Hot Dogs, Tires, and Beers

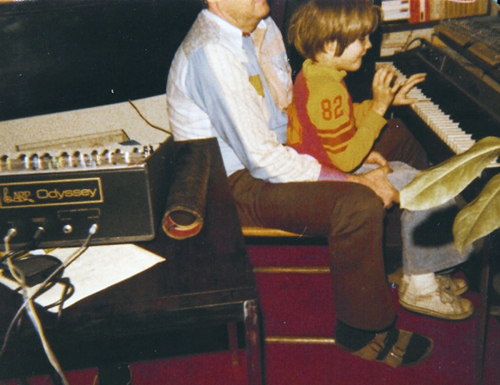

Bob taking a break with me to noodle on the Fender Rhodes. Pecking out "Snowball" by Devo became a teachable moment on modalities. The ARP Odyssey at left

The 1,000 TV Commercials of Bob Thompson

by Spenser Thompson

(June 2018)

"Ball park Franks, they plump when you cook 'em" and "The Rrrrrollling Writerrrr Pentel Pen," are two snippets of voice-overs from the 1,000 commercials that my father, Bob Thompson, scored. These two ads came out in the late 1970's, when Bob's music career was entering its fourth decade. About 20 years prior, he made four records (anthologized here): three for RCA (MMM Nice! , Just for Kicks and On the Rocks) and one for Dot records (The Sound of Speed) that became exemplars of what WFMU's Irwin Chusid dubbed 'Space Age Pop.' A resurgence of the genre and reissues by RCA in the US and Japan would not happen until the 1990's.

Before Pro Tools, scoring commercials came with a technical burden. Bob and my mother, built a multi-page document with tables that converted BPM to frames-per-second, bound with masking tape. This bible was completed in pencil his 9"x12" monogrammed music paper. Between playbacks of the voice-overs, I would hear Bob pressing the button on the stopwatch while whistling to himself. Many times, these sounds would waft into my room for 12 hours straight. Now and then, he would play what he had written the Steinway B, then stop in the middle and start erasing. He was embarrassed about dropping so many eraser shavings under the strings.

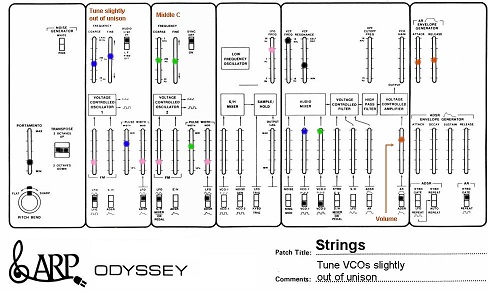

Van Dyke Parks, a friend who hired Bob for arranging duties on projects such Roger Nichols' Small Circle of Friends and his own "Canon in D", described Bob as "one of the big band guys who was able to make the transition and keep working in the '60's and after." Bob made a study of rock, soul, how the Fender Rhodes was played in pop music, and the advent of the synthesizer. He incorporated those styles judiciously into commercials--even though his passion was playing Jerome Kern, Thelonious Monk, or a minor blues on the piano. He bought the first ARP Odyssey, a monophonic synthesizer with big plastic overlays that fit over the switches and sliders. One template was generously called "strings." As I recall, Bob switched and slid his way to a bouncy square-wave to dramatize plumping Ballparks. You can hear the ARP and the Rhodes in Levi's' "Trademark." Truly an ad only an agency could love, a man takes the jeans logo for a walk on a leash--with a rhyming-couplets voice over that begins with great affection: "Come on, ol' boy..."

ARP Odyssey overlay of strings. Korg revamped and re-launched the brand 40 years after its 1972 introduction. [http://www.arpodyssey.com/Patches/odystrings.jpg]

When the scores were done, the music copyist stopped by and then drove down the hill to write out the separate parts for the musicians. I once asked Bob about the RCA records: "How many takes did it take to get the track down?" "Takes?! These were the best musicians in the world!" This was almost the best part of the job for him, having local jazz guys and members of the Wrecking Crew at his disposal– a group of musicians who also added dimensions to songs by the Monkees and others and made them hits (in very few takes!).

