Ishmael Reed

Neo-HooDoo, in Words and Music

by W. C. Bamberger

(April 2010)

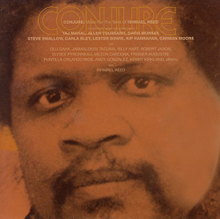

Ishmael Reed is a novelist, playwright, editor, critic and poet, among other things. From his earliest writings he has created his own compass points, his own sensibility, "Neo-HooDoo." This is made up of elements gathered from his studies in history, Egyptology, numerology, mythology, politics and popular culture--virtually everything he has come across that strikes him as rhythmic, mysterious, a tool for truth and self-defense, or creative in any positive way. Reed's choices reflect his insistence that a good life should include style, mystery and music--including word music. In 1984 Kip Hanrahan--producer, percussionist, and hand at the helm of the American Clave label--gathered together more than a dozen singers, musicians and composers to create Conjure: Music for the Texts of Ishmael Reed.1 The names of the giants of jazz, blues and Latin music who chose to accept Hanrahan's invitation--Taj Mahal, Allen Toussaint, Olu Dara, Steve Swallow, Carla Bley, Billy Hart, Lester Bowie, and more--are a measure of how respected Reed's writings had become.

Conjure opens with "Jes' Grew," (a reference to Topsy in Uncle Tom's Cabin), a reworking of passage from Reed's 1972 novel Mumbo Jumbo. The words both celebrate the eruption of black style in the early decades of the 20th century, and lampoon the strong resistance (always shot through with infatuation) of the established white High Society. David Murray composed the music, an all-akimbo funk counterpoint, with Allen Toussaint's piano sparring with two electric bass players and hairpin-turn horns. The lines ceaselessly cross and layer and swerve. Taj Mahal handles lead vocals here (as he does on most tracks, at times with overlapping counter-lines by background singers): "When we call it one thing, it turns into something else / Slippin' and dippin' and gliding on out into the street... Will this mean the end of civilization as we know it?" The setting of prose sentences to music produces a very jazzy, slippery melody that Taj executes with a laid-back mastery. Bley's music for "The Wardrobe Master of Paradise" is conga-driven, Latinesque but bluesy. "He does not sweat the phony trends or fashion's dumb decree," the lyrics (originally a poem) declare--and neither do Reed or the musicians here. They are out-and-out making their own stuff. Murray contributes a scribbled tenor solo, with Olu Dara's trumpet tacking up a simple back-line. The track ends with a slow fade-out of percussion.

I would set the brilliance of the first version of "Dualism" beside any blues-forged music I have ever heard. The aphoristic poem is about being taken up, devoured even, by history when Reed least expects it. Toussaint plays a soft sway on an R&B progression, Taj Mahal fingerpicks his Dobro while Billy Hart lays down a perfect New Orleans dragging-behind-the-beat snare drum, all behind a wheezing horn-line that would have made Jellyroll Morton cock his head and smile. Here and on "Oakland Blues" the always-brilliant Dara is given plenty of room to stretch out--the poem in its entirety is only a few dozen words long--and he solos with a broad old-style vibrato that captures the heart and puts a shiver in the lungs.

"Oakland Blues" is one of the more traditionally-shaped blues here. Kenny Kirkland's piano perfectly captures the between-major-and-minor feel, and Robert Jason's bronze baritone makes the heartbroken words believable: "They told you about that sickness only eighteen months ago / But you went down fighting, Baby, yes you fought death toe to toe." Here Dara squeezes the notes out--you can almost see him squint and grimace behind his horn. "Skydiving" is a philosophy of living with adversity, delivered with wry indirection:

Life is not always Hi-lifing inside Archibald Motley's "Chicken Shack" You in your derby Your honey in her beret Styling before a small vintage Car

Toussaint's music to this poem is primarily a two-chord stroll, Tousaaint himself on piano and overdubbed staccato organ.

The next track comes as a visitation: Reed himself, reading his poem "Judas"--"Funny about best friends huh, Lord?... See how careful you have to be about whom you go bar-hopping with, Jesus?" If we keep Reed's own voice-- its gruff timbre, its speedy dispensing of idea after idea--in mind, along with his insistence on joining parts of the traditional and the new into one sensibility, even as we listen to others' interpretation of his words, we get a better feel for the depth of even Reed's lightest works. "Betty Ball's Blues," for instance, is a blues of comic entendre: "Betty touched his organ / made his cathedral rock / His worshipers moaned and shouted / His stained glass windows cracked."

On the minor-key blues "Untitled (II)," Taj Mahal sings the complete poem--a single couplet--so the tune is primarily a duet Murray on tenor and Steve Swallow on piano, with the rhythm players so far back as to be almost unnoticeable. Bowie's take on "Fool-ology," the longest track here, features Bowie reciting the poem--in a wondrously comic-dramatic style, fully as Neo-tent-show as his unique trumpet style--over a box-spring-firm layer of bass and percussion. When Bowie half-sings "By the time they catch us we're not there / We're crows / Nobody has ever seen a dead crow on the highway," we know he knows how to live that very idea. "From the Files of Agent 22" is the slightest work here, a rather monotonous damped-guitar riff with congas and a blockish piano. Murray's solo helps, but the conga player wears out his welcome before the track blends into the second version of "Dualism," this time with Murray reciting the poem over the same annoying conga playing.

