CHUCK EDDY

Interview/article By Edd Hurt

(December 2016)

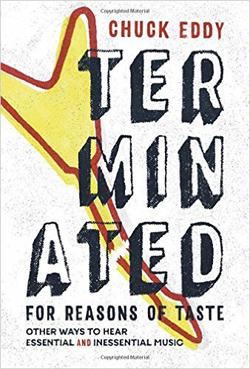

A piece rock critic Chuck Eddy wrote for his Michigan high-school newspaper in 1977 appears in his new book from Duke University Press, Terminated for Reasons of Taste: Other Ways to Hear Essential and Inessential Music. Published when Eddy was nearly 17 in West Bloomfield High's Spectrum, "Can't Fool Mother Nature" serves as an excellent introduction to his work. He notes the way students he dubs "granolas" seek to "convince people that they were completely unaffected by our technological society." Their idea of a good time is "climbing mountains and catching pneumonia." Eddy undercuts the '70's ideal of a return to a simpler, less materialistic existence by creating a list of granola essentials that just keeps growing: "a backpack, a pair of Earth Shoes, some hiking boots, a few pairs of flannel socks, some long underwear, a guitar, a cabin up north, a few hundred dollars' worth of cross-country ski apparatus, 12 pairs of Levi's, a couple duck-hunting rifles, some baking soda toothpaste, a three-year subscription to Field and Stream, a lifetime supply of granola, a Bill Walton for President poster, a mountain, honorary membership to the Friends of Apple Island [a 35-acre island in West Bloomfield's Orchard Lake], and all of John Denver's albums."

Born in Detroit in 1960, Eddy graduated from high school in 1978, attended the University of Detroit for a year and transferred to the University of Missouri-Columbia, where he took up a journalism degree. Not a teenage music fan--he appears to have absorbed Alice Cooper and Aerosmith and other essential American rock through osmosis--he began listening to new wave and punk in the late '70's and first voted in the Village Voice's Pazz & Jop poll of music writers in 1981. Voice music editor Robert Christgau published part of an eleven-page letter he sent in along with his 1984 ballot--Eddy bemoaned the sorry state of the era's rock criticism--and he started his music-writing career in earnest. Serving in the army's Signal Corps from 1982 through 1986, he honed the organizational and managerial skills he would later bring to bear as an editor. As his Spectrum piece had demonstrated, he possessed an eye for the telling detail.

Terminated for Reasons of Taste is Eddy's fourth book, and the second to collect previously published work. Some of the writing in Terminated first appeared on the I Love Music Internet forum. The book's title comes from the e-mail Eddy sent to his many friends, admirers and colleagues in April 2006 after being fired from the Village Voice, where he had edited the music section for seven years: "To make it brief, I have been ‘terminated for reasons of taste'; if you're wondering what that cryptic phrase means, my advice would be to look at just about any random music section in one of the many other New Times alternative weekly papers around the country, compare it to any random music section I've put together here at the Voice, subtract the difference, and draw your own conclusions." After leaving the Voice, Eddy worked as a senior editor at Billboard before returning to freelancing. He moved to Austin, Texas in 2009.

It's difficult but not impossible to describe Eddy's work in terms a professional musician, say, or a fan of popular music in its broadest sense, or a rock fan who also happens to be a jazz adept, would accept without remedial immersion in various post-Christgau, post-Richard Meltzer theories of rock, which means Eddy strives to explode notions about significance, durability and tradition musos and other concerned parties nourish in the fastness of their listening rooms. In his second book, 1997's The Accidental Evolution of Rock 'n' Roll: A Misguided Tour through Popular Music, a living museum of lists, list and more lists of songs and invented genres of music ("Fucking Sound Effect Records," "Garden of Eden Rock" and the indispensable "The Power Ballad Revolution"), he writes about "The Girl from Ipanema" as if it were a piece of "easy-listening mood-setting music" that had no "long-lasting effect" except on the "lounge revival" of the 1990's.

