Iannis Xenakis:

the aesthetics of his early works

Photo courtesy of Xenakis World

by Markos Zografos

The 1950's marked an extraordinary era of music experimentation and development in the current of emerging European composers. Amongst these, Iannis Xenakis would begin to compose his first mature works. He would reject the avant-garde trend of serialism and build his own aesthetic principles founded in the world of abstract mathematics, which, amongst other things, applied a unique philosophy of 'chance' to music. The style of music which arose from these principles he labeled 'stochastic music,' and the first two works which arose in this style, "Metastaseis" and "Pithoprakta," set the foundation of his aesthetic principles that he would go on to develop and experiment with for the rest of his musical career. In assessing how Xenakis came to use aesthetics grounded in abstract mathematics one must examine his early life prior to mature music composition. This involves examining his childhood, education, influences and experiences with the Second World War.From an early age it seems Xenakis had been mapping out his intelligence and capabilities as though for his benefit alone.1 He recalls, in a 1987 article, that at around twelve or thirteen years of age he would be practising piano, reading about astronomy for hours on end and studying mathematics and archaeology. 2 He confidently disdained schoolwork in favour of his own personal reading, and left school at the age of sixteen without any distinguishable academic record. 3 It was at this time, in 1938, that he enrolled in the Athens Polytechnic to study engineering, where he undertook courses in mathematics, physics, law and ancient literature. 4 He also took up studying harmony and counterpoint with Aristotle Kondourov "who impressed upon Xenakis the necessity of absolute rigour and discipline in the pursuit of composition." 5 Therefore the assimilation of interests that shaped his aesthetic principles in music, namely those of mathematics, physics, astronomy and ancient literature6 can be traced back to his early years of education, and his highly disciplined approach to formalizing music can also be traced back to his first formal music lessons with Kondourov in these years.

Study at the Polytechnic was to be abandoned in 1940 with the Second World War affecting Greece. It would take Xenakis another seven years to finally graduate with his diploma of engineering. 7 During these years, Xenakis would mostly involve himself as a Communist resistance fighter against the Germans, who had occupied Greece, and he was frequently involved in mass resistance demonstrations, often finding himself in prison as a result. At the end of those seven years, in November 1947, Xenakis illegally fled to Paris where his diploma of engineering landed him work with the famous French architect Le Corbusier. 8 In an interview Xenakis spoke of Le Corbusier's influence on his creative thought:

It was the first time I had ever met a man with such spiritual force, such a constant questioning of things normally taken for granted. I knew a good deal about the ancient architecture and that had been enough for me; he, on the other hand, opened my eyes to a new kind of architecture I had never thought of. This was a most important revelation because quite suddenly, instead of boring myself with mere calculations, I discovered points of common interest with music, which remained, in spite of all, my sole aim. Up to then my architectural and engineering work had been done to gain a crust, but thanks to Le Corbusier I had now found a fresh interest in architecture. 9Evidently, Le Corbusier and the influence of architectural work gave Xenakis impetus to apply a visual approach to music by applying the technical facilities inherent in architectural design to the same plateau as music design.

This technical grounding was further encouraged by Messiaen, composer and then lecturer in musical analysis at the Paris Conservatoire, with of whom it was suggested by Le Corbusier that a meeting should take place between the two. At that point, Xenakis was becoming disillusioned by other teachers of composition, namely Milhaud and Honegger, who assessed Xenakis' compositions with complete stubbornness. 10 Not until he approached Messiaen after an analysis class did Xenakis finally attain a clear directed response of the path in which he should take. Xenakis basically asked Messiaen whether he should wipe his slate clean and begin studying harmony and counterpoint again, but Messiaen surprised Xenakis, as Messiaen himself recounts:

I did something horrible which I should do with no other student, for I think one should study harmony and counterpoint. But this was a man so much out of the ordinary that I said... No, you are almost thirty, you have the good fortune of being Greek, of being an architect and having studied special mathematics. Take advantage of these things. Do them in your music. 11Although Messiaen and Le Corbusier acted as final catalysts in assuring Xenakis' mature compositional style to be born, the impact of the war definitely marked itself on him, as it did with all composers at that time. As Elisabet Sahtouris wrote, in her 1998 article "The Biology of Globalization," "some of the greatest catastrophes in our planet's life history have spawned the greatest creativity" 12; this would hold true as a result of the highly experimental compositional climate that came about in Europe during the 1950's. The Second World War definitely impressed itself on European composers of this period.

