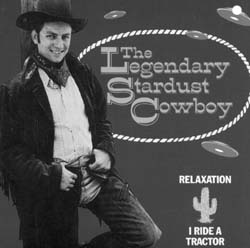

Wide-Open Space Cadet

by Irwin Chusid (June 2000)

from Songs

in the Key of Z: The Curious Universe of Outsider Music

(© 2000, A Cappella Books)

Author / producer Irwin Chusid's book profiles dozens of outsider musicians, both prominent and

obscure, including such figures as The Shaggs, Syd Barrett, Tiny Tim, Joe Meek, Jandek,

Captain Beefheart, The Cherry Sisters, Wesley Willis, Daniel Johnston, Wild Man Fischer, and Harry Partch. The text presents their strange life stories along with photographs, interviews, cartoons, and discographies.

"We re driving along New York's Taconic Parkway, me and the man who would later be my husband, and in this misplaced effort to impress him, I put on my tape of the Legendary Stardust Cowboy," recalled lawyer Diana Mercer. "I mean, we ve listened to the Velvet Underground, Sex Pistols, Captain Beefheart -- whoever, on this four-hour jaunt. He's at the wheel of my car, and the conversation is at a lull. I m looking to score some points, so -- what the heck -- in it goes."Before I know it, there s flashing red lights behind us, and a 6-foot tall African-American policewoman has pulled him over for doing 110 in a 55 mph zone. The ticket cost $310.

"Somebody was trying to tell me something," she sighed, "but I wasn t listening."

The Legendary Stardust Cowboy has been known to make people do strange things. Like sign him to a recording contract. Major labels aren t receptive to weirdness; they re in business to make money, not scare customers. Yet it was Mercury Records who propelled the Legendary Stardust Cowboy (a.k.a. "The Ledge") into the marketplace. In 1968, the label released his 45 rpm single, "Paralyzed" -- a blast of Texas no-fi wreckage, two-and-a-half minutes of Indian whoops, rebel yells and caveman cretinism -- that forever staked this unforgettable vocalist s claim to fame. The acquisition of this pan-galactic buckaroo might have occurred during some Mercury exec s weeklong bender, or during an A&R veep s peyote peak.

Artistically -- and psychologically -- the Ledge comes across like someone who drove through the carwash with the top down. This bedlam-prone prairie dawg earned notoriety for his uninhibited howling and utter vocal abandon, oblivious to such quaint notions as euphony, rhythm, and restraint. His oral artistry consists of the astonishing number of ways he can emit musical sounds -- without actually singing. Besides the rebel yell, the Commanche war whoop, and hog hollerin , he s mastered elephant cries, birdcalls, frog croaks, and a menagerie of jungle squawks. The man wails, cackles, and belches; he grunts, growls, and taunts. When the Ledge goes mano a mano with a song, melody goes home with a bloody nose every time.

Despite his hyperactive exuberance -- bellowing like he's just been goosed -- the Ledge isn't threatening or scary. His "singing" voice is a friendly baritone, his vocal chords slightly constricted. Imagine a kiddie-show host whose jockey shorts are too tight. Yet the Ledge speaks in a warm tenor, up in fellow Texan Ross Perot's register. (The comparison stops there.)

There s a lack of attitude in his personality and lyrics, which are imbued with self-deprecating humor. He s lived life as a musical outsider, and been reminded often enough that his "talents" are not welcome in some quarters.

The Ledge s records are sheer fun -- if you re ready for a wild ride. "Paralyzed" was described by journalist R.J. Smith as "one long woof of defiance that sounds great at any turntable speed." Along with creek-rocker Hasil Adkins, the Ledge provided stylistic threads for cowpunk and psychobilly, inspiring such voodoo-tinged twangers as the Cramps, Meat Puppets, Butthole Surfers, and Raunch Hands. His more celebrated fans include Brooke Shields and Elvis Costello. Among the Texas roots posse, the Ledge is beloved by Butch Hancock, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, and former school-chum Joe Ely, all of whom proudly call him a friend. Ely, in fact, considers him "West Texas greatest jazz musician."

