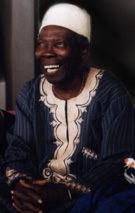

Babatunde Olatunji

Photos: Olatunji Music

Interview by Jason Gross (October 2000)

Olatunji was much more than a gifted, groundbreaking artist. By the time that his music was making the charts, he was also making the lecture circuit, going around colleges to talk about African culture. He also decided to create his own arts center to promote the work of other musicians and teach young people about music. His work schedule was punishing but Olatunji was tireless: from 1968 to 1982, he taught at Roxbury (Massachusetts) two days a week then teaching two days a week a class at Kent State and then traveling back to New York for the weekends to teach at his own school.

His quest has spanned to today and found him many musicians as supporters (and collaborators) of his work, including John Coltrane, Carlos Santana, Taj Mahal and the Grateful Dead. His latest album, Love Drum Talk (on Chesky, 1997) earned him a Grammy nomination and a new generation of admirers. I met Olatunji in April 1999 to talk about the span of his career.

Special thanks to Olatunji enthusiast Maureen 'Moe'

Tucker for her encouragement.

2003 update: Sad news as Baba passed away in California on April 6th at the age of 76 from diabetes. He will be missed and he will be remembered.

PSF: Before you came to America, when you were growing up in Nigeria, how did your interests and studies with music begin?

I grew up in a village where music was a way of life. Everyday you wake up and you may be celebrating the birth of a child, the coming of age of a young man or woman, someone taking a giant step in life (getting married) or someone passing into the spirit world. All of this is celebrated with music and chants and dance. I would say that music covers all the vicissitudes of life. So you grow up as a child seeing all of this and being part of it. There's no way of escaping it. It's just like any young man here in America will wake up at any time during the summer and can grab a baseball bat or pick up a basketball and play around with it. It's one thing to know something about it but becoming Michael Jordan is another thing.

I grew up with that and my interests grew up with

that. In retrospect, I remember very well that I was always on the side

where the musicians were instead of where the audience was at all festivals.

Every weekend there was a festival in the villages. You are just there

and you are a part of it. But for me, I would always stand where the musicians,

the drummers were. I remember that very well.

PSF: Who were some of these musicians who influenced you early on?

Master drummers, griots whose daily life involved

preserving the culture. These are really professional musicians whom you

would see at all the occasions that I mentioned.

PSF: What was it about their work that made you want to do it yourself?

I noticed that people paid them respect and gave them a tremendous amount of attention for what they did. They acknowledged their presence and really had a place for them in society. Those who wake up every day to play music, those who go to the marketplaces to perform where the women sell their wares, those are the professional musicians. Those are the historians. Those are the people who through their songs, you can really write the history of a city, about the movers and the shakers in the city or people who are legendary, people who are great, people who did good work and those who did bad also. Through the songs that they write, you can learn about people who make contributions to society. I was so fascinated by them.

There was one particular griot called Denge. He was

like one who would sing about kings and chiefs, remind them of their upbringing,

remind them of the great contributions that their ancestors gave and make

sure that they follow tradition. He was very, very cool.

PSF: This was probably before radio or television entered the picture so they were probably an equivalent form of entertainment also, right?

No radio, no TV. (There were) social events that

followed each other in succession in our daily lives. There's always a

child being born in the village. There's always someone getting married

in the next town and you hear about it and people go to it. These are events

that are announced by word of mouth.

PSF: What led you to come to the United States in the 1950's?

Luckily, by divine right, both of us (his brother also) won the Rotary Educational Scholarship in 1950. That's how we came to the United States, to go to Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia. We were overwhelmed when we came here. (laughs) Really, it wasn't what we thought it was or all of things that we read about it. We were very naïve about the social situation, the race relation situation. We went to school in the South. At our arrival at Morehouse Campus, which is a black college, we saw some people who looked like people we knew at home. They would tell us "No, we're not from Africa." I'd tell them "you look just like my cousin" and they'd say "no way!"

We went through all that whole period of trying to educate our brothers and sisters about their African heritage. That's how the whole thing started with me as a lecturer.

I was studying political science to become a diplomat.

I changed though. When I came to New York, I went to the New York University

Graduate School of Public Administration and International Relations. But

that was a period when social change was going on in the process and I

was a part of that. I was the one who was called to present African programs

for Black awareness for NAACP and other groups. There was a good response

to this. I performed at these events throughout the sixties.