It was more than an emotional and psychological upheaval, living through the war. Everyone had recollections, images, experiences and impressions involving the different senses, but especially recollections of extraordinary sounds heard during air raids, sirens, explosions, bombing. A person suffering from shock is often more acutely disturbed by sound than sight. Several composers, among them Stockhausen, Berio, Xenakis, report detailed accounts of aural phenomena which have remained with them twenty years after the experience. The war had accustomed them to a sound world which had never seemed possible before and each one had to adjust to it in his own way. This assimilation took many forms, it explains why, for instance, musique concréte was so quickly accepted by this generation as a perfectly natural extension of the sound continuum they had perceived, and secondly, the violence, anger and horror of the war could be transformed into a music which was openly aggressive, brutal and violent. 13The war experience was to leave a profound effect upon Xenakis' music and intertwining creative thought. He illustrates this in a passage from his 1971 book Formalized Music which explains the sonic events of a demonstration march where rhythmic, uniform shouting of slogans graduates to chaotic screaming as the enemy opens fire:

Everyone has observed the sonic phenomena of a political crowd of dozens or hundreds of thousands of people. The human river shouts a slogan in a uniform rhythm. Then another slogan springs from the head of the demonstration; it spreads towards the tail replacing the first. A wave of transition thus passes from the head to the tail. The clamour fills the city, and the inhibiting force of voice and rhythm reaches a climax. It is an event of great power and beauty in its ferocity. Then the impact between the demonstrators and the enemy occurs. The perfect rhythm of the last slogan breaks up in a huge cluster of chaotic shouts, which also spreads to the tail. Imagine, in addition the reports of dozens of machine guns and the whistle of bullets adding their punctuations to this total disorder. The crowd is then rapidly dispersed, and after sonic and visual hell follows a detonating calm, full of despair, dust and death. The statistical laws of these events, separated from their political or moral context... are the laws of the passage from complete order to total disorder in a continuous or explosive manner. They are stochastic laws. 14The mathematical makeup of these 'stochastic laws' were to become principal features in the compositional development of Xenakis' first mature works, "Metastaseis" (1953-54) and "Pithoprakta" (1955-56). In Formalized Music, Xenakis labels this music 'Free Stochastic Music' where the movements of microscopic parts (in orchestration a 'microscopic part' is represented by a single instrument) are subservient to the macroscopic whole which governs the microscopic parts through deterministic tendencies. Peter Hoffmann, on the other hand, labels this music 'Macroscopic Stochastic Music' which illustrates this point more clearly than Xenakis' label. 15

The mass 'sonic phenomena' demonstrated in the social disorder of the demonstration rallies definitely created a large impetus of creative inspiration which led to the creation of 'stochastic music,' and which led to many sounds and effects that Xenakis would demand in his musical compositions; however it represents one of a few other crossroads which sufficed this train of thought for him, for immediately prior to the passage about the sonic phenomena of the demonstration crowd Xenakis wrote of 'natural events' that also follow stochastic laws, these being

