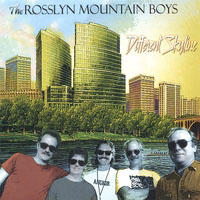

Rosslyn Mountain Boys

Rossyln Mountain Boys at Columbia Station, 1978

Joe Triplett Could Win Back His Audience

... If We'd Let Him

By Rich McManus

(August 2009)

When Joe Triplett mock-staggered off the stage following an encore version of "Shake, Rattle and Roll" this past Jan. 3 at Falls Church, Virginia's State Theater, he had not only shaken, rattled and rolled a delighted audience, but also decimated any perception that the 63-year-old singer had lost any of his ability to incite riot in the hearts of those who loved the band he fronted in the 1970's, the Rosslyn Mountain Boys. The last thing you would have imagined is that Triplett, a Flat Natural Born Good Timin' Man if there ever was one, has not appeared regularly on stage since the early eighties.

The State gig was another of the periodic reunion concerts put on by the RMB, who shared the bill that night with Washington's perdurable Nighthawks and the Charlottesville All-Stars. All three bands crowded the stage for the encore, but it wasn't until Triplett--summoned from a quick rendezvous with his girlfriend in the balcony by Nighthawks harmonica player Mark Wenner--wound his way, drink in hand, back to the stage that things took off. Triplett's unhinged embodiment of staggeringly good times pushed the show from the status of rewarding blues warrior reunion to Honky Tonk Heaven.

A month later, looking back at the show, Triplett admitted he had fun, but wanted to talk more about how much he had enjoyed the Nighthawks, who have been a Washington institution for close to 40 years. "They're playing better than ever. I don't think I've ever enjoyed them more."

Triplett is, by all accounts, exceedingly modest, which goes some distance to explain why today, only dedicated fans still remember the Rosslyn Mountain Boys. These folks tend to agree that the band should have been known and loved from California to the New York islands, rather than from Gaithersburg, Maryland, to Alexandria, Virginia.

Both a singer and songwriter, Triplett was legendary in 1970's D.C. for a charisma that could bring audiences to tears one moment and leave them giggling the next. He was going to be the next George Jones, the next Roy Orbison. His country-rock band was going to out-soar the Eagles and the Byrds and finally establish Washington as the peer of England or California as a font of Top 40 hits. But it didn't happen.

Yet.

Joe, now a gentleman farmer—"I do everything a farmer does, except actually farm"—is busy these days building a house on property that has been in his family since the early 19th century, near Front Royal, Virginia, at the head of the Shenandoah Valley. No longer formally in the music business, he remains the helpless vessel of an admittedly intermittent muse. Though he concedes that his voice has lost some of its power and stamina, he still brings an alluring uncertainty to the stage, which is what kept the audience hanging around at the State Theater on the Saturday after New Year's.

Triplett, it turns out, is as much actor as singer, which is a tremendous asset given that his strongest material-- hard-core honky-tonk from the '50's and '60's--is essentially 3-minute moral dramas. Audiences can't turn away from his antics on stage because it seems almost beyond him to direct where his muse will lead.

Although he still sings every day—"I've always got something in my head"—it's mostly to the horses and to the hills. But he should be back in front of audiences because, much like America, he is wild with potential, flirted with by the angels. He's also unpredictable enough to leave audiences anxious to find out what he will choose and where he will lead them.

Of course there's no such thing as the Rosslyn Mountains. The name poked fun at the ridiculous City-in-a-Box that Rosslyn, Virginia, just across the Potomac River from D.C., was becoming in the 1970's. Two young guys—Happy Acosta and Joe Triplett--were getting ready to perform as a freshly minted duo in front of a barroom audience. They needed a name in a hurry, so Acosta blurted it out, in tribute to the neighborhood where the two musicians shared what Triplett calls "a shack."

"I thought the name was kind of lame, but it was just for one night," said Triplett. "I mean, we weren't going to call ourselves 'Joe and Happy.'"

The year was 1973. The inaugural show was at a bar called the 21st Amendment, on Pennsylvania Ave. The two friends were already veterans of a host of bands whose names were never destined to appear on anyone's iPod playlist (ever hear of the Jackals or the Human Zeroes?). Joe had most recently spent 3 years as a member of Claude Jones, which was Warrenton, Virginia's answer to the Grateful Dead—a hippie band whose members all lived together at a rural outpost they called The Amoeba Farm. Acosta had been a guitarist in the band. A picture of the group, sprawled across a rustic hillside, had run in the Style section of the Washington Post. "We were the darlings of the Washington rock scene in 1970," notes Triplett wistfully.

