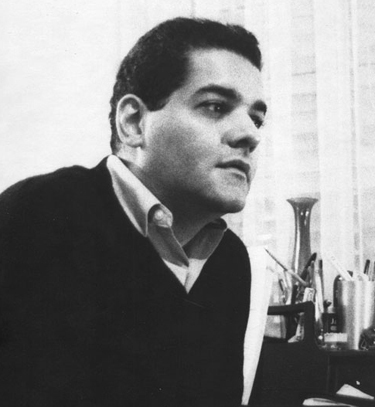

GEORGE RUSSELL

interview by Jason Gross

(April 2014)

Even though he had over two dozen albums to his name, history is going to remember jazz pianist/composer/arranger George Russell for something other than the music that he made. Instead, Russell's 1953 book The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization is what history will remember him for and he knew that. There, Russell made the radical leap in music theory to ditch chords for scales, finding there was a great freedom to this new way of seeing and making music. Later in the decade, his theories led to modal music that Miles Davis and John Coltrane embraced on their own recordings.

Amassing not only a MacArthur Genius grant but also more than one Guggenheim fellowships among his awards, Russell was a restless soul who not only keep his own band going (the Living Time Orchestra) through the 1980's but was also working on a second volume of his book right up to his death on July 27, 2009.

Several years before that, hanks to master jazz scribe Gary Giddins, who was then a columnist and editor at Village Voice, I was lucky enough to get an assignment for the paper's Jazz Supplement to cover Russell and his career. I met up with him at his downtown apartment in January 2003 with his wife Alice in attendance. She warmed me beforehand about doing the interview- ‘you'll have to speak up when you talk to him- he's spent years on bandstands' (indeed, I had to repeat some questions to him, even when sitting next to him). When speaking to Russell himself, he had his own cautionary note for me. ‘I have to apologize for these lapses between thoughts. I got a lot up here,' he said, pointing to his head.

He wasn't kidding either. I tried mightily to keep up with him as he described the genesis of his theory and its development over the years. The second volume of his book was something that he had been working on for years, promising that it would include ‘more examples' of his theory and analyze all types of music with it. He was very proud of the book, keeping a copy there at his side, noting that it was ‘what I had to show for my life' as he pointed to it.

I also couldn't resist asking him about the ‘Lincoln Center incident' in 1992 where they bristled at him using an electric bass in his work for a 70th birthday performance. He called the whole thing ‘frivolous' and noted that he wasn't interesting in articles/publications or the radio. Instead, he said that he just wanted to focus on ‘finding new ideas.'

When I asked him about his legacy, as I wrote in my article, he replied:

"I'd hope that what I've done with the concept would be remembered as my gift. And that it did work. And that I was someone on the side of unity and that I bring music closer to unity."The Voice article came out in June 2003 and Russell told me that he appreciated my piece. While the article only included a handful of quotes from our interview, I wanted to present the full interview itself to let Russell tell the story of his work and career in detail himself.

PSF: If you were to describe your theory to a layman, what would say about it?

GR: You can think of it as this- you're going down the river in a local steamboat. The towns along that river (are) chords. The boat would stop at each chord. The captain would have some melody that caused the genre of the chord to be heard as such. Continuing down the river, that's the way the melody would be received. Each town has its own sound. The captain, let's call him... John Coltrane. (laughs) If you think of his famous solo on "Giant Steps." He's stopping at every chord/town along that river. (He's) playing a melody that centers the listener right on that chord/town. Then to the next one. That's the way he gets down the river. Lester Young got down the river in a faster, express boat. It did not stop at each chord/town. It stopped only at the larger cities. He had to depend more on time. Forward movement, time itself to make that journey. But he would sound a melody for the listener, over a number of chord towns that center on the... might call it the final, to which those chord towns resolve.

PSF: So it's a destination then?

GR: Yes, that's right. Immediately, he's sending a message that these four/five chord/towns are final and he goes down the river, stopping at those larger cities.

PSF: After you work and published this theory, did you see your work as a break from the tradition of bebop?

GR: It doesn't fight anything. What I was looking for is how melody behaves. At first, you might say how it behaves in a jazz sense. Lester Young didn't mind choosing a final chord, a larger chord town in which the smaller towns resolves. Coleman Hawkins represented another school- he was an originator of what I'd call vertical playing. He and Lester were each indicating tonal center. With one, the river was the tonal center, the other was a final chord, a major and minor one.

