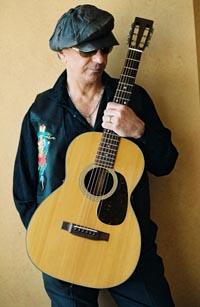

Dion

Photo © Bill Bush 2005

'The Wanderer' Settles Down With the Blues

by Keith Walsh

(February 2007)

As one of only a handful of rock artists still making music after six decades, and as someone who was in the delivery room to witness the birth of rock and roll, Dion is well acquainted with the genre's parents: country music and the blues.It should come as no surprise then, that his most recent offering is a CD of blues standards called Bronx In Blue, proving that the former teen idol--whose output runs the gamut from doo-wop, to R&B, to rock, folk, and now blues--still has what it takes to record an album that reaches out of your speakers and grabs you by the ears. A casual listener might think a blues collection is a departure for the artist known for classics like "Teenager In Love," "The Wanderer," "Runaround Sue," and "Abraham, Martin and John," but nothing could be further from the truth.

"It's funny," he told me in an October 2006 telephone interview, "it's almost like what I've done (before) was a departure from who I am, you know. It's a funny bit, because when I recorded this album, they were songs that were (always) in my head. Ever since my pre-teens, I've been listening to some of this stuff. They've always been in my head and kind of in my guitar, and I never thought of recording this group of songs."

That all changed as a result of an interview in 2000 with National Public Radio's Terry Gross (available here) during which the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer was demonstrating rock's kinship with the blues. "I was punctuating the hour interview with songs I grew up with," Dion said. "So being I had the guitar there, I showed her what my songs came out of, and the cause for me doing a 'Ruby Baby' or 'The Wanderer.'"

Dion's friends had been on him to record a blues album for years. "Because they heard me singing in the back," he said, "you know, in the dressing room, or at the hotel, or at a friend's house. They know what I'm about." After hearing the NPR interview, Richard Gotterher (who runs the Orchard label) joined the chorus—and music fans everywhere are glad he did. Dion's approach to the blues is a minimal one, with very few overdubs, and features percussion by Bob Guertin and Dion's foot stomping (a blues tradition also found on 1963's "Ruby Baby"). Of Guertin's contribution, Dion says, "He used some shakers and cans, sometimes to sound a little more raw, or a little different. He didn't use an American set of drums—sometimes he used some (percussion) boxes." This pared-down approach reveals the soulful, often primal nature of the blues on tunes ranging from Son House's "Walking Blues" to Bo Diddley's "Who Do You Love," which features an amazing guitar performance by Dion that has listeners scratching their heads, wondering how he did it.

His secret: he's had decades to hone his guitar-playing skills. "There's only one guitar on there," he said. "That's one of the songs that I didn't do any overdubs. It's the only track where I played a bigger guitar, because I wanted it to be percussive, and I wanted it to have some sustain."

That guitar is the Dion Signature Edition Model, produced by Martin for a limited release starting in 2002. The use of a Martin is a natural for Dion, who has used Martin guitars on recordings as early as "Ruby Baby," including a D-18, a D-28 and several D-35s. His current axe is a SP-000C-16E.

'Rock and Roll in Its Infancy'

And though Dion is famous first for his voice and songwriting, his affinity for the guitar has been a guiding force since the beginning. "I started out with the guitar, with all of those blues and country tunes, and then when I got a record contract, they wanted to put me with this lame group, this vocal group that was so white bread, and I went back to my neighborhood and I recruited a bunch of guys—three guys, and we called ourselves Dion and the Belmonts."

"I'd give 'em parts and stuff," Dion said of the Belmonts. "I'd give 'em sounds. But back then it was wide open, we didn't have too many role models. Because rock and roll was in its infancy, and you could do anything, could make any sounds you want. So that's what 'I Wonder Why' was about, if you ever hear that song. We kind of invented this percussive rhythmic sound."

"The first time when I put those guys together, and we went to my house, and put together 'I Wonder Why,' that was a defining moment in my life," he said. "To be in the middle of that sound as a sixteen-year-old, I was in heaven. Probably I was sixteen going on seventeen. It was like that was a defining moment in my life. Because if you listen to that song, everybody was doing something different. There's four guys, one guy was doing a bass, I was singing lead, one guy's going 'ooh wah ooh', and another guy's doing a tenor part. It was totally amazing. And when I listen to it, often times what I'm thinking of is, 'Man, those kids are talented.'"

'The Guitar Took the Fore'

Ever the rock and roll rebel, Dion refused to let the record label call the shots with the Belmonts. "I got bored with it quickly," he said, "because the way we were going, it's just way out there, I couldn't understand it. The company wanted to bring me back into those standards that my father would listen to. So I said, guys, I can't do this. I can't do it. I gotta play my guitar. So we split up and I did 'The Wanderer' and 'Runaround Sue' (and) 'Ruby Baby.' I was more into the guitar—the guitar took the fore."

The instrument is quite prominent on Bronx in Blue. In addition to Robert Johnson's "Terraplane Blues" and Blind Willie McTell's "Statesboro Blues," other songs on the album include Howlin' Wolf's "Built for Comfort" and Hank William's "Honky Tonk Blues." Dion first heard Hank Williams as an eleven-year old kid growing up in the Bronx and within a couple of years had just about every Williams recording available at the time. "That's the stuff I grew up with," he said. "You know, I grew up listening to this country station that came out of Newark, New Jersey."

