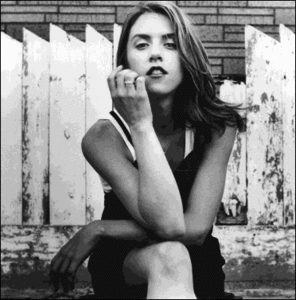

Liz Phair

Phair Without Fear

by Sarah Beilenson

(August 2015)

Phair Without Fear For the cynics and sinners, the sluts, whores, and bitches, the prudes and the teases; for the disenfranchised and the abused; for those without agency or a voice—for all women:

I'm writing this piece because I'm tired of all the shame I've inherited from the rock music I love so dearly. I'm tired of explaining myself, tired of justifying. But in recent years it's been the shame I feel for being ashamed that I wish to shed. The following is not an admission, it is a statement of principle: I love Liz Phair. I propose that women (especially in the music scene) will never have equal footing, until we are able to stop being so cruel to one another. I don't know why we criticize each other for sport—maybe to prove our individual "belonging" to the boys club or some equally stupid reason.

To my generation the name Liz Phair recalls endless slander and mockery, if anything at all. "But the point about Liz Phair," says Gina Arnold in a review of Whitechocolatespaceegg that's the best piece of writing I've found about her, "has always been her ability to expose us to our own prejudices." And my cohort of aspiring feminists could use more of that.

Elizabeth Clark Phair was born on April 17, 1967, in New Haven, Connecticut. The adopted child of Nancy and Jon Phair (an art historian and doctor), she grew up in the affluent North Shore suburb of Winnetka, Illinois (think Ferris Bueller's Day Off).

In 1990 Liz Phair is your archetypal twenty-something woman: a little lost, a little frustrated, and, occasionally, a little hopeful. Having recently graduated, "by the skin of [her] teeth," from Oberlin with a degree in art history and studio art, Phair drifted from coast to coast—briefly assisting various visual artists in NYC before bumming around San Francisco with fellow Oberlin grad and collaborator Chris Brakow. "I did nothing of any value whatsoever [in San Francisco]," she admits. "Like we would get up in the morning, get high, drink coffee, get dressed... I had so much fun... whiling away the hours..." But "fuck[ing] around" amounted to more than just a good time. It was in San Francisco that she recorded her first songs—on a dare. Eventually running out of money, she returned to Chicago to "get [her] shit together." AKA selling charcoal drawings in Wicker Park, and more importantly, recording in earnest. Under the moniker "Girlysound," her homemade tapes began to circulate through the American indie underground.

"Those tapes were all intentionally about using a little-girlish voice to say really dirty things and play with pedophilia.... At the same time [I was] titillating them, [I was also trying] to bring them close enough so I [could] smack em'."

By May of 1992, Liz Phair landed a record deal with New York indie label Matador. A year later, she released Exile in Guyville and left the boys of indie rock standing on their heads with their dicks in hand. Songs like "Flower" (in which she aspires to be your "blowjob queen") and her calculated use of the word "fuck" garnered significant male attention, fanatical reviews, and critical acclaim. The sexplicit lyrics are few and far between, but that didn't keep the media from focusing on them. I'm not saying the sexual innuendos and the downright dirty weren't important. They were! Her agency and candid sexuality introduced the mainstream to third-wave feminism. She was the second-ever woman to be voted album of the year in the Village Voice's Pazz & Jop Critics' Poll—the first being Joni Mitchell in 1974, nearly two decades prior. She didn't achieve this kind of acclaim merely by talking dirty, but it's difficult to find a review from 1993 that actually focuses on her craft. Even in many retrospective reviews her musicality is still largely underappreciated (cf. "Strange Loop," which has inspired endless posts regarding its mysterious tablature, as fans try to discern by ear and via live concert footage what she is actually playing). She's not a virtuoso in the manner of Liszt or Hendrix, but she plays her own weird made-up chords—often spanning more frets than thought humanly possible, especially for a woman of her size—and possesses a unique sense of rhythm to boot. Take "Canary" for example. It has no rhythm track and the piano is so wet it's bleeding to death and the delay has me wondering about which is left and right and where one chord ends and the next begins. I don't understand it, but it works—her balladry is never stagnant. "Canary" is no exception. It speeds up and slows down at the drop of a hat and is always at her croon's beck and call.

Detractors have tried to take a swipe or five at Liz: she can't sing, she can't play guitar, she didn't "pay her dues," she's skating on the success of the Rolling Stones, and/or, in the elegant phraseology of former Rapeman frontman Steve Albini, a "pandering slut." I'd like to point out that not all genres of rock music consider virtuosity a necessity, and punk ignored it altogether. Furthermore, it was Phair's compelling vocals that drew me towards her in the first place, at around 11 years old. I had no idea this record was such a loaded topic. I just liked it. She wasn't trying to sound pretty, but she did anyway. She pushed her voice to its limits, excavating from quavering falsetto ("Flower") to guttural lows ("Glory") without ever caricaturing her protagonist..

