UNIQUE RECORDING SPACES

Into a Cistern- Discovering an Echo

The Constraints, Liberties and Effect of Place on Recorded Music

by Domenic Maltempi

(June 2013)

This essay will touch on the power of place as it relates to recorded music. I present no loose little mistress-list that rattles itself off in splendid flesh-bone-suck order. This is a nebulous topic in some ways, a bit slippery for sure, and it's just one of many points of entry as to how a recording is more than the sum of its parts, much like understanding language would require much more than a mastery of its grammar.

Producers and engineers, ancient or cutting edge music consoles, depressed boyfriend pressures on migraine-proof drummers, LSD in the tangerine punch gags during a critical mixing session on speakers that make things sound different than what you're accustomed to at home ---all of aforementioned was a mere sampling of investigative points of entry, on how recorded music ends up sounding the way it does. I aim to muse around, have some fun wondering how the place(s) of a recording does change the way we hear music when we are made aware of it, and how it effects (if it does) the recording itself.

It would be excellent to have some double blind test results dealing, or a case study where people (screened I guess for this & that) in a room with headphones, turntables and a little scantron test, maybe one of those little blue essay books if people want to elaborate on answering questions. Information would be read by some listeners before hearing a certain recording. This information could be accurate, a distortion, an outright lie. It would give the listener a back story about where a recording was made (most of locations would be ‘exotic' or in any event—not a studio) and try to figure out how it changes listeners judgment or if does. The results of such a test might be a whole mess of useless horsehola, but it might be fun and revealing nonetheless.

The idea that the creative act morphs along here or there, depending on where you are, that maybe even being in a certain room with a certain someone or something can make the difference in elevating a part of the sound, is extraordinary. The same would hold true for how a place inserts itself in the fabric of the creative act. I know there is something ‘bunkum-flirting' or ‘kissy-fucky' about this idea in and of itself without specifics. But let's leave the technical critiques for somewhere else.

It's easy to hoax-up some malarkey about how simply avoiding recording in a regular ol' studio, with a competent and talented sound engineer, will make your record really special—as you will be ‘free' from certain routine constraints. It's hardly that far-out an assertion that place has a strong impact on things as varied as love-making, selling sherbet or wondering about the devil. One woman's sense of bunkum applied to an album recorded in a particular place is another woman's ‘well holy shit: now I get why they needed to record that album in Port Au Prince.

As of yet, I haven't heard the music inspired by movie Benji (The first one)--- recorded in a tremendous doghouse built with particular acoustics, sprayed with certain customized scents that evoke a certain pitch generally not emitted by dogs. The house was made for the howling style of several dogs of the same breed as the star of that film. I'm only mildly interested in the lore behind the sound, but perhaps for someone else it makes quite a difference. Let's explore. Come on.

A home studio in Northern California: It's 1990 and Neil Young is upright with a barefoot lodged in a bucket of manure. Thank you for staying at hotel horse shit Mr. Young's foot. ‘You're welcome Horse Shit Hotel.' This isn't a joke. This was part of Neil's plan.

Young recorded the vocals for ‘Don't Spook the Horse,' while foot bathing in this waste. Is there any doubt that the physical reactions caused by having his foot in there-- found its way into his singing delivery, the posture and stench-vertigo walk of the vocal in this single? Could he have brought the horse shit bucket into a studio tucked off in some seedy business park closer to L.A., as opposed to this barn near a Northern California wood? Sure, but the context of place would have been broken, the charged wand of the total package's magical and very physical power snapped. Is this just magical backstory backwash creating an aura to brush onto another recording that might not of stood out as desired by legend disseminator's, marketers, or some sincere but over-excited fan?

There have been so many technological and other changes over the last few decades liberating musicians from recording in conventional studios. Outside of recording large ensembles or getting drum tracks ‘right' or similar difficult to ‘mic' instruments, bands no longer need to record in expensive, or in some cases depersonalizing, studios, though they need not sacrifice sonic quality doing so. So you start hearing and reading more about artists that are adding another component that will enter the DNA of their songs, their albums, who they are and what they represent-- all of the places and the conditions to be found in such places.

