SUICIDE

|

|

The Second Album sessions

Book excerpt by Kris Needs

(February 2016)

"The first and second Suicide albums are at two extremes to each other," understates Marty Rev. After the live DIY innovations of the debut album, everything about the album which became Suicide: Alan Vega and Martin Rev was different and new; including its record label, producer, the state-of-the-art equipment it was realised on and the studio it was recorded in, which was one of the most expensive in New York City. Suicide knew they had been given a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, so grabbed it and made the album which many consider to be the real peak of their career.

ZE Records boss Michael Zilkha loved Suicide and fantasised about hearing them produced by Giorgio Moroder, with Rev steering the cut-glass sequencer glides of "I Feel Love" under Vega's quivering Elvis croon and volcanic yelps. Zilkha saw this as an audacious future sound which could legitimise disco and captivate the crossover crowds he was targeting with ZE. But Ric Ocasek had already taken Alan and Marty under his wing and into the studio to produce the masterful "Dream Baby Dream." Their staunch sense of loyalty plus the potential of this new relationship meant it could only be Ric's arse sitting in the producer's chair when the time came to record the next album. Instead, Zilkha contented himself by presenting Ric with a copy of "I Feel Love" as a template. "That was Michael's life," says Marty. "He led that life. He wanted us to be successful and cross over into that. He was bright enough to know there was something there in Suicide, even though it wasnít his personalised sound."

Since first embracing disco as the latest manifestation of the spirit and struggles which had drawn him to R&B, jazz and conscious soul, Marty had been keeping up with the electronic innovations running riot in the music during the late '70ís. "I couldn't help absorbing it," he says. "By the end of 1979, a lot of things had happened. Punk had established itself internationally, and we had had the first record out and toured Europe. Then you had the intonations of new things being used in electronics, which had started with Donna Summer and Giorgio Moroder producing disco in Europe. Disco had a big effect and even more technology was now being used. You could now feel disco coming out of the neighbourhoods very strongly. With me, it went in, so a lot of it was subconscious, and a lot of it was conscious. 'Oh man, I can drop that in without doing it in an obvious way.' Anybody in the 70s was attaching on to this thread. It was the fashion. I wasnít interested in doing it that way, but if I heard a riff that I liked, or a rhythmic feeling, I could bring it into what I was doing."

Apart from disco's social resonance, Marty was drawn to its technological innovations, which could super-enhance the beat to outer space or the bedroom while taking its sonic textures to the heavens. "Technology had somewhat flipped out since two years before," says Rev. "All of a sudden there was the Prophet-5 synth and these drum machines. Disco came out with this kind of hi-tech, lo-tech rhythm section, which kind of paralleled and had some sympathy to what I was doing. I felt aligned to it, to a certain extent. I got ideas from it. A lot of good, catchy stuff came out of the disco world and I was listening to it all. There were a lot of 45s I picked up on. I know that had an effect on what I was doing, for sure."

Ocasek was something of a tech-boffin himself, as shown at the "Dream Baby Dream" session when he ordered in the brand new Roland C-78 drum machine. To provide further state-of-the-art kit to record his dream disco album, Zilkha gave Suicide a 10,000 dollar equipment budget, which was more money than they had seen in their lives.

"We got all this money," says Alan Vega. "It wasnít a ton of money, but it was a lot of money for us. For us it was like Rockefeller! It was fucking amazing. Ten grand to spend at Sam Ash, accompanied by the Cars' roadie, buying keyboards and guitars."

"We could get anything we want," adds Marty. "I was like a kid in a candy shop. Ric said to me, 'There are a lot of great instruments around, what do you want to use?' He told me what was around and showed me pictures, so I could pretty much order anything I wanted to use in the studio and then I could start using it live."

Zilkha booked Suicide into the Power Station, one of the top studios in New York. At that time, the converted Con Ed power plant on West 53rd Street was New York's most revered high-tech studio, renowned for its wooden-domed ceiling, 42-track desk and acoustics which seduced names such as Bowie, Lennon, The Clash and Aerosmith. The then-unstoppable Chic were in residence. One of my most treasured memories is the evening in 1983 when, at Nile Rodgers' invitation, I visited the Power Station and witnessed Chic at work. The studio was plush, low-lit and funky, and I couldn't help trying to imagine how Suicide must have felt the first day they walked through those hallowed portals.

At first, they must have been surprised because, sitting at the control desk on their first day was the same Larry Alexander who had fled in terror from the first album sessions. He was now in-house engineer at the Power Station. "Whoís sitting at the board but Larry Alexander!" laughs Alan. "He sees us walking in and goes, 'I quit, I gotta get out of here!í He just went crazy. But we were with Ric now, so he cooled out. But I'll never forget his expression when he saw us walk in. He freaked. He could not deal with the thought of us again."

