Classical's New(er) Common Practice as Principle and Poetics

by Daniel Barbiero

(April 2019)

In the article "A New(er) Common Practice?", I suggested that for a significant current in contemporary composed and improvised music, new instrumental performance practices, and the compositional possibilities they open up, all stand as something like a contemporary analogue of the old common practice of tonal harmony--a shared, more-or-less standard set of practices ready-to-hand for composing and performing new music. Here, I would like to extend this idea and suggest that these practices are more than a collection of techniques, as important as that may be in itself, but constitute something like a creative principle for contemporary music. Seeing this requires us to step back a moment and take a broader perspective--one that comes from abstract visual art.

In an essay on abstract painter Robert Motherwell, philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto addressed Motherwell's setting for himself the task of identifying and articulating the "creative principle" informing his work. As Danto described it, such a principle "could not be discovered by simply continuing to paint, but rather by putting painting at a certain distance and determining how it could be done."

For Motherwell, an artist deeply affected by his contact with some of the leading Surrealists during their period of American exile in the early 1940's, that principle was to be found in psychic automatism--writing or drawing in the absence of conscious control or deliberate self-censorship. In an October 18, 1978 letter to Edward Henning, Motherwell explained that psychic automatism could serve as such a principle because, "A:... it is not a style; B: it is entirely personal; C:... by definition... [it] originates in one's own being; D: it can be modified stylistically and in subject matter at any point during the painting process" (emphasis in the original).

This is all very good and well for painting, but what does it have to do with music? Just this: the new(er) common practice and the assumptions about the nature of music that it embodies, serves as the original creative principle--in Motherwell's sense--underlying a good deal of contemporary art music. To see this, I'll start by unpacking what I think are some fruitful ideas implicit in Motherwell's points A through D. But first a caveat of sorts.

In his letter, Motherwell seems to have meant "psychic automatism" to refer to a technique that he and other younger American painters were developing during the early 1940's. The technique involved beginning a painting with a few marks set out by the hand, moving freely and without conscious guidance or goal. These marks subsequently would be consciously shaped into a finished work. On this narrow view, psychic automatism was simply an opening gambit, a preliminary technique. But the criteria Motherwell sets out, along with his designating it as a "principle," argue instead for a generality and applicability that go beyond a historically contingent process developed for a specific medium.

Motherwell's first two criteria seem to be closely related. Extrapolating slightly, we could say that, not being reducible to a particular style, a creative principle would instead be prior to a style--it would provide the conditions that make a style possible in the first place. A creative principle would be neutral in terms of form and content, in other words, and thus would be capable of facilitating whatever personally unique expressive substance it was called upon to realize. In short, a creative principle, while not itself being or inhering in a given personal style, is rather the facilitator of a personal style or a ground on which such a style can be created.

It seems to me that what Motherwell's first and second criteria describe are roughly analogous to method and methodology, respectively. A method--by which I mean the techniques and processes that go into the creation of a work--is prior to a style; it supplies the raw material of style, in a sense. A methodology--the system of organization by which those techniques and processes are deployed and used to realize a work--is what gives method a practical coherence. To use a linguistic metaphor: if method is--again, roughly--something like a vocabulary, methodology is something like the combinatorial gestures or syntax through which materials can be ordered and larger forms constructed. And as with the production of novel utterances in language, the production of new works of art drawing on an underlying method and methodology will be personal.

Points A and B quite naturally bring us to Motherwell's point D, which I believe is implicit in A and B. A creative principle unrestricted to any one style but specific to a given artist would, to the extent that it provides the basic material, processes or structures from which novel and unique works can be produced, presumably have the flexibility as a process or structure to accommodate the vicissitudes of style and content, whatever they may be. That is simply how a creative principle can be expected to work.

With points A, B and D, we have something like the what and the how of a creative principle; all that we need now is the why.

We can find the why in the most intriguing of the criteria Motherwell sets out in his point C. This is, in his words, that the creative principle "originate in one's being." There is much to pull out and translate from this vague, but somehow "right," intuition. To begin with, what can "one's being" mean here? In its most basic and--to use a much-abused terms that nonetheless seems entirely appropriate here--existential form, "one's being" just is one's sense of oneself as one finds oneself situated within a given activity, at a given time. This sense can consist in an unselfconscious, purely intuitive presence to self (as for example when we simply feel the movements of our body) or the reflected-on, explicit consideration of what we are thinking or doing that makes us an object of observation to ourselves. One's sense of oneself is a complex, dynamic knot of what one wishes to do, what one feels oneself able to do, how one integrates oneself into a given situation, and so on. In short, one's sense of self implies a grasp, whether implicit or explicit, of one's desires, skills, beliefs, and so forth, at any given time.

In the more specific context of an artistic process, whether of painting or of improvising musically, this--and here the term is unavoidable--existential grasp of oneself translates into a concrete, situated self-presence as one engages in the process of creating the work. It is the sense of one's being able to see or feel the performance or compositional situation as harboring possibilities for oneself, and thus of the work or performance as being capable of being realized on the basis of one's capacity to grasp the possibilities available to one and to render them into the reality of a cohesive work that effectively embodies one's formal or expressive ends. It is a method that is more than a method and a methodology that is more than a methodology; it is a way of being in relation to one's medium and material.