Though a virtual unknown, Triplett had, even at this obscure junction of his life, already accomplished something the best bands in the world had not: he had knocked the Beatles out of the number 1 slot on Washington AM radio.

In 1966, while home on summer vacation from studies at Kentucky's Transylvania University, Triplett had been the lead singer in a band called The Reekers. The band, a bunch of suburban Maryland kids, had a hit on its hands called "What A Girl Can't Do."

"It was a concerted effort to sound like the Beatles," he remembers. But bandleader and guitarist Tom Guernsey felt stardom would be hampered by such a noxious name, so the musicians came up with something that sounded more radio-ready--The Hangmen.

Their high-energy hit, which featured Triplett growling "I don't wanna have to tell you what a girl can't do," bumped the Beatles' "We Can Work It Out" from the top of the charts, at least for a few weeks, Guernsey recalls in an online interview.

No one growing up in D.C. in the 1960s heard that song and said, "That's Joe Triplett." It was a Tom Guernsey and the Hangmen song. Yet in each of its 2 minutes, 27 seconds, the tune delivered exactly what Triplett has always delivered, and still delivers to this day—raw assurance that the singer believes his song.

The stage is a place of strange mathematics. Many performers are lesser than it, some are equal to it, and a few are enlarged by it, discovering a natural home and an identity. Joe Triplett belongs in the latter category. Though life has occasionally diverted him into lesser callings—he has been at various times a motorcycle mechanic, a carpenter's helper, "a LAY-bor-er," proprietor of a tire-recapping business, auto mechanic and owner, for a decade, of Key Motor Co. Inc., a used car business in Frederick, Maryland—his real home, his native dimension, is in front of his band.

"I had all sorts of get-rich-quick schemes," he laughs. "Anything to support my budding musical career, what I perceived to be my destiny as a huge star, sitting by the kidney-shaped pool in Hollywood."

Perhaps T-Bone Burnett and Rick Rubin, the legendary producers who prompted late-career miracles for Led Zeppelin's Robert Plant and Johnny Cash, respectively, should take note: when Triplett takes the stage, be it 1975 or 2009, an emotional force is unleashed, not cheaply, but by degree. He plays it perfectly straight for the first tune or two, but look at his posture. He's starting to address the mike as if it were a new acquaintance, a skeptical stranger. He's kind of cocked toward it—this relationship could become adversarial.

Then notice how his facial expression subverts the earnestness of a country lyric. In a dozen subtle ways, he's enlivening your standard cheating song, embodying not only the inevitable parties at conflict, but also the detached—more often than not bemused--observer. He's like a surgeon so skilled that the object of his dissection—the American popular song, Nashville division--remains not just uninjured but rejuvenated.

Triplett sings as if his own heart, his own sanity, his own ability to take another minute of this, is at stake. You can't be that convincing and have an inauthentic relationship with large truths. Paradoxically, he can leave each member of a crowd with an intimate sense that he's been talking only to them. He is the kind of singer who sends audiences out into the night asking, "Who knew that Conway Twitty, and Ernest Tubb, and Porter Wagoner were such geniuses?"

"He's a great storyteller," observes Lin Arroyo, who together with RMB keyboard player/guitarist Peter Bonta ran a recording studio for years, post-Mountain Boys, in Fredericksburg, Virginia, called Wally Cleaver's. "His phrasing could be compared to Sinatra's."

Triplett almost doesn't need words to tell a story, however. You could probably get the gist of his songs simply by watching his pleading face, his hunkered stance, the way he exaggerates his guitar strumming to the point of near-comic emphasis. The rigidity in his limbs is meant to imply purpose, discipline, staunch support of his bandmates. His repertoire, it is clear, possesses him. To audiences, it is beguiling. How can 3 or 4 minutes of music contain such consequence? How did this suburban kid become a singer as definitively American as a map of Virginia?

To the thousands of youngsters who grew up in metropolitan Washington in the years just after World War II, music came down from the same source as the inspiration to make music in the first place--the heavens.

"What I was influenced by is what was on pop radio around Washington, D.C., in the early 50's, before rock and roll," recalls Triplett, who grew up the youngest of three sons of an auto parts salesman and a housewife. "I was listening to pop music from the time I was 5 years old. I bought Frank Sinatra records in, you know, 1950. But when rock and roll hit in 1954 with Bill Haley, I flipped for rock and roll, of course... I probably listened to Ray Charles more than anybody."

