IVOR DARREG AND XENHARMONICS

(original article from October 1997)

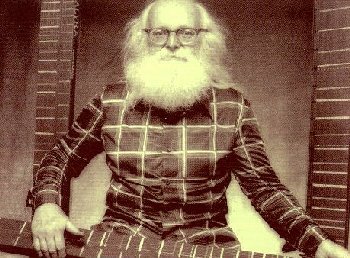

Biography by Jonathan Glasier

Ivor Darreg was born Kenneth Vincent Gerard O'Hara in Portland Oregon. His father John was editor of a weekly Catholic newspaper and his mother was an artist. Ivor dropped out of school as a teenager because he had a series of illnesses that left him without teeth and with very little energy. He did have energy to learn. He was self-taught in at least ten languages that he read and spoke. He had a basic understanding of all the sciences. His real love was music and electronics. Because of his choice of music, his father cast him out and he and his mother set out on their own with little help from anyone. At that point he took on the name "Ivor," which means "man with bow" (from his cello-playing talents) and "Drareg" (the retrograde inversion of "Gerard"), soon changed to Darreg.

Ivor's life with his mother was a huge struggle, and Ivor's health was poor until his mother died in 1972. Part of the reason was that they lived on canned soup, and the salt kept his blood pressure sky-high. Being poor in health and wealth, Ivor became resourceful. He picked up stray wires that were cut off telephone poles and other things on the street and from friends. He said he learned to "pinch a penny so hard, it would say ouch." Ivor created his first instrument, the Electronic Keyboard Oboe, in 1937. Following the current history of electronics and reading from the journals of the day, he learned circuitry. He made the instrument, which still runs today, because the orchestra he was playing in needed an oboe and Ivor took the challenge. The Electronic Keyboard Oboe is not only one of the first synthesizers, but a microtonal one at that. It plays the regular twelve tones, but there are eight buttons that move the tone in gradation from a few cents for a tremolo effect to a full quarter-tone.

In the forties, Ivor built the Amplified Cello, Amplified Clavichord and the Electric Keyboard Drum. The Amplified Clavichord no longer exists, but the Electric Keyboard Drum, which uses the buzzer-like relays, and the Amplified Cello are still working.

In the sixties Ivor created an organ with elastic tuning. The circuitry would justify thirds and fifths. In the early sixties, Ivor met Ervin Wilson and Harry Partch. Upon conversing with Wilson and seeing his refretted guitars and metal tubulongs (3/4" electric conduit), Ivor took the plunge into non-quartertone microtonality or Xenharmony. He began refretting guitars and making tubulongs and metallophones in 10, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22, 24, 31 and 34 tone equal temperaments. He shared his new beginning with others through his Xenharmonic Bulletin and other writings. The Xenharmonic Alliance [a network of people interested in alternative tuning systems] was created. When we met Ivor in 1977, through John Chalmers, I saw a need to give Ivor and others a more public forum, so I started the journal Interval/Journal of Music Research and Development. Then in 1981, Johnny Reinhard created the American Microtonal Festival in New York, and in 1984 the 1/1 just intonation group started in San Francisco. Recently the South East Just Intonation Center has been created by Denny Genovese.

In the seventies, Ivor created his Megalyra family of instruments, the Megalyra itself being the tour de force of Ivor instrumental creations (featured in EMI Vol. II #2). This six to eight foot long contrabass slide guitar is strung on both sides to solo (I-I-V-I) and bass (I-V-I) configurations. This instrument sounds like tuned thunder and is waiting for some heavy metal or slide guitar pro to make it a celebrity. Other instruments in the Megalyra family are the Drone, Kosmolyra, and the Hobnailed Newel Post, which is a 6" by 6" beam strung with over seventy strings. Ivor called this instrument his harmonic laboratory.

Those of you who knew Ivor or read his writings knew that he had a special outlook on music, and a comprehensive mind that explored many subjects. His compositions, of which all are either on tape or written down, date from 1935. Many of his piano compositions are available on cassette, played by Ivor. Detwelvulate! contains a selection of his tapes Beyond the Xenharmonic Frontier, Vols. 1, 2 and 3 as well as earlier acoustic recordings Ivor made on his reel-to-reel machine (see the end of this article for more information).

Elizabeth and I brought Ivor to San Diego in 1985, and he seemed to get younger every year. He was in the best health of his life for those years. We were very happy to be there to share time with this great man and friend, and see him spend the most productive and stable years of his life here in San Diego.

We miss you Ivor.

Ivor Darreg

NEW MOODS

[From Xenharmonic Bulletin No. 5, 1975]

The time has come for me to share an important discovery with other composers, and some of you who are interested in performing or adapting existing music to new tuning-systems might like to join in. In my opinion, the striking and characteristic moods of many tuning-systems will become the most powerful and compelling reason for exploring beyond 12-tone equal temperament.

It is necessary to have more than one non-twelve-tone system before these moods can be heard and their significance appreciated. I urge all of you not to become 'stuck' in any one non-12 tuning-system no matter how excellent it is. To fence yourself in, to stop so soon, is just as bad as to remain obstinately wedded to 12-tone equal.

These moods were a complete surprise to me- almost a shock. Subtle differences one might expect- but these are astonishing differences.

