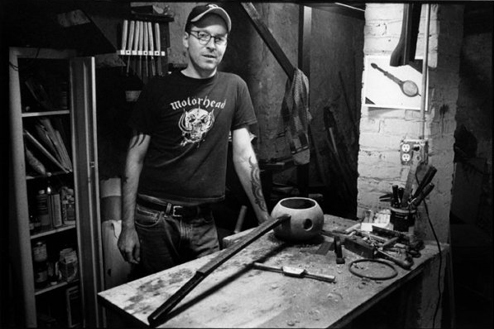

Pete Ross

Photo by Cynthia Connolly

Baltimore Punk & Banjo Maker

by Kevin Chesser

(June 2012)

Around a couple of narrow corners and up a shady one-way street, my friend Pete Ross lives and works out of his Baltimore City row-house. And if you go there, you'll notice that it's not the living room, kitchen, or the two upstairs rooms that are the most functional or most well-used spaces there. The guy essentially has zero furniture save for a couple of camping chairs, a coffee table, and his bed. To see the true functionality of Pete's place, one must step into the basement, the workshop of Jubilee Gourd Banjos, Pete's business.

Gourd banjos, in case the name did not give it away, are primitive instruments with bodies made from dried gourds, an animal hide stretched over the body, and a wooden neck attached. Pete's particular specialty is the construction of such instruments with close attention paid to the historical resemblance (if not complete replication) of what would have been played by African slaves on early American plantations.

Pete has built banjos for more folks than can be listed here, but of particular note is legendary old-time musician and folklorist Mike Seeger, as well as West African musicians Cheick Hamala Diabate and Barou Sall. Along with serving as an artistic and historical consultant, Pete also built a gourd banjo that was featured in the PBS documentary Slavery and the Making of America. His instruments have been commissioned for countless exhibits, including the Museum of Musical Instruments in Brussels, Belgium and the Blue Ridge Institute in Virginia, and he has lectured on the history of the banjo at Appalachian State University and the Baltimore Civil War Museum.

But when I am over at Pete's house drinking gin, beer, and bullshitting on a frigid January evening, he enthusiastically plays the Screamers, Blitz, and GG Allin in one YouTube search after another.

And at first glance of Pete, the first thing that springs to mind may not necessarily be banjos. Between the tattoos, skinny Dickies, and Chuck Taylors, Pete has the look and attitude of an old-school punk rocker, which he is. Currently, he plays bass in a punk band called Adults, the latest of many Baltimore and DC area groups he's been a part of since his youth.

Punk rock and old-time/banjo music are, in a general way, not typically associated with one another. Punk has always been vehemently left-wing, anarchistic, and nihilistic, and generally known for representing the frustrated cry of out-casted dwellers of cities and suburbs. Banjos, while originating in the hands of African slaves, America's original disenfranchised ethnic/social group (aside from Native Americans, obviously) have come to be widely associated with Pete Seeger style cheese-alongs and as an outdated icon for the backwards ways of the historically conservative American south.

But Pete, like many others with a vested interest in the history of the instrument, doesn't see it that way. For him, the banjo is deeply tied in with a populist and D.I.Y culture. Pete's first true ‘light-bulb' moment of being captivated by old-time music came during a busy day while working the register at a Washington DC area record store:

"One day, it was really crowded in the store, with a huge line, and the CD playing came to an end. So I went over to the blues section, looking for something to put on that was inoffensive, maybe interesting, so I just grabbed one randomly and threw it in there. So, I'm working the line, ringing people up, sending them on their way, and about 3 songs into the CD, my ears lit up; amazing stuff, this really rough and ready, minimal, acoustic music, and so I finished up the line, went to see what it was, and it was Altamont, the Black Stringbands Record, field recordings from Middle Tennessee."

Rough, ready, and minimal. Sound familiar?

"From then I was possessed."

But it was not only the aural quality of the music that intrigued him; the cultural context for these Middle Tennessee old-time musicians stirred his interest as well.

"The whole thing of black guys playing banjo music was so intriguing, it conflicted with my notions of what my relationships were about between races, like, not only is there an interaction here between white people and black people, but the white people and the black people that I thought were the most decided enemies of one another."