The first person to acknowledge that Triplett could sing was a local TV host. The year was 1957 and Triplett was 12, just starting to play trumpet at Bethesda's Western Jr. High (now Westland Middle School). He and his classmates' rock-and-roll band, the Flat Tops, appeared on the Milt Grant Show.

"We did 'Peter Gunn,' the Henry Mancini tune," Triplett remembers. "I blew Peter Gunn on trumpet and then we did 'Ready Teddy,' and maybe another Little Richard tune. After the show--it was like a big sock hop thing--somebody came up and said 'Hey Joe, Milt wants to talk to you.' We went back to his office. He didn't want to talk to the other guys in the band. He said, 'Son you've really got something there, you know.' He tried to get me to join his band—something like 'Milt Grant's Midnighters.' I said thanks, but I'm loyal to the Flat Tops. I couldn't leave my buddies in the lurch."

Even as a greenhorn rocker, Triplett had attitude. He recoiled instinctively from an outsider's corralling urge.

Half a world away, Peter Bonta was undergoing the same sort of rock and roll initiation. Six years younger than Triplett, he was in Bangkok, the son of a career Army officer. Under the spell of AM radio, he became enchanted with the same roster of American singers that had infatuated Triplett. When Bonta's family moved back to the States and settled in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1960, Peter became even more fully indoctrinated.

"It was pretty much rock and roll from then on," he recalls. "Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis and, of course, the Beatles. The Beatles ruined my life."

His parents started him on classical piano lessons, but Bonta soon bridled at the formality of European music. He also rankled his teacher by wanting to learn popular songs, which required him to stray into the forbidden territory of improvisation.

During high school, Bonta, by now a self-taught electric guitar player as well as a keyboard player, found like-minded kids and formed a group called the Ice Cream Grenade. Bonta had his own Milt Grant experience when the Ice Cream Grenade, featuring Peter on organ, beat 200 other groups in an ongoing televised Battle of the Bands on local station WDCA-TV's afternoon variety show Wing Ding.

Once, when one of the "beer-hall bands" with whom he occasionally sat in lacked funds to pay him, Bonta was given instead "an old Vox tear-drop electric guitar. That was it, the beginning of the end."

Triplett had made his debut as a songwriter during 11th grade at Bethesda's Walter Johnson High School, when he wrote "259," a song about his Studebaker. He admits it borrowed heavily from the Beach Boys' "409," another paean to hot rod musculature. Interestingly, Tom Guernsey later reworked the tune and called it "Streakin' USA," to take advantage of the old campus fad of naked dashes, says Triplett. "It almost became a giant hit," he recalls. But just before it could be released, Ray Stevens' "The Streak" eclipsed it as a novelty tune.

By the time the 1970's began, the musicians who would become the Rosslyn Mountain Boys were well launched in apprenticeship bands. Bonta, who had briefly attended Georgetown University, became a member of the Nighthawks. Triplett veered from the jams of Deaddom in Claude Jones toward the country sound of the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers and the Carter Family.

"I always wanted to play country music, and became a convert to hard-core country—Merle Haggard, Hank Williams, George Jones," Triplett said. "I thought, God, that's what I want to do. That's what I really love."

Prior to the RMB's debut, the original two Mountain Boys, Triplett and Acosta, "sat around for months listening to Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, the Osborne Brothers, Jimmie Rodgers," Triplett recalls. "Hap turned me on to a lot of stuff I'd never heard of." The duo soon added drummer Bob Berberich, a fellow Washingtonian who had played with Grin, guitarist Nils Lofgren's (now of Bruce Springsteen's E St. Band) breakout band.

In June 1974, classic-era RMB blossomed when Bonta was lured away from the Nighthawks by Triplett and Acosta. "Happy and Joe came to see me playing with the Nighthawks at the [Washington nightclub] Reading Gaol, since the 'Hawks were really garnering a hot local rep," Bonta remembers. "They asked me to join and I was actually the band's first bass player because they couldn't afford to have me and a bass player. They asked if I played bass and I lied and said, 'Sure!' I bought a bass and played it for a few weeks until we had enough gigs to ask Claude Jones' bassist, Jay Sprague, to join.

"I was a huge fan of Joe's since the Hangmen and Claude Jones," Bonta recalls. "I couldn't believe the great Joe Triplett wanted me to join the band."

