EAST AUSTIN JUKIN'

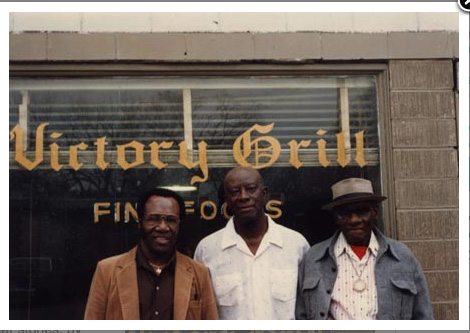

photo by Tary Owens

The Preservation of the Victory Grill

By Johnny Meyers

(December 2015)

ED NOTE: Jonny Meyers is a New Yorker who happened to spend several years in Austin, fronting the ska-addled group the Stingers and then RokkaTone before heading back to Queens to become a music teacher. Meyers also did his master's thesis at University of Austin in 2007 about the small clubs in the East Austin area. Of course we were intrigued when we found out about this, running into him on a trip back from SXSW. Meyers was nice enough to share his thesis with us, which focuses on the Victory Grill club, and we present a three excepts from "Black Music Spaces and Subjectivity Formation: The Legacy of the Chitlin' Circuit, Juke Joints, and the Preservation of The Victory Grill." See more about Meyer's work at his website.

BACKGROUND HISTORY AND CURRENT CONTEXT SURROUNDING THE VICTORY GRILL

Johnny Holmes, a black entrepreneur, built the original Victory Cafe in 1945, on East 11th Street, in Austin, Texas. According to Lindsey, the Victory (as it is commonly called) was originally an icehouse that served beer and informally provided blues music on the patio. Eventually Holmes expanded the Victory and, in 1948, built the structure that still stands on 11th Street today, changing its name slightly to The Victory Grill. No longer a mere icehouse, this eatery and music venue developed into one of the many juke joints that lined Austin's East 11th and 12th Streets. By 1956, when Holmes added a much larger back room, known as the Kovak Theater, the east Austin blues scene was thriving.1 The Victory Grill, along with other juke joints, such as Sam's Showcase, The I.L. Club and Charlie's Playhouse, helped Austin become an important stop on the Chitlin' Circuit in Texas. Photographic evidence, oral histories and limited, yet valuable hard archives validate the presence of legendary blues artists such as Bobby 'Blue' Bland, B.B. King, Big Joe Williams, and Billie Holiday at the Victory. In addition, the Victory was home to many of the local Austin blues artists, such as T.D. Bell, Roosevelt T. "Grey Ghost" Williams, Erbie Bowser. Major Burkes, Hosea Hargrove and Blues Boy Hubbard who made their living performing along the East 11th and 12th Street strip.

During the 1950's and 1960's, segregation in Austin confined black people, and as a result black commerce, to the east side (east of the main highway, I-35), which ironically allowed for the music scene to thrive. Eventually white university students from the University of Texas and other neighboring schools made their way to the east side, contributing even more to the growth of the scene. However, when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended legal segregation and, more importantly, the Fair Housing Act of 1968 allowed middle and upper class blacks to leave the neighborhood, the scene changed. Touring acts that once played places on the east side like the Doris Miller Auditorium (the most popular acts) or juke joints like The Victory Grill, now played auditoriums and large venues on Austin's west side, such as Antone's, which gave birth to the well-known music scene of 6th Street that spawned world famous blues acts like the Fabulous Thunderbirds and Stevie Ray Vaughan. Eventually, as the east side began to suffer an incredible loss of commerce, even local black acts moved over to the west side in search of better paying gigs, and, one by one, the juke joints disappeared. By the mid-1970's, The Victory Grill was one of the last east Austin juke joints still standing.

From the 1970's until recent years, The Victory Grill had not been able to operate with any measure of consistency. It has gone through brief periods of openings and even longer periods of closure. Indeed, at some point, the venue was completely closed for eight to nine years and was inhabited by a homeless man who watched over the place.2 Through the 1980's and into the 1990's, there had been numerous changes in management. Moreover, the club suffered physical damage due to the lack of income and a 1988 fire that nearly destroyed the venue for good. However, through all of this, Johnny Holmes and family retained ownership of the physical site. He refused to tear it down or sell the property to buyers who were looking to invest in the neighborhood for industrial purposes. Music returned, with some consistency, to the Victory in the 1980's and 1990's when independent producers such as Tary Owens (folklorist, musician) and Harold McMilllan (non-profit arts entrepreneur and founder/director of Diverse Arts Production Group) brought local east Austin blues musicians and various touring acts back to the Victory. After the fire, a series of benefits also brought some reconstruction money and events to the club, but this was short lived. In the past few years, the Victory has survived by hosting sporadic events and renting out the venue for various independent productions.