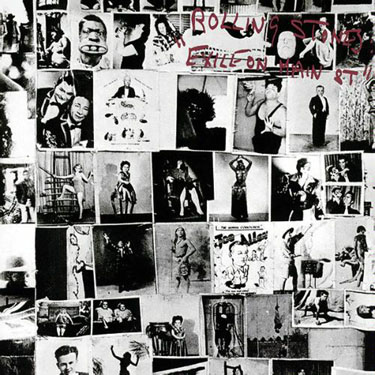

This isn't a new phenomenon. The Rolling Stones record Exile on Main Street is a fairly well known example. The Stones are one of the more legendary bands to forego the comforts and advantages of a traditional recording studio. This decision was imposed on them. Fleeing crushing new taxes levied on them in England, and having just loosed themselves from a bleeding management deal with a certain Allen Klein, who said he owned their publishing rights, the glorious year of1971 saw them begin recording in a suffocating byzantine set of rooms in Keith Richard's basement situated down in south of France. Though certainly not the only place they recorded or refined this record, we keenly want to remember Keith's basement, the odd hours, the many revelers, family members, out-of-towners--crashing, stopping by, cables slurping themselves out of various orifices-- the long laborious odd wild process in a chaotic setting that sealed a dark and crispy nimbus around this record.

The imprint of its location on the music was no simple romantic after-thought, a piece of myth-making battered with dupe-flour. There are elements of that, and one can wildly exaggerate upon it till the distortion is rank in ear and head, yet...

Such overboard story-peddling certainly doesn't hurt sales, and it's not to deny that someone got reeled into buying that record (particularly years later) or professing how much they think it's killer, due primarily to lapping up that quintessentially dark-romantic back story. But we ought to think about these sessions in Keith's chateaux as it was on a day to day basis, usually not so glamorous. That dank, no-day-or-night soul cramping and soul vomiting set of basement chambers in a home-but-not-home which allowed and necessitated loose routines and playing, and allowed and curved the spine of this music as much as the Jack being swigged, and Marseille Smack being snorted or shot-up. Songs took a crazy long time to be recorded, work themselves out. Another place, particularly a studio, would not have allowed all the fucking around, wild waiting, and so the place enters the gametes of these tunes--a bit of Stones in a French Basement---in Exile.

A place inflecting itself in music is not new. Technology and the economics of the music industry have allowed for better sonic results in even the most forbidding locales and testing conditions, places a hell of a lot more audacious or unusual than some castle in England, or Prince's masseuse's bathroom. If we don't need a five piece string section for a few songs on our album or something even more involved, we can bring our tiny mobile studios and dyspeptic or overly cheerful engineers with us to some remote town we grew up in, in a place that resonates with us in a way we want to feel while getting our songs down.

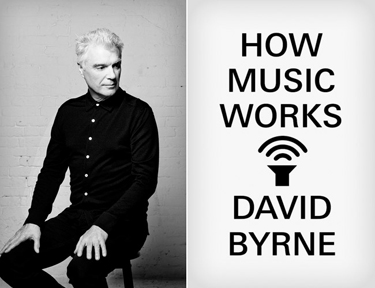

David Byrnes recent book How Music Works takes on topics as diverse as nurturing amateur musicians, to the way people experienced music, historically, or personally, due to the technology available, or the rooms and places one could hear certain acts and the competing sonic elements that went with these places. The time-line of the recordings coincide with stark changes in recording technology, economics of the music industry, and creative shifts, making some of his personal stories as it relates to recording albums interesting vis-à-vis this topic. In a section of Chapter 5, ‘In the Recording Studio,' Byrne writes how the sonic character of the recording studio space was sucked out, ‘because it wasn't considered to be part of the music.'

Byrne goes on: “Dead, characterless sound was held up as the ideal, and still is (my italics). In this philosophy, the naturally occurring echo and reverb that normally added a little warmth to performances would be removed and then added back in when the recorded was being mixed.” This passage made me think about adding preservatives to a perfectly fine substance/body of sound---to artificially prolong its shelf life---to make up for something that didn't need to be taken away which gave it gusto and then calling it more refined.

During this period of music (late ‘70's, early ‘80's and beyond as I remember this sort of thing while recording in my own band in ‘90's), recording room performances of the whole band practically disappeared. Isolation of musicians from each other during the process ruled the day. Any visceral interaction during recording between players thinned out. The sound of recorded music had undergone surgery. We were far away from the days (of at that point) 60-80 years before, when if one wanted to hear music and you made it your damn self, or you heard a bunch of players performing live, and maybe they could be heard over the racket of a saloon or festival grounds, or maybe they had to fight wild noise with proper counter-tactics-- shout and holler, stamp and scream--and get your attention anyway they could before the days of amplification.

