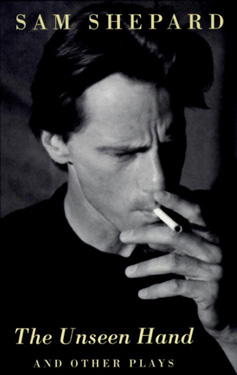

SAM SHEPARD

Tribute by Peter Stampfel, Part 3

(February 2018)

Most of the following information was from a long talk I had with Paul Conly:

Back in late 1966, Paul Conly from Lothar and the Hand People, came over to our place, where we were jamming with Sam. You've got to see Lothar, we told him. Lothar and the Hand People were the first band Antonia and I were positive were going be a huge success, but wasn't. We were wrong. One reason was a crooked manager (just sign this contract, our attorney says it's fine), which many musicians had, since they weren't good business people. But the other was something unprecedented: for the first time ever, the music scene hit a critical mass: there wasn't enough room at the top for all the great bands.

In their hometown of Denver, Lothar et al, deliberated between going to New York or San Francisco. Ironically, I'm sure with the smaller West Coast scene they would have made it there. They were somewhat like the Lovin' Spoonful, only influenced by R&B instead of folk.

Sam went to see them, and was knocked out. At around this time, Newsweek did a three page spread on Sam and the off-off-Broadway downtown scene, and when they asked him about theatrical highlights, he said the rock scene was much more interesting than the theater scene, citing the Mothers Of Invention and Lothar and the Hand People.

In 1970, Sam asked Paul Conly and Rusty Ford (real name), Lothar's bassman, to play some songs with him in the lobby between two of Sam's one-act plays, Forensic And The Navigators and The Unseen Hand. Forensic had originally opened three years earlier in 1967 with O-Lan Johnson playing the part of the girlfriend. In the 1970 version, she was the pregnant girlfriend, being indeed, pregnant with Sam's first child.

Paul played a prototype ARP synthesizer in The Unseen Hand. ARP had lent him the instrument as a promotional gambit, and was probably the first synthesizer used in a play. He improvised a different part each performance, accompanying a prepared tape that he had made for the play. Paul had written some songs inspired by the play for possible incorporation, but Sam thought they would interfere with the continuity. Instead, Sam, Paul, and Rusty played some of them between shows, along with others that Sam had written. Sam didn't tell me that he had written that many songs. I had only heard "Take A Message To Omie." I would really love to hear his other songs from the period. I just asked his son Walker whether there is any sonic or sheet music record of any of them. "Good question, I don't know," he said.

The sets for the plays were done by Santo Loquasto, who went on to be the set designer for 61 Broadway productions, and several Woody Allen movies. I was not familiar with him, so I Googled his name. Oddly it says his career started with the set for the Broadway production of "Sticks and Bones" in 1972, two years after his set designs for Sam, which Google seemed to not be aware of.

These plays were attended by Dick Clark of American Bandstand, who sat in the front row for the first play, Forensic and the Navigators. The play ended with a dense fog produced by dry ice, which enveloped the audience. Clark had been sitting in the first row. Outraged, he stomped out, ignoring Paul, who wanted to shake his hand.

Robert Redford and his wife at the time, Lola Van Wagenen, attended the plays as well, and Redford was so impressed with The Unseen Hand, he asked Sam to write a movie script for it, advancing him $10,000--a lot of money back then--which Sam used to buy a small home in Nova Scotia, where he spent several months trying to write s movie version of The Unseen Hand. I didn't know how Sam financed his new home, just that he had bought a place up there, where he spent several months.

Sam knew I collected bottle caps: one of his plays even featured pirate treasure, which turned out to be a bottle cap collection. He sent me a bunch of great local bottle caps from up there, which I still have. Sam worked like hell on the screenplay. Sam has always worked like hell, but he was not satisfied with the results. Redford said that's all right, keep the money. A real mensch.

Jeffrey Tambor, who went on the play Hank Kingsley on the Larry Sanders Show and Maura Pfefferman in Transparent, was the only person to compliment the music Sam, Paul, and Rusty played during the whole run.

Everyone followed the old theater tradition of partying all night long while waiting for the first reviews to come with the morning papers. Sam got pretty drunk and said bitter things about critics, many of whom had not been treating him very kindly.

Sam also used Robin Remaily of the Holy Modal Rounders to write a song, "Silly Boys," in the style of Marlene Diertrich/Kurt Wiell, for his play, Back Bog Beast Bait, which Robin totally nailed.