The man has left his mark on at least one certified superstar. When David Bowie signed with Mercury in the US around 1970, the company gave him a stack of 45s as a welcome-to-our-label gift. Among those singles was "Paralyzed." "That was the one he liked best," affirmed Ledge chronicler Tony Philputt, who directed a 90-minute film biography of the Lone Star lunatic. Thus inspired, Bowie appropriated part of the singer s name for his US breakout album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. "Apparently, Bowie was obsessed with this character, and never knew anything about him," Philputt elaborated. "This was up until 1998. A reporter in Chicago who did a story on the Ledge got ahold of Bowie through his management. Bowie still knew nothing about him. He was amazed the Ledge was even alive. On Robert Plant's first solo tour after Led Zeppelin split, before his set, he played the Ledge s Rock-It to Stardom album over the hall P.A."

The perpetrator of the feral "Paralyzed" is a relatively mild-mannered pussycat. Before he adopted the guise of the Legendary Stardust Cowboy, he was Norman Carl Odam, born September 5, 1947, in Lubbock, TX, to Carl Bunyan Odam and Utahonna Beauchamp. He was a shy youngster; he says it took his kindergarten teacher six months to get him to talk. One of his earliest recollections is that at age 7, he knew he "would like to go to Mars instead of the Moon." In school, he distracted himself by scribbling poetry and short stories. He also began developing highly idiosyncratic vocal techniques. "When I was 14," he wrote in a 1969 autobiographical sketch, "I started doing Rebel yells and Indian whoops because I am part Shawnee. I taught myself to do birdcalls and jungle sounds." With this odd array of mouth noises, he began vocalizing around school, hoping to achieve some measure of celebrity with the opposite sex. "I figured that by singing I was able to attract all the girls," he explained. "But I attracted all the boys instead."

The popularity of picker Chet Atkins inspired young Odam to take guitar lessons. He never mastered the Countrypolitan king s smooth fingering, but he did teach himself drums, kazoo, harmonica, buffalo horn and the rub-board. He acquired rudimentary bugle skills by riffing along with LPs by Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass. His early (unrecorded) repertoire consisted of country & western songs popularized by Johnny Cash, Ray Price and Buck Owens. Along the line to post-adolescence, like a kid tossed from a dimestore bronco once too often, Odam evolved into an authentic frontier wacko.

He also became, from time to time, an unfortunate victim of circumstance. The Ledge s life -- like his music -- has always been slightly beyond his control.

Joe Ely was a classmate at J.T. Hutchinson Junior High in Lubbock. "The first time I saw Norman," recalled Ely, "he was playing on the steps. He d get to school bout 7:30 in the morning, before everybody else. He d do a whole set before the bell rang. He just kinda wailed on at the top of his lungs. [Later,] Norman carried on this tradition and played on the steps of the high school." He invariably attracted crowds -- girls even -- and his extracurricular notoriety grew. But he still couldn t get a date. Not all his classmates took his performances seriously. Some considered him a freak. They d honk their horns, throw dirt clods and Sweet-Tarts. Others flung pennies and peppermints in the hole of his guitar.

At some point in his teens, Odam merged two great obsessions -- the Wild West and Outer Space -- and decided "The Legendary Stardust Cowboy" suited him better than "Norman." He spray-painted the name -- preceded by "NASA presents" -- in big gold and black letters across the side of his new Chevy Biscayne (much to the horror of his grandmother, who took a swat at the teen for ruining a perfectly good automobile).

He couldn t get gigs at local clubs, so he obsessively sang in public: at frat houses, outside the Dairy Queen, in the parking lots of the Hi-D-Ho Drive-In and the Char-King. His makeshift stage was the roof of his Chevy, on which he d painted a map of the moon. His atavistic caterwauling was accompanied by St. Vitus gyrations copied from another hero, Tom Jones. Usually management would run him off the property.

Odam would turn up unexpectedly at parties and give impromptu -- and often unwelcome -- performances. He occasionally found himself the target of spectator intolerance. When he plied his raucous repertoire in honky-tonks during the late 60s, he sported long hair and muttonchop sideburns. "Old time country music fans thought I was making fun of them and country music," he recalled. "Owners and managers of clubs had to pull away people trying to get close enough to beat me up." One night at the Hi-D-Ho, an onlooker heaped ridicule on the Ledge s performance, but he ignored her and kept singing. "He either laid his guitar town, or she came up and grabbed it," said Ely. "All I remember is turning around and seeing the front of his guitar cave in, with her foot going through it. It was a sad day. That guitar was his main squeeze."

