Turning Pitch Into Rhythm

Henry Cowell and the Evolution of the Rhythmicon

by Greg Dixon

(October 2009)

Henry Cowell (1897- 1965) was an American composer who is most widely known for his early piano music featuring tone clusters, dissonant closely spaced chords that he iconoclastically performed with his forearms. His early works are representative of the American ultra-modern movement, which he helped foster along with composers like Charles Ives, Charles Seeger, Ruth Crawford Seeger, and Carl Ruggles. His treatise on music theory and composition -- New Musical Resources,1 first published in 1930 -- is a seminal work that influenced later music in the 20th century and continues to affect the work of composers today.2 Cowell's theories from his treatise were incorporated into a new electronic musical instrument, the Rhythmicon, which represents one of the most innovative early electronic music instruments. This article presents some of the most important aspects of Cowell's treatise and describes how they are related to the Rhythmicon.New Musical Resources primarily focuses on the discussion of rhythm. Cowell's rhythms are based upon ratios of pitch occurring in the harmonic overtone series, the naturally occurring series of tones created from integer multiples of a fundamental frequency. His rhythmic theories evolved from his studies at the University of California with Charles Seeger, who was one of his greatest influences. Cowell wrote, "Charles Seeger is the greatest musical explorer in intellectual fields which America has produced, the greatest experimental musicologist... One could go on indefinitely and not exhaust the number of subjects in which he has been a pioneer."3

Seeger had pioneered an unique idea: that just as the pitch relations of polyphonic music can create harmonic dissonance, polyrhythm (when different types of rhythms occur simultaneously) could be thought of as "rhythmic dissonance." He even specified distinct levels of rhythmic dissonance contained in the broader field of "rhythmic harmony."4 According to Seeger's theory, consonant rhythms are rhythms that can easily subdivide into one another, for instance the snare drum backbeat of a straight-ahead rock n' roll drum pattern against the steady pulsation of the hi-hat. Rhythm was only one aspect of Seeger's theories; he also focused on other non-pitch musical materials and how they can be dissonant, such as dynamics, timbre, and articulation. Seeger incorporated these musical theories into his pedagogy while teaching Cowell and Ruth Crawford and subsequently solidified them into his theoretical treatise, Tradition and Experiment in (the New) Music. Seeger "finalized" the treatise with the help of Ruth Crawford in 1929, but it was not until 1994 that it was published posthumously as part of Seeger's Studies in Musicology II: 1929-1979.5

Henry Cowell systematized and furthered Seeger's ideas of "rhythmic harmony" in New Musical Resources by strictly mapping rhythms to ratios from the harmonic overtone series. Taylor Greer writes in his critical remarks for Tradition and Experiment in (the New) Music that Cowell's "correlation between pitch and non-pitch functions, of course, strongly resembles that of Seeger; Cowell, however, takes it to much greater extremes--as if he were writing a set of compositional variations on an acoustic theme."6

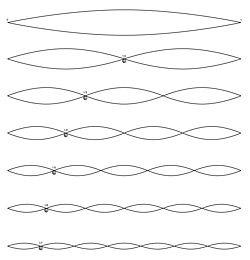

The harmonic series had long been a source of inspiration to musicians due to the nature of its physical relationship to acoustics and resonance. Example 1 shows the harmonic series of a string based upon shortening its length by a half, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth. The frequencies of the harmonic overtones are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency (the first harmonic is the fundamental multiplied by two, the second harmonic is the fundamental multiplied by three, etc.).

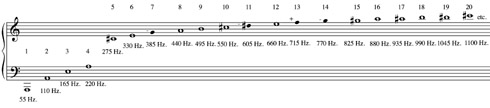

Example 2 shows an expanded overtone series of the note A1 (55 Hz) notated on a grand staff. Musical scales that are constructed from whole number ratios such as the overtone series are considered to be in just intonation. The colored black notes are slightly "out of tune" compared to the equal-tempered tuning system (the system used to tune pianos today so that they can play in all keys) and are signified as flat or sharp in the example by the plus and minus signs. Notice how each harmonic overtone's frequency is 55 Hz higher than the previous harmonic, but the intervals between subsequent harmonics become smaller due to the logarithmic nature of pitch.

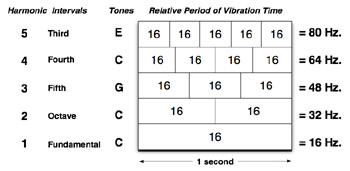

In New Musical Resources, Cowell describes how tones in the harmonic series have vibration speeds that are periodically related. Example 3 shows the first five harmonic partials and the relationships of their number of vibrations in a given space of time. From this diagram, we can see that in the time it takes the fundamental to vibrate at sixteen times in a second (or 16 Hz.), the second harmonic has accomplished two sets of sixteen vibrations for a total of thirty-two vibrations (32 Hz.). The third harmonic contains three sets of sixteen vibrations in the same space of time at 48Hz and with each subsequent overtone there are an additional group of 16 vibrations per second.