He has his method, which has turned me and many others onto ridiculous, misguided, well-made, stupid and altogether inspirational recordings we almost certainly might have otherwise dismissed or simply missed. But this same method may block the sunshine coming from some great music that doesn't necessarily announce itself with the air-raid sirens and klaxons and Jimmy Castor Bunch-fired missiles and profound banality Chuck loves and I certainly get off on but don't require for my ongoing mental health. I suspect Chuck hasn't listened extensively to the work of Antonio Carlos Jobim or João Gilberto--Gilberto's 1973 self-titled acoustic-guitar-and-drums voyage into memory, nostalgia and murmured repetition is a record I love more than I do The Clash and This Year's Model put together, and I bet Chuck would like it if he had the patience to sit with it for a while. I wonder if he's thought about how important, and here's the thing--useful--bossa nova has been to generations of jazz, pop and rock musicians. I wonder if he's ever talked to working musicians who could explain the significance of bossa's harmonic and rhythmic innovations and the way musical praxis of all kinds grounds the art and craft of men and women whose job it is to command the stage and deliver a piece of music in an elegant and correct manner. I'd love to see him spend some time in the woodshed and backstage--a rock Chuck Plimpton who learns what it's like to work with a rhythm section in real time-- with a group of players who are as hard-headed and joyous about making music as he is about describing it. The experience could make for a great piece of writing from a great critic.

In Terminated, he pans the work of Shelby Lynne ("her attempts at jazzy phrasing came off less ridiculous in her pre-critic-sanctioned western-swung Nashville days"), who was definitely hyped by the alt-Americana-retro claque when she was being touted as the next Dusty Springfield (you wonder if they understood Dusty as a pop star--everyone knows she was a great singer). Lynne may not have gone out and brought home the kind of material or the sympathetic production techniques she needed to break through as a pop artist, but she's a very good singer whose lesser work can teach any music critic about phrasing and what it takes to get up and deliver the goods, quite apart from any attempt to create a taxonomy of music based on its external qualities (and yes, the division of what's inside and what's outside an artwork is problematic in criticism, and I have no doubt Chuck is acutely aware of the difficulty in making the distinction). In other words, I think it's neither boring nor ridiculous when an artist brings technique to bear on problems whose solutions may not hold the key that unlocks the double-swinging door of ultimate significance and transcendent meaninglessness.

No one can do or be everything, of course, and Eddy's writing about music walks when it's not running along the rough path of American self-sufficiency. Being practical about the theoretical (yeah, you can reverse that formulation if you like), he knows how to balance reportage with humor, and he describes the way music sounds in ways Whitney Balliett never dreamed of ("crooked plinks and plonks and open spaces and drunken classical strumming and sour New Orleans funeral-wake tubas or foghorns or whatever," from his Terminated review of Outsiderz 4 Life's "College Degree," is a representative example of his method). Chuck has a nose for the the way professionalism, technique and so-called innovation often fall short of the mark--writing in 2009 about Bruce Springsteen's Working on a Dream, he declared, "What I really really really hate is Brendan O'Brien's totally vacant and antiseptic New Age bachelor-pad Muzak schmaltz production touches, which I gather are supposed to give the music space and drama, but to me just drain it of any life."

Elsewhere in Terminated, you'll find a piece on Billy Joel that is sympathetic to Joel but which doesn't make, as far as I can discern, such a convincing case for his music. Examining his own assumptions instead, Eddy describes the democratic impulse as it operates in pop. Like me, who has never been able to stomach Billy Joel, Chuck once found him a purveyor of "ponderously anal-retentive maudlin sentiment." But he eventually gave in to Joel's smarm and learned to love his great big bruised ego, his undeniable melodic gift, and the "archipelagoes" (Eddy's joke) of a piano man who, Eddy thinks, got better as he aged while critical favorite Randy Newman got worse. What is Eddy getting at here, you may ask, snug at home and secure in your taste? I think he recognizes that, in pop, the density of hits (collected on Joel's 1985 Greatest Hits), and the collective experience of hearing such high-powered examples of musical-verbal invention, can allow us--force us, even--to perceive Joel's lapses in taste (to my ears, also undeniable) as meaningful, uplifting, powerful. I also admire Eddy's assortment of short takes on neglected ‘70's and ‘80's bands (he found their records in dollar bins), one of which details a forgotten masterpiece of power pop-prog-disco-Jaco Pastorius-Steve Miller Band synthesis by Dutch band Diesel. He ends the book with a piece on country singer Mindy McCready, who committed suicide in February 2013.

I caught up with Chuck at home in Austin in late October. The following is an edited version of our hour-long conversation.

Chuck Eddy: You mean what I'm writing about, or what I say?

PSF: Everything. I appreciate the reportage in the book. Your piece on Mindy McCready is really moving.