The recording ends with another recitation by Reed. "Rhythm in Philosophy" which tells us about a conversation Reed had with K.C. Byrd, where Reed describes a rhtyhm as being "conducted by a blue-collared man / in Keds and denims . . . in Baird Hall / on Sunday afternoons / Admission Free! / All harrumphs! must be / checked in at / the door." There is plenty of blue-collar rhythm on Conjure, and not a harrumph! to be found.

In the 1970 anthology 19 Necromancers from Now, Reed published the short Neo-HooDoo writing "Cab Calloway Stands in for the Moon."2 This title was taken for the second of the American Clave recordings of Reed poems set to music, issued in 1988.3 The feel here is somewhat different. "Conjure" is now the name of a group--including Toussaint; Don Pullen on organ and vocal; slick Leo Nocentelli of the Meters on guitar; Swallow back on bass; Robbie Ameen on drums; Dara on trumpet, vocal and harmonica; Eddie Harris on tenor and vocal, and Murray returning on tenor and vocal, with a number of guest players. Taj Mahal is gone, and so is the friends-getting-together feel of the first Conjure. This is slick uptown funk revue and cabaret music.

"The author reflects on his 35th Birthday" is about doubt in one's fellow man: "If I ever try to bring out the best in folks again / I want somebody to take outside and kick me up and down the sidewalk / Sit me in a corner with a funnel on my head." Pullen's organ dominates with a full-chord wheeze. There is some nice tenor at the end. Individual track credits aren't given, but this is one that sounds as if it has Bobby Womack contributing some of the vocals. "Loup Garou Means Change Into," is livelier, more syncopated, Latin-inflected again. Eddie Harris' vocal (he is credited as composer, so I believe this is who it is) is choked-sounding and mixed too low.

"'Sputin" comes out roaring and never flags. Noncentelli's wiry guitar leads the way, and the vocalist (while again mixed low) adds Wilson-Pickett-level enthusiasm to the proceedings. Still, Reed's words--ostensibly the inspiration for the recording--are difficult to make out (Reed has a Collected Poems available that includes the words to almost all of the works here; my advice is to get it and read along. My advice, come to think of it, is to get all of Reed's work and read it. The music will sound even better with each page turned). "Nobody was There," with music by Dara, is the first really successful track of this second album. Dara scats over washes of organ and twitting guitar, then sings the poem with the feeling for and involvement with the words that the earlier tracks lack--"I saw your spirit sitting in a chair / I turned my head, but nobody was there." His trumpet solo is again a diamond formed under great pressure.

The medley "General Science / Ish / Papa La Bas" begins with an organ drone and some sketchy baritone by Hamiett Bluiett. Then the percussion enters, a brief female vocal, and then a nice piano interlude by Toussaint. Reed then reads a passage from "Cab Calloway." The next, much more musically interesting, section just gets rolling when the organ drone enters again and fades- scatter-shot, and unengaging for it. A nice acapella "prelude" to "Running for the Office of Love" is dryly-miked and breathy. This leads into "My Brothers," a Jim-Smith-style organ-led song, most likely sung by Pullen. This is a highlight: the music has a great old-fashioned swing and Pullen's slightly uncertain voice is the perfect instrument to deliver Reed's words of exasperation about his disrespect at the hands of his friends. After this litany of abuse ("They come up here / And crack the snot- / Nosed sniggle about / My walk my ways my words...") he decides, "I will invite them again / I must like it? / You tell me / Contest ends at midnight." A full-frontal smile with old-school swing.

The full version of "Running for the Office of Love," is nicely fleshed out, with music by Toussaint. But by this time the grafted-on Latin percussion on so many tracks is becoming tiresome. The singer (Clare Bathe? Diahnne Abbott?) holds her own against piano, organ and horns. "Petit Kid Everett," sets a poem about a second-rate boxer: "He just kept coming at ya / Glass chin first," and beat up everybody who tried to help him, but who never gave up. The music is brilliantly minimal, Fernando Saunders' fretless bass and snapping fingers supporting yet another (different) female vocal. Reed next reads excerpts from his ode to "St. Louis Woman," in his usual rapid-fire style. "Bitter Chocklate," is about the place of black men in society: "When they lay somebody off / I'm the first one off the floor / Bitter Chocolate . . . / Veins full of brine / Skin's sweating turpentine. . . ." The piano and organ get in tune with their inner spidery-ways, and the vocalist wails and whispers, even sings the voice of the woman who stole his woman. Spooky-good, blue and convincing--the equal of any classic Chicago blues.

