Waiting for the Right Time, A Tale of Two Sixties

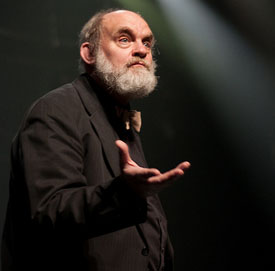

photo: Robert John Godfrey at Nearfest 2010

© 2010 Kevin Scherer

Barclay James Harvest, Robert John Godfrey, and an Absence of Justice

by Mark S. Tucker

(March 2011)

"My friends, it's not what you were famous for / But now the whole world's watching you / ...we don't know just what you do / We never tried to understand / ...who's the one to take the blame?" - Lines from the first stanza of Barclay James Harvest's "Kiev"

This is a follow-on to my years-earlier overview of the Barclay James Harvest catalogue, which can be read in the Perfect Sound Forever archives (and I strongly advise scanning that lest certain aspects of this interview not be as clear as they should). As observed there, composer-conductor-player Robert John Godfrey played a crucial part in the group's formative years. In fact, as I noted in the long essay and interview, the magnificent BJH /Godfrey song "Dark Now my Skies," which ran very intermittently on underground radio here in L.A., so blew me away at the tender and impressionable age of 16 that I one evening dragged out my 10-speed and biked the 35-mile round trip from Hawthorne through South Central Los Angeles to the Hollywood Tower Record Shop late at night. I hustled into the shop, spotted the way cool stained glass butterfly artwork on the cover, nabbed the LP, rushed to the counter, whipped the bucks out of my wallet so fast that they caught fire, sprinted back to bicycle, and peddled like a madman home. Breathlessly, I threw the vinyl on the plattern in my cheap stereo - a Sears Reck-A-Reckord Deluxe, if I recall correctly – planted my head between the speakers, and played the entire slab five times completely through. I'm not sure the drugs I years later ingested ever came quite so close to that bliss.

"Dark" still ranks as one of the great progrock songs, and BJH yet retains their place as a premiere outfit in my personal music halls and sonic affections... despite a spate of their rather nasty treatments of Godfrey. The group refused to recognize the gent's genius properly (and one need merely listen to his later group's, The Enid, debut release, In the Region of the Summer Stars, to grasp that I'm not abusing the aggrandizing sobriquet), and this eventually touched off a two-decade slog through the British court system - to a result as dismal as what the esteemed composer would have received on these shores. That sordid interlude always nettled me, so I asked Mr. Godfrey a set of legal questions (I'd been studying law at the time... until the police escorted me out of the school and I two years later shut it down; long story) which he very politely declined to answer, gentlemanly inviting me to pop ‘round should I ever find myself in Jolly Ol', where he'd enlighten me privately.

Well, I hate any mode of travel other than in a sturdy van headed for hiking on the Colorado Plateau, so I thanked him and essayed that this would probably never happen, much as I might wish otherwise. With a small pang of regret, I left off, for a moment reflecting how Godfrey was not the only lad to be thus ill-served. Pat Moraz had undergone similar rough seas with the Moody Blues, and there are more than a couple of other instances, but, dear Gawd in Heaven, how I'd dearly have loved to help set the damnable record straight. Well, nothing for it, eh? And so, as Pepys said, off to bed.

Thus, imagine my surprise when, a lustrum later, RJG sent me the entire set of questions back, answered! Sweeeeeet!, thinks I, and so delved into his responses. Very very good ones indeed. They shed light on more than one aspect of those halcyon, albeit bittersweet, days, and it was probably no coincidence that his reply coincided with Prog magazine's (one of the spin-offs of the great MOJO empire) coverage of his old associates and him, but I'll pride myself momentarily that what you're about to read here, you will not read there.

And to all aforegoing, I've only one comment in the form of an instructional: listen to the first seven or so Barclay James Harvest LPs, then toss on the early Enid materials (while you're at it, sneak a listen to Craft, an Enid offshoot), and try to imagine what might have resulted had Godfrey been properly admitted to BJH as the fifth member.

My God.

PSF: To start off, the Barclay James Harvest website plainly states you went to live at the Preston House. This is, of course, a way of not stating that you were invited to live with them, correct? After all, one does not just move into someone else's house unasked, especially when that house is being occupied in a business arrangement.