"Our first break came when we became the house band at the Shamrock Tavern in Georgetown," drummer Berberich recalls. Soon after, the RMB earned a weekly engagement Wednesday nights at the now-venerable Birchmere nightclub, then located in a storefront off of I-395 in Virginia near Shirlington. Audiences grew by word of mouth—"Triplett had people in the audience crying last night"—and clubs were packed whenever they played.

"We had lines around the block to get in the Birchmere, [and other Washington clubs including] Desperado's and the Cellar Door," said Berberich. Adds Triplett, "We were drawin' pretty good back then. I remember seeing lines snaking out the door and thinking, 'Wow, they're lined up around the block to see us.'"

"If there's one thing that consistently sets the Rosslyn Mountain Boys apart from the pack of local bands who ply their trade nightly in the D.C. and suburban bars, it is the emotional credibility of their music," wrote Joe Sasfy, a music critic for Washington's alternative weekly The Unicorn Times. Sasfy, now a consultant to Time-Life's music division, published perhaps the definitive review of the band in 1977. "With a stage presence and vocal style that are the most captivating of any performer in the D.C. area, Triplett acts out a nightly drama of cheatin' women, perplexed lovers, juiced rednecks, tired truckers and stifled lust," Sasfy continued. "Triplett is able to stand in the center of each song and claim it as his own."

"That was the high-water mark of the band," recalls Bonta. Their first self-titled record had come out on Adelphi Records (then home to T-Bone Burnett also) in 1976 and was selling well regionally. He and Triplett fondly recall a weekend bill at the Stardust Inn in rural Waldorf, Maryland, where the RMB opened for Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn.

"Conway was totally impressed that Joe sang 'I Didn't Lose Her, I Threw Her Away,'" said Bonta. "Conway was dumbstruck. He said, 'I never do that live because I can't hit the notes.'" Triplett remembers the frenzy that Twitty generated among the women—many of them in bee-hive hairdos--who had come to the show. "I thought the place was gonna melt."

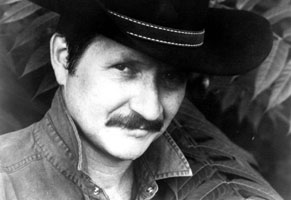

Joe Triplett

The RMB's dream of stardom was rapidly coming true. "We were thinking record contracts, tour buses, swimming pools, limousines, gold records... [to hang] on the wall of our lean-to," quipped Bonta. "We had great expectations," Triplett agrees.

In addition to regular gigs at Desperado's in Georgetown and the County Line in Arlington, Virginia, the RMB also played the Psyche Delly in Bethesda, Mr. Henry's-Tenley Circle, the Childe Harold near Dupont Circle and the mid-Atlantic college circuit, ranging from Blacksburg and Charlottesville, Virginia, north to State College, Pa.

Triplett, aware enough of his own divahood by then to refer to himself occasionally as Ego Triplett, would often pull up to shows in his old Studebaker. "We called Joe 'The Human Tardy Slip' in those days," says Bonta. "We'd all be onstage ready to play, and here would come Joe, carrying his amp in one hand and guitar in the other."

Though he wielded a guitar onstage, often a fire-engine red Fender Stratocaster, Triplett, who didn't learn guitar until he was 23, and then only to accompany his singing, says his playing was unneeded. "I was surrounded by absolute monsters," he says. And it's true. Pedal steel player Tommy Hannum was an ace picker, so fine a musician that the day the RMB folded, he went straight to Nashville, where he has earned a comfortable living ever since. Sasfy wrote of his prowess, "he can tease drops of honey or splinters of lightning out of his pedal steel on a moment's notice."

Both Hannum and Triplett could write as well as play and sing, and the band performed a mixture of cover tunes and originals every night. Regardless of the material, once Triplett became emotionally engaged, the stage belonged to him. His version of Roy Orbison's "Oh, Pretty Woman" provided desperate drama. It was easy for women in the audience to imagine themselves the object of the longing he coaxed from the song. Club owner Rich Vendig, who ran Desperado's, says the RMB consistently drew well, "mostly an urban, white, female crowd. Lots of regulars." Men found in Joe a natural leader; once he raised his hands over his head to clap out the beat to Gary U.S. Bonds' party anthem "New Orleans," listeners helplessly followed suit, foregoing fears of looking goofy for the imperatives of getting down with this impish emissary from the Promised Land.