PSF: What led to you getting the chance to record an album?

The way the whole situation started was that I had been in a situation where before I left Morehouse college, I had established myself in a way of letting it be known that this is a cultural basis for our unity. I did this by presenting African music and dance while at Morehouse. I wanted to create the true image of African- not Tarzan or the Hollywood image. So upon graduation, I planned to continue the same thing. When I came to New York, I started going about lecturing in schools.

In 1956, I contributed to the first UNICEF recording for children. I had a sponsor who was teaching history in Boston and we recorded it when he returned. The UN Choir was singing at a party for New Year's Eve, which I went to. I was asked to do a chant and the choir director said 'Ooh, that voice!'

I was introduced to a man at Radio City (Music Hall), Raymond White, the arranger for their Symphony Orchestra. I went there and met him and (we) collaborated- we did a 12-minute piece called "African Drum Fantasy" in 1958. That was my biggest break. Before that, I had been at schools lecturing and performing African music and dance, talking about he rich cultural heritage of Africa as related to blues, jazz, gospel singing. I was there (Radio City) for seven weeks, four shows a day with the Symphony Orchestra. It was reviewed by all the daily newspapers there of the day.

It was then that Al Han, artists representative of

Columbia Records, came to me and said 'We'll put you in the studio.' That

was the recording of Drums of Passion. It was number 13 on the Billboard

charts. It was the first African recording that really demonstrated the

impact of percussion in music.

PSF: Do you feel that there are medicinal powers in your music?

Possibly. We are now experiencing and trying to discover how it works. We use our instruments to bring people together. We know that it will always do that. The instruments that we use in Africa are sources of communication. The other aspect of it is that we use it for healing. That's an important aspect of drumming in African music, the polyrhythmic nature. We know that rhythm is the soul of life. Every cell in your body and mine is in constant frequency, in rhythm. Everything that we do is in rhythm. So that music, it attracts, it energizes every cell in our body. We're trying to find the answers of how music can be used to heal. We will come to it somehow, but words are not adequate to describe how you feel, if you are tired or if you feel competitive. But once you start, the adrenaline flows, you become more energetic, you feel something flowing through your whole body. You can't say what it is but it is something powerful. You feel in excess of it.

That's what happens. That aspect of it is what I

know that has come to maintain the validity of that. But we know it heals.

It heals. So for me personally, it has helped me, healed me through many,

many conditions. I know that if it effect me, it effects others. Definitely.

PSF: You were talking about how African music informed other styles. When you were playing with jazz musicians such as John Coltrane, what kind of common thread did you find between your work and theirs?

In talking about jazz, you call it a phenomenon that has been born from so many sources. Africa's contribution to jazz is rhythm. The jazz musician (like Coltrane) with their hands, do improvisation. With that going on, there is a steady beat, a heartbeat. The same thing in singing- call and response as you have in gospel. "Oh happy day, happy day." You have African rhythms, revisions of African traditions.

In the way of life of people in the area of arts, it's the same thing when you think about it. People who are very, very eloquent in the sense when you go through times like Ozzy Davis, people who are natural at things. People who can recite verses. People who have memory retention. The style of presentation. You have blues singers who through their songs, tell stories about their lifestyle or the lifestyle of the people they deal with and what is happening in their immediate environment, how they feel about life in general. What is their emotional feelings about subject matters like love, like pain, like wealth, like death and God? Through their songs, through their renditions, they let this all out. And how they feel about the one that gives them the most pleasure. That's an African tradition that has survived the test of time. It's something that will carry on.

As you move from North America to South America, the retention of African tradition even becomes more powerful than it is in North America. The continents were not really separated as they were with North America. So if go to Surinam, you can see a whole village of nothing but Guyanians who are carving the same way that they are doing in Surinam. If you go to Trinidad, you can listen to people who are chanting the same songs to the God of thunder as they do in Nigeria. If you go to the oriental province in Cuba, where Mongo Santamaria came from, they have the same way of live and the same way of talking is practically the same thing as a Guinea tribe. The same thing in Guyana, the South Sea Islands. It's all over. That's how the contribution of African culture, development of world culture, has been very tremendous.

PSF: Talk about how you present your albums as part of a cycle.