Once more, fate came along, doing one of her stranger dances. Later in 1970, Sam said he wanted to do a new song he had just written called "Blind Rage." Fate sent Patti Smith, a journalist at the time, to write a review of our band's performance. Patti asked if I could talk to her after the show. I said, sure.

Sam performed what was to my knowledge the only performance of his song, "Blind Rage," ever, singing at the top of his lungs while he pounded the shit out of his drums, a big vein throbbing away on his forehead. The only words I can remember were:

I'm gonna get my gun and shoot him and run,

Blind rage!

Pounds the shit out of his drums

Blind rage!

Pounds etc.

Blind rage!

Etc. etc.

After the set, instead of talking to me as she had asked to do, Patti made a beeline for Sam. I didn't listen to their conversation, but it was obviously intense. Shortly afterwards, they went to Patti's room at the Chelsea. I'm not sure how long it was before he saw his wife, O-lan, and their less-than-year-old child, Jesse Mojo, again. Antonia and I had tried to convince Sam and O-Lan to name the baby Mojo. Thank God they made it his middle name instead. For decades, Sam never let me forget that.

Years later, an English music writer interviewed me about Patti and Sam's first meeting. I said, regarding Sam: he "copped her entire mind". It never occurred to me that what I said was a bit of archival American slang a Brit might not understand. In the ‘60's, it meant to make a most powerful impression. When I saw the interview in his book, he said. "Cocked her entire mind." Oops.

But he sure did. And so did she. Cop his entire mind.

Sam invited me to the Chelsea to officially meet Patti, the few sentences Patti and I had shared before the gig didn't really count. Sam had told Patti I was seriously into World War Two airplanes. So Patti had a present for me. It was a meticulously illustrated book about Sentai (squadron equivalent) markings of Japanese Army aircraft. The markings were really cool, much more interesting than their American equivalents. She explained that she got it because she wanted to do a drawing of an American plane shooting down a Japanese plane, and she wanted to make sure the Japanese one had accurate markings which is one of the coolest things I've ever heard a woman say. Here, she said, it's yours. One of the best gifts I ever got. Thus copping my entire mind. I still have the book.

They had written a two-person play about their approximate selves called Cowboy Mouth. The play took place in Patti's room at the Chelsea Hotel. There was actually a third person in the play, a guy dressed in a lobster costume who would deliver lobster whenever they ordered it. Sam wore a Gabby Hayes style busted-up sort-of-cowboy hat, with the front brim turned up. As a kid in California, Sam had been fascinated by Gabby Hayes, who was arch-sidekick to several Western stars, from Hopalong Cassidy to John Wayne to Randolph Scott, and most famously, to Roy Rogers, "King of the Cowboys."

I found the play riveting, one of my all-time favorites. It was supposed to have several performances, but for some reason or reasons, I never knew, Sam fled the city without a word to anyone after opening night, joining the Rounders while we did a gig in Franconia College in Hew Hampshire.

Some college girls up there thought Sam was some kind of aging delinquent in his leather jacket, and were being loudly insulting right in front of him. Sam and I just smiled at each other.

Sam, O-Lan, and Jesse stopped by to visit Antonia and me in New York later in the 70's. I had made a plastic model of a Japanese fighter plane called the Hayate, which I gave to Jesse. I don't remember much else about the visit.

But we stayed in touch. He and his family moved to northern California. In 1978, my wife-to-be-in-four-years Betsy Wollheim and I visited Sam, O-Lan, and Jesse, who was now eight years old. His address at the time was 33 Evergreen Street. Which was odd since ours was 33 Greene Street.

Sam let the grass grow in his back yard so it would attract rats, which he liked to blast away at with a shotgun. He had set up his basement with a narrow central corridor and small rooms with doors marked to resemble apartments on the Lower East Side which he laughingly showed us: "Look--I built my basement to look like the East Village!" He had been playing saxophone, and we jammed away on my gonzo version of "Handy Man," which he said was much better than James Taylor's. It a hell of a lot more speed-inspired for sure. Sam seemed happy and was full of energy.

We took our nerdy friends Roger and Janet to meet Sam, and they went into total geek mode, going on and on asking him endless questions, and he answered every one with warm, patient kindliness, bless his heart.

He took us somewhere in his car, and he told Betsy, "Don't worry, I'm an excellent driver," and then tore off like a bat out of hell...excellently. Years later in Minnesota, his daughter Hannah told me he used to pick her up from high school in his Corvette, and take off laying a strip of rubber.

This was 1978, and we saw the opening of his Pulitzer-prize winning play, The Buried Child, which is my all-time favorite along with Cowboy Mouth.