Some of the recordings Byrne made with Talking Heads in these studios seemed diluted, and so far away from what a band sounded like on stage, or what their sound ‘really was like.' Some of these professional engineers in their state of the art palaces couldn't make these bands sound come alive as who they were or who they could be. He concludes that it was no mystery why fans, recording engineers and players would be susceptible to thinking that when they did succeed, it might have been due to some mystical quality, that skill wasn't enough. How else to explain the epochal recordings made in a Sun or Motown Studio, than invoking some ‘ineffable essence that made the records birthed in those places so good.”

It's easy to invoke similar slinky or not so slinky reasoning and ‘magical thinking' as to why certain recordings made in unusual locations might also be brought to a higher level due to the place they were recorded. In these cases, one can't point to the aura thickening around certain studios that churn out so many awe inspiring records that the aureate beard of old Midas shags around its very dry walls, furs its plumbing, and inhales its smoke filled listening rooms with laughing aplomb. Something else is at work, is afoot.

There are so many albums recorded in unusual locations these days. Its 2013, these stories are only going to proliferate. Which of these albums were truly affected by locations in a substantive way? Surely there are more gimmicky albums looking to shake and boost its mystery moneymaker, enshroud its ordinariness in a plumping array of enigmatic vestments than not. The ‘where' of an albums recording can be greatly exaggerated, and reduce more obvious conditions/reasons for an album sounding the way it does such as copious amounts of drugs taken, or a certain animus between band members at a certain time, or contract pressures.

Let's now go over a few stories related to albums where unusual or non-conventional places and conditions of these places might have changed the way they sounded relative to them being recorded somewhere else.

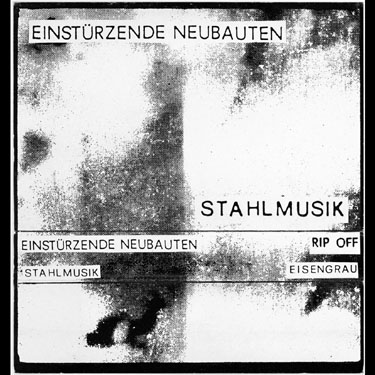

Einsturzende Neubaten's early and rare album Stahlmusik was recorded in a pillar keeping the Stadtautobahn Bridge in Berlin from crashing down! The band's record company has it that “the inner core of the pillar could only be accessed through a crawl space, and candles were lit to monitor oxygen levels.” Candles monitoring oxygen, pillars, autobahns! Oh Fuck! It's hard to believe that the intensity of being in such a place didn't rewire the brain and body of the tall lead singer/guitarist Blixa Bargeld, bent over in this stony dark place with little amp and wizened guitar howling in ways endemic to where he was, while drummer N.U. Unruh went to town smashing away on oil drums with stout bricks, pummeling the walls of the autobahn like a madman. If place strongly activates our behavior in a complex of other competing and coordinating forces, bringing out more of something than something else, looking for an advantage; then how can we imagine this album recorded somewhere else with the same force? Never mind the way we think about it while listening, imaging good old Blixa becoming ‘one' with the Autobahn or something.

The efforts made to make these harsh conditions live into the sound and absorb itself into the fledging essence of this after-the-world industrial sound that ‘EN' was developing--and became critically acclaimed for--are impressive. Even if one's not familiar with the band, or doesn't care for this sort of music, it's obvious that dealing with these interesting impositions of place highly impacted the way this record sounded. Can you really make a Stahlmusik that's NOT underneath the Autobahn, but instead in some studio? Perhaps you could gauntly imitate the capillary chewing power of it with adding this or that to the mix, or running some software or something, and maybe that's good enough. But backstory posturing and mere natural effect of place (acoustics et cetera) as the only differences one could legitimately site would seem way off the mark.

For every story like the one related above, there are many that smack of cheap myth based on a skinny neck of predictable stories. When you read something put out there by a promoter that starts “this album is more traditional, and you can tell because we recorded it in a room where Willie Dixon once sat down,” it shouldn't take long for us to pull out our little Benji-Bullshit faces, and dismiss the whole think as scammy. Maybe this sort of thing has its corollary in an admirer of Dostoyevsky visiting the Siberian prison he was sent to, passing their hands over the recycled air that Dostoyevsky possibly sniffed while mentally articulating some future portion of a masterpiece, and feeling oddly certain that they will now understand his work in a way that hitherto they were incapable of. But still...