Whitechocolatespaceegg (1998)

After a four yearl hiatus from music Phair returns on the scene in 1998 with Whitechocolatespaceegg. In the interim she did the unthinkable: she got married and had a child. This new chapter of her life emerges in the sonic and lyrical quality of this largely underrated record. There are fewer curse words and more stories. The overall sound is clearer—allowing her songwriting to really shine without sounding overproduced. She ditches confessional-style lyrics to take creative liberties on this record. Instead, she sings from the perspective of many different people, both male and female. "Shitloads of Money" is about a man who forgoes his morals for a better paying job: "It's nice to be liked/but its better by far to get paid." "What Makes You Happy" is a strikingly heartfelt song about failed relationships and hope, a conversation between mother and daughter: "I'm sending you a photograph/ I swear this one is gonna last/and all those other bastards were only practice." To which her mother responds: "Listen here young lady/ All that matters is what makes you happy/ But you leave this house knowing my opinion /It won't make a difference if you're not ready." Her talent on this record is how much subtext there is in her writing. There are hardly any more lyrics in that song, but the few lines we get are enough for us to infer a lot and to fill in the details as we imagine them.

The writing is also catchier, if not a bit more pop ("Polyester Bride") than on her previous records. Unfortunately, after Whipsmart (1994) many of her fans are either pissed off or disinterested, and this record goes largely unnoticed. But if you only listen to one track, As Gina Arnold puts it: "The record ends with `Girls' Room,' a gentle reminiscence of the slightly bitchy chitchat of adolescent girls. It's a song that exemplifies what makes Phair so great: the way she has managed to elevate the American white girl's inherently shallow experience to the subject of great art."

Liz Phair (2003)

The year is 2003. I am eleven years old, sitting in the passenger seat of my mom's Buick. We've reached our destination: the Palisades Mall. We've even found a parking spot. The car is in park but the engine is idling because we're in the middle of a song—a somewhat regular occurrence in my family. In fact, we're in the middle of singing a song: "I am extraordinary if you'd ever get to know me/I am extraordinary, I am just your ordinary/average, everyday, sane, psycho, super goddess ..."

I remember when Liz Phair (2003) came in the mail (my father, the "tastemaker," was in charge of purchasing new releases every few weeks or so). Now, exactly 11 years after that, I pester my parents about it: my mom admits to liking it, my dad not so much, but he makes a point of reminding me that my mother usually hates female singers, listing a few off the top of his head: Janis Joplin, Jenny Lewis/Rilo Kiley, Tracy Chapman, Grace Slick, Neko Case, Ida Maria...

Pitchfork famously gave this self-titled album a 0.0. What a tantrum! A 0.0 goes beyond matters of taste—regardless of whether you liked the record or not, it's not a 0.0. If it were really that bad no one would waste the print. In the realm of pop music, breaking into top 40 is perhaps the clearest indication of success. In the decade that lapsed between Exile in Guyville and Liz Phair indie rock was wilting and despite her steady output, she had almost completely faded back to the obscurity whence she came. "Rock Me" acknowledges this: "your record collection don't exist/you don't even know who Liz Phair is," she notes of the much younger man she is sleeping with.

This record isn't my favorite, or even my second favorite, but I cherish it as much as I do the others. It's difficult to comprehend why seemingly no one is ever happy for Liz Phair. Yes, this record was released by Capitol. Yes, it's a pop record. Yes, it was partly produced by Avril Lavigne's team, the Matrix. And, yes, it's good.

I didn't revisit this record until I was about twenty, living and working in Los Angeles. My friend and I shared a beat-up green Prius with a license plate that read "Highway 61" and one of those hippie "eARTh" bumper stickers. It served us well—we had recently driven across the American southwest from Austin to LA without major incident, but all we had at our disposal was a CD player. I made about 10 hours worth of mixtapes, which proved to be a wild underestimation of both quantity and quality. Upon arriving in LA, and spending just about the same amount of time on the highway—albeit in traffic rather than the open road—I promptly burned several more CDs. I don't know how many I made, but I do remember that Liz Phair (2003) was in heavy rotation. Apparently, there's a lot of shit you don't understand when you're eleven. For example, Liz manages to slip "HWC" onto the record. That stands for "hot white cum," as in: "give it to me/ don't give it away" and a chorus that goes "give me your hot white cum." X4.

Today (2015):

Today, Liz Phair makes a living writing music for film and television. Her work on the new Beverly Hills 90210 even earned her a Grammy nomination. It's impressive that Phair has, for decades now, managed to continually carve out a space for herself in the music business despite the seemingly endless hate-storm.

After the controversy and buzz died down, Liz Phair recorded several "indifferently received" albums, for Atlantic and Capitol respectively. In 2008 Dave Matthews' ATO label re-released Exile in Guyville, but dropped Phair before an album of her new work, Funstyle, could be released. So she released it herself. Again, the Internet is up in arms over this chick.

Don't you get it? She's been toying with us for a while now. I love Phair for being an instigator—for fucking and running, for being our blowjob queen: a prankster, a rapper, a mother, an indie goddess, and a "pandering slut." She's a little bit of all of us and she'll take the heat for us too. Because I think she knows, like I know, that she recorded one of the greatest rock records of all time: Exile in Guyville. She did that all on her own, and no amount of slut-shaming or ridicule can take that away from her—from us.