we said 'Well, you can't play bass.' And he said 'Well, let me just try it.' And amazingly, he's done a really good job of learning the material and learning to play the instrument. We've been playing over the course of the last year a lot of dates and he sounds great.

We play songs from all the way back to the beginning of the group. I think most bands get tired of playing their early stuff but it's still pretty enjoyable for us. Some of the things from Royal Academy are kind of hard to pull off... but we've done it! The band has been playing together for so long that it's a really good sounding band. When we get on stage, we've been doing this so long everything just falls into place. Even if the rehearsals seem terrible!

I've been able to complete and mix about seven new songs. It helps that I've been an associate producer at one of the nicest recording studios in the world (Southern Tracks) and I occasionally have access to their facilities.

At the same time we've been trying for years to get our A&M records reissued and that's been a real saga, especially in an unstable time in the music business. But we are the closest we've ever been to getting those records released and starting in January, we're going to start raising funds to do that. I've remastered the records with bonus tracks. I want it to be a nice package with extensive liner notes and photographs from our archives.