Taken together, I think Motherwell's intuitions generalize not only beyond his own medium of abstract painting, but beyond the particular principle--psychic automatism--he endorses. From Motherwell's list of the characteristics of psychic automatism we can generalize to say that any fundamental creative principle, regardless of medium or discipline, will 1) transcend particular styles, 2) be personal or somehow specific to the artist, 3) somehow express or represent one's sense of oneself in the act or product of one's creation, 4) allow for the ongoing modification of the work whose creation it informs, as that work is being created, in order that the work can take on a specific form or carry a specific content.

The applicability of Motherwell's criteria to the new(er) common practice is, I think, fairly straightforward. When considered in terms of personal style--Motherwell's points A and B--contemporary performance practices can be seen to supply a set of practical procedures and processes. For example, there could be a vocabulary of sound-producing gestures, methods of handling the instrument as well as ways and means of preparing or otherwise augmenting or modifying it, a set of operations for combining elements into larger structural units, and so forth. These are all prior to, and constitutive of--one might say prerequisites for--a style of one's own. That the availability of expanded performance techniques doesn't impose a rigid formal or expressive scheme on instrumentalists or composers (it is after all something made available, not mandatory) is consistent with the flexibility Motherwell describes in his point D.

And point C? To choose these practices is, in essence, to take up a fundamental orientation or way of situating oneself in relation to one's materials and creative environment. It is a stance I described above as "existential"; it consists in grasping those materials and that environment as concrete, creative possibilities which can be projected forward into novel works to be realized as one's own. It is, in other words, to engage means and situation from within one's own being, as Motherwell's third point would have it. As a practical matter, this existential dimension, which naturally will vary from artist to artist, will consist in judgments and intuitions relevant to the work at hand, whether that takes the form of composition, the interpretation of an indeterminate score, or the real-time unfolding of an improvisation.

In sum, the new(er) common practice comprises ready-to-hand methods of craft that can be combined in novel ways to create works in a personal style reflecting the critical judgments and intuitive formal and expressive senses of those who use them. This precis captures, in condensed form, Motherwell's four criteria for a fundamental creative principle. I also believe it opens the way for seeing the new(er) common practice as a poetics of music.

In "Two Hypotheses about the Death of Art," Umberto Eco asserted that in much contemporary art, its making was its meaning. Just so, many of the works informed by the new(er) common practice are works that take the conditions of their own making as their subject matter. They are fundamentally about the musical possibilities their technical resources afford. The method becomes the work's content, which is realized through a reflection on the means, a bringing it to the foreground of the piece or performance, rather than keeping it as a more-or-less neutral or transparent vehicle through which the composer's or improviser's (other) intentions are communicated. To a significant extent, the foregrounding of the method just is the intention. The meaning of the resulting work is, in turn--recursively--a reflection on or crystallization of the method and material through which it is realized.

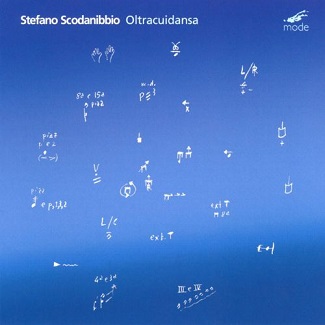

As an example, consider Stefano Scodanibbio's superb solo recording "Oltracuidansa." "Oltracuidansa" sets out the materials and methods of advanced double bass technique. Given its focus on technical procedures, one can describe Oltracuidansa as being in some ways like an extended, creative etude. And the comparison would be apt: an etude is itself a kind of intuitive methodology in that it highlights and allows the study of selected methods in the form of the technical problems it addresses. In this work, the gesture moves to the foreground and becomes its own reason for being. And yet, it remains a musical work, one that has something to say beyond its demonstration of Scodanibbio's consummate agility and fluency in the ways of making an instrument speak. He makes it speak with a voice that compels the listener's attention and frees his or her imagination on hearing it speak. This is an important point, more about which later.

"Oltracuidansa" is by no means a unique or unusual work in this regard. Any number of current artists working in the field of new music and improvisation--in addition to the artists named in my earlier article, I would add the names of instrumentalists such as bass clarinetists Aviva Endean, Amy Advocat and Charlotte Layec; double bassists Dario Calderone, Adriano Orru and Daniele Roccato; guitarists Daniel Lippel and Abdul MoimÍme; pianists Karen Leblanc, Silvia Corda and Nicola Guazzaloca; bassoonist Leslie Ross; and trombonist Patrick Crossland, to name just a few. They all give evidence of pursuing comparable concerns. An awareness of process or method is part of many contemporary works of ambition; it is a feature of these ambitious contemporary works that such an awareness is made a central--though by no means exclusive--element making up the meaning of the work.