Godfrey: I was introduced to BJH by Peter Jenner and Andrew King (Blackhill Agency) who had been Pink Floyd's original managers and who had recently become BJH's agents. I met them at London's Roundhouse in 1968. I went out of way to keep in touch with the band whenever they came to London. I was invited to assist with the recording of "Brother Thrush," the band's second single, on which I played keyboards and assisted with the arrangement of the vocal harmonies. It was here, at Abbey Road Studios, that I struck up a good relationship with the band's producer, Norman Smith (ED NOTE: also the Beatles' engineer). After that, I was invited to spend a trial period (one month) with the band in Yorkshire at Preston House to see how we got on. I duly left after the month was up on the understanding that the band would think about everything and get back to me. I went to stay with my parents in Devon and waited. Eventually, the band got in touch with the good news that I was to go and live with them in Preston House and begin work on their first album.

PSF: The website also conflates your being 'Resident Musical Director' with that move.

Godfrey: This is, of course, foolish. One needn't move in with a group to work for it. The term ‘Resident' here is not professionally otherwise taken to mean a rental ‘resident' but rather a person who professionally ‘resides' within some aesthetic context. That would be the standard interpretation, inside or outside your particular situation with BJH, would it not? The "resident musical director" label emerged when the sleeve notes to Barclay James Harvest were being created. I suggested it.

PSF: Were there any terms attached to your moving in?

Godfrey: Except that I would have to live and breathe "as they did," none.

PSF: Who did the asking: the group, an individual member, or John Crowther?

Godfrey: It was actually Les Holroyd who phoned me at my parents and asked, but it was clearly on behalf of the whole band and with the manager's blessing. John Crowther was more a sugar daddy than a manager; he was a local lad made good who had made a great deal of money out of clothes. He had very little time for the actual management of the band. The band was his hobby. I always had a good relationship with him; he took me on holiday with his wife to Wales and he drove me (in his Ferrari) to Europe to see the band play in Belgium and Holland.

PSF: The site claims you were desirous of becoming a full-time member of BJH.

Godfrey: I was and said so. It made sense to me.

PSF: That being the case, was it a realistic ambition, and did anyone in the group encourage it?

Godfrey: Yes, Holroyd and Pritchard were very much in favour. I never knew Lees' view.

PSF: Why would the site claim that Crowther had sentiments against your joining the ensemble? What had he to do with group decisions regarding their own roster?

Godfrey: Crowther had no strong opinions of this kind and took a pragmatic approach, as you would expect.

PSF: The BJH site also claims your aspirations were at the bottom of everything, that they created the tensions and disagreements, which, of course, inferentially makes you out to be a neurotic. What was the bone of contention between you and the group, if any: just the claimed membership issue or matters beyond that?

Godfrey: I am not neurotic. I think I was just too strong medicine for them. Quite apart from the fact that I was an upper class southerner and openly gay, I was also ambitious and had a vision of where we could take the band. I think that the band found this intimidating - so, yes, it caused divisions. Wolstenholme was vehemently opposed to the extent that he said he would leave if I was admitted to the band. That was that, at least for the time being and I accepted it.

PSF: There is an interesting aspect to the site's recitation of the aspiration to membership. It carefully extricates that clause from the previous verb "claims," which creates an ambiguous situation: the reader cannot be sure whether you were indeed regarded by the group as a fifth member, which would have been well justified, or whether you were claiming that you were regarded as a fifth member. It's one of several places in the article in which it looks as though either a lawyer was at work or the writer was grossly inelegant in placing phrases and clauses correctly. My guess would be that it was a lawyer, in full knowledge of exactly the ambiguity that was being created, though I can't definitively know that. What was the true situation here? Had BJH ever claimed you, in any context, as their fifth member?

Godfrey: In the end, the matter of my membership of the band was fudged. I could be called "the fifth member" George Martin-style, but I could not be part of the band's live appearances or officially a band member. I was led to believe that if and when success came, I would be remunerated as if I were a member and share equally with the band in those fruits. That is why I continued to put so much effort in. At my own request, I was described as "the fifth member" on the concert programs for the 1970 tour with the orchestra. The band made no objection.