Bob often went to his Local 47 musician's union book and called up the Crew's drummer, Hal Blaine. Hal once left the first iteration of electronic drums (think of the sound in Anita Ward's "Ring My Bell") at our house in 1976. Looking skyward, Hal dramatically uttered an idea for a Star Wars-inspired electro-percussion album: Drum Warrrsss. Beyond the Wrecking Crew, Bob often hired LA jazzers Red Calendar (bass), Frankie Capp (drums), and the impossibly cool percussionist Larry Bunker--who played drums for Bill Evans at the Baked Potato on Lankersheim and hammered the xylophones on Bob's RCA records. You most likely are hearing Bunker on the percussion-driven "When Snow Says No, Go Goodyear."

A note about the Musician's Union Book: Once, somebody the called wrong Bob Thompson to play piano at a party. "The Gauntlet has been thrown," Bob told his wife, my mother, and went anyway. Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland were there among other swells I cannot recall. They played and sang all night.

Driving to the Studio & The Dates

Exterior of United Recording Studios on Sunset Blvd.

The music copyist would show up late at night before the date, many times. The next morning, the scores went into Bob's Vuitton briefcase with a matching flask full of vodka. The briefcase, in turn, went into the white Mercedes 250SL that had a license plate that read 'YADA.' Long before Seinfeld changed the meaning, the word was a quote from Lenny Bruce's "Hollywood prison picture" satire. A desperate prisoner leading a revolt growls at his negotiator, Father Flotsky: Yada! Yada-yada!

It was time to drive to the studio. Bob lived on Woodrow Wilson drive in the Hollywood Hills and would first make a right pass the "lawn" of white rocks in front of Marvin Hatley's house, the man who wrote the Laurel and Hardy theme ("The Dance of the Kookoos"). Right across from our house, behind generous trees and ivy, lived Ralph Burns: a deft arranger who put together a universe of textures for a Tony Bennet album called Jazz. (That's the gig I wish my father had, God dammit!). Next, Bob made a left on Mulholland and then a right on Nichols Canyon – where Stravinsky and Ringo lived, as Bob liked to mention – that took him United Studios on Sunset.

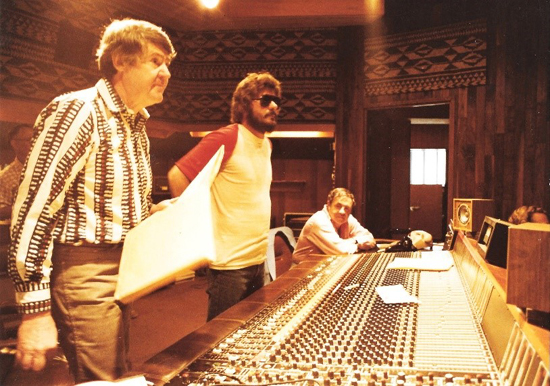

Bob (left) with good friend and ad agency creative Norm Toback (196?). Toback's son, a bassist and singer-songwriter, recorded a jazz-alt-art-folk solo album for Blue Note in the 1990's

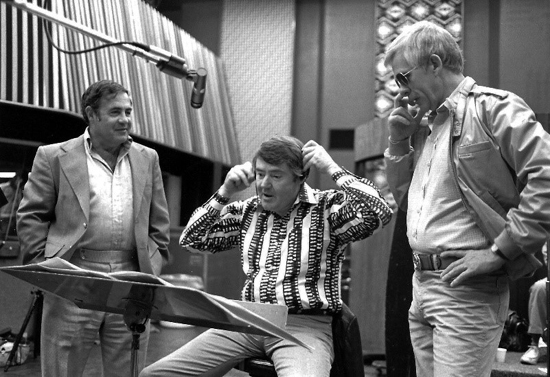

Coming in from the bright sunlight into the dark, sound-proofed, Bob and his crew talked in a dialect Bob called "musician's talk--not really black or white." Time for a musician joke: A big band is going like mad. When the set ends, they come back stage. Someone stops one of the guys and says, 'That was really swingin'!' The player replies: 'You should have seen the rehearsal!'