the collision of hail or rain with hard surfaces, or the song of cicadas in a summer field. These sonic events are made out of thousands of isolated sounds; this multitude of sounds, seen as a totality, is a new sonic event. This mass event is articulated and forms a plastic mould of time, which itself follows aleatory and stochastic laws. 16All the sonic phenomena explained in terms of stochastic laws thus far are examples of 'noise', which is a key sonic feature in most of Xenakis' compositions (all of them in the 1950's) and also a feature many composers in Europe were exploring at the same time (one that Edgar Varèse pioneered in terms of traditional instrumental writing). However, the formal methods for ordering the sonic state of 'noise' between Xenakis and his European contemporaries were highly different. Where a trend amongst European composers was taking serialism to its most extreme manifestation in a total serialization of a number of the musical elements, this was attacked by Xenakis in his 1954 article "The Crisis of Serial Music." In this he commented that in serial music "linear polyphony destroys itself by its very complexity" producing "nothing but a mass of notes in different registers" and also noted the contradiction between the "deterministic causality" of serial methods and the actual effect of "an irrational and fortuitous dispersion of sounds over the whole extent of the sonic spectrum." 17 This article, however, was not so much an attack on serial music as much as it was a boost for his own compositional aesthetics. As he wrote in Formalized Music, "this article served as a bridge to my introduction of mathematics in music." 18

As much as his rejection of serialism as unsuitable for his compositional objectives, Xenakis also rejected the John Cagean manifestation of chance music as he remarked in an interview, "for myself this attitude is an abuse of language and is an abrogation of a composer's function." 19 John Cage first applied the fundamental philosophical principle of chance to music, that is, "to remove from music any reference to tradition or any trace of subjectivity." 20 In his lecture Indeterminacy, Cage stipulates this point very precisely:

Finally I said the purpose of this purposeless music would be achieved if people learned to listen; that when they listened they might discover that they preferred the sounds of everyday life to the ones they would presently hear in the musical program; that that was alright as far as I was concerned. 21When an interviewer asked Xenakis why he avoids using fortuitous sounds in his compositions, Xenakis promptly answered, "we all have fortuitous sounds in our daily lives. They are completely banal and boring. I'm not interested in reproducing banalities." 22 He went on to attack the various forms of chance music that he was aquainted with, each originating from the Cagean frame of mind:

The assumption that removing certain constraints from a performing situation frees the player and audience from learned responses and habits was rejected by Xenakis who asserted that on the contrary the player was likely to fall back on his habitual conditioned behaviour or merely oppose it in the most superficial way under pressure of performance. To equate chance with the suspension of responsibility by the composer in the name of freedom was illusory. He also noted that composers never relinquished their authorship over performances despite claims made in the name of chance which smacked to him not only of inconsistency, but piracy. 23It was nothing new to encounter chance in a different way from John Cage amongst European composers in this period. Contemporaries like Boulez and Stockhausen also explored chance differently from Cage in this decade, "where the performer is placed in a position to make spontaneous or rehearsed decisions about the ordering of the music." 24 Xenakis' fundamental approach to chance, however, differed in that it applied reason and order to 'controlling' chance the most progressively it possibly could with the knowledge available at that time in the field of science and mathematics. This is stated in Formalized Music:

Since antiquity concepts of chance, disorder and disorganization were considered the opposite and negation of reason, order and organization. It is only recently that knowledge has been able to penetrate chance and has discovered how to separate its degrees - in other words to rationalize it progressively, without, however, succeeding in a definitive and total explanation of the problem of 'pure chance'. 25

Therefore Xenakis' eagerness to embrace chance and chaos and try to understand what role these concepts play in our world led to what role they could play in the creation of his music.