PSF: The site claims you had "a row" with John Crowther, their manager, and that Crowther paid you 100 pounds to leave. Normally, a dismissal would be done by those who had asked you to move in: the group. Had the group ever asked you to leave?

Godfrey: I had no row with John Crowther at any time. He wasn't the rowing type. Nevertheless, it became clear to me that a decision had been taken to get rid of me. I much later had it confirmed to me by Wolstenholme that it was a decision obtained by the two girlfriends who dominated the band behind the scenes in a way that made Spinal Tap seem quite sensible. I had fallen deeply in love with the future Mrs. Holroyd's brother, and, though there was nothing remotely improper occurring [he was under 21], there was the inevitable talk which had culminated in a show-down with the boy's mother, with me setting the record straight. The scene was now set for my demise.

The band stopped communicating with me and I knew it would not be long. Eventually, John Crowther came to see me and told me that the band wanted to change direction, that the orchestra had been a costly failure which he could no longer support. I should look for another opportunity. He gave me a hundred pounds because he knew that none of us had any money and that I would be unable to move away without some support. He was very nice about it. I asked him about royalties from my work, and he promised me that if the band ever actually made any money, I could expect my share. It would not be long before Crowther was dead, thus making it impossible to confirm this version of events.

PSF: Were there any conditions written anywhere on the check from Crowther?

Godfrey: None.

PSF: Did you ever sign any contracts with the group? If so, may I see copies of them? I'd like to inspect the language.

Godfrey: I signed none.

PSF: That you might have had personal differences with the group seems to be internally contradicted by the site as it proceeds to show that you were friendly with BJH, that you saw them at the Cambridge Corn Exchange and "chatted amicably." This is just one of "several" contacts, according to the site. I needn't repeat that the article is exceedingly vague and confusing in its own terms (the writer is himself confused about when that meeting occurred: 1974 or 1975), but what was the state of your friendship with the members at this point?

Godfrey: This is true. I think by then it was a matter of kiss and make up. However, I remember an occasion not so long before that when I had to be called in by Wolstenholme to conduct my arrangement of his "White Sails" at University College London because Martin Ford wasn't up to it. None of the rest of the band would speak to me! The fact is that although Wolstenholme was initially opposed to me joining the band, he later realised that I was an asset and a true source of inspiration. He had done his best to have me recalled to duty, knowing full well that Martin Ford was inadequate and opportunistic. I remained friends with him until the court case which, to my dismay, killed it off completely.

Putting it bluntly, Woolly was the only one of them who had any brains and a mind of his own. He was able to see what Norman had meant when he told us all that if we stuck together, we would be as successful as Pink Floyd. Wolstenholme left the band himself not long after. I invited him to join The Enid. He thought about it seriously. I would still have him if he wanted it.

PSF: You, on your Fall of Hyperion LP, claimed Wolstenholme as a "musical confessor." That seems a bit odd, given that you're a vastly more accomplished composer than he. What were you referring to when you called him a "confessor"?

Godfrey: Irony, dear boy. It was of course the other way around!

PSF (chuckles): Do you still view Wolstenholme as a special individual? Do you still see Lees, Wolstenholme, or Holroyd on a friendly basis?

Godfrey: I sowed the seed of a higher sensibility to art and music in Woolly, and the course of his life has been deeply affected by his one-time friendship with me. I would see Woolly if he would let me, and I am truly sorry for the fracture caused by the court case. I believe the other two hate my guts - largely out of guilt and a repressed shame, I do not doubt.

PSF: The BJH site claims you issued writs against them, based on "breach of contract" and other charges. What contract had been violated, a written one, an oral one, an implied one, or...?

Godfrey: These preceding were drawn up by my lawyers who decided what the grounds should have been according to the statement I made to them. The contract was an oral one established by the performance of it over two years. I lived as they lived, with no wage and no fees, just a similar subsistence supplied by John Crowther.

PSF: The site uses peculiar wording regarding breach. It says you alleged 'breach' or additional payment. It may be just a boneheaded statement but, if not, it's confusing, perhaps purposely so. One does not allege "additional payment," one alleges bad conduct that might involve additional payment as remedy.