Perhaps one of the band's weaknesses was an elemental democracy that saw lead singing duties passed from musician to musician, even if the talent level varied. "It was too much of a democracy," says Vendig. "Joe had the voice and the songs and could have been a star. Tommy had stage presence and was the best looking. But everyone wanted to do too much and not defer or sublimate themselves." Bonta says one reason everyone in the band sang is because 4-5 sets a night in smoky bars was too much to ask of a single vocalist.

Not a show went by when drummer Berberich wasn't called upon, often with mock ado by Triplett, to do Gary Stewart's "Flat Natural Born Good-Timin' Man." Hannum too would get his share of vocals, even though his range did not approach Triplett's. Bassist Mike "Rico" Petruccelli, whose musical training was perhaps the band's most formidable—he had been playing bass professionally since age 15, in 1968, and had two music degrees from the University of Maryland--also got tunes. "It was an empathy kind of thing to share vocals," says Petruccelli. "That's just the way the five of us were."

As good as the mid-1970's were to the band, it reached a point of stagnancy as the decade wore to a close. Their second album, Lone Outsider, on the Schizophonic label, had sold poorly, and when their manager took it to Los Angeles to try and attract major label attention, a studio exec's hallway conversation, overhead by manager Michael Oberman, might as well have been the band's death knell: "Anything with pedal steel [guitar] is out—pedal steel is hopelessly passe."

"That was kind of the kiss of death," says Triplett. "Our album had pedal steel on every single cut. By 1979, I was getting frustrated. In general, the band was sort of floundering."

"We could just see we were on a treadmill," says Bonta. "We could continue playing locally, probably forever, but…"

"We should have just stayed together," Triplett interjects. "We could have been like [Washington bluegrass institution] the Seldom Scene forever. That's what should have happened. That's what we should have done. We thought we had to become giant stars, you know? We felt we needed to be national superstars or give up."

Before officially throwing in the towel in late 1979, the RMB had one final misstep up its sleeve. Early in the year, the band put all their friends aboard tour buses, changed their name to Payday and played a showcase set before an audience of record company executives in New York City.

"We put all our eggs in one basket," Triplett recalls. "All these big record company reps were there. We were okay, but we weren't true to our country roots. We worked up this rock and roll revue, which was good, by the way."

The centerpiece of the performance was what Bonta calls "a Mitch Ryder soul medley: 'Stubborn Kind of Fella' > 'Devil with a Blue Dress' > 'And I Thank You.'"

"It was good but we didn't get a deal out of it," Triplett said. "This wasn't the '50s and '60s honky-tonk country that we'd been doing before." Adds Bonta, "New York City was not ready to hear [a classic RMB set]."

Ironically, the same set that produced yawns in New York might very likely have been well-received in Nashville. "What we should have done is the country set in Nashville," Triplett ruefully notes.

Club owner Vendig concurs. "As I recall, they saved up money and had a big coming-out party in New York City. Why not Nashville? They just seemed conflicted as to identity. My view is that they failed to evoke a clear image." Vendig thinks the band could never decide if it was rock or country, and that the ambiguity eventually killed them in the marketplace.

Bassist Petruccelli confirms, "We had interest from Nashville and it was a good time to be a country-rock band, but it seemed like contractually we could never quite get it done."

"We were either ahead of our times or just behind," says Bonta.

In the aftermath of the Boys' breakup, Triplett went west to California in 1980 to woodshed and write songs.

"I had sort of a nondescript experience with nothing happening," he remembers. "Totally a futile effort, utterly futile. I sold everything. All I had was a record player, and a guitar and a Studebaker. I had my motorcycle with me. I sat there for months."

Triplett says the experience was "incredibly lonely. I would bring tunes to [producer] David Briggs [who also produced Neil Young], who was living in Topanga Canyon. I remember distinctly being crestfallen when he would say, 'Ehhh, ummm, so-so…Joe, you could probably do better than that. It's kinda mediocre.' He was right."

His sojourn in Hollywood turned leaden, Triplett came back home and in 1982, he tried to kick-start his old band the way he might kick-start one of his favorite old Triumph motorcycles. He gathered everyone but Hannum, who had been replaced with pedal steel player Barry Sless, and did a few well-received dates, but by then Bonta had been recruited to play with D.C. power pop band Artful Dodger and Sless was bound for California, where he was destined to merge successfully with Grateful Dead alumni.

Triplett's last-ditch attempt to remain a singer was a new band, Joe Triplett and the Hired Hands, but that too petered out after about a year. "It didn't really go anywhere," Triplett said. The Hands just weren't the Boys.