The next-to-last track is "Beware: Don't Listen to this Song." It kicks up a lot of dust, musically, but again the words are hard to hear (in this case, it's the singer's style plus a low mix). The last moments are given over to Reed singing Cab Calloway's "Minnie the Moocher" with a chorus of children. A nice nod to roots and branches. This second collection doesn't have the intimacy or deep blue feeling of the first--slickness is almost everywhere here--but it's a nice companion work and offers some excellent moments.

In his "Neo-HooDoo Manifesto," Reed quotes a woman, Julia Jackson, on the amulets and talismans in her studio:

"I make all my own stuff. It saves money and it's as good. People who has to buy their stuff ain't using their heads."Reed has always used his head. In 2007, he made his own 'stuff' by forming The Ishmael Reed Quintet, and recording a CD of straight-ahead jazz (with a few poetry readings), titled For All We Know.4 Reed plays piano, and the repertoire is standards for the most part, including pieces by Ellington, Coltrane and Davis. His band-mates include Murray on sax, bass clarinet and piano (on one track); Carla Blank on violin; Roger Glenn on flute and Chris Planas on guitar. Some of the tunes here are familiar to almost any jazz fan: Marvin Fisher's "When Sunny Gets Blue," Miles Davis' "Solar," Coltrane's "Naima," even Kenny Dorham's chestnut "Blue Bossa."

"For All We Know," begins with strummed guitar and flute, then Reed enters with gentle block chording. Just under two minutes in, Reed sparkles up the rhythm a bit, as a signal to Murray to play a sax solo. The players perform it mostly right up the middle, in a straight-ahead jazz style, but Murray includes a few phrases that are a declaration that he knows what decade they're living and playing in. Glenn's flute solos takes the musicians back to the very pretty melody. "Blue Bossa" is also played straight, and the sounds of the instruments come through perfectly: you can hear the humanity in the touch and breath and thought of each note. Planas seems to get a bit lost during his solo, but Murray and Glenn are fine. Reed keeps himself in the background here as on most of the first half of the CD.

"You Don't Know What Love Is" is the first track to include Blank's violin, and there is something off about the flute/violin combination as they play the melody. Each player individually sounds fine, but flutes and violins are not natural playmates and the album suffers somewhat as they attempt to join together here. Murray and Blank playing the melody to Fats Waller's "What Did I Do to Be So Black and Blue," on the other hand, sounds just right for the slightly hokey nature of the tune. Planas plays beautifully here; nothing complicated, just a lot of feel, and he's obviously enjoying himself.

The violin sounds very astringent in the opening bars of Ellington's "Come Sunday," as if standing a little part from the tune's spirit, but in later passages warms up. Murray's tone, on the other hand, is deep blue and gorgeous all the way through. No surprises, no pyrotechnics, even a bit of a cliche in how he approaches it, but he plays the classic style masterfully, and so keeps our attention. The same is largely true of Glenn's flute here, as well.

Those who have read much of Reed's work--particularly his essays, with their motto "Writin' is Fightin',"--might not associate the trait "modesty" with him. But when he solos on "Solar," we suddenly realize that this is his first solo outing. He has modestly kept himself in the background, supporting his fellow players up to this point. Blank is also featured, but does her most uncertain playing of the set.

Reed then reads two of his poems over music by Murray: "They Call Me the Prophet of Doom," and "If I'm a Welfare Queen where are my Jewels and Furs?" The poems are funny and outraged, as usual treating all historical epochs as if they were simultaneous, and they are political in the most basic sense in that they are about the concerns of individual people.

"Softly, As in A Morning Sunrise" is dominated more than most by Reed's piano, as he plays the melody and takes the first solo turn. A nicely swinging gem. Murray plays "out" here, and it fits over Reed's comping with no friction at all. Planas sounds completely focused and offers his best solo. Blank kicks off "When Sunny Gets Blue" and sounds comfortable with what she wants to do, and succeeds in doing it very well (I once met Marvin Fisher, the composer, and talked to him about Kenward Elmslie and about Elvis as he drank Lipton soup out of a Styrofoam cup for lunch; he would have loved this). On "Naima," Blank and Glenn succeed in getting the difficult flute and violin combo to soar, moving the melody gently higher, as if in a cradle carried between them. Very, very well done.

The CD ends with Reed reading another of his poems, "Army Nurse," about the psychological devastation of the experience of war on those who have to endure it. This explains the cover photo: rather than a piano or something musical, there is a photograph of fifteen flag-draped coffins in what looks like the hold of an airplane. While this CD celebrates jazz, it also offers a blues vibration for those bruised or finished off by modern life.

FOOTNOTES:

1. This was originally released on vinyl by American Clave. The CD issue is PAND-42135, from PANGEA/I.R.S.

2. Ishmael Reed, ed. 19 Necromancers from Now: An Anthology of Original American Writing for the 1970s (Garden City: Doubleday & Co., 1970). This was later published as a short book, now out of print.

3. Conjure: Cab Calloway Stands in for The Moon. The CD issue is American Clave 1015.

4. Konch Records [No number].