For the album, Marty's principal analog battle weapon became the Prophet-5 synthesiser, introduced by the San Jose-based Sequential Circuits in 1978 as one of the first affordable polyphonic synths. Viewed as a major development, it would establish the classic '80ís synth sound and boasted an all-important balls-out bass sound for Rev. While Marty was still exploring the Roland CR-78 drum machine, Ric also brought in the latest Sega 78, where buttons were pushed to get a beat.

Now might have been the time for Suicide to either amp up their song aspect or further explore the experimental paths of the first album with this new technology. Instead, they made a sleek, disco-inflected New York classic, which Marty likes to describe as a "psychedelic orchestral version of Suicide," which he says was backed up by a musicologist friend describing it as "the Sergeant Pepper's of electronics." Ultimately for Rev, the album was another phase in the ongoing journey which, a few years earlier, had seen him hammering colossal noise emissions out of a cheap, hot-wired organ.

This time, the recording process saw the live takes of the debut album replaced by meticulous overdubs. While Alan concentrated on honing and singing his words, Marty set to work like a scientist. He doesn't even see the album as representative of Suicide at that moment; more a high-tech detour. In retrospect, it was a perfect move. If the first album had set new benchmarks for sonic extremes and tapping into the dark side, Suicide now started their new decade by presenting a way of working with electronics which uncannily presaged things to come, from synth-pop to acid house.

"The second album was all recorded separately," says Marty. "Ric said 'lay down tracks,' so I would record part after part. It was all very fresh to me. I had the Prophet-5 and drum machines which, at that time, were very new and worth exploring. It was a big studio. I remember Ric was very far away behind the glass in the control room! Then Alan would put his vocals on separately, then I would come back and add things to what he did and we'd go to the next one. It was like one track after another; 'let me throw all these colours.' It wasnít Alan and I really cutting it together. There were so many tracks it was kind of multi-layered, and it kind of worked for me like that. We had never approached Suicide that way. I suppose, in many ways, it was recorded like a solo record, so the tracks probably reflected that. It was really more of a studio album, whereas the first album had really been us cutting it live in half an hour!"

Marty had been given another new path to explore, which became another step in his ongoing musical quest. "The technology was always very much part and parcel of what my searching was all about. Sometimes you realise after you do something, it's not really what you want to hold on to. I guess a lot of the second album came out of the fact that we now had access to all these instruments. One of the basic ideas in my mind as the album was developing was, 'Hey, what would it sound like with an instrumental approach?í With Suicide, everythingís multi-faceted; itís like a ship in a bottle. It has its own special, fragile kind of song form from two people. It kind of works that way, but at some point itís like, 'Okay, letís try this without vocals! Letís try this with five vocals!í It just begs a lot more possibilities. On a simpler level, I was thinking, 'We havenít done that yet, what would that sound like?í So thatís a basic idea that gets you started. It was definitely out of what I was doing with Suicide but, in the working out of it, turned into something else."

Sonic exploration aside, recording at the Power Station was a memorable experience thanks to the neighbours working in the other studios, including Chic, who were producing Diana Ross's multi-platinum career-revitalising Diana. Also around was Carly Simon, and Bruce Springsteen, who had been working on his epic double-album The River since March. "Bruce was next door just a few feet away," recalls Marty. "I think he already knew of us by then. When we felt the album was pretty much done, he came into the control room one night, and listened to the whole playback. He said something to Alan, while I was sitting off to the side listening. Then he came over to me and said, 'I really like what you guys do'. He was familiar with us already, which was saying something because we'd only had the first album out."

"Bruce came in and flipped!" recalls Alan. "He liked it right away. When Bruce was there, his roadies would stay with him, because they really love the guy. I used to hang with him a lot. His manager didnít want him to be drinking or anything, but I used to keep a bottle around all the time. It was like kids in school, going to the bathroom to smoke cigarettes. Heís just a great guy." Alan also recalls "Carly Simon heard Suicide and gave this disgusted look. No one wanted to be around her, man, although Diana Ross was friendly."

After Ric brainstormed the selection and running order, Suicide's second album was ready. It was called Suicide: Alan Vega and Martin Rev. The cover, which Marty reckons has "a disco feel," features a blood-splattered bathroom. But, instead of propelling Suicide to their deserved global stardom, the record would actually herald a barren stretch and the world wouldnít see another album from the duo for eight years.

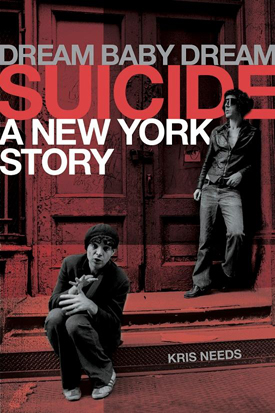

The author and Alan Vega