The available literature dealing with non-twelve-tone scales is heavily theoretical. Under such circumstances, it is not too surprising that certain aesthetic and emotional aspects of music have been overlooked or de-emphasized. In consequence, many persons who should be participating in the xenharmonic movement have been 'turned off.'

We shouldn't allow this situation to get any worse. During the last eleven years or so, that is, since I started composing and performing in such scales as 17-, 19-, 22-, and 31-tone, I have become more and more aware of the characteristic moods of those systems, and later on, of the characteristic mood of the ordinary 12-tone system as well.

That is to say, you only become aware of your environment after leaving it and then returning to it- or to use McLuhan's bon mot, "the fish is not aware of the water."

You will notice that I did not include the quartertone or 24-tone system up there. I left it out intentionally on purpose. 24 is twice twelve, and the quartertone mood, while it does exist and is a most useful mood to have, is both underpinned and held back by the twelve-tone mood, so that no matter how many quartertone intervals you use in your compositions, you have not escaped the 12-tone mood and are still its helpless slave. The quarter- and sixth-tone works of Haba, Carrillo, et al., are evidence enough of what I am talking about here.

Since one cannot anticipate the emotional and aesthetic effects of a system before building or modifying instruments to play in it, and since there is nothing in the mathematical theory of tuning to suggest or hint at or indicate that certain temperaments will have novel general effects, I find myself in the uncomfortable position of having a monopoly that I want to get rid of!...

...Such systems as 10-,11,-16-, and 23-tone are not likely to have much key-feeling about them. However, `dollars to doughnuts' they are going to have decided moods in which some serial and atonal music is going to be more exciting than any 12-tone serialism!

I could explain here that the seventeen-tone system turns certain common rules of harmony upside-down: major thirds are dissonances which resolve into fourths instead of the other way round: certain other intervals resolve into major seconds; the pentatonic scale takes on a very exciting mood when mapped onto the 17 equally-spaced tones, and so on; but I can't expect you to believe me until you hear all this yourself. If you try to play these pieces in another system, it just doesn't work; they lose their punch; the magic is all gone.

Quite as much, if not more as, when certain pieces composed in and for 19 are tried in 31. They go flabby, no punch. On the other hand, certain pieces composed in 31, when tried in 19, become too crude or coarse-textured. They lose their finesse, their subtlety, and the restful calm of 31 is replaced by the aggressiveness of 19...

...Few of the experimenters in non-12 instruments have had the money, time, or patience to build or have built instruments in more than one non-12 system. Only very recently has it become practical to compare, say, 17 with 19, or 22 with 31, on a fair and realistic basis. It has always been 12-tone compared with something else- some one thing else.

The motivations have been to secure smoother conventional chords, hence just intonation or that close imitation, 53-tone; or to get restful major thirds, hence meantone or 31-tone or one of the numerous 'unequal' or incomplete systems. The motivations for quartertone and some other systems have been to enlarge the vocabulary without having to scrap 12 tone, and similar obvious reasons.

When I started out as a teen-ager, I learned to play the cello so that I could find the quartertones and hear them, and later, sound just major thirds and sixths- all of which annoyed my cello teacher no end! I knew nothing then about 19-tone and its mood, and since you can only play two sustained tones at a time on a bowed instrument, I did not hear sustained just triads or tetrads for quite some years to come. I did persuade someone to let me tune their piano to a just scale, but that was not a necessary or sufficient test- the very factors which make the piano tolerable in the 12-tone temperament conceal the possibilities of just intonation.

Anyone who has invested money, time, and effort in one non-twelvular instrument is not likely to have enough left over to go on and compare a 19-tone organ with a 22-tone one or anything of that sort, so these mood-differences as between 17 and 19 or 19 and 22, or the nature of the ambivalent relation between 19 and 31, have not been explored. Instead, the comparisons have been in silent numbers on paper.

Furthermore, the difference in mood between 12 and some of these others such as 19 or 31 is so profound and striking that I can't blame anyone for feeling that they need not explore further since they have a good instrument in such a system. One who is stuck with a heavy investment also and quite naturally will feel that he has to defend his agonizing choice. Again naturally, this will determine and influence their line of argument. They will choose this point and ignore that one, to make a good case for 22 against 19, or for 19 against 22, or whatever. When so much as been invested, one can no longer be objective!

Maybe there is some better term than mood; your suggestions are invited as soon as you have heard the effect of the different tunings. Hitherto, comparisons of systems have been made on a basis of How closely does this system come to just intonation? How many tones does it need? How strange or awkward a keyboard does it require? Does it require special notation-signs, and if so, how many? Is it compatible with existing printed music? Can it be tuned with the standard organ or piano-tuning routine?, and on and on the critics go with their endless restrictions and demands- what I have quoted above is already too much, since no system comes near to meeting all of them...

Now we can choose from a tremendously large array of systems and even change systems during a performance, as those interested in older or not-as-new music can experiment and find the right mood for everything... I think the common-sense thing to do is for somebody to run through a large number of system-and-timbre combinations with a bank of computer-controlled synthesizers to make a reference tape.

It will take the co-operation of many persons for quite some time to come to map out the vastness of xenharmonic territory.

Enormous thanks go out to >David Beardsley who introduced us to Ivor's music.

Also see our 2022 article on Ivor Darreg

MAIN PAGE

ARTICLES

STAFF/FAVORITE MUSIC

LINKS

WRITE US