Not surprisingly, county- and blues-tinged tunes are still a regular staple of Dion's musical diet, along with the music of some of his contemporaries. "I always listen to Van Morrison, I like Sheryl Crow," he said. "I listen to a lot of old blues stuff these days. Because I don't know, I started to go back. I started to really go back to some of the stuff I grew up with. I used to go forward and listen to the new bands." Of course, it's no coincidence that's immersed in the blues now, considering that in addition to Bronx in Blue, Dion is putting finishing touches on a second blues album, which he agreed could be considered a "Bronx in Blue 2."

Every song on the album is a gem, including a Dion original called "I Let My Baby Do That," which puts a twist on the blues by leaving out the minor key. "Rock and roll is exactly what you said, it's like taking the blues and turning it into a major key," he said. "That's what Chuck Berry was doing, that's what Little Richard, and Fats Domino--that's what was rock and roll. You take blues, you take country—you had rock and roll."

A Narrow Escape

Though Bronx in Blue features faithful, soulful interpretations that are true to the originals, one liberty taken is the addition of new lyrics to a handful of songs, including an explicitly Christian verse to the Robert Johnson classic "Crossroads." "I tried to explore the spiritual angle of that," he said, "because of the first line: 'I went down to the crossroads, and fell down on my knees. I asked the Lord above have mercy, save poor Bob if you please.'" Dion is no stranger to redemption himself, having successfully navigated his way through some tough times (chronicled beautifully in the songs "Daddy Rollin'" and "Your Own Backyard"), and with divine assistance only narrowly avoided becoming a casualty of the rock and roll lifestyle (not to mention an accidental casualty- more later on his fateful tour with Buddy Holly).

"There's so many artists that I know that died very broken," he said "They never get their own message... 'cause rock and roll is full of guys, that, you know we pride ourselves on the truth and freedom, but some of us never get the very message we're trying to put out. What happened, is I became conscious of that…because in 1968 I was at a very bleak, restless period in my life, the bleakest, darkest emotional, period in my life. I just said a prayer, I went back to the church I grew up in, I got on my knees and said a prayer. I've never been the same since." As a result, Dion cast off his addictions to drugs and alcohol and has been clean and sober ever since.

Early on, Dion says he became aware of a divine influence in his life, most notably in 1959, when he narrowly escaped death by giving up his seat on the ill-fated four-passenger plane that crashed and claimed the lives of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper. "I kind of, they were flipping a coin, and... I gave the seat to Ritchie, because he was so sick. He was a young kid from the barrio, the San Fernando Valley, and he was never in the cold," Dion recalls. "He didn't even go out and buy an overcoat, he sent home for it, and his family put it in a cardboard box, and he received a coat from his parents. He was so sick he was sneezing, and dribbling--and I just said 'why don't you go--you could be in a warm bed tonight.'" As many music fans know, Valens never made it to a warm bed, and February 3, 1959 became known forever more as "The Day The Music Died" (ED NOTE: this contradicts the common legend that Waylon Jennings was the one who gave up his seat for the flight).

A Divine Plan

"From that moment on, I knew God had a plan for me," Dion writes at his official website. But it wasn't until hitting rock bottom in the late 1960's, just as "Abraham, Martin and John" was riding high on the pop charts, that Dion realized there was nowhere left to go but up. The reconnection beginning with his prayer at the Roman Catholic Church of his boyhood led him to a new phase of his career, during which he wrote and recorded four contemporary gospel albums for the DaySpring label, earning new fans and a Grammy nomination in 1983 for the album I Put Away My Idols. "There's a song... called 'Sweet Surrender,'" he said. "I still do that in person, and I explain why I wrote it. Basically I tell people that I grew up in a neighborhood where 'surrender' was a dirty word. A man did not surrender. But I found out that there's a 'sweet surrender'--it's not running away from anything, it's moving towards something."

That's a lesson in life from an icon who, along with Bob Dylan, is one of only two living musical celebrities (apart from the Fab Four) whose image graced the Beatles' Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band at the time of its release. "I met John Lennon, and he loved 'Ruby Baby,'" Dion said. "I guess he took (copied) the head off the 'Ruby Baby' cover. When he talked to me about that song, he loved (it). They used to do it in Germany." There you have it--one of rock's more enduring mysteries explained as a gesture of appreciation from one rock and roll pioneer to another.

I believe Mr. Lennon would have loved Bronx in Blue--not just for the depth and honesty of the vocal performances, the soulful lyrics, or the brilliant guitar work--though there are plenty of those things on the album. The songs represent a rock survivor in his finest, most realized moment so far, proclaiming through songs about love and loss that heartache is a path to redemption, and that music makes the process more bearable. Dion's second set of blues standards (due in part to the success of Bronx in Blue) should be released early in 2007, and he is planning a series of shows showcasing material from both albums.

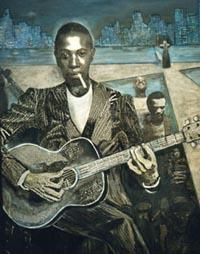

Portrait of Robert Johnson by Dion