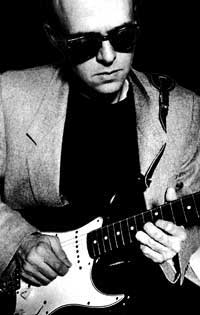

ROBERT QUINE: SUCH A LOVABLE GENIUS

Article and interview by Jim DeRogatis

Bob Quine was really weird about the phone.When I set out to write my biography of Lester Bangs, Quine was one of the subjects I was most eager to interview. I was a major fan, and by all accounts, he had been one of Lester's best friends. But tracking him down proved to be no easy task: Bob valued his privacy, and he prided himself on his inaccessibility. I finally got his number from someone who'd worked with him during the recording of Matthew Sweet's Girlfriend.

The studio insider was reluctant to give me the contact info--"If Quine finds out, he'll never talk to me again!"--and he only did it on the condition that I'd swear I'd tell Bob I got the number from the musicians' union. (A tip for aspiring journalists: Any musician who wants to work in the big-time New York studios has to be registered with the union; you can simply call them up and say you want to hire the player, and you can usually get a contact.)

I rang Quine and introduced myself and my project. "Where the hell did you get this number?" he snapped. He didn't seem placated when I told him I'd called the musicians' union. "I have nothing to say to you," he said, and hung up.

I regrouped and sent him a letter. A second followed a few months later, reiterating that I intended to interview everyone who was important in Lester's life, and I couldn't imagine doing the book without talking to him. In my third--and, I promised, last--letter, I added that I was a fan, and told the story of the first time I'd seen him perform. I had stood in line with my friend A.J. for three and a half hours outside New York's Bottom Line in order to get standing-room-only tickets when Lou Reed performed shortly after the release of The Blue Mask. It was the dead of winter, and we were nearly frostbitten when we finally got in. One of the bouncers took pity on us, and when some record-company schmuck with a great table right in front of Quine left three songs into the set, the bouncer let us take this prime spot. The band--which also included Fred Maher on drums and Fernando Saunders on bass--was incredible, and whenever it came time for a solo, Reed would turn to his fellow guitarist and bark, "Quine!," and Bob would proceed to play the most amazing solos A.J. and I had ever heard. From that point on--and it's going on 22 years now--whenever A.J. and I catch up via long-distance, one of us invariably barks, "Quine!," and that night comes rushing back to us in all of its glory.

Quine called me shortly after receiving the third letter. "Alright, I'll talk to you, but I can't imagine our conversation lasting more than five minutes," he said, doing his best to be intimidating. I met him at a coffee shop in the East Village, and the interview filled two and a half 120-minute cassettes. At the end of that first conversation, he said, "I don't know why you're writing about Lester; you should be writing about me!" I told him that some day I might.

We talked many more times after that first encounter. He kept a list, and whenever he'd compiled six or eight more remembrances of his dead friend, he gave me a call. After Let It Blurt was published, I'm proud to say Bob told me several times that he loved it. His only objection was that I'd left ambiguous the specific circumstances of Lester's death. It seemed very important to him to say that Lester did not intend to kill himself, although I maintained that there was absolutely no way that anyone could prove that one way or the other, based on the forensic evidence.

Bob and I continued talking every few months about music, politics, and life; whenever the mood struck him, he gave me a call. On three occasions, fellow journalists approached and asked me how to contact him. I emailed his wife, Alice--Quine hated the computer even more than he hated the phone--and asked permission to give out his number or address. Each time, Alice wrote back, "Quine said O.K." One of these hook-ups was with the editor of this Webzine, who proceeded to do what stands as the definitive Bob Quine interview. On a fourth occasion, however, Alice failed to respond to two emails.

A reputable French journalist was coming to America to film a documentary about Lester and punk, and he was desperately trying to get in touch with Quine. He finally called me in a panic shortly before he was preparing to leave New York and return to Paris: "I don't know what to do; please--can't you help me?

I'm an idiot. I gave him Quine's number.

The next time I called Bob--to invite him on my radio show to talk about Velvet Underground: Bootleg Series, Vol. 1: The Quine Tapes--he cursed me out and said he'd never speak to me again. He hung up in the midst of my apology, and ignored the letter I sent apologizing further. And that's where our friendship stood when he died, I'm sad to say.

Despite his eccentricities, Bob Quine was not only a brilliant musician, but a warm and wonderful human being, and getting to know him was one of the finest benefits of telling Lester's life story. When Jason Gross asked me if I had any material from Let It Blurt to contribute to this tribute, I combed through some 50,000 words of interview transcriptions and culled some of the highlights of our talks to compile the following Q&A

Despite Quine's admonition, I was writing about Lester, not him, so our interviews focused on their friendship; our other chats I never bothered to tape. But as I read through the following chat, I'm struck by how much of Bob's personality comes through, as well as generous dollops of his views about music and life. I hope these highlights from our conversations will give you a sense of what it was like to talk to the man--though that incredible guitar ("Quine!") will always speak louder.

Q: I'd like to start by talking about Lester's passion for jazz. It seemed to be something that you two had in common.

I first became aware of him--I had gotten turned onto the Velvet Underground relatively late, around 1969. That's right about when one of his first pieces came out in Rolling Stone--his review of the third album. Well, I later tormented and teased him about the fact that he was talking about John Cale's "spare organ playing" on the album.

Q: Was he under the impression that Cale had played on some of that, or did he just get it wrong?

He just got it wrong. I saw the MC5 review [Lester's first published piece in Rolling Stone, a pan of Kick Out the Jams], for what it was worth, and I thought, "This is a guy that I relate to." I started reading Creem, and he was one of the very few critics worth reading. I had been playing the guitar for forty years, and I had my own opinions. I don't need people to tell me what I should like and what I shouldn't like. Critics had generally served their purpose for me. Pete Welding was a great critic--he wrote for Downbeat--and he's the one who educated me about blues. Lester was somebody that you could generally aside from the fact that his writing was witty and intelligent, he had good taste in music, pretty much the same taste as me. He would very rarely lead me astray.

Q: Did you follow him on the more extreme ends of his tastes--like his enthusiasm for Metal Machine Music, or his "Reasonable Guide to Horrible Noise"?

Did I agree with him? No. I kept reading Creem, and if you remember, in the early '70's, James Taylor, Paul Simon had a hit, Carole King--it was announced to everyone in Time and Newsweek that the '70s is the era of the singer-songwriter. I didn't quite buy that. So I became an avid reader of Creem--he was the main force in Creem--because of Lester. He would rarely lead me astray. When he did, I would let him know, and torture him about it. Once he recommended in Creem a double Grateful Dead live album and I never let him forget it: "You owe me eight dollars!"

Q: He had a weird relationship with the Dead.

Yeah--he feebly tried to defend it.

Q: How did you relate to the aesthetic that Creem was championing--were you into the whole notion of punk and the garage bands?

Oh yeah. Just the fact that he liked the Velvet Underground. The Velvet Underground had five or six fans in 1969, no matter what anyone says. I learned the hard way. I would try to join bands and they would say, "Who do you like?" And I would say, "The Velvet Underground." Even in New York, that got you nowhere. But I heard Lester moved to New York, and I was in C.B.G.B.--this was shortly after I joined Richard Hell--and we hadn't played live yet, I don't think. I was working with Richard Hell, and somebody pointed out, "That's Lester Bangs." So I went up, and he was one of my heroes. He sort of had this look of blas boredom, like he had heard it all before: "I'm a really big Velvet Underground fan, blah blah blah." Nothing could get his interest up. I had thirty-five hours of unreleased Velvet Underground tapes that I had made myself in 1969--he had been subjected to that. Then I didn't run into him anymore until we had started playing live in October of '76, and we had made our wretched little EP. Around the block, there was a little record store called Gramophone. At this point, he recognized me, and he came up to me and we started talking and started up doing something that we did a lot, one of our favorite pastimes--a pastime that is now over and done, going through ninety-nine-cent record bins. I said, "How did you like the EP we did?" And later he said, "I really didn't like it too much." I said, "Yeah, it's pretty bad--were doing an album that is going to be a lot better." This apparently impressed him, because he had had a lot of problems with people. He would champion the first Patti Smith album, and then Radio Ethiopia came out and he wasn't so enthusiastic about it, and Lenny Kaye is turning on him. This happened a lot to him, and he would always be sort of hurt and puzzled by it.

Later on--much later on, near the end--he started hyping me. He had an article out with the ten greatest guitarists in the world--things like this--and I said, "You're making me nervous, Lester, 'cause you always turn on your heroes and they betray you. You'll do that and it'll be fine with me; just don't make it personal." He laughed--he didn't have his chance.

Q: I asked him about The Blue Mask and he thought it was wonderful--it had just come out when I interviewed him, two weeks before he died.

Lester was somebody--a couple times shortly before he died, he said I was his best friend. He said that to other people; I think he said it to [John] Morthland, and he probably meant it each time. In my case, I had to keep him at arm's length; as a general rule, I keep everybody at more than arm's length. It's just what you learn from trying to exist in the world. The world is a fairly unpleasant place, and if anybody doubts me, just turn on the news tonight. Anybody who has any sensitivity or intelligence is going to be fairly damaged.

The next time I saw him, he wanted to put a band together and make noise playing "Sister Ray" and stuff. So it was me and Jay Dee Daugherty was there. We had fun, made some noise for a couple nights. He would tape the whole thing on his boom box.

Q: So you barely knew each other when you started doing the band?

Yeah. The next day, he called me up--it was a Sunday--and it was a nice day out. He asked me if I wanted to go out and take a walk, and I thought, "Wow, this guy is my hero--I get to spend the day with him." The way it worked it out--I met him on the street and he had the boom box of us playing "Sister Ray" turned up real loud. Then the next order of business was to go to the deli near Washington Square Park and get two six-packs of sixteen-ounce Buds. He was new in New York. He sat us down on a park bench with these two six-packs and vermin circling around us with music blasting, and I was thinking, "You know, this is not my idea of fun." So from the beginning, even though ultimately he was one of the few friends I had--most friends I have, the few I let in have unlimited access--he was somebody where things would get out of hand with him, if he had too much to drink. Basically, when he drank, it was the worst thing in the world. On cough syrup, he was more placid. Sometimes we would go up to the Thalia--we did it a lot in the early '80s; we would go see the Golden Turkey festivals--and he would talk about various brands of cough syrup like a connoisseur would talk about fine wine. He would say, "Romilar was good until this year, and then they put ipecac in it. Then you had to watch out." I even took his recommendations. I tried it once and I thought, "You might as well take some hog tranquilizer," because it's a depressant at best.

Q: Let's talk about the "Let It Blurt"/"Live" single: When did he start talking about doing something serious, recording with you and Jay Dee?

Well, it started out as a lark. It wasn't serious, because I was already heavily involved in making the Blank Generation record. It was something to do to have some fun and make some noise for a weekend at C.B.G.B. Basically, he had lyrics and he had some melodies. I would just work it out with [second guitarist] Jody Harris. We have a really good telepathy musically, which isn't often appreciated by people. We would verge on discourse. "This sounds like he's going for a bridge here, a chorus here." Doug Hofstra was on bass and Jay Dee drums, sort of just going along with the whole thing. The songs were good. I guess Jay Dee has a bunch of four-tracks on seven-inch reels. It went over alright. People came out of curiosity, and by the third night, there were three people there. The first couple nights, we packed the place. But he would approach me later about working with him after this project was over, and I said flat-out, "No." First of all, we made a bunch of money, and when it came time to get paid, I said, "Where's the money?" He had this look on his face, if you've ever seen Pluto--the bar tab had eradicated whatever money we had made. I think he ended up owing them money. He had morals--he knew.

The recording started out alright but Jay Dee Daugherty was really ambitious at wanting to produce it. He really is a very decent guy, but he tried to be a total tyrant and a bully about it. To me, this was an escape, because I was rehearsing and playing with Richard Hell. Whatever the music was worth, it was like pulling teeth and having root canal three hours a day. This was my chance to do something I wanted with nobody fucking hassling me. When the shit hit the fan was that we had worked out the arrangements--Jody was doing the same thing I was doing two chords lower than me; I don't know what it means in musical terms, but it's sort of dissonant and it wouldn't resolve as neatly as it would otherwise, but it wasn't supposed to. We played it back and we finally did a good basic track and Jay Dee said with a very sad smile on his face, "I'm sorry fellas, this just doesn't make it--this little puppy is gonna have to be put to sleep." I looked at him and I totally flipped out and destroyed whatever vibes were there. I brought things to a halt and, you know, I feel bad about it every time I see him, but I would have done the same thing again. He was too excited about it. He would tell everyone to come in at six and he would be in at four trying to overdub one-finger keyboards. That's immoral and it's not right. Basically, when we had the decent tracks completed, I told Lester that he wasn't mixing the fucking thing. On my end, I didn't want anything to do with it either, so have a neutral party mix it. And there was John Cale. He did a good job on the song "Live." "Let It Blurt" he sort of blew it, because the jamming at end--we did two overdub takes of me and Jody playing off each other, and what John Cale ended up using was my two overdub tracks and no Jody. I approached him about it, and I said, "We're playing off each other." And he said, "I'm producing this and this is my call." He was right, and he had more authority than Jay Dee Daugherty. So after that, I flat out refused.

Lester approached me a few times about doing it again and I said, "Listen, you do really good stuff, and you're really writing good songs, and if you want to, you should do it. But don't sell your typewriter and buy an electric guitar." The way to know Lester is hopefully through your book, through his writing, and through that record we made together. He had a self-deprecating sense of humor like I do. I use mine as a shield. His was less of a defense mechanism. He really relished one review of the record that I did with him--the guy said the critic sounded like a dying cow. He would quote that over and over. To protect him, I never encouraged him--I thought he would be a better writer than a musician.

Q: What did you think of his songs? It was clearly cathartic for him, the songwriting.

They were absolutely great and he really had something to offer. Even though you could say he is a fan--"Drinkin' port wine and singin' Sister Ray"--you can hear that in Patti Smith, she's a fan, and sometimes it hurt her music. He went past being a fan and went past that to another level. "People in the cemetery"--you know where he got that line? "Part Time Love" by Johnny Taylor. He had thorough knowledge in the right way.

You know, when we had the band that played C.B.G.B., I wanted to call it the Lester Bangs Memorial Band, which he didn't take kindly to. His name for it was Tender Vittles, which had just come out; it was a brand-new cat food. And nobody went for it. If somebody could get that together--the original four-tracks--there could be a good record. [Jay Dee Daugherty has, in fact, talked about releasing such a record.]

Basically, it was an opportunity for Lester, something he'd never done before. For me, I was in control and could do what the hell I want. If I wanted to take a twenty-minute solo, I could, or whatever idea I had. We actually sat down for like two days and came up with these lyrics and chord progressions and shit. At times, he would be appalled by the crassness of what I would do, like in "Live," in the middle, I said, "O.K., we need a bridge here. It sounds like you're singing a bridge here." And I said, "Let's take the fade-out to I've Been Loving You Too Long' by Otis Redding," and he looked at me horrified