The studio booth (pictured) was of course manned by a sound engineer (middle), looking appropriately shaggy and a bit coked-out in sunglasses, and an ad guy (far right). Often creative directors were in the studio and would say things like "make it sound like trees," but there were savvy ones like Norm Toback (no relation to slimy director James Toback), who became a good friend.

Bob (far left) at United Studios with engineer with sunglasses in the middle (it wasn't exactly bright inside) and ad man is at far right

Bob counts off and starts conducting with his pencil. Boy, was the music loud! It may have been low-art, but it was music at least, and high-fun. One day, my parents pulled me out of 6th grade and nudged me out on the studio floor. If there was a moment of total mortification in my life, that was it. The sound went right through me and I had no idea what to do with my hands.

Just for kicks, a trip to Musso and Franks followed the date for a drink on the rocks. Maybe a discussion of Waiting for Godot or spirited quoting from Lord Buckley ("When The Nazz [Jesus] layed it down, it stayed there...") would be on the menu. It was mmm nice, indeed.

The Blues Have Been Good to Us

By his count, Bob did about 1000 commercials from about 1960-1983. Hot dogs, banks, and beers paid nicely and sent me to fancy orthodontists in the Valley. At the very start of his career, commercials for Fling Stockings and Bank Americard have the feel of his Space Age Pop. The Go, Go Goodyear! theme ran in various incarnations for years as did the Mr. Goodwrench ( "Get That Great GM feeling with genuine GM parts" ) campaign that was musically unremarkable but lucrative. McDonalds, Hamm's, Budweiser, Bank of America, Dow/Corning, Texaco, Mattel and other ultra-American companies hired Bob through the biggest agencies like Ogilvy. NARAS and Clios lined the walls. David Brinkley complimented the music on one of Bob's commercials on-air during the nightly news. Probably a first, and last.

How did Bob go from a one-time Barney Bigard (Duke Ellington) sideman, to being Rosemary Clooney's arranger and RCA recording artist – and by some accounts in the same "ballpark" as Spike Jones (according to Van Dyke Parks) -- to doing commercials, exclusively? Nobody bought Bob's RCA or Dot records – which were intended by the record company to compete with flat fare such as Les Baxter. Bob said: "My direct competition was 'How Much Is that Doggie in the Window.'" MMM Nice! (my favorite Living Stereo offering) and the others were a bit too crafty and musically adventurous for RCA and stayed "turntable hits." After the solo records, the tasteful pairing of Rosemary and Bob was an artistic success: especially on the arrangements for "Aren't You Glad You're You" and "Black Coffee" --tracks that sum up their charm and smoky-ness, respectively. Unfortunately, RCA assignments for Bob followed, such as creating a bed for E-string plucker Duane Eddie in Twangy Guitar, Silky Strings (Bob providing the latter). The RCA days over, Bob became, as he said, "known as the guy that does commercials."

Bob had a sly sense of humor about the commercial work (although crying inside a bit). I can almost hear him saying: "Well, there you have it gentlemen. It is art!"

But Is It Art?

Bob liked to use were lush strings, vocal choruses, and percussion-driven songs for commercials. There was real beauty to the string arrangements, many of which accompanied cars rolling down the California coast. The Rolling Writer commercial (1979) is supported with a lovely string quartet and is a truly clever piece of advertising. Some spots even lasted 60 seconds with more room to play with. Drums were Bob's first instrument, and you can hear the love for percussion in the multi-xylophone and drum attack on RCA songs like "Playboy" and an all-percussion commercial for Goodyear (1960) – with a voice-over that is probably the most sexist in history ("What does a lady do when she has a flat tire, when a man isn't around?"). For a Bank of America Home Loan spot, Bob assembled a "carpenter orchestra," with an actual nurse standing by who was the girlfriend of one of the players.

Conducting all-carpenter band with a rubber hammer for the bank loan commercial.

As with Bob's commercials, it is not art, but there is an art to it. Bob used to complement guys like Van Dyke Parks as "musician's musicians" and I count Bob as one also. A student of professor Douglas Denny at UC Berkley, Bob studied music theory and did his first arrangements at KGO radio for a live orchestra. He was truly music literate and used this skill to write in various styles. He wrote a Superfly-style Colt 45 Silver commercial, which my mother insisted was the "first use of music that funky for a commercial." One spot for Stouffer's frozen dinners showed off their takes on world cuisine ("Spanish paprika!") which required switching from style-to-style-- a synching nightmare to be sure. Lots of stopwatch clicks.