PSF: So you see the theory as a natural progression of what was happening then?

GR: Well, what was happening, the horizontal way of playing really came out of slavery. Blacks were denied musical instruments. It comes out of church music, which is so prominent these days in commercials. It kind of became a hierarchy and sort of a duel with the vertical way of playing, performed mostly by Coleman Hawkins. The vertical players had a term for the horizontal players- they called it 'shucking.' (laughs) They weren't sounded the genre of each small town along the river. They were only sounding the genre to which those chords ultimately resolved. By that, they automatically had to be playing a melody that would indicate that chord-town over the vertical melodies. So you have the horizontal players who the vertical players said that they didn't go to school but that wasn't true. Lester Young really had both sides down and he used it to show occasionally that he had the chords down.

They were also the supra-roles for certain players and these were people who reached beyond the horizontal and vertical, combined them and actually created what I call 'secondary chords,' like Ornette. He floats down the river. He's just out there! (laughs) He had a huge influence on jazz. Bebop is basically based on all kinds of show tunes. "What Is This Thing Called Love" is actually a horizontal melody. Bebop was a very vertical music for a number of reasons, some not having to do with music.

After World War II, black soldiers came back to find the same old thing, nothing had changed for them. Black intellectuals, which I'm not, didn't go too far up in the educational field. I made the choice to drop school and go it on my own. People kid intellectual people all the time so I laugh when I get called that.

Ornette was the first one to change melody, change rhythm, change form and brought all of that with him and used it in music. In concept terms, he would be a supra-player.

PSF: Do you think your theories affected his work or vice versa?

GR: No, because I started into this whole effort to change music... I personally felt that traditional music was not the explanation of what was right.

PSF: What do you mean by that?

GR: I mean that... with the four modes- Dorian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Phrygian- each one of them had a secondary mode. So the Dorian and the secondary mode started the 4th interval below the authentic mode. The church's modes were what were called the authentic modes. Each authentic mode Dorian had D,E,F,G,A,B,C,D. Its authentic mode, its real mode, began on A, which would be the Aeolian in traditional music theory. Its final was also D. If that's the case and that's the way it was, then the Phrygian would have a scale beginning on C, that's a C major scale. You really need a piano to see this. It's really strange to see the major scale, the Ionian mode, was considered an authentic (odd numbered) mode. It was considered a Plagal mode, which a different final.

Modes or Church Modes are divided into Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, and Mixolydian. Each of those modes have a Plagal mode, a secondary mode, starting a fourth below its final. But also having the authentic modes as its final, meaning that the Plagal mode on C would be CDEFGABC or the major scale as it's called now.

PSF: So your argument with this is that there wasn't unity to it?

GR: Yes, something like that.... I lost my thought there! (laughs) It'll come back to me.

PSF: Approaching these modes, you were looking for unity between chords and scales, right?

GR: Yes, unity was what I was trying to get at. In the 15th century, secular music was becoming more major scale. So the church was running into problems. It didn't want to but it had to include the Ionian mode. They adopted the major scale and then, the major scale became THE scale of music. That was not right because the major scale in music... if you're looking for a scale on which you can build a pyramid, which covers all music, you can't have the major scale. It's not in the overtone series. Lydian is. The mode that made the Lydian scale the F sharp is in the overtone series.

It's very difficult to talk about this or write about it. But it's what I'm doing so I have to go back to fundamentals where I'm writing the 2nd volume now. It's taking me a little time to go back and refresh my memory.

I found that in the Lydian scale, a scale that to my surprise also covered what's called classical music. It's simple. I don't think anyone has approached music that way before. We just accepted the fact that the major scale is THE scale of Western music. It is in terms of its popularity and I'm not arguing against it or trying to kill the major scale. It's an important scale. But it represents the horizontal aspect of music. In other words, it's a duality. CDEF- you play that and F is at the top, the tonic. GABC- C is the top. So it's actually two different chord/towns. In a sharp direction of the piano, it's actually back again to this Plagal mode, this CDEF is the Plagal mode of the C major scale, the first four notes of it. This is as it was in the 15th century.