CE: It's weird, because that's an obituary, and I kind of hate writing obituaries. I don't know, I have some kind of weird psychological, mental block, I think, maybe ‘cause my parents died young or something. Like I really dread it, and it's also hard for me to use my voice. There's something about the form of them that doesn't... I mean, you know, people write them, people are great at them, but you're basically saying this person was important because of these things, and that's not how I write or really how I think in general, you know what I mean? It's like I always want to criticize them, you know, but it's also like a psychological thing with death. I find it really depressing. Like, honestly, when Bowie and Prince died early this year, I kinda just stopped reading stuff. But yeah, the McCready one, I guess, because of the circumstances of how she died, and my own history, for some reason that just worked. That's why I ended the book with it. Except for the actual conclusion.

PSF: I've written a lot of obituaries. Sometimes the deadline pressure is intense, and other times you have a little more breathing room.

CE: That's the other thing: I find them really stressful, flippin' them so quick. I mean, I don't know whether you picked up this in my writing, and we're like kind of on opposite poles as far as this goes: I don't write in general that much about performers' lives. Maybe incidentally I do, but I've never really gotten into, say, reading biographies of musicians. I never do it. Anyway, when I was editing both at the Voice and at Billboard, finding people who are good obit writers, that's a really valuable skill. When I was at the Voice, Joey Ramone died and Joe Strummer died. Jam Master Jay died. As an editor, you have to find somebody, you know, like really quick. At the Voice, if it was an important New York person--Tito Puente died, I think, when I was there [Puente died on May 31, 2000], and they always died on a Sunday, and the paper would close on Monday--you gotta find somebody, like, now. I think Joe Strummer died early Monday morning. I mean, it has to be somebody really good, and as an editor, I found it really stressful. It was one of the least favorite parts of my job. But when I did the McCready thing, for Spin, they let me take a couple days, and I don't have instant recall. I think I even say this in the conclusion [to Terminated]--people might think I have an amazing memory. Maybe I just take really good notes. But I wanted to go back and listen to all her stuff. It had been several years since I had really thought of her. Even if you're talking about the music and not the biography, I need to go back and hear it. And how you do that in two or three hours, it seems like superhuman to me. But anyway, the McCready thing, I like how it turned out.

PSF: I like your short piece on Diesel's "Sausalito Summernight" and their Watts in the Tank album.

CE: It doesn't fit in any genre. I don't know, Golden Earring's music, I've graded a few of their albums or whatever, and there's something interesting going on with prog in central Europe, beyond like Krautrock or whatever. Golden Earring had two really big hits eight years apart or something like that ["Radar Love" made No. 13 US in 1973, and "Twilight Zone" hit No. 10 in 1982]. That's the closest thing, especially because they're also Dutch, I guess. But yeah, it doesn't seem tied to any one thing, and nobody mentioned it at the time. I doubt that album got reviewed in Rolling Stone or anywhere else; I'd have to go back and look. But anyway, the dollar-bin thing, you know those were just written for ILX [I Love Music]. They're edited down and kinda cleaned up a little bit--those especially, ‘cause I was writing off the top of my head, taking out typos and redundancies, holding patterns and whatever. I consider that, and sort of the fake new wave thing, as the Stairway to Hell [subtitled The 500 Best Heavy Metal Albums in the Universe, his first book, published in 1991] section of this book. I think [those] are where the tone is closest to the tone in Stairway to Hell. And it's a tone, I can't just do it at will. In Stairway to Hell, there was kind of an end goal in sight, and with these, I was just goofin' around. I got this album in the dollar bin and I would do a post on ILX. Those are really culled down--these were what I thought were the best ones. There were way more albums I wrote about that I didn't think I said anything particularly interesting at all about, so I got to pick and choose, which I did through the whole book and my previous book [2011‘s Rock and Roll Always Forgets: A Quarter Century of Music Criticism], too. It's like I say in the introduction, a "worst of Chuck Eddy" would be much thicker, I think. I've done it for money for 35 years, and a lot of what I've done isn't that--it's making a living.

PSF: I've done a lot of short reviews myself, and some of them are pretty good and others are more perfunctory. I cover a lot of B-minus Americana acts in that format.