The first one was actually a signature to let people know what African percussion is all about. We put it together to make music. It really speaks for itself. What I am hoping to be do… You know, for twenty-eight years, I didn't collect any royalties. I was so excited that when I signed the contract, I didn't read it! (laughs) I didn't cross the T's and dot the I's!

It's like seeing a vision of what's going to happen. That's why I changed course, foreseeing the whole idea of diplomacy that I was studying for. At that appearance at Radio City in 1958, I had been here eight years and in 1957, Ghana became independent. I was getting 500 dollars a week so I was able to save money. I was invited to a very important meeting in Ghana- the All African Peoples Conference held by President Kwame Nkrumah in 1958. So I was able to go Ghana- that's when I was elected President of the Student's Union (at Morehouse). I was very political in those days. I had a degree in diplomacy so I had to organize African students from all over.

I went to that meeting and read a paper at the conference. I was a non-voting member because I was a student. In essence, I said that there should be a cultural center in every major city in America so as to disseminate information about the rich cultural heritage of Africa to correct the ugly image of Africa in the mind of Americans. The President applauded the speech and the next day, he called me and my wife to his castle. He said 'that was a great thing- why don't you just pursue that (drumming)? We will be able to help you.' So the first drum set I had for Drums Of Passion actually came from Ghana. I didn't have money to buy drums in those days. I was just leeching around, using a few conga drums that I rented. I didn't get that set until years after I graduated from college in New York in 1954. This was four years later!

Drums Of Passion was the first album. I didn't know that I would get a contract but we would rehearse every day, Monday through Sunday. Those who say they were gonna charge us, they say 'when you're finished charging, you come over here.' This group was mainly African-Americans, some from the islands. We came together and we were a very unique group- they were interested and eager. That was the beginning of it. From there, it became a necessary way of life with me to pursue and looking for support from abroad and from here. That led to the establishment of the Olatunji Center of African Culture.

It was all the period when the late Alvin Alley would watch us rehearse. That was before he started his company. We would present modern jazz groups and they perform with us. We started the Olatunji Center in Harlem then (1967). That was our first home- the center had been operating but without a specific home, using different spaces. Before that, we formed at the World's Fair, 1964, 1965. We were the first African group in this country to perform at the World's Fair. The audience at the African pavilion was the most popular one at the Fair. The money I made there, I used to open the Center. I couldn't buy a building though so I had to pay $15,000 a year for to rent a loft space. Coltrane was one person who was sending $250 every month to help. Then later on, he did not perform for two years and the last performance he gave was where? At my center. He was very concerned about the way that promoters were cheating the musicians. They go and borrow money from their cousins. They would play at Carnegie Hall and make $50,000 for the show and then they pay them (musicians) scale wages. It was unequal distribution of wealth.

So he (Coltrane) said, 'I want to deal with this and do some research and see where I am, learn what I can learn about Western music and jazz.' He was following me at that time. He came to me and said 'you and me and several other people like ourselves should come together. We know how to promote shows. How about three groups? You want to have a center in every center in America? We can do that? Your group, my group and Yusef's (Lateef) group can start with Lincoln Center and we'll raise enough money.' I was appointed Secretary-treasurer. I went and booked the first concert for January 1968. Trane passed in 1967 though.

The center was also there for the purpose of bringing back what I read about Harlem. Things were so different. You had black and white (people) everywhere. So I was wondering why it wasn't happening again? So I instituted a Sunday afternoon program called 'Roots of Africa'- the program had a picture of Africa with Coltrane in the middle. So we performed, Yusef performed, Pete Seeger performed, Bill Lee (Spike Lee's father) performed with eight bass players. That hasn't been done again. It was done right there at the center. It was really going well. I had somebody different every Sunday afternoon, all for two dollars! That's it! (laughs) I had been surviving without any foundation support. I would write for grants, do proposals and hear back from the Ford Foundation 'we do not fund your kind of program.' The first money I got was from the Rockefeller brothers: 25,000.

Then from the National Endowment of the Arts, we got a grant for our teacher training program. So most of the most of people you see teaching African dance were trained there. We went to all over the schools in the tri-state area, all the way to Long Island.

That's where I met Mickey Hart (Grateful Dead). He

was at one of the schools where they had the African program. I always

asked the students to come and beat on the drums. He came and did it and

I said "He's good!" That was 25 years ago. It wasn't until November 1985

in San Francisco that I met him again at one of the Bill Graham theatres.