The Lydian scale is in complete unity with itself. The major is getting there, but not quite there. That's its function. The first four notes of the C major scale, which end on F. It's the horizontal scale of music. It works in a function of time.

PSF: As opposed to the Lydian scale?

GR: The Lydian's function is over in a nanosecond, because it's in unity with chords. First of all, it's in unity with the major chord. The first overtone is C. The first four tones in the F Lydian scale is all white notes (on the piano). To me, that's the birth of tonal gravity. The integral of the fifth supports the entire overtone series.

PSF: As you were working on your own theories, I'm thinking that you must have known about classical composers (i.e. Cage, Stockhausen) that were also working away from major scales, right?

GR: Sure, I know about them and they were searching, like I was. Why were they searching? Because the major scale doesn't do it. The major scale breaks off at a certain point, that's the fourth degree. It's not a unity, it's a duality.

They all were searching and I'm saying that the major scale does not support the whole cosmos of music. I have to say that the Lydian does.

I knew Stockhausen- he got me a Guggenheim. I did a concert with him. They did his symphonic piece for two orchestras. I did a piece with my sextet.

PSF: So you did know about the similar aims of classical composers?

GR: Well, that was taken for granted. The only music I ever studied was from Stephan Volpe. God knows he was out there but we didn't talk about music too much. I knew he was an innovative composer. When I got the opportunity, the impulse... I realized that something happened that was in the way of developing new music.

PSF: That goes back to what you were saying about the major scale?

GR: Yes. You can't build something... There's something wrong with basing a theory, any kind of theory on something that's a duality. You have to have some way to unity as your basis. That's what the concept is about. You have to start with unity- you can't start with duality. Duality is a separate thing. It's on the move, it's connected with time. If I play a C major chord, then I play a Lydian scale, then instantly, it's in unity. If I play a major scale in thirds, a C major chord... it's a very outstanding duality. And another thing is that the Lydian scale eventually includes the major scale.

PSF: After you put out this theory, how did you see that it was picked up by musicians?

GR: The only way I know to answer that question is to say I'm with Miles. We used to get together around 1947 and I asked 'what's your aim?' He said 'I want to learn all the chords.' That didn't make sense to me because I knew something about Miles before he was with Diz and on 52nd Street. I knew, and everyone else knew, that if there's one thing that Miles knew, it was the chords. He knew how to melodize the chords.

So I was in the hospital with Tuberculosis for about 15 months. I had to make a decision- they had given me last rites. I kept dwelling on what Miles said, he wanted to learn all the chords. But my idea was 'how did he really go about that?' First of all, I thought he knew them. Then, I wondered how one would go about this. So I started out with the major chords. While immersing the people in the solarium, as everyone else was sitting around smoking and playing chords, I'm there playing the major scale and the Lydian scale over and over and over. They had a right to do what they did, which was to throw rotten bananas at me! (laughs) I understand, it would drive me nuts too. The major scale... it was something that I had to do. That's where the piano was.

One of the sisters was there and I asked if there was any other piano. There was one in the library. Well of course nobody used the library so it was a wonderful chance to come to this situation, this idea and realize that this was something big. It saved my life.

PSF: What was your intention with this initially once you realized it? To come out with this theory and publish it? It was meant for musicians, to maybe change their way of thinking?

GR: It gets to be esoteric. When I was at the hospital... It didn't make a change right away. You still had people playing essentially vertical. I had to make a decision. I will say that the late John Lewis was the first one to say 'this is really something.' He convinced me of that. I hadn't really studied music. I was a drummer for Benny Carter for a while.

I had to make a decision. In one sense, the Church had to give in to the major scale being the popular scale. But that was a subjective move on their part. It didn't have anything really to do with music. The Lydian scale is a very, very powerful scale, it's very strong. It supports the overtone series and it comes from the overtone series. It's the most natural scale.

So, John helped me make a decision. I thought "this is not meant to be kept a secret. This is something that is objective. It proves that gravity exists in the universe as a force. I can't keep this. I have to let this go." It was a hard decision. But yeah, I did. I think I did the right thing because the situation was that the major scale really didn't work for everybody so they had to develop their own styles. But if you're asking someone, "hey what are you doing, what are you working on?" nobody would give away their secret. I did though!