Today, The Victory Grill still stands at its original location on 11th Street mainly due to the tireless, political efforts of its current proprietor, and my main informant, Eva Lindsey. In 1997, before the passing of Johnny Holmes (February 2001), Lindsey came to The Victory Grill, and, with great foresight and an interest in historical preservation, worked to get the Victory recognized by the National Registry of Historic Places (part of the U.S. Department of the Interior) as a member of the Chitlin' Circuit. Since then, the Victory has passed through several phases of reconstruction. According to McMillan, the earliest phase began when Lindsey came to The Victory Grill as booking agent, artist relations and manager and partnered with R.V. Adams, a "fix it guy" and friend of Johnny Holmes. Diverse Arts became the main programming agent at the Victory, booking four nights a week of blues and jazz shows, providing sound equipment and promotional services. Together, the three parties attempted to open the Victory as a full time music venue. Eventually, relations between the parties turned bad and Adams asked both Lindsey and McMillan to leave. Frustrated with Adams, Lindsey and McMillan agreed and Adams ran the venue for three more years, which McMillan described as a time when "the house was often dark," in reference to the fact that there were hardly any shows being programmed and little clientele (McMillan, personal communication 1).

After Adams left, Lindsey returned and continued to book events at the venue, along with McMillan and Diverse Arts, but not as frequently as in the previous period. Though this phase could be characterized by several factors, the most important is the attempt to build political relationships. Following Holmes's death, Lindsey decided to continue on a city, state and federally sponsored securing and restoration of the physical site. In 2004, she helped secure state recognition for the Victory as a "Texas Treasure" by "Preservation Texas" in 2004. In 2005, she established the "Friends of The Victory Grill," and non-profit 501c3 organization made up of a board of directors put in place to work on fundraising. 3 Recently, Lindsey secured city recognition by receiving historic . zoning status in 2006, which will eventually lead to the designation of The Victory Grill as an Austin city landmark. The other characteristics of this phase include bookings of events that are self-produced and self-staffed, the presence of volunteer staffing, lack of a formal/active infrastructure, changeover of personnel, and a reliance on pro-bono work by outside contributors. On the other hand, in comparison to the previous decades, there is an increased urgency on the political end and a slightly increased level of consistency due to the long-term presence of the venue's current operations manager, Clifford Gillard, who is also the producer of its most consistent event, the Capitol City Rapfest.

The context of the surrounding neighborhood is equally important to the Victory's history. Over time, the neighborhood has undergone tremendous economic, demographic and cultural change. The first of which happened at the outset of integration laws such as the Fair Housing Act, when black middle class families moved out of the neighborhood (discussed in previous chapters). Then, in the 1970's, federally subsidized projects of Urban Renewal, which advocated "slum clearance" under the auspices of improving the lives of the urban poor population, began the bulldozing of inner city neighborhoods across the country (Lipsitz 1998, 6). The promise of affordable housing worked in conjunction with the construction of highways connecting the suburb to the city and aid in the development of the suburban infrastructure (water and sewage). When the rubble cleared, much of the areas destroyed were replaced by "commercial, industrial and municipal projects," and while a disproportionate number of inner city whites had taken flight to the suburbs, the promise of affordable housing rarely took form (Lipsitz 1998, 7). In addition, new real estate laws under this same program allowed private buyers and lenders to escape housing regulations, creating the rise of the inner-city slumlord. Color- blind integration laws removed race from the language of the law, which unfortunately resulted in a reverse effect; rather than promoting equality, these new laws protected racially exclusive practices of real estate, such as the inaccessibility to federal or private housing loans for minorities, by making race a non-issue. In other words, integration laws ignored the fact that blacks had been denied access to the means of property ownership for many years before the civil rights amendments, and therefore could not afford property in the suburbs without provisions that took race and history into account. Urban Renewal, in the end, created a massive white flight from the city while, at the same time, paving the way for access to industry at the expense of inner-city blacks and minorities. It helped create slums out of once vibrant neighborhoods and also continued to keep middle to lower class blacks from ownership of property. East Austin's black neighborhood, and especially the East 11th Street juke joints, was deeply affected by Fair Housing and Urban Renewal. The great paradox of integration and its affects on black music is summarized well by Nelson George when he writes, "while the drive behind the movement for social change was the greatest inspiration for the music, the very success of the movement spelled the end of the R&B world" (George 1998, XIV). This is easily applicable to the "death" of the music scene on East 11th Street and the subsequent period of lengthy closings of The Victory Grill. In an interview with Byron Marshall, the president of the Austin Revitalization Authority (ARA), a non-profit organization created to bring about a rebirth of a portion of east Austin and specifically the 11th and 12th Street area, we discussed the side effects of integration specific to East Austin:

Marshall: I think through open housing, or the "Fair Housing Act," which is basically open housing and African Americans can live anywhere in the city, that began to change the nature of this community, in that those people who were well to do, who could move, be it home owners, school teachers, college professors began to move out.Marshall's synopsis of what happened to the neighborhood after segregation ties the federal processes of Fair Housing and Urban Renewal to the local, and subsequently to The Victory Grill. The time period in which East 11th Street saw an influx of drugs and slumlords coincides with the eight-year closing of the venue. Therefore, a closer look at the history of the venue (musical spaces) provides a tangible resource for the political context of the time and to the very effects that federal processes had on the "end of the R&B world" (George 1988, XIV).As they began to move out (the more middle class and upper middle class folks moved out), then you ended up with more renters in the neighborhood. And as you had more renters, you had absentee landlords, property started going down, and the advent of drugs and the neighborhood just started going down…so by the 70's and 80's, 11th Street really wasn't a nice place to be. People were afraid to come here (Marshall, personal communication).

The processes and laws of the '60's, '70's and '80's paved the way for the gentrification process that began in the late 90's and continues in east Austin today. McMillan discussed the move from Urban Renewal to gentrification in east Austin: 4

Interviewer: Explain the process of gentrification here in Ausitn because Gentrification is a little bit different everywhere.During the time of my ethnography there has been an increase in commerce and business investment along East 11th Street, and many young, mostly white, homebuyers have moved into the surrounding neighborhood. Oddly, a few rock-n-roll bars have opened on the east side and there is a growing, white hipster scene as well (one is across the street from the Victory called the Longbranch Inn, named after a former juke joint that existed in its spot before). However, what we see in the excerpt above is that these changes incur the expense of black flight from the neighborhood caused by the systematic (protected by law) rise in property taxes made possible by the results of urban renewal programs of the 1970's.McMillan: It's a little bit different everywhere but, the definition fits and is fairly universal as something that happens in many major American cities. What happens is that there is a neighborhood that is economically depressed. Many times that neighborhood is a non-anglo, ethnic neighborhood. Many times, but not all the time. So you've got a neihborhood that has an ethnic and cultural history and part of what is tied to that is poverty. Most times, at least like in Austin, it is right next to downtown – it is an extension of downtown, so for years it is just fine for this neighborhood to be depressed and not have access to commercial and government opportunities that other neighborhoods have access to because it is primarily black folks who are poor. They don't have a lot of money, don't have a lot of political clout. There is not a lot of high dollar development because it is a depressed community, you know. There's not a bunch of people with a lot disposable income for very expensive houses or very expensive stores or those kind of services. Over time, the city runs out of available downtown neighborhoods to take over for economic development and generally the precursor to this is forward thinking and opportunistic people see what is going on years in advance and they go into this depressed neighborhood and they start buying up property. They might keep it as rental property where they have cash flow or just let it sit there. A lot of times they will just let it sit if it has a building on it and board it up, because one of the things that is tied to federal assistance for neighborhoods to rebuild is a federal definition of slum and blithe, so in order to get this HUD money for economic revitalization and affordable housing and infrastructure improvements and those kind of things there has to be a study that happens that shows the federal government that "yup we got ourselves a depressed area that is characteristic of slum and blithe" because that qualifies you to then get funds to get public investment in the area. Because if public investment starts to happen it then becomes obvious to commercial investment that 'OK, we've got something moving there' – so those people that have been sitting on their land and paying low taxes on it – they now see an opportunity to raise the price on their property as the property taxes and just as the land value goes up because where there once was a vacant lot, there's now a 15 million dollar office building. If you own the lot next door that you bought for a nickel, it's now worth a lot more than a nickel.