CE: This is something you don't know about me and Americana. And by the way, I do more playlisting now than writing, for Rhapsody/Napster. That's not my music, as you know. I do an Americana playlist every week. It's a 50-song playlist. I change maybe an hour of it every week. It's not even music I necessarily listen to. I see what new (stuff) is out that week. I have a pretty expansive definition: a lot of Texas or red-clay country stuff. You know, I can work in blues-rock or Southern soul sometimes. I think I put in a couple Norteno cuts or whatever. I'm not necessarily keepin' up with it. A lot of it, I'm just looking at what Americana artists you or other people might post on, say, ILX or Facebook, or see written up in The Austin Chronicle. Austin's a pretty good place to keep tabs on what's comin' out. I've probably developed more of a respect for it. Again, very little of it is stuff I would listen to out of choice.

PSF: I'm an Americana skeptic, but I like someone like James McMurtry pretty well.

CE: Yeah, I respect him. I have one or two CD's on my shelf, you know, with "We Can't Make a Hero" or whatever that song is (ED NOTE: "We Can't Make It Here Anymore"). It's a good song, but it's not something that I would really put on. But also, the thing is, I like some of the more cowpunkish stuff and I always have since the ‘80's, and the weirder stuff, and there's a label here called Saustex out of San Antonio who release stuff that's somewhere between cowpunk and Gogol Bordello or somethin' like that, and Alternative Tentacles, who have this band called the Woodbox Gang. I like some of that kind of stuff. I can slip one or two of those onto a playlist, and ‘80's cowpunk stuff, or even a Johnny Rivers song or something. They want it to be old, new, borrowed and blue, you know. Say, the Paul Cauthen album [2016‘s My Gospel]--I think you were a fan of that, right?

PSF: I like it OK, couple of good songs.

CE: I guess the melodies are there a little bit. A kind of lame Chris Stapleton, maybe. Like this kind of new country-soul. I won't say constipated, but it seems super-stodgy to me. And why am I blanking out on the other guy, who covered Nirvana this year?

PSF: Sturgill Simpson.

CE: Yeah, Sturgill. You saw what I wrote about Jamey Johnson.

PSF: I agree with you about Jamey Johnson. He lays the template for Chris Stapleton and Sturgill Simpson.

CE: That's what I mean. I like how he reinvented himself on those two albums [That Lonesome Song and The Guitar Song]. Who knows what happened to him in the last few years; he just kinda disappeared. Sometimes I like how Eric Church reinvented himself. The album last year [Mr. Misunderstood] I really liked. The one before [2014‘s The Outsiders] when he did the metal stuff, I thought a lot of that was just kind of, you know, stuck in the mud when he's trying to do Pantera or Metallica. I appreciate those guys. Maybe some people consider Jamey Johnson Americana. I don't really understand where people draw the line. There's that weird period in the mid-late ‘80's when Lyle Lovett and k.d. lang had actual country hits, and Mary Chapin Carpenter for a while there. That's kind of an era I find a little bit--maybe it was trying to get a little more upscale or something. Just what exactly happened to country radio I'm not sure, and I guess with Garth [Brooks] and Shania [Twain], that kind of went by the wayside.

PSF: Did you have the theme of "essential and inessential" music when you were putting the book together?

CE: No, that subtitle just kind of came to me after it was all put together. I mean, the thing is, any of my books are probably about essential and inessential music, you know what I mean? It's not like this one is more. What happened was, a couple years after I put out the previous collection, Rock and Roll Always Forgets, I started noticing pieces: "Oh, wow, I should have included that," you know what I mean, just going back through stuff. And I was still writing a lot then, and a lot of the pieces in this one were written since 2010 or 2011: the "Sonic Taxonomy" things about "Old Old Old School Rap" or unsung R&B and all those country-song blurbs from Complex that are all through the book, and the ones where I'm comparing a current artist to an older artist--No Age and the Urinals and M.I.A. and Frank Chickens and Mayer Hawthorne and Robert Palmer. So anyway, I'm like, "Oh, I'm writing some good stuff now," and I'm noticing some older stuff that's as good as the stuff in Rock and Roll Always Forgets. So I just started keeping a list, and eventually it got to a point where I'm like, you know, maybe I should ask Duke if they'd actually want me to do another book. When they did, I then painstakingly went through all my files, just from the beginning, the earliest Voice and Creem stuff, even the piece I wrote for my high-school paper, that little thing about "granolas" or whatever I call it. I would be, like, "OK, this is in," and some things I thought were gonna be in didn't make the cut. The list was probably twice what ended up in here. I thought it was pretty together, and maybe I would write something else that would fit in or whatever. Rock and Roll Always Forgets, that's divided by genres--there's a metal section and an alt-rock section and a country section and a hip-hop section and so on. In this one, at some point, it occurred to me that I obviously don't want to do it the same way, but it had to have some kind of structure. So it occurred to me to do it in this kind of decade format. But then I had all these things where I just wrote about, you know, music from 1930. I have a section on the ‘70's, so I had this idea to have that "B.C." chapter, which is sorta like Before Chuck, or Before I Was a Critic, whatever you want to call it.