Cowell writes in New Musical Resources, "The vibration lengths may thus be thought of as making a sort of pattern, in which the units start at the same instant, separate, and reassemble at a point a fixed distance away; and this they continue to do as long as the tones are sounded together. The reason why the simultaneous tones result in harmony instead of a chaos of sounds is that at regular intervals, the vibrations coincide; and in tones forming a musical interval, the smaller the number of units that must be passed over before that coincidence is re-established, the more consonant is the interval."7

If we apply the same concept of temporal relativity of pitches within the harmonic series to rhythm, we can draw a close comparison between the two mediums. The fundamental frequency of the harmonic series can be equated with the whole note, which as Cowell states in New Musical Resources is "the accepted fundamental unit with which to measure musical time (or duration)."8 It follows that subdivisions of the whole note by integers greater than one (> 1) display a similar pattern to that of the harmonic series. Example 4 shows these patterns polyrhythmically using traditional notation. The half notes are in a rhythm that is twice the speed of the fundamental (whole note) at a ratio of 2:1 and are equated to the second harmonic. The triplet half notes are at a ratio of 3:1 and are correlated to the third harmonic. This process continues and is shown in Example 4 up to the twelfth harmonic where twelve notes sound in the space of one whole note.

Cowell's theories on rhythm were revolutionary in that they gave a strange, new form of rhythmic life to the pitch relationships of the harmonic series, which musical theorists had been exploring at least since the time of Pythagoras. Cowell theorizes that pitch and rhythm have a close connection in that they both share a physical relationship to time. For example, in a tempo of sixty beats per minute, each beat occurs at a frequency of 1 Hz, although this frequency is well below the audible range of human hearing for pitches (around 20 Hz).

Cowell's polyrhythms based upon the overtone series, while easily defined theoretically, are very hard to play accurately even for the most experienced musicians. In New Musical Resources, Cowell states: "An argument against the development of more diversified rhythms might be their difficulty of performance … Some of the rhythms developed through the present acoustical investigation could not be played by any living performer; but these highly engrossing rhythmical complexes could easily be cut on a player piano roll."9 The player piano later became the instrument of choice for composer Conlon Nancarrow, who favored the instrument because it allowed him to develop extremely precise rhythms and rhythmic combinations. Rather than develop his ideas using the player piano, Cowell decided to create a new electromechanical instrument that would produce the polyrhythmic combinations outlined in New Musical Resources. He found his answer through a radical inventor, Leon Theremin, who had been working on creating innovative electronic instruments. Theremin is most famous for his invention of one of the first electronic musical instruments, the aetherophone (or theremin), in 1920.

Cowell and Theremin , worked together from 1930 to 1931 to invent a new electronic instrument, the Rhythmicon. The Rhythmicon made the complex polyrhythmic overtone ratios easily performable through the use of its electronic machinery. The Rhythmicon's various rhythms could be turned on and off through the use of a mechanism similar to a piano keyboard, giving the instrument the ability to be used in live performance. These features make the Rhythmicon one of the first interactive electronic instruments.10

The complex polyrhythms performed by the Rhythmicon are very difficult to notate using our traditional musical noteheads, which are based upon even divisions of the whole note. Cowell developed his own notations for these rhythms using differently shaped noteheads. Their rhythmic values are based on divisions of the whole note by odd values such as thirds, fifths, sevenths, ninths, elevenths, thirteenths, and fifteenths. These notes were called third-notes, fifth-notes, seventh-notes, etc. Cowell considered these notational innovations to be a natural musical development and employed them in his early piano composition, "Fabric," which featured complex polyrhythmic strands. He states in New Musical Resources that, "until we develop further in rhythmic appreciation, only the simpler ratios of the scale will be used."11 These subtle rhythmic variations are difficult to feel or hear, but can be learned with practice.

Each key of the Rhythmicon emitted one note from a harmonic overtone series that then pulsed according to the ratios of the harmonic overtone series at sub-audible frequencies (or rhythms), directly linking pitch and rhythm together in a self-similar relationship. The Rhythmicon, with its percussive-like sounds, can be seen as representing the earliest form of what we now call the "drum machine." With regards to polyrhythms, the Rhythmicon is much more flexible than most modern drum machines, due to its experimental musical intentions.

Cowell wrote two pieces demonstrating the performance potential and compositional usefulness of the Rhythmicon: "Rhythmicana," a concerto for Rhythmicon and orchestra; and Music for Violin and Rhythmicon.12 In addition to its use in composition, the Rhythmicon was a useful tool for ear training and experimentation. Cowell's theories continue to influence the music theorists and composers who have endeavored to create new renditions of the Rhythmicon using computers and audio hardware. These include computer-based digital Rhythmicons like Nick Didkovsky's The Online Rhythmicon (using Java);13 Leland Smith's computer realization of Cowell's "Rhythmicana," along with the subsequent world premiere of the work;14 and David Mooney's "Rhythmicon Sections," a work for "virtual Rhythmicon" in twenty-four sections.15 These computer-based Rhythmicon studies are a tremendous help in furthering the study of Cowell's theories and the instrument.