Godfrey: The conjunction ‘or' is also important here: it means that the writer was not very familiar with what he or she was talking about.

PSF: Yes, as I suspected. What precisely is being referred to: one action, two, or more?

Godfrey: There were two actions: one for copyright infringement and one for breach of contract because there was an implied contract between myself and the other band members with regard to the way I was to be remunerated.

PSF: The site claims that the court notes that "there was no common understanding" re: a share in the band's earnings. This is vague.

Godfrey: The court did not accept that there was a common understanding. In other words, what I understood was not what they [the band] understood.

PSF: As so damn much centers in it, I'd like to risk redundancy and iterate this point. The claim of lack of an "enforceable agreement" seems to say there was no contract but does not say so precisely. Did, in the court's eyes, any contract exist at any point, enforceable or otherwise? Crowther was a businessman; surely he knew about contracts as a way of conducting ethical business?

Godfrey: Crowther's death prevented the court from being able to establish any facts one way or the other because the band always referred any matters of my "employment" to Crowther, knowing that it would be my word against that of a dead man. The band would not say whether there was a contract or not, only that John Crowther would have dealt with my relationship to the band.

PSF: Interesting... interesting. The site claims you had "varying degrees" of agreement of authorship adjudicated from Judge Blackburne. It stays curiously silent on two songs and claims the judge saw authorship as "very borderline" on two. This is suspiciously slanted, their, the site and author's, words, not the judge's. At no point is any quote from the judgement on this explicitly given by the site. What is the judge's exact wording? Do you have a copy of the judgement? May I obtain a duplicate?

Godfrey: I no longer have a copy of the judgement. I lent it to someone with whom I have lost contact. I think this is the position: I was required to state my involvement with any composition in which I had participated, however slight; any omission would have been used against me as a matter of "Why is Mr. Godfrey claiming authorship in this particular piece when it is clear that he participated (to some degree) in some other work for which he has made no claim?"

PSF: Odd. Well, the only time the site does quote the judge is when the judge's words appear to suit its purpose, especially referring to his sentiments about the timing of your claim. The wording is: .".. the success which the band later achieved and which led the plaintiff to decide that it was at last worth his while to pursue his claims was the result of many years of hard work, considerable self-sacrifice and much expenditure. It would be against all conscience if, in these circumstances, the plaintiff should be permitted to step in and reap for himself a share of the band's hard-earned success. In my judgement, the plaintiff is estopped from claiming any relief to which he might otherwise have been entitled."

This is strange jurisprudence. I'm quite sure the American and British legal systems are not duplicates, but intelligence, sense, and justice lie beneath both, so it must be noted that the judge seems extraordinarily short-sighted and ignorant in his remarks. Whether or not the band worked hard to earn success is moot in the face of intellectual property questions, the very foundation without which that hard work was meaningless. The labor lays atop, not beneath, the property; that is, the band's success could not be achieved without a property to achieve it upon. Claiming their hard work rightly denies you access to monies owed from the very authoriality the judge agrees you share, thus helping ensure those riches, is either shockingly bizarre, grotesquely mistaken, or maliciously wrongheaded, perhaps all in combination. Have you not attempted to appeal the judgement or is that not allowed in England's justice system? It appears to me that there is a VERY fundamental mistake, at the very least, by the judge, which I would hope law, precedent, or, especially, appellate finding would reverse.

Godfrey: In fact, in a more recent trial involving Mathew Fisher and Procol Harum in which my trial was used as a precedent, a similar judgment was eventually overturned by the House of Lords.

PSF: How terribly typical of juridical irony. The conclusory quote from the judge, "I dismiss the two actions," is also striking. In America, when a suit is dismissed, there is no trial, and the judge could have made no findings nor issued a decision, much less a 52-page one, as Judge Blackburne had here. What does the British legal term ‘dismissed' mean?

Godfrey: It means that the judge can make findings of fact during a trial but can still dismiss an action on legal/technical grounds after hearing all the evidence (such as laches).