But as far as that subtitle, I can't even remember when that occurred to me. The thing is, for a while, the column I was doing for Spin was called "Essentials." They would have me do a genre and write about eight albums, and when it went online, it became "Sonic Taxonomy." I guess it just occurred to me that a lot of music I like is not essential, you know, and a lot of what I like writing about and a lot of what I like reading about, it's not, you know, I saw the Anvil movie [Anvil! The Story of Anvil, subject of a piece in Terminated], which is [about] this band who were sort of a nothing. By inessential, I don't just mean avant-garde or something. I mean bands who wanted to be big and weren't. They're just kind of ignored or they fell through the cracks. There's a lot of that kind of stuff in Stairway to Hell and probably in all my books. I think I probably submitted a couple of possible titles and subtitles to Duke, and we kind of went back and forth and decided this title and this subtitle. The other thing I like about Other Ways to Hear, that first part of the phrase makes it sound kind of academic. I don't know--I'm not an anti-intellectual, either. Early on, I used to be accused of it, and there might have been some of that. I think I refer to that Midwestern, uh...

PSF: You do. "Anti-Eastern Seaboard elitism."

CE: Right, right, and early on, I probably did have a little bit of that. Whether it was kind of a Midwest chauvinism or whether it was an actual looking-down-my-nose at people I thought were looking down my nose, or whether it was just a shtick--whatever. There was definitely some of that in my earliest ‘80's writing about metal and John Cougar Mellencamp and stuff like that.

PSF: You're sometimes accused of being a contrarian, but I don't see you that way. It seems to me that you're trying to alert listeners to how much seemingly extraneous inspiration goes into making pop and rock music.

CE: Right. It's just never cut and dried. With Stairway to Hell, it was like, OK, if Jimi Hendrix is one of the prototypical metal guys--which metal people might argue now he wasn't, but back then it was no stretch--if he was, then certainly some ‘70's Funkadelic belongs in there. If that does, obviously some Prince does, and if that does, then one side of Teena Marie's most rock-oriented album does. You know, if this fits, then maybe this should fit. There's a lot of jazz albums in Stairway to Hell, too. Three Miles Davis albums, one Last Exit, Sonny Sharrock's solo albums. I can't remember what else. Then there's an album by the Headhunters and a Jimmy Castor Bunch album. If Hendrix fits, the Chambers Brothers album with "Time Has Come Today" seems like it should fit. I wanted to expand it racially and gender-wise and stuff like that. A lot of that was just me playing with the form, but it wasn't like I was trying to pull the wool over peoples' eyes. I think the one thing that was sort of contrarian in my early writing is, there were a lot of times where I might review some artist positively, but I would include some kind of gratuitous line about some critical favorite. Now when I go back and read it, I'm like, ‘boy, that line really sticks out like a sore thumb.' There was a sense that at certain times, I was trying to get a rise out of people. But those pieces, for the most part, aren't included in the book. I didn't think they were that good. There was stuff that to me read much better than I remembered, like that Billy Joel piece from the Voice. I had barely remembered even writing it. I was like, you know, this one actually holds up. And the goofy John Hiatt thing. And the thing is, I'm so detached from it time-wise, it's almost like I'm reading somebody else.

PSF: Are there things you wish you'd written about, or things you regret missing along the way?

CE: If I had to go back from the beginning, I'd probably try to write about a lot more than just music. I know that's not really the question you're asking. I say at the end, people can say, "Gosh, I really have expansive taste," and can talk about the scope of what I've written about. Eventually, this is my career, and anything else, I'd be starting over, Especially as somebody who started out as a journalist writing about zoning commissions and sewage boards and sports and stuff like that. I wish I would've tried to do more book reviews or TV reviews, at least. But the way things worked out, if there was something I wish I would've written about, of course there's things, music from the ‘80s. I obviously wrote about Teena Marie back in the ‘80s, but there's things I like in retrospect that I just wasn't paying attention to at the time, is what I'm saying. Now you can go back and write about that stuff. Which is what a lot of this is--it's music written about in retrospect. So I wouldn't say I have major regrets.