To cite a very different type of example, Matthew Herbert has become notorious for his many well-made and thoroughly enthralling concept records. His reputation for using the most unconventional spaces to record music, with the incredibly odd and difficult conditions that come with them, is unrivaled. Is that such a wonderful thing? I don't really care much about evaluating, but contemplating the many places with its attendant conditions for recording drums on Scale is a pleasing, and thought-racing exercise: a hot air Balloon sailing over 2000 feet, his car while ripping up the road at over 100 MPH, a mining cave with the potentially perilous situation that banging on a drum might cause, hanging over the participants heads. As fascinating, or as fun, as the ideas or images conjured up by imagining these recording locales and conditions are, it's difficult for me to believe that these straining, high pressure, roiling sort of drumming location scenarios had an impact on how these songs sound, or the way I think about them knowing how they were made. I mean they do, but not in any, or salient or meaningful way. It must be some sort of conceit, or built in thing that I'm not able to self-examine so easily that makes me feel this way. Perhaps it's because the music on Scale is so smoothly electronic, complicated and warm at times, but mostly a sort of fleshless, tightly programmed thing, that I want to reject the idea of that element (drums played in x or y or z band, et cetera) of this recording having the effect that let's say Neil Young's foot in the horse shit while hanging at some Golden State Farm did.

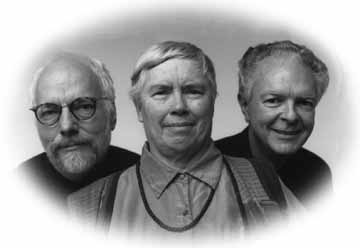

When Pauline Oliveros discovered an echo that would live for 54 seconds, she contacted Foster Reed, founder of Albion record, a man who has recorded Morton Feldman, John Cage, and many others. He would help her and trombonist Stuart Dempster with what would become their album Deep Listening. Some of Reed's records have taken 10 years to make. Damn sure many of those didn't all happen on some chair, in some building, some takeout menus scattered on a spongy red couch, divorced from the world long ago. The sustained tones offered by didgerdo, T-bone, voice, garden hose, but predominantly Pauline's accordion, are modulated with delicate turns, a master seamstress nimbly assembling an Olympian vestment for sounds that are glazed with a beautiful preternatural dry shine. Oliveros and Dempster ventured into a rotund cistern on the Olympic Peninsula at Fort Worden in Washington State. This rotundity spun that old-age of an echo close to a minute mark. One can imagine the 2 million gallons of water that once nested there.

For Oliveros, deep listening is as much a philosophy as the name of this particularly beautiful album dating from late ‘80's. Here, the power of place to make little instrumentation come across as a full-on orchestral group, devoid of any electronic processing, is truly in your face. You are shortly lurking in the cisterns of yourself while hearing it. What would we expect from a woman who has taught many a class, and many a person in various settings, that a dripping faucet, properly heard, is as profound as the Brandenburg Concertos?

Albums can be closely related to space. Sometimes that space is its mother, sometimes its missing cousin, other times a guardian angel that takes too many smoke breaks, looking for a breakthrough moment.

Phil Elverum of Mount Eerie recorded his albums Clear Moon and Ocean Roar in a studio that he built in an abandoned Catholic Church administrative building. Elverum describes in interviews how he simply began experimenting, no intent to make an album, or develop some wisp of an idea. He had been playing on the road all the time for over a decade.

This building, and the town it lived in, was a chance for a respite from all that. It allowed for experimenting, where time passes deeply, slowly, allows place, particularly that selected, and then built into by the artist, to become integrated into sound. What will work in the room? The artist doesn't need to rely on manufacturing a mythos- he's creating in the place that is the beginning and end of creating, not a place to bring a few tunes, and have them finished off, polished, perfected, realize.(not that polishing a record with studio techniques is automatically bad by the way.) Song and place begin to mimic each other's voice. Just two kids testing new sounds they've created, sitting back to back, often without a word, realizing what's going on without some bloated investigation or need for grand discovery- a simple and powerful relationship fostering each other's development.

There are several reasons why we become captivated by place as it contributes to recorded music. Sometimes we're Velcro –jacked in with a story about a hooker-ghost in a rented castle after we already love the daylight and the dark, off of some treasured album. A comic or strange set of streaks color our interest, and might intrigue some to try to ‘find the place in the sound.' Other times, we trick ourselves into thinking a song or album that never really pushed us anywhere, nor had some pleasurable numbing effect, is more interesting because of an exotic location. It's not impossible that someone pointing out a set of conditions in place where recording(s) happened, persuaded us to listen yet closer, and we find ourselves at a greater point of appreciation.

From unearthly solitude, to the many attempts to capture curiously resonant acoustics, artists will continue to search for some extra or added quality. They will pursue places that they suppose will separate them and their sound from the perceived limitations of a conventional recording studio.

I'm interested to hear of albums that people have made or heard that they feel the place made a meaningful impact to the end result of recording. Feel free to write in.