PSF: Hmmm. Your legal system certainly contains very different procedures from ours. The site says you claimed you "had been cheated out of royalties and credits." Who did you claim did the cheating? The site's very careful to exclude almost any reference to the band's labels, keeping this as much as possible to a personal conflict. What was the label's part in all this? You, on your site, speak well of BJH but mention the label more than once, as interferatory and vindictive after the judgement.

Godfrey: The labels promised in writing before the trial that they would make sure I was credited as the composer of these works if there was any finding at all by the court that I was. They then hid behind the apparent contradiction of my having lost the case.

PSF: Well, mercantiles are nothing if not mercenary. I'm amused by the BJH site's use of the clause about the main points of the judgement: "which can be summarised as follows." Even a lowly desk clerk for a law firm knows about weasel verb phrases like "can be": they're meaningless and point to an unwillingness to reproduce the pertinent points in exactitude. That the article itself credits no author is equally amusing, as writers are as zealous of their rights and credits as musicians. Do you know who wrote this "Robert John Godfrey and Barclay James Harvest" article on their website?

Godfrey: No.

PSF: Too bad; I'd like to know which of my inky "brethren" was so callow. The final site paragraph is fairly monstrous. Besides clearly showing, as much as it does not want to, the justice and rectitude of your claim(s), which the group and label fervently fought for decades, it takes a final shot at you by attributing an apparent nervous breakdown suffered by Wolstenholme to the action, silently inferring you as the agent of the malady, since you'd initiated the suit. Again, as in several places, the writer is careful not to say these words exactly, but the imputations are egregious, all the more so by a firm refusal to say what, if not your action, had precisely caused the alleged breakdown. The writer makes sure the attribution of "as a result" closely follows the fact that the suit apparently cost Wooly and the others a great deal of money. Did Wolstenholme in fact suffer a diagnosed nervous breakdown? If so, what was shown as the cause?

Godfrey: I have no idea. Woolly did not appear at the trial. He was the only one to admit in his written evidence that the band had indeed received a solicitor's letter from me in 1972 putting them on notice that I had a potential claim. I do know that he was worried about the outcome of the trial. I heard that he felt aggrieved that he had been dragged into this conflict when he had had no real contact with the band since he had left in the seventies. I also know that Woolly would not have been prepared to go to court to tell lies under oath as some of the others did; the judge made it quite clear in his oral judgment just what he thought of some of their sworn evidence. I suspect that this breakdown, real or not, proved a very convenient event in Wooly's life.

PSF: Here is a truly weird sentence: "So, the final outcome was that Robert Godfrey got nothing from the actions, having left it too late to pursue his claims." Firstly, that's patently a lie. You finally received legal recognition of your authorship and, by implication, shared intellectual property. That's a great deal more than "nothing." Also, the pronoun "it" has no proper antecedent: its use infers the "actions," but that would mean the pronoun should have been "them," reflecting number properly, not "it," and thus the choice of "it" can only have one other antecedent: "the final outcome," which is plainly bizarre, nonsensical. The article then goes on to twice deny your victory, saying "nobody won," throwing everything on the rhetorical straw man of lawyers: "no one won except for the legal profession" - which, of course, you had invoked, you evil Satan you. After all, how dare you fight for your rights? Oh, wait a minute, wasn't that precisely the sort of thing BJH challenged its listeners to do consistently, on a number of their songs, on many albums?

Godfrey: Are you being rhetorical?

PSF (chuckling): It's a personal trademark. Then, of course, there's the essay's parting shot, "that's all water under the bridge now," an attempt to display BJH as philosophical about the entire action and its outcome... after plainly, mindfully, and vigorously attempting to destroy it for more than two decades. On its bare face, the site's writer seems to be incredibly incompetent or purposely obfuscatory. This whole article should be extremely repugnant to BJH fans, who would have to carry a sense of justice merely by the virtue of having taken in the group's (obviously hypocritical) words for so many years regarding such things. On the other hand, as can be seen in the genre's prolific magazine letter columns and such, genre fans, though they may have quite excellent tastes in music, don't seem to have cultivated a tremendous amount of intelligence beyond that. Thus, this sort of hideous bullshit is allowed to stand without comment. You'd think there'd be a trifle more discernment behind all this from somewhere, wouldn't you?

Godfrey: Rhetorical again?

PSF: But of course!