Mickey was coming from a (basketball) game and he brought Larry Bird to

meet me after the show. He was helping with the sound and the whole place

was dancing with drums. He said "You don't remember me but I want to tell

you something... It's because of you that I'm doing what I'm doing today.

What are you doing tomorrow?" I didn't have any plans. So he says "OK,

you're going to open for the Grateful Dead." That was December 1985. It

was at that time that Columbia refused to renew my contract. That was George

Butler- he might have recognized that I'm a legend but he didn't go for

my kind of music. I said "You told me that my first record wouldn't sell

and you know it did!"

PSF: Could you talk about the other bands and performances you were doing at clubs during the 1960's?

I started experimenting back then, when I started. I had my jazz combo and we used to have 12-13 weeks at Birdland (New York). We used to open for all the big bands. We would also close out the shows at 4AM. In 1960, 1961, you had the bands like Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Quincy Jones. I got to meet a lot of the Europeans too because when they came to New York, they'd arrive late. And where would they go then? Birdland. It was a fascinating period.

Then for a ten-year period, nothing was happening for me. The Center closed because we kept missing the rent. I didn't get any support from the city. They could have given me a building for one dollar because we were non-profit. None of the middle-class blacks gave any support for my effort. They did not send their kids to my school. I picked up kids that used to sell drugs in Harlem just to (earn money to) come upstairs and drum. I didn't get ANY support. It was humiliating. It was so devastating that here was an opportunity to help these people to have an image of themselves. They were talking about kids not doing the right thing. But they didn't do the right thing by them. I used to walk between 126th Street to 138th Street and I saw that those kids didn't go school. They walked around, had nowhere to go. So I took them upstairs and had them play drums. I was charging two dollars and I wasn't just teaching them about drums. I was teaching them history, culture and I offered them 12 languages. The history about themselves. If they ever knew who their ancestors where, they would want to do the right thing.

But they (the parents and adults) didn't do anything

about the situation. I think the same thing is still going on now. The

answer is not spending millions of dollars to go on television and tell

people "JUST SAY NO." That's not the answer. You got to do what Malcolm

(X) said. He put it in the street language- "Stop it downtown and it won't

come uptown." You know who the people are who are bringing these things

in- those are the people you need to stop. You need to fortify the borders

so that no one can bring any drugs in.

PSF: Did you find any support among the colleges?

Integration came on college campuses where I used

to go all over the world. I was being sponsored by the entire university.

Now, the black student unions would want to sponsor me but they don't have

no money. It's black backlash that I experienced. I used to go to Kent

State to perform three times a year. Now, I can only go once because the

student union can't afford it. The black student union gets very little

money and they want to do so much. They can only pay me a fraction of what

I was getting before to tie the drums to our car and drive all the way

out there. We used to do that- drive all around the country in those days.

It was devastating. It was so heart-breaking to see what was going on in

those days. But now, everyone is playing drums.

PSF: In your groups, how do the drums communicate with each other and interweave with the singers?

The African theatre is a total theatre. You cannot write a dramatic play without song and without movement. The trial is lost if you have a presentation that does not address ALL aspects of the music. The dancers must be able to dance with the beat of the drum. The drummers who play for the dancers must have knowledge of the dance. That's the only way that they're going to be able to play adequately and professionally. That's how they will be able to communicate with them.

Not until recent times have I been noticing in Western theatre, in Broadway shows, the people who audition must be able to sing, dance and act. That was never a problem with an African performance. Automatically, he or she is trained right from the start to be able to combine all of those parts together. This is no sense in the whole presentation that the drummer does not know the dance. He must know the dance- the required changes necessary in the choreography of the dance. Not only in tempo, in intensity, maybe to a completely new interpretation.

In the other words, the dancer and the drummer have

become one. The drummer as well as the dancer has the ability to sing along

as they perform. It is part of the whole presentation. That is normally

taught from the beginning of any particular presentation or production.

PSF: Do you also have a sense that the drums are interacting with each other?

The drummers between themselves are interacting and communicating. Irrespective of the number of drummers involved in a presentation, each drummer is given a part to play for the whole. He must know where the change is from one part to the next. That's (been) happening for thousands of years.

