Salsa in the 70's

Birthed by Tommy?

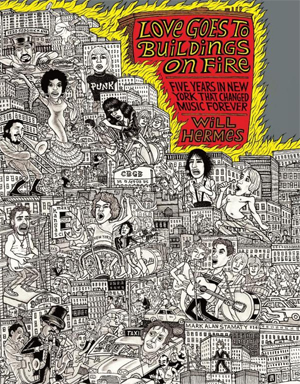

Book excerpt by Will Hermes

(December 2011)

ED NOTE: Hermes is known as a writer, editor and educator, presently working for the likes of The New York Times, NPR and Rolling Stone, not to mention former stints at City Pages and Spin, among other places. His new book draws a musical picture of New York City in the early and mid-70's, covering everything from rock to jazz to punk to classical to disco in detail and through dozens of interviews with the movers and shakers who were there. One particularly interesting facet that he uncovers is the evolution of salsa music into the mainstream, courtesy of a sort of tribute album to a certain famous rock opera.

Excerpted from LOVE GOES TO BUILDINGS ON FIRE: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever by Will Hermes, published in November 2011 by Faber and Faber, Inc., an affiliate of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright (c) 2011 by Will Hermes. All rights reserved.

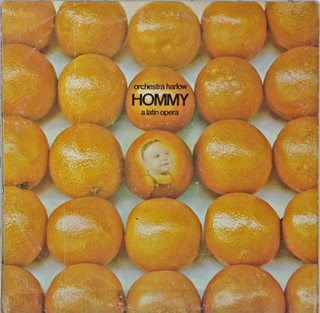

It makes an odd kind of sense that the event to announce New York salsa's coming-of-age, and to reboot the career of Latin music's greatest living singer, would be a salsa remake of the Who's Tommy staged at Carnegie Hall.

The "rock opera" Pete Townshend had written a few years earlier represented more than his need to be perceived as an Artist in the wake of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Heart Club Band; it was a landmark of prog rock's hypervirtuosic, movin'-on- up sensibility of the early- to mid-'70s. Similarly, salsa wanted to travel beyond the barrio--to be seen, and to see itself, as more than just a ghetto dance-hall soundtrack. It was virtuoso music with deep history and an international pedigree; it wanted respect.

Appropriate to salsa's melting-pot culture, Hommy, a Latin Opera was cooked up by the flamboyant composer- bandleader Lawrence Ira Kahn, a.k.a. Larry Harlow. Kahn grew up in Brooklyn, the Jewish son of the opera singer Rose Sherman and Buddy Kahn, who worked for a while as bandleader at the Latin Quarter in Times Square under the stage name Buddy Harlowe. By the time he was a student at the High School of Music and Art up on West 135th Street in the '50s, Larry was obsessed with Latin music. He would head back to Manhattan on Sunday afternoons to see incredible bands at the Palladium Ballroom, the second- floor dance club on Fifty-third and Broadway--Arsenio Rodriguez, Machito, Tito Puente. Harlow was underage, but the owner, Max Hyman, a kindred Jewish mambo fan, would let him in anyway. In his late teens, Harlow went to Havana to study Cuban music. But the revolution soon forced him back to New York, where he followed in his father's footsteps--first playing Latin music, and, for a while, leading a Blood, Sweat & Tears-style rock band, Ambergris.

The storyline of Hommy was written by Genaro "Heny" Alvare, a Puerto Rican singer, drummer, and songwriter who worked days as a jewelry polisher in the Diamond District on West Forty-seventh Street.

It involved a blind and deaf boy with a talent not for pinball but for-- what else?--Latin percussion. The music bore no resemblance to the Who's original; this was Cuban son and guaguanco spiced with jazz charts and other flavors. And who better to sing the production's signature number, thought Harlow, than Celia Cruz?

Cruz had been living in the New York area since declaring herself a political exile from her native Cuba in "62. But the music she'd been making in Havana as a singer with the great Sonora Matancera, and in New York with Tito Puente and others, had fallen out of fashion, overshadowed by Latin soul and boogaloo, as well as rock and the nascent pan-Latin salsa sound. At this point, she spent seven months of every year living and performing in Mexico.