In conclusion, Cowell and Theremin's Rhythmicon was one of the most innovative early electronic musical instruments, with its creative exploration of complex rhythms and their relativity to the harmonic overtone series. Only three versions of the original Rhythmicon were built by Theremin, and the instrument remains a relic of the past. While there has been a rather large group of enthusiastic do-it-yourself analog theremin builders and this early instrument continues to be a part of the modern musical landscape, unfortunately there are no analog Rhythmicons currently in production. It is encouraging to see that new digital versions of the Rhythmicon exist and more will surely emerge with time, but the full potential of the Rhythmicon remains to be explored. The more we discover about the Rhythmicon, the more completely we can understand the intricacies of Cowell's unique musical vision.

Selected Bibliography

Cowell, Henry. "Charles Seeger." In American Composers on American Music, ed. Henry Cowell. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1962.

Cowell, Henry. New Musical Resources. With notes and an accompanying essay by David Nicholls. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Didkovsky, Nick. "The Online Rythmicon" commissioned by American Public Media. Accessed June, 15, 2008. Available from http://musicmavericks.publicradio.org/rhythmicon

Gann, Kyle. "Subversive Prophet: Henry Cowell as Theorist and Critic." Excerpts from the article published in The Whole World of Music: A Henry Cowell Symposium, David Nicholls, editor (Great Britain: Harwood Academic Press, 1997). Accessed June 15, 2008. Available from http://www.kylegann.com/Cowell.html

Greer, Taylor A. "Critical Remarks." In Seeger Studies in Musicology II: 1929-1979. ed. Ann M. Pescatello. Berkeley/ Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994.

Hicks, Michael. "Cowell's Clusters" The Musical Quarterly 77, No. 3 (Autumn, 1993): 428-458

Hitchcock, H. Wiley. "Henry Cowell's Ostinato Pianissimo." The Musical Quarterly 70, No. 1 (Winter, 1984): 23-44.

Mooney, David. "The Rhythmicon." Accessed June 15, 2008. Available from http://www.city-net.com/~moko/rhome.html

Pescatello, Ann M. "Introduction." In Seeger Studies in Musicology II: 1929-1979. ed. Ann M. Pescatello. Berkeley/ Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994.

Rich, Alan. American Pioneers: Ives to Cage and Beyond. London: Phiadon Press, 2007.

Schedel, Margaret. "Anticipating Interactivity: Henry Cowell and the Rhythmicon." Organised sound: An International Journal of MusicTechnology 7, no.3 (2002): 247-254.

Seeger, Charles. "On Dissonant Counterpoint." Modern Music, 7 (June-July, 1930): 25-31.

Seeger, Charles. Tradition and Experiment in (the New) Music, in Studies in Musicology II: 1929-1979. ed. Ann M. Pescatello. Berkeley/ Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994.

Smith, Leland. "Henry Cowell's Rhythmicana." Anuario Interamericano de Investigacion Musical, 9, (1973): 134-147.

FOOTNOTES:

1 Henry Cowell, New Musical Resources, with notes and an accompanying essay by David Nicholls. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

2 Kyle Gann, "Subversive Prophet: Henry Cowell as Theorist and Critic." Excerpts from the article published in The Whole World of Music: A Henry Cowell Symposium, David Nicholls, editor (Great Britain: Harwood Academic Press, 1997); available from http://www.kylegann.com/Cowell.html; accessed June 15, 2008.

3 Henry Cowell, "Charles Seeger," in American Composers on American Music, ed. Henry Cowell, (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1962), 119-123.

4 Charles Seeger, Tradition and Experiment in (the New) Music in Studies in Musicology II: 1929-1979, ed. Ann M. Pescatello, (Berkeley/ Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994), 131.

5 Ann M. Pescatello, "Introduction," In Seeger Studies in Musicology II: 1929-1979. ed. Ann M. Pescatello, (Berkeley/ Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994), 8.

6 Taylor Greer, "Critical Remarks," in Seeger Studies in Musicology II: 1929-1979, ed. Ann M. Pescatello (Berkeley/ Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994), 37.

7 Henry Cowell, New Musical Resources, with notes and an accompanying essay by David Nicholls, (Great Britain: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 47-48.

8 Ibid., 49.

9 Ibid., 64-65.

10 Margaret Schedel, "Anticipating Interactivity: Henry Cowell and the Rhythmicon," Organised sound: An International Journal of MusicTechnology 7, no.3 (2002): 247-254.

11 Henry Cowell, New Musical Resources, with notes and an accompanying essay by David Nicholls, (Great Britain: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 101-102.

12 Alan Rich, American Pioneers: Ives to Cage and Beyond, (London: Phiadon Press, 2007), 128.

13 Nick Didkovsky, "The Online Rythmicon" commissioned by American Public Media; available from http://musicmavericks.publicradio.org/rhythmicon/; accessed June, 15, 2008.

14 Leland Smith, "Henry Cowell's Rhythmicana," Anuario Interamericano de Investigacion Musical, 9, (1973): 134-147.

15 David Mooney, "The Rhythmicon," available from http://www.city-net.com/~moko/rhome.html; accessed June 15, 2008.