After high school, Odam resolved to travel in search of fame. Las Vegas. New York. Hollywood. Other planets.

Instead he took a bus to San Diego. Unable to land a paid gig, he moved to L.A. and tried to get on the Steve Allen Show and Art Linkletter s House Party, but no one was booking unrecorded amateurs who specialized in coyote howls. Disillusioned, he returned to Lubbock, worked in a warehouse, and played local clubs to largely skeptical or indifferent audiences.

In 1968, he tried to contact the best known musical Outsider. "I wrote Tiny Tim a letter," he recalled, "with a picture of myself and musical instruments. I wanted to be on the Johnny Carson show like [him]." Tiny never replied. (Considering the magnitude of his then-popularity, it s unlikely he ever saw the letter.)

With $160 in his pocket, the Ledge aimed his Biscayne at New York. His goal: the Tonight Show. He had no manager and no demo tape. He also had zero business smarts.

He never made it to Manhattan -- but along the way, the "legendary" part of his name became a reality.

He pit-stopped in Forth Worth, 300 miles east of his hometown. Two vacuum cleaner salesmen, headed out to a local club, spied the Ledge's graffiti-blessed Chevy in a parking lot. They chatted with the driver, and noticed he had what they thought was a guitar. The vac dealers knew the club owner, so they invited Odam along to perform. After witnessing the musical demolition derby that is a typical Ledge showcase, they whisked him to a nearby recording studio, where he auditioned an original song for a young engineer named T-Bone Burnett.

A sense of urgency prevailed -- who knew if this transient would be around next day -- so they spooled up a reel of tape and hit "record." T-Bone leapt to the drumkit, the Ledge grabbed a mic, and "Paralyzed" was born. The Ledge s aboriginal shrieks and freewheeling bugle brays were underscored by Burnett s furious, not quite-metronomic drumming.

It was an early morning session; the engineers had been up all night messing around, and the whole fiasco seemed half-hallucinatory. "The band was just me on drums, and he had a dobro with a broken neck, so he could only play on the first fret," Burnett recalled. "We just set up two microphones. [The staff was] in a state of sleep deprivation that probably caused us to be more daring than we might ve been otherwise. Norman gave me some instructions -- Play drums in the same tempo I m singing in -- and I said, I could do that. [laughs] Maybe probably. Then he said he was going to take a bugle solo, and he wanted me to take a drum solo, and I found that all agreeable. It was explosive, to say the least."

Upstairs in the same building was KXOL, the only Top 40 AM station in town. Burnett ran upstairs and played the tape for the wake-up jock, expecting a rebuff. Instead the host ranted, "THIS IS IT! THIS IS THE NEW MUSIC!" The song was aired several times, the switchboard overheated, and T-Bone knew they had a hit on their hands.

"This is something, by the way, to highly recommend Fort Worth," chuckled Burnett, "that the people could love this and embrace it so instantly."

The studio stamped 500 copies on the Psycho-Suavé label. After some initial regional commotion, the single was sold to Mercury Records for national distribution. The deal was brokered by sleazy Fort Worth music impresario Major Bill Smith, who brazenly claimed production credit.

"Paralyzed" embodied some of the most mutant strains ever pressed on major-league vinyl (at least til Harry Chapin got signed). It cracked the Billboard Top 200 -- no mean feat for a record that even by the drug-addled standards of 1968 was irredeemably in orbit. It brought the sagebrush spaceman instant fame, if not fortune.

Of course, not everyone "got it." "Paralyzed" frequently hovers near the top of smart-alec rankings of the "all-time worst recordings." British TV comic Kenny Everett compiled an album entitled, aptly enough, The World s Worst Record Show; "Paralyzed" shares the LP s furrows with such deeper dumpster pickings as "Why Am I Living?" by Jess Conrad and Dickie Lee s "Laurie." Clayton Stromberger, in a zine called No Depression, described how "out" the single was: "It was out the window that noted music critic Ed Ward s first copy of Paralyzed went sailing after his first listen ... in 1968. He ripped it off the turntable, pronounced it the worst song he d ever heard, and flung it as far as it would go. Which of course only added luster to the legend of the Ledge (and left Ward kicking himself years later)."

See Part 2 of Legendary Stardust Cowboy

| MAIN PAGE | ARTICLES | STAFF/FAVORITE MUSIC | LINKS |