PSF: So it was published and out there in the world, then what did you see as the fruition of that?

GR: It hadn't finished. It was just beginning. It wasn't something that was finished- I think of it as something that's still evolving.

PSF: When did you see that people were starting to pick up on it though?

GR: I think you have to ask individuals because... I would think that the people who did become influenced by this, like someone would say that he was influenced by the concept. Over the years, Miles would say 'this is the motherfucker who taught me how to write.'

I went to his house one night and he had a note on the door that said 'if you ring this bell, it's war.' He was having a down time, around the '60's maybe. I took the note off the door because... he's Miles. He was pretty hot at the time, rock had come out. He did make a comeback. He got out of music for a while then when he came back, his heart was in it. I went to see him at a show and I went backstage and he gave me a hug.

(Russell went on to recount the story of a Yugoslav dissident who had been prosecuted under Milosavic. He met Russell during a tour of Europe and showed him a copy of a book that was dear to his heart- a Slavic translation of the Lydian concept)

It's hard to say how or who my work influenced because it's a non-stop procedure. In the work I'm doing now, I'm analyzing things like "The Rites of Spring."

PSF: Did you see your theory as advancing jazz in a way that gave it a serious aura that classical music already had?

GR: There's some truth to that. That was another reason I said (to myself) 'you can't keep this in.' You don't work on this for years just to have it for yourself. You have to give it to humanity. You have to share it. You have to make what it says (real). It has a way of saying things. It really speaks of unity. Duality is where you say one thing one way and you also say the opposite.

PSF: You seem to be almost professing this as a religious doctrine. Did you ever see it that way?

GR: Yes. You have to consider the circumstances where it came about. Miles said that he wanted to learn all the changes. I was lying in St. Joseph's Hospital on 143rd and 5th Ave (New York) and I was hemorrhaging, saying to myself 'there's a way out of this other than giving up.' There was 15 guys in the room but I had a corner so I just turned my back and it was all private. I would think and think and think. It saved my life. What I learned from it was that nothing is going to make sense until we have unity.

PSF: How would you characterize your relationship with Miles?

GR: Miles respected me. I think he respected my effort. Obviously, he respected the outcome of my respect. He said I made an influence on him. I was as close a friend as anybody to him. I don't make it a race of that to find out who was closest to Miles. Sometimes I'd just say to him 'come up to the house.' (laughs) But he's never been ashamed of saying that I was an influence (on him).

PSF: What did you think of him personally?

GR: I had the highest regard for him as a creative musician. He satisfies the intellect, he satisfies the emotions, he satisfies the movement. That's what music should be.

PSF: A lot of people see you mostly as a theorist. What do you think about that yourself?

GR: (bristling a bit) No, not totally. I've won various awards. I think that I'm not so well known in America but I wouldn't say that of Europe. My band works all the time in Europe. We did just an Italian festival and in June, we played the Barbican (London) last June. I've been working with the same band for a while- five or six Americans and the rest from Europe- and that makes it nice and easy.

If people see something wrong (in Europe) with an orchestra, they're not afraid to come out and say it. In this country, you're completely ignored. Sometimes the record companies themselves get in the way.

One of my most important pieces, that I consider, is "the African Game." There's a lot of hilarity in there. You have to let it out. You can't keep it in.

PSF: You were part of musical salon of people including Evans, Roach, Miles, Bird where you'd all get together and talk. How would you characterize these get-togethers? What would you talk about with them?

GR: We would talk about women! (laughs) And then maybe music. But what was there to say? You had Bird and Max there. It was music sometimes but it was about music, saying 'we do we go? Where do we go from here?' There was no looking back or sliding back. The whole atmosphere was wonderful. All I know is that somewhere along the line, it ceased to be an adventure and innovative.

PSF: When did you see that happen?

GR: That's a hard one to explain but I think it started... The ‘70's were wonderful. There were some things in rock that I liked. I liked the bass. I liked Aja (Steely Dan). I thought that was a step in the right direction. I liked to dance. (laughs) I liked (Marvin Gaye's) "What's Goin' On." Then around the ‘80's and into the ‘90's, it seemed like there was a downslide.

PSF: Could you talk about when you left the States for Europe for a while in the 60s?