"I kinda gave up for a while there after Hired Hands," Triplett admits. He became a car mechanic at Wrenchmasters in Rockville, Maryland, and got a place in Frederick, Maryland, where he later opened Key Motor on Route 85, selling used cars for most of the 1980's. Every now and then he would confirm to a customer, "Yes, I'm that Joe Triplett."

One day, an old high school friend dropped by and asked, "Joe, you're great—how come you're not doing anything?"

Triplett responded, "I'm not doing anything because I need about $15,000 to make a record."

The friend had just won $50,000 in an investment contest and promptly wrote Joe a check.

"You do understand that this money's gone?" Triplett counseled. "We both know this money is history.

"He said, 'I understand.' We wrote up this little contract that said if I become larger than [country singing star] Randy Travis, he would get 10 percent or something. So I called Peter to produce it and we went in to Bias [the Virginia studio where the RMB had recorded its first album] and made a Joe Triplett solo album, which was basically just the Rosslyn Mountain Boys." The band was augmented, Bonta notes, by such special guests as rockabilly guitar master Bill Kirchen and Ricky Simpkins, who was Emmylou Harris's fiddle player.

"We took it to Nashville in 1990 and nobody wanted it," Triplett explained. "It just layed there on a shelf for, like, 15 years while I became a used car dealer, selling Volvos in Frederick."

Even though the RMB was officially defunct, the members occasionally gathered during the Christmas holidays for reunion gigs at local clubs and restaurants. After one of these well-received sessions, the band decided to release a new CD. They would use the best of Triplett's solo record and merge it with tunes Hannum was working on down in Nashville. "Tommy was literally e-mailing us his parts," said Bonta.

"Tommy had all this stuff in the can, so we merged the best of both," said Triplett. "With Peter's help, we ran [the songs] through his 'loudness maximizer tool.'" Bonta produced, remixed and remastered the songs and assembled a CD.

The digitally enhanced product, titled Different Skyline, was released on the Sosumi label in late 2005. "Putting out this CD sort of reinspired me, kind of, just to finally get product to come out," said Triplett.

The disk got no promotion, though. Its availability was tucked away on an obscure web site (http://rosslynmountainboys.com/rmb/). But its 12 tracks are vintage RMB, a tour through Triplett Territory, that uniquely American terrain where the weight of sin and shame and regret that is our Puritan past must be counterbalanced by Good Times, and plenty of them.

"I'm still writing songs," Triplett reports. "The best songs came to me in dreams—the melody. I woke up and the melody was playing in my head and I ran and I figured out what the chords were."

Though he is busy these days finishing his house in Stephens City, Virginia, tending 80 acres of pasture, maintaining some two dozen cars and motorcycles and rearing two daughters, Triplett tries to make time for his muse.

"I go in spurts playing guitar—I'm too busy as a wannabe gentleman farmer," he jokes. "I've got some songs that I would call retro-'50s, sort of juvenile delinquent garage rockabilly. I think I've got about four songs that might be good. The truth squad, really, is to tape it and then listen to it a couple of days later and decide whether it's any good or not. 'Cause I always think it's great when I'm doing it and then I can listen to it 24 hours later and say, 'nah, that doesn't quite get it.'"

Neither Triplett nor his bandmates are naïve enough to think the Boys are likely to soar again, but they are game to give it a try. Most found rewarding day jobs years ago—for example, Petruccelli has worked at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency since 1995 and Bonta is an A/V and IT specialist at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum—but the urge to perform lingers.

"That is my fantasy," muses Triplett, "one that never seems to come quite true." He says he's ready to commit full-time to the band again, but laments, "We don't have any product that's recent to show anybody. We are legends in our own minds."

"Music to last a lunchtime!" boasts Bonta.

It could be that America's current economic misery holds a silver lining for the Rosslyn Mountain Boys. Banks and other commercial concerns are now pitching themselves as solid, old-fashioned, reliable. Country music, traditionally the conscience of a nation in search of its burgeoning identity, stubbornly resists irrelevance. Assuming the struggling economy doesn't cancel the planned openings of a new Birchmere in College Park, Maryland, and a Fillmore concert hall in downtown Silver Spring, Maryland, the Boys could conceivably have regular new gigs, maybe a new home stage. Triplett could then cast off for good the alternate mantles--used car salesman, auto mechanic, gentleman farmer--and become known for what he is.