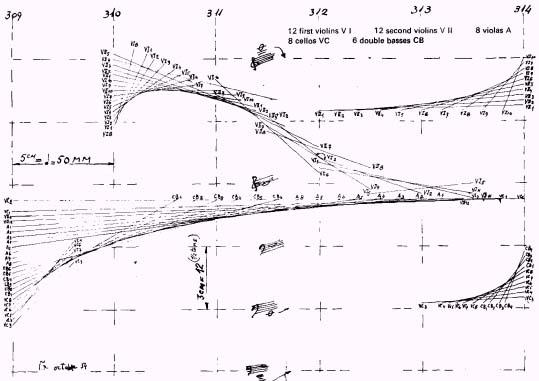

In "Metastaseis," Xenakis confronted most of the fundamental musical problems and in effect "Metastaseis" presents the foundation for the style and aesthetics he would follow through for a good deal of his musical career with the concept of textural sound composition. In his 1954 article "Les Metastaseis," Xenakis describes this concept: "the sonorities of the orchestra are building materials, like brick, stone and wood... the subtle structures of orchestral sound masses represent a reality that promises much." 26 Le Corbusier's influence and architectural work was prominently realized in "Metastaseis" as the original plotting of the massed glissandi were done on the same graph paper that was used for plotting building structures. This reflects Xenakis' idea of a musical 'space-time', where pitch is represented on the y-axis and time on the x-axis. 27 "A two-dimensional space is created where potentially time-independent musical structures can be contained in a temporal setting." 28 He later used plotting of string glissandi in "Metastaseis" as the curvature for the walls in the Philips Pavilion (constructed for the 1958 Brussels World Fair).

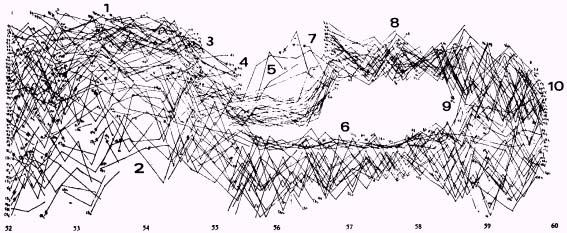

The massed moving formations of string glissandi and 'brass in total disorder', as Xenakis describes, that occur in "Metastaseis" and later in "Pithoprakta" relate to the kinetic theory of gases. 30 This theory states that "the temperature of a gas derives from the independent movement of its molecules." 31

Xenakis drew an analogy between the movement of a gas molecule through space and that of a string instrument through its pitch range. To construct the seething movement of the piece, he governed the 'molecules' according to a coherent sequence of imaginary temperatures and pressures. The result is a music in which separate 'voices' cannot be determined, but the shape of the sound mass they generate is clear. 32While in "Metastaseis" Xenakis applied the kinetic theory of gases to organize musical materials, the materials themselves, such as pitch, were acquired via a dodecaphonic row set with time (at the opening) ordered by the Fibonacci series (both common sources for organization amongst European composers at the time), which is why some critics argue that "Pithoprakta" is Xenakis' first truly mature musical composition in a style that acquires all its musical elements through mathematical theories and principles. The concept of 'sound masses' and the textural use of the orchestra (for example glissandi, pizzicati) remain similar in "Pithoprakta", however the musical materials were undertaken purely by using Probability theory ("Pithoprakta" literally means 'actions through probabilities'). In the case of "Pithoprakta," this relates to Jacque Bernoulli's law of large numbers which states that as the number of occurrences of a chance event increases, the more the average outcome approaches 'a determinate end'. 33 Xenakis would still apply other theories and principles in creating the music, such as the theory of gases and Poisson's law of sparse events, which dictates the sparse textures late in the work, but the importance of Probability theory was, according to Christopher Butchers, of vast importance in the blending of science and art. Butchers wrote that "Xenakis is, to my knowledge, the first in any artistic field both to invoke the notion of chance and to use it in a way which is acceptable rigorously to modern logic." 34 This application of chance to 'modern logic' that Butchers assigns comes from a statement made earlier in the article that:

it is the central importance of probability which principally differentiates the science of the twentieth century from that of the past; in that we have moved from the belief that science consists of an ever more exact measurement of ever more precise entities to the belief that knowledge is as valid and comprehensive when it embraces an appreciation of the general characteristics of entities on a macrocosmic plane, the precise properties of those micro-components being irrelevant. 35

Therefore, the style of 'stochastic music' that Xenakis created amidst a wilderness of other experimental trends was to stand out as his own unique entity. Inspired by 'noisy' and/or violent sonic phenomena such as demonstration rallies in the Second World War or the song of cicadas in a summer field, Xenakis applied mathematical theories and principles in assembling the makeup of this music that grounded its sonic principle as textural sound composition. The influence of architecture, where Xenakis also used abstract mathematics as his aesthetic foundation, grounded a means of technical facility whereby Xenakis was able to visualize music graphically from an 'externally-relative' position. Aesthetically, theories such as the kinetic theory of gases and Probability theory became two major standpoints in organizing the musical materials in his first two works "Metastaseis" and "Pithoprakta." These works had assembled the aesthetic means of a mathematically formalized organization of music and acted as the foundation for a myriad of works which were to develop and experiment with these aesthetic means for the rest of his career.