Interviewer: Then what happens, what is the process for the person who owns that lot. Are they pressured to sell it?

McMillan: They are pressured to sell it. If they have cash, if it is a development opportunity for them. If they are not of that mindset, it is an attractive way to leave the neighborhood that has been labeled with evidence of slum and blithe. If you are poor and you have the property and you hang onto it but can't afford to develop it, then your property taxes are going to rise and rise and rise and you might not want to keep up with the property taxes. If somebody offers you $100,000 for the piece of property then that buys you a ticket out of the neighborhood and you might not want to live in the neighborhood anymore. Chances are that if you are going to get offered $100,000 for that piece of property by the developer that wants to help you move out of the neighborhood, he or she are doing that because they see in the near future or in the slightly distant future that $100,000 is an investment that will be returned to them multi-fold (McMillan, personal communication 1).

Despite the changes in the neighborhood and numerous offers to buy out the important real estate/commercial space that the Victory now occupies, a combination of stubborn family ownership and political maneuvering has protected the venue from being torn down or sold to investors. Thus, the significance of Lindsey's negotiations with the state stands at the center of the struggle of the remaining African American institutions of the surrounding neighborhood:

It's the poster child! It's the poster child of what's good and what's bad; what's good if it works. If it doesn't work it will become, especially as a political football, it will become another of those reasons that it seems to be that there is lots of evidence out there that this [Austin] is not a hospitable place (McMillan, personal communication 3).The gentrification process happening around The Victory Grill carries enormous social, cultural and political contexts and contextual changes, too many to cover in this report alone. Nevertheless, gentrification is central to the case study and I explore it further in the description and analyses of this chapter. In what follows, I will show how pieces of the juke joint aesthetic are enacted today as methods of survival within, or in some cases in resistance to, the changing contexts of the neighborhood.

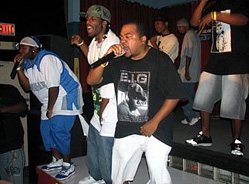

photo by Tary Owens

In 2006 and 2007, I began to focus more on my own observations as a participant- observer at events involving the Victory. Through these observations, I was able to witness some of the business and performance practices at The Victory Grill that could also be measured against the guidelines for cultural properties and historical status eligibility. They also display the practice of traditional survival tactics passed down from juke joint history. The events I observed that provided the information for the following synopsis include the VICE and Four Square records showcases (2006 South by Southwest Conference – mostly young, white, rock/electronic music crowd), the L.C. Anderson High School reunion (older, black neighborhood crowd – Mel Davis's Blues Specialists performing), various blues shows, a Tango Milonga (Tango dance group and lessons – mostly white, Latino/a crowd), a Victory Grill 60th birthday celebration (mixed crowd, blues music, local politicians in attendance), a book signing/reception for All Over the Map, by local writer Michael Corcoran (mixed crowd, blues and gospel music) and most importantly, the Capitol City Rapfest (mostly young black crowd, hip hop/rap music). 5

As I mentioned previously, for the past ten years or so, the main source of income at The Victory Grill has been the renting out of the venue for self-produced events. Since the Victory lacks a paid staff, these events are either staffed by the group producing the event, or by volunteers, performers bartering for use of the venue, friends of Lindsey, or members of the community who are being paid for the night's work on a temporary basis. Modes of informal economy are still at use. Everything is still cash business, from the ordering of drinks and food, to the purchasing of alcohol and supplies before the event (mostly on the day of the event), to ticket sales and entrance fees, etc. Preparations for the events are often last minute, as equipment and supplies are often gathered through a range of community resources available through both personal and informal business agreements. A chain of command in regards to staff is not evident – any member can be assigned to work the door, the bar, the kitchen, or sound equipment if they choose or have the skill to do so; there is no preset division of labor. Some events are actually staffed by the group producing the event.6 The demographics of each event range from being predominantly black to predominantly white depending on the nature of the show. Some shows were tied into the Victory's history and presence in the neighborhood (blues shows, neighborhood reunions/private parties, political rallies) while others were not (rock-n-roll record label showcases at the South by Southwest conference, university ensemble performances).