A lot of people go about teaching African dance but

they don't teach the music. They just play for the dance. Every traditional

dance that's been passed on from time immortal is all music, unless it

is a new work. So (then) you got to write the music for it. New choreography,

new music, new costumes. But the interaction among the drummers is very

clear that you don't jump into playing rhythmic patterns unless there is

a reason or the group can help bring you back as a reminder to say 'this

is what you're supposed to be playing.' All the musicians know the parts,

including the part of the lead drummer.

PSF: I had heard that you performed at a celebration here for Nelson Mandela. Could you talk about that?

There were 120 clergyman at Riverside Church of all

denominations in the community. They had a special service for Mandela

when he first came here (1990). It was my group that led him into the church,

with the drums and the chants. I led him to his seat and then performed.

From there, the group also performed at the reception given to him at Yankee

Stadium. I also followed him out to San Francisco, which was also organized

by Bill Graham. I am looking forward to going back to San Francisco to

discuss a project, the Voices of Africa.

PSF: How has it felt to be an expatriate here in the States, playing the music from your homeland and occasionally going back there to perform?

Well, I'm a citizen of the world now. I am very concerned about what has been happening in Africa. What I've been doing here... I wanted to repeat (my) performance in Africa. I want to be going around now, reminding people that in our quest to become totally free as we pursue our goals, we need to remember and put into place all of the traditional wisdom that will help us survive in the new millennium. We need to re-institute some of our traditional values that seem to be evaporating in our society now. That is to restore our traditional ways of life in the areas of culture, music, arts that has helped us define what we call the African personality.

In my estimation, we are in an educational pursuit.

In the Western world, we have neglected those traditional values. So it's

what I call 'misplacement of values.' Unless we go back to restoring them

into our lives, we're going to have trouble- a lot of misgivings among

our own people in the very near future. A lot of young people are clamoring

now to find out 'what is it that we can call our own? What is it about

our heritage?' They want to know. These times now make them very, very

aware of that.

PSF: Do you see your work as carrying on tradition and bringing a message to people?

That's exactly what I'm so grateful about. I may not have any money to show about it but what I have started here, from five years ago, is like planting a new seed that is beginning to germinate. It will come out very well. I'm quite sure that the leadership will become very, very concerned about the need for looking into the past. The past and the present are inevitably put together. What we had in the past is what we have today- it will make a wonderful combination for tomorrow. Then we cannot let time go by without taking care of that particular aspect of our development now, especially if we try to patch up the rest of the world.

If we're really going to catch up, as they say, he who is behind must run faster than he who is in front. That's if you want to catch up. And we need to catch up with the rest of the world. Africa needs a very strong leadership, compassionate leadership. We need someone who will really want to serve the people. You have to be tolerant and be able to listen and do the right thing by the people.

You look at this country and how they spend all the

money buying arms. Who are we trying to fight? They spend 12 million dollars

to save 1 million people in Rwanda. Why didn't they raise that money years

ago to prevent what happened there? The military annulled the election

and go away with it and we were doing business with a tyrant.

PSF: How do you think your work has evolved?

The music has not changed, but it has evolved. I had been able to incorporate my musical experiences in different CD's and albums. I have always had a message. At the same time, (I) make sure that the foundation of what I'm presenting is still tradition. My recent album, the subject matter is love. I let traditional percussion music be very, very strong there. It was overpowered by other instruments. I wanted people to experience how it could be done without the use of synthesizers and hard rock instrumentation. There's always a message about each CD that I put out. So, I have been very careful about that. I think every student of African music, even Africans themselves, needs to make sure that we don't lose that touch. We should really maintain the roots, the strong background that we have. That our performances really be a signature of where the roots of the music come from.

There is no doubt in my mind (that) we all go through a process of incorporation. No matter who you are or where you are, you will be effect by an environment. But nevertheless, you cannot afford to lose yourself. Being how you are. I will always make sure that you have a taste of that particular instrument, the drum.

PSF: And the voice too.

Yes, of course.

PSF: You have a very impressive range.

Well, I am proud of that. I had attended a session

with a voice teacher from Boston who had trained many singers and politicians.

So I sang for him " Do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do!" He said "what a voice- what

conservatory did you study at?" I said "Conservatory? I studied in the

bush! The village was my conservatory."

Also see some of Babatunde Olatunji's favorite music

Also- Olatunji's official website