Notes

- Nouritza Matossian, Xenakis, (London: Kahn & Averill, 1986), p. 16.

- Iannis Xenakis, "Xenakis on Xenakis," Perspectives of New Music, vol. 25, no. 1 & 2 (Winter, 1987), p. 18.

- Matossian, Xenakis, p. 16.

- Ibid., p. 17.

- Ibid., p. 18.

- Ancient literature would be of more significant inspiration later in his musical career from the early 1960's onwards, where he would apply names from Ancient Greek tragedies as the titles to his works, and write music set to Greek tragedies (for example Oresteia), thus it is of little relevance in the purpose of this essay.

- Matossian, Xenakis, p. 18.

- Ibid., p. 31.

- Mario Bois, Iannis Xenakis: The Man and his Music: A Conversation with the Composer and a Description of his Works, (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1980), p. 5.

- Xenakis, "Xenakis on Xenakis," Perspectives of New Music, p. 20. In this Xenakis states:

What counted above all was the row I had with Honegger. I was enrolled in his composition class at the École Normale. The students would bring their works, and he would critique them in front of everyone. I went there. I showed him a score. He played it and said,

"There you have got parallel fifths."

"Yes, but I like them."

"And there, parallel octaves."

"Yes, but I like them."

"But all this, it's not music, except for the first three measures, and even those..." And the madder he got, the madder I got. I thought that he was a free-thinking man. How could he make a thing out of parallel fifths, especially after Debussy, Bartók, and Stravinsky? - Matossian, Xenakis, p. 48.

- Elisabet Sahtouris, The Biology of Globalization, available at http://www.ratical.org/LifeWeb/Articles/globalize.html, last accessed 12 August 2002.

- Matossian, Xenakis, p. 45.

- Iannis Xenakis, Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1971), p. 9.

- Peter Hoffmann, "Iannis Xenakis," The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. 27 (London: Macmillan, 2001), p. 608.

- Xenakis, Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition, p. 9.

- Robert P. Morgan, Twentieth-Century Music, (New York: Norton, 1991), p. 392.

- Xenakis, Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition, p. 8.

- Bois, Iannis Xenakis: The Man and his Music: A Conversation with the Composer and a Description of his Works, p. 12.

- Paul Griffiths, "Aleatory," The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. 1 (London: Macmillan, 2001), p. 346.

- Ibid., p. 346.

- Khai-Wei Choong, Iannis Xenakis and Elliott Carter: A Detailed Examination and Comparative Study of Their Early Output and Creativity, (Brisbane: Griffith University, 1996), p. 32.

- Ibid., p. 32.

- Griffiths, "Aleatory," The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, p. 342.

- Xenakis, Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition, p. 4.

- Hoffmann, "Iannis Xenakis," The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, p. 607.

- Ibid., p. 607.

- Ibid., p. 607.

- Xenakis, Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition, p. 3.

- Hoffmann, "Iannis Xenakis," The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, p. 608.

- Ibid., p. 608.

- Choong, Iannis Xenakis and Elliott Carter: A Detailed Examination and Comparative Study of Their Early Output and Creativity, p. 36.

- Paul Griffiths, "Xenakis: Logic and Disorder," Musical Times, vol. 116, no. 1586 (April, 1975), p. 329.

- Christopher Butchers, "The Random Arts: Xenakis, Mathematics and Music," Tempo, vol. 85 (Summer, 1968), p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 2.

- Matossian, Xenakis, p. 98.

ED NOTE: Also see DJ Spooky's tribute to Xenakis