That this is the case is so for reasons that Eco addressed in his essay. He observed that much of the discourse surrounding both the creation and reception of modern art--music included--focused on defining and contextualizing the methods or processes used to create a work rather than on its aesthetic or emotional value. As Eco suggested, to engage method as the meaning of the piece is, at least implicitly, to engage the history of the development of the craft from which that method is drawn. In a work that does this the meaning inheres in its making, in the concrete procedural or technical choices through which the composer, if the work is composed, or the performer, if the work is improvised or somehow indeterminate, creates or realizes the work.

Thus, contingency is destiny, since it is through its engagement with the history of its medium, that a work of this sort raises to explicit reflection the artist's--here, the composer's or performer's--engagement with and understanding of whatever fundamental creative principle underwrites the intention animating that work. And it is this reflection that brings the creative principle to the level of a poetics, if by poetics we mean something like a deliberate contextualization or definition of procedure, a self-conscious way of situating it within the history of the medium and within one's own personal artistic history--in short, a bringing of one's own practice to reflective awareness. What makes a creative principle a poetics is its (metaphorically) reaching self-consciousness. That it can do this through the work that embodies it as well as through thoughtful deliberation, works like "Oltracuidansa" demonstrate.

What I've called 'the new(er) common practice' underwrites or otherwise makes possible a poetics of music not only by virtue of the sheer technical innovation it affords, but also by virtue of the broadening of ideas about what can be done with sound, a broadening brought in train in no small part by those technical innovations. The new(er) common practice is thus just as much conceptual as it is technical. Whether technical or conceptual, innovation naturally calls attention to itself by virtue of its unfamiliarity; it focuses attention on the formal choices of the composer or improviser to such an extent that the resulting works may, as a result, be seen as an almost semi-epiphenomenal product. To listen to the work is de facto to reflect on the process through which it was made, and the artistic choices underlying those processes. Reflection on these processes and choices is what characterizes a work aware of its own poetics and sets it apart from works that simply realize their poetics in the service of some other content. In the latter case, process is subsumed in the product, whereas in the former case, process often is the product.

An artwork taking its fundamental creative principle as its focus is a work that is about the conditions of its own possibility, whether technical or conceptual. It is a work that is a reflection on its own ground of being, as it were. And this brings us back to Motherwell's point C, which I described above in explicitly existential terms. The work whose meaning derives from its creative principle is the work that portrays itself as a project of the artist composing or performing it--a project in the sense of an engagement, a reimagining and ultimately, a reworking of the given. Certainly a work like "Oltracuidansa" does this: it very much tells of Scodanibbio's personal engagement with the advanced double bass techniques he inherited and did so much to extend. A similar observation can be made of new solo work for other instruments--Ross's "Drop by Drop," for example, or Endean's "cinder:ember:ashes."

A project focused on the possibilities opened up by the new(er) common practice is a project of imaginative engagement with the given that seeks to transcend the given at the same time that it is transcended by the given--a movement of double influence or mutual formation in which the process of transcending-transcended is the implicit or explicit process of the work. In other words, the work, as it focuses on the given of artistic material or process--in this case, the existing set of expanded performance techniques--contains an understanding of this given as both something that can be imaginatively transformed and something that will transform the imaginative goal by virtue of its providing a real-world limit to the form this goal can actually take. The given limits the possible to what is actually possible by virtue of supplying the necessarily finite means toward realizing the possible. One cannot express something when one lacks the means to do so; in this way, the transcending project is transcended by the ground of its own possibility. The limits to expression imposed by the finitude of technique may in fact be an implicit theme in any kind of work--something just built into it. It is the virtue and interest of the work foregrounding technique and its limits that it makes this theme explicit, and even invests it with a kind of restrained pathos.

In sum, as a project the creative principle affords a grasp of the technical and conceptual means at its disposal as ready-to-hand materials to be taken up and transformed, and thus to call into being previously unimagined or unrealized sound worlds latent in the instrument, by extending the manner in which the instrument can be played. The sound of such a work--or better, the range of sounds it opens up--is the concrete expression of the possibilities that constitute it. Meaning is possibility, and possibility is meaning; both are realized in sound.

In the end, though, it's about music. The works centered on contemporary performance practices are ultimately about an expansive concept of music--about the possibilities open to music as a broad field encompassing sounds of diverse natures and origins. They, and the creative principle they embody, represent an opening of the imaginative field, or an opening of imaginative territory further afield of where one first entered in: a spirit of exploration couched in a sound-centered approach to music that looks to extend the possibilities of the instrument as well as the options open to compositional strategies. This goes beyond a reductively aesthetic orientation, with its stylistic strictures and substantive demands, and is instead a way of bringing methods and purposes to a new imaginative synthesis that illuminates them from within. This is something more than the kind of work Eco described as being a treatise on art; it is about imaginative and expressive substance as well as technical material. In other words, it is about opening the mind as well as the hand. And at that point, it goes from being a poetics to being poetic--a poetry of sound crafted from an expansive idea of what music can be.