Harlow met Cruz in Mexico and told her about his project. When Cruz returned to New York, she scheduled her first meeting with Jerry Masucci, cofounder (with the bandleader Johnny Pacheco) and business end of New York"s preeminent Latin label, Fania. Cruz had come merely to talk. But it was a setup: when she arrived, she found a studio full of musicians ready to record. The song was Hommy's equivalent of Tommy's "Acid Queen," the kinetic "Gracia Divina." Cruz had never heard it before.

"I got so angry," she recounted in her memoir, "and I'm not an angry person." But the gracious and professional Cruz learned it and sang it. Over a swirling, elegant charanga- style groove with full strings and gleaming brass, her bittersweet chocolate alto sound is unassailably regal. It's hard to know whether to dance or simply bow down.

Knocked off in a day, "Gracia Divina" became a massive hit on New York Latin radio: on Polito Vega's Spanish-language afternoon show on WBNQ 1380, Joe Gaines's late-night *n glish-language show on WEVD 1330, Felipe Luciano's Sunday specialty show on the jazz-minded WRVR 106.7. On March 29, Cruz sang "Gracia Divina" for a packed house in Carnegie Hall at Hommy's world premiere, backed by the Orquesta Harlow and alongside the deep-voiced Cheo Feliciano, who had recently returned to claim his throne as the king of New York salsa singers after kicking a heroin addiction. The record flew out of the racks; the opera was produced in Puerto Rico and elsewhere.

But Hommy's greatest effect was validating a group of young musicians, proving their music was worthy of Latin music's queen, and of one of the world's great concert halls. And performancewise, Harlow and the Fania crew would pull off something even more amazing by the end of the summer.

Latin music had been an integral part of New York's musical fabric for

decades. Always part of the jazz's scene, there were periods when the

music's cultural presence ballooned. There was the mambo craze, which

took off in the mid-'40s at the Palladium Ballroom. In the late '60s,

there was the boogaloo era, in which Latin acts responded to R&B's

golden era with their own hybrid soul music. Boogaloo was hated by

Latin music purists, but it was perfect New York street pop, all simple,

irresistible rhythmic and lyrical come-ons. (One critic dubbed it "cha

cha with a backbeat.") Joe Cuba's "Bang Bang," Johnny Colon's "Boogaloo

Blues," Ray Barretto's "El Watusi," and Pete Rodriguez's "I Like It Like

That" are songs smart DJs still drop into dance mixes, and they always

rock a party.

The "salsa" of the early '70s was not only more traditional than boogaloo, it was hotter, faster, brighter. It was not mellow, and it was not as refined as its Cuban models. Heard as a compressed radio signal blasting from shops, apartment windows, and passing cars, it sounded brassy and shrill--fun, hustling, terminally high-strung.

New York salsa was fusion music; you could hear urbane Havana son and country Puerto Rican jibaro styles, jazzy horn and flute solos, Santana- style rock guitar, wah-wah keyboards, long percussion jams that drew on funk and African music while mixing in various Caribbean and South American rhythms. It was integrated, like the city it came from.

To wit: on May 3 at the Lowe's Paradise--the spectacular old Bronx theater at 2413 Grand Concourse--a triple bill featured the formal debut of Tipica '73, the salsa group that had just splintered from the conguero Ray Barretto's band. With them was the Jersey City R&B crew Kool and the Gang, who were working on an album that would include a song called "Jungle Boogie." Rounding it out were the "60s pop-rockers Tommy James and the Shondells, whose '69 hit "Crystal Blue Persuasion" was a hit among Bronx soul fans, Latinos included; Joe Bataan and Tito Puente both covered it.

It was an unusually mixed bill, given the tendency of music marketers to divide audiences along cultural lines. But salsa, R&B, and rock have a central thing in common: they worship rhythm. If it makes people move, it's all good. Not far from the Grand Concourse, a group of smart young DJs were learning this.