At first, Pete's burgeoning interest the history in the raw, hypnotic, fiddle & banjo based music that had caught his ear on that fateful day led him to the libraries.

"I started reading more and more about the earliest history of the banjo, from the time in the 18th century when nobody thought of it as anything but a black instrument, and how people became fascinated with the instrument, and how that gave rise to the minstrel show, and how central it was to the formation of our popular culture. So I decided that I had to see one of these things."

But when Pete got around to visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see their so-called slave banjo, he immediately knew something was off:

"I thought: this is kinda bullshit. This is an 1840s banjo neck that somebody later came and shoved a gourd on. And I realized that there was not an existing instrument from this period."

Pete's time as a student at the School of Visual Arts in New York City also fueled his desire to bring one these old instruments into existence, as he found his own personal values drifting from those of the arts community he was involved in.

"I was disillusioned that it was so elitist, some of it really seemed to be exclusive, like to decode this art you're looking at, you needed a higher education, and it seemed that it was really by design, like, they didn't want other people to understand, in fact they wanted it to be a little alienating of the average person. It seemed like in alienating average folks, it sort of affirms their elite position in society."

So Pete began working on these Plantation-era reproduction instruments, driven not only by sheer fascination with their associated music and history, but also by his pursuit to connect with art in a way that was physical and immediate. "There's this world of guys who are sort of like me; they have a background in the arts, and even though they're still doing pure art in a sense, they want to get their hands in the nitty gritty things, so a lot of these guys have become metal-workers, so I'm going to these guys to cast parts, or to form parts for banjos, but these are guys with an arts background who want to make stuff, they want to work with their hands."

Pete generally takes two routes in the construction of his banjos: they're either reproduced from a physical artifact or based on an early artist's depiction (for instance, one instrument that Pete makes is modeled on the banjo depicted in the famous 18th century painting The Old Plantation). When doing a pure reproduction of a physical instrument, Pete reproduces the scratches and tool-marks left by its maker who has been dead and gone for 200 years. But working from a photo or painting presents its own distinct set of challenges:

"How precisely am I trying to reproduce an image which was maybe made by an unschooled artist anyway? Am I making an exact reproduction based on a child's drawing? Well, if you made an exact reproduction of an airplane based on a child's drawing, it wouldn't fly for a second. So you have to balance these things with your knowledge of instruments, fill in the gaps with the written descriptions, your knowledge of African instruments, and your knowledge of the banjo since then, and you have to make your choices about what's gonna work, but you still wanna be true to the history of the thing."

The need to be true to an authentic source of inspiration applies to both of Pete's main passions: punk rock, and traditional music of the banjo. Pete sees them as parallel artistic worlds: both are raw, stripped down, and completely indifferent to music theory. Both represent art not for art's sake, but art as a day to day necessity for coping with the frustrations of your immediate environment; whether that environment is marked by the faceless and half abandoned shopping malls of Prince George's County, Maryland, or the monolithic and ever-enclosing mountains of a southern West Virginia coal town.

Furthermore, both forms represent a desire to be connected with a cultural identity that is vital and sincere, channeled through art that is scraped together from little to no resources, and tells true stories in a minimalist format.

"Fuck commercial culture, fuck the identity that's forced upon us by the marketplace," Pete says.

"You turn to traditional culture because it's a way of ridding yourself of this influence that's created for the most cynical reasons, to just sell you something. I want something that's true. I want the organic identity, the organic culture, uncorrupted by marketplace. And that's one of the reasons I like the old-time music thing. That's where, for an old punk, I touch on the back-to-nature hippie thing; to just rid yourself of this world, the world of sin (laughs) or something."

Lately, Pete is playing local shows with his punk band, Adults, recording an album with them, and working on the balance between "squonky art punk" and the "hardcore stuff." And when he gets a chance, I'm going to have him show me how to play some of those old Uncle Dave Macon banjo tunes.

Two disparate realms that are not so disparate after all.

http://www.banjopete.com/index.html

www.facebook.com/adultsbandbaltimore