The club's ability to reinvent itself from event to event is another example of the mobility of the juke joint aesthetic at work. It is a tactic of survival that protects The Victory Grill by making it move covertly with the rapidly changing neighborhood; it is not completely resistant to gentrification, yet it still maintains a timeless aesthetic in terms of actual business practices. The renting of the venue allows several things. First, it allows Lindsey to earn an income necessary to pay the bills she has inherited in the informal agreement of club management that she made with the Holmes family. Second, it forges multiple relationships with the new community, while maintaining working relationships with the traditional community. Also, it protects the physical structure by making it active. 7 Finally, it gives an avenue for informal modes of economy and veil passage (as seen in the ability to accommodate demographic change, much like the case of Charlie's Playhouse in the 1960's) to continue at The Victory Grill. 8

The most significant event in terms of this study is the ongoing Capitol City Rapfest. For the past two years, it has been the most stable, regularly attended and longest running event at The Victory Grill. As I mentioned in the previous chapter, the Rapfest is a monthly (sometimes bi-monthly) showcase that gives local rap groups, solo rappers, DJs and even a young comedian a space to perform their original work. The Rapfest is the brainchild of Gillard, a concessions salesman and black youth advocate who moved to Austin from Trinidad and attended the University of Texas at Austin, and Leon Oneal, a college student in Kinesiology at Houston- Tillotson University (a historic black university in east Austin) and local DJ, known as DJ Hella Yella. According to both Gillard and Oneal, the Rapfest at The Victory Grill began as a result of Sunday gatherings in the summer of 2005 at Gibbins Park, where DJs and rappers performed by Gillard's concession stand. When the summer ended, Gillard and Oneal set out to find a proper venue to rent for a one-night performance. Unaware of the Victory's history, Gillard walked into the venue and inquired about renting it for one night. The first show was held in September of 2005. After Lindsey explained both the history and the availability of the venue, Gillard forged a working relationship with Lindsey and began trading his concession and venue management services in order to secure a regular space for the Capitol City Rapfest. According to an interview taken with Gillard and Oneal on March 29, 2007, he called it a "perfect fit" (Gillard, interview, Austin, 03/29/2007). The following analysis of the Rapfest comes from excerpts from that interview and field notes of the two Rapfest performances I observed prior to the interview. Both will address how current black performance practices held at this juke joint face harsh conditions similar to the conditions of the past and how they too invoke the four aspects of the juke joint aesthetic.

MOBILITY

I begin with aspects of mobility as described in chapter two. When I asked Gillard and Oneal about the business practices involved in the promotion, booking, staffing and production of a Rapfest show, they revealed characteristics of continuum. For instance, when talking about how a Rapfest staff is put together, they claimed:

Oneal: We kind of like drew straws between the DJs. Sometimes you'd be working the bar, the front door.The use of the term "underground" brings the covertness of the space to the forefront. Covertness in Black Public Spaces, as discussed in this paper and in regards to Mark Anthony Neal's work, is a result of identity in motion – the ability to step in and out of two worlds. In this case, identities between the members of the Rapfest are non- static. Roles are shared at random. The line between performer and venue staff is not clearly drawn. Relationships are multiple and mobile when the production takes on an "underground" aesthetic. This way of doing business was also seen in the practices of the "hustle" described as part of juke joint history. They are not, however, the same, because the contexts have shifted. Still, there is a continuum, or changing same, because what the shifts have in common is that they continue to make conditions harsh for African Americans.Gillard: Right (laughing). Understand that we are dealing with underground ways of doing things. We have to make it work whichever way it does (Gillard/Oneal, personal communication).