GR: I didn't feel that I fit into what was going on (here). With some players, the music didn't have any kind of law at all or any kind of law.

PSF: You mean free jazz?

GR: If you want to call it that! (laughs) The drummer would play bluh-luh-luh-la-la, bluh-luh-luh-la-la! I said that I don't want to learn music (like this). The concepts taught me that everything in the universe in under a law. Freedom only comes when there are good laws and it's lost when there are flawed, small laws. So I did have the opportunity to go to Europe with an all-star cast.

PSF: When you find was different about musical climate in Europe as opposed to the States?

GR: I found that they really, really knew jazz. Especially at the Golden Circle (club), everyone used to come there. Ornette had played there (recording two albums there).

PSF: So you think the people there respected jazz more?

GR: Well, the first thing that happened was the Swedish Radio Jazz Orchestra got permission to play music- old piece and new pieces. They had a tremendous respect for me and other musicians. In Norway, there was a festival and a young guy comes out who's about 20 years old- he just played... It was Jan Gabarek. It was just beautiful. I just really felt respected there.

PSF: What led you to come back to the States?

GR: America seemed to be searching for its identity. The young people understand that. That generation wanted a change, wanted to do something. Music was an outlet for them. You couldn't stop that. I felt that Scandinavia had given me so much and that I should go home. Changes were going on. That was the Vietnam War. The sextet I had with Gaberek- we recorded in the oldest church in Norway.

PSF: When you came back, you also took up teaching at the New England Conservatory and you've worked there since then. What are you thoughts about your work there?

GR: Well actually Gunther Schuller sent me a telegram (saying) 'We'd like to have you on the staff.' I realized that by that time, the Lydian Concept could not be put down, could not be left. It was saying 'there's more here.' I didn't want to play clubs all over America and do that. I had a steady place to live, a place where I can keep the concept. It ended up with me being there 31 years.

PSF: When you teach there, what do you feel that you get out of it?

GR: Essentially... security. A guaranteed chance to evolve in music. To try different things. I consider this project (points to the book), my number one goal. I work hard at it, on the new work.

PSF: Do you also have a sense of satisfaction of working with students and passing along knowledge?

GR: The students are serious, they've gotten into it. It's something to be proud of. Not only survive. For those who get it and make an effort.

PSF: Could you talk about the time that you took off from playing and composing and performing so that you could write about your theory? Is it because the work is so intensive that you feel that you have to push everything aside?

GR: I do that all the time. I have to. When I was a kid, my biggest question was 'what am I doing here? What am I supposed to do?' (laughs) I always sort of had an inner voice that I used and developed in this concept. If I had a problem, I'd say to myself 'in the morning before 11 o'clock, I'm going to get an answer.' And it happened. I know that sounds extremely esoteric. I have to make choices.

PSF: You've said that you're working on a second volume of your book to explain and expand on your scale theories. When do you think this will be coming out?

GR: Some time! When it's ready. (laughs) The more I'm into it, the less I can tell.

PSF: How did the Living Time Orchestra come together? Could you talk about your work with this band?

GR: I was taking bands to Europe in the ‘80's. It's a good idea for me because I'm not out on the road really. I'm only on the road when there's a show. When we are, we do it style. It's terrific. Alice holds the whole thing together for me. She does. Taking care of the hotels and making sure it's not a drag.

PSF: How do you balance out time between composing, the orchestra and teaching?

GR: Priorities. This takes top priority (points to the book). Actually, a band in the Ellington sense... he had to travel, he had to compose. I don't need to do that.

PSF: So you're there with the band all the time?

GR: Yes, I'm there conducting the band all the time.

PSF: You're just saying that you don't have to do this year-round?

GR: Yes. I'm not committed to playing one night here and another night there. We ended up doing that this summer, doing five nights though.

PSF: How often do you do shows now throughout the year?

GR: A handful but they're usually in close together places. They're very, very important places that we play. We were the first jazz orchestra to play in the place where Stravinsky premiered "The Rites of Spring." We played places like that. The audience expects us to be something else and we expect them to be on another level.

PSF: How would you like to be remembered?

GR: I would hope that it would be in a positive way and with the work that I've always been doing with the concept.

See the George Russell website