There are moments of real artistry in Bob's "commissioned" work, even in the whip-smart Industrial musical penned with friend Alan Alch, That Agency Thing, a show-tune and Kurt Weil-esqe audio play about life at an ad agency.

There were only a few TV gigs, including the second theme for 77 Sunset Strip and scoring many episodes of the Ronald Reagan- and Jack Webb-hosted GE Theater. He "over did it" when he some florid string cues for the Ben Casey medical drama. He was fired. The deepest lows for Bob were scoring an episode of BJ and The Bear (a Universal show about a big rig driver and his "best friend" who happened to be a chimp) and a gospel album. Bob's attitude on religion was borrowed from Lenny Bruce's cynical "Religions, Incorporated" piece. Again, Bob holding his nose allowed me to hold three advanced degrees.

"Show Business is Not for Wimps."

The commercial work was lucrative, and composers and arrangers were paid better than the players. Bob bought a cantilever house in the Hollywood Hills on Durand Drive and then a bigger house with a pool and a view of Universal Studios at the end of a half-acre path. He was fond of a New Yorker cartoon that showed a longhair musician reclining in front of a mansion-- a skinny half-nude woman next to him. The caption read: "The blues have been good to us, Binky." Indeed, they had been good to us. We'd watch TV and every so often Bob would say: "That's one of ours." Inside the mailbox, we'd find residual checks that he opened immediately. They added up.

Bob Conducting at United in 1980.

Unfortunately, the people that hired Bob retired, and orchestras were replaced by synths. The checks got smaller and less frequent. Growing up poor, having been sent out on a ladder to pick berries during the Depression was a low point, Bob spent like crazy once he had money. He pointed to the Mercedes Benz 250SE in a catalog and it was shipped in from Germany, which was why it was a rare two-door model in Los Angeles. Like Hal Blane recalled in the Wrecking Crew documentary, the work can be nonstop but doesn't last, and a divorce didn't help Hal or Bob financially.

An ominous sign of the end was when Pepsi thought it would be a good idea to have an ad called "Pepsi is For Swingers." They hired Bob to create a swinging Big Band arrangement for Mel Torme. Once the recording was done, Pepsi thought better of it, as the meaning of the word swinger had changed by the 1970's.

A failed attempt by Bob to relocate to New York to find work in 1982 was followed by a "forced retirement" and psychic paralysis of 15 years (and banishment to an apartment in Studio City where Kenny Rogers once lived). Lifting weights and taking an arranging class (!) at UCLA were cold comfort. We occasionally would run into Bob's friend, Broadway stage actor Gordon Connell, in the banal parking lot Studio City Safeway. As Gordon said during one of these chats: "Show business is not for wimps."

After a meandering car trip in the aughts, he wound up in Eureka (a small town on the northernmost California coast) and had a self-described Eureka moment. He would arrange a bunch of Gershwin tunes for string quartet (see https://www.bobthompsonmusic.com/bob-thompsons-story.html). This was an act of salvation and redemption, something hi-brow that his middle-brow Space Age Pop and low-brow commercial phases didn't quite touch. And it is pure Bob: sly, romantic, inventive, and reverent of the giants. Top musicians recorded it in LA for free. A medley at the end of this unreleased album is "Rhapsody in Blue," in which I distinctly hear Bob reflecting on the totality of his life and that of the Artist-- the deep valleys and the sounds of singing angels from the highest hills in Hollywood. Thank God he got the string quartet project done.

The last time Bob played music was in the common room of the Motion Picture & Television Fund senior unit on Mullholland. There was an upright piano I encouraged him to play, but his mind was betraying him and we both knew it was too late.

Bob passed away from complications from Alzheimer's disease about two years later. You can find the 2013 obituary on the LA Times website.

And boy, those franks sure do plump when you cook 'em.

Musician's Union on Vine St. was another frequent stop for Bob. [credit: la.curbed.com]