A changing same can be seen in the view of juke joints as safe places. During segregation, jukes were regarded as safe places from a white world that was outwardly exclusive and violent. Now, as exclusion has become harder to recognize (as in the adverse effects of integration, color-blind law, urban renewal and gentrification), blacks must form more complicated strategies of passage. The sentiment of juke joints as safe places can be seen in Gillard's description of a "comfortable" place when talking about what he sees happening to the neighborhood and the role of The Victory Grill in that change:

Gillard: The neighborhood itself is changing and to be able to maintain a legacy here in the middle of the most drastic change you can get – that in itself will tell a story.In this excerpt, we see both similarities and differences to the historical ideas of juke joints. The maintenance of covert spaces is echoed in Gillard's comments. Juke joints have always provided a sense of comfort in that within the space, veil passage was free flowing and escape from the outside (white) world was possible. However, gentrification has created a brand new context and, subsequently, the appropriate tactics for the maintenance of covertness has changed. Whereas the juke joints of yesterday faced middle to upper class black flight, the juke joints of today face the influx of whites that will change the demographic and cultural make up of the surrounding neighborhood. Therefore, according to Gillard, it is quite urgent not only to keep The Victory Grill from being torn down, but also to keep it as a space for black cultural expression and black business ownership.Interviewer: I want you to expand on that. How is the neighborhood changing and what does this program mean with that?

Gillard: This is as real as I can say it – you know what I mean. I think that ten years from now, this particular neighborhood is going to be solidly white. And although this is my adopted history, I think people would enjoy saying 'guess what, even though it is white, there is a spot there that has been black owned, black run for one hundred years, and we can go there and be comfortable…' that we can go up in there anytime we want. It makes a realization that even though things change, they probably will stay the same (Gillard/Oneal, personal communication).

Later in the interview, Gillard expanded on certain survival tactics that are appropriate for this phase of The Victory Grill's history: the main one being the ability to negotiate with the state for official landmark designation. When asked about the presence of Rapfest members at the Austin City Council meeting, Gillard responded as follows:

Gillard: How to get those people [Rapfest youth] and others to realize that what they did that day was so significant, that if they continue that process by either learning the system, being able to work in the system, use the system to their advantage – I don't know how we are going to do that, but it certainly lends to the premise that if you get an opportunity and you understand what that opportunity is, you can probably take advantage of it for betterment…the unknown is a scary thing (Gillard/Oneal, personal communication).The act of maintaining The Victory Grill as a covert black space coupled with the recognition of the need to learn about and eventually negotiate with state processes of historic recognition is an example of the modern day workings of black mobility. A complex continuum of mobility and passage still exists, as long as conditions for black youth in America remain harsh (maybe even harsher than before). However, with the addition of the state, and the new context of gentrification, the players and the playing field have altered, and the tactics must adapt accordingly. Mobility is a given, while the new contexts make up the "unknown" that must be dealt with.

FOOTNOTES

1. According to an interview with Lindsey, Holmes named the Kovak Theatre after a venue called the "Kovak Theatre" in Alaska, where Holmes lived for some time.

2. From Lindsey, personal communication 4.

3. See www.historicvictorygrill.org - This organization is the managing and fundraising arm of the Historic Victory Grill's preservation and renovation project. In an effort to preserve the history and musical culture of The Victory Grill and surrounding neighborhood, the Friends of The Victory Grill have embarked on a mission to raise money to restore the building to its original structure. The Friends of The Victory Grill intend to provide educational and public programming to public schools, universities, patrons and tourists. The curriculum will address the history of jazz and rhythm and blues music, the segregated south, the cultural significance of the "Chitlin' Circuit," and the importance of keeping African American historical places preserved for future generations. ED NOTE: the site is no longer active but you can see the Victory Grill's Facebook page and this page for the Grill at the Texas State Historical Association

4. The full excerpt is included because it relates directly to the two events that this chapter will focus on.

5. Micheal Corcoran is a music critic and writer for the Austin American Statesman. His most recent book, All Over the Map: True Heroes of Texas Music was published by University of Texas Press in 2005.

6. They often provide sound equipment and sound engineer, stage manager, door person, and clean up/wait staff.

7. In an interview on August 7, 2006, Lindsey notified me that the city was set to demolish The Victory Grill during a time when the place looked boarded up and abandoned.

8. A more in-depth analysis of each event would add valuable insights to these claims, but I am restricted by the length requirements of this report.

PERSONAL COMMUNICATIONS:

- Gillard, Clifford & Leon Oneal. Personal communication. Austin, Texas. March 29, 2007.

- Lindsey, Eva. Personal communication 1. Austin, Texas. March 1, 2005.

- McMillan, Harold. Personal communication 3. Austin, Texas. March 31, 2005.

SOURCES:

- George, Nelson. 1988. The Death of Rhythm & Blues. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Lipsitz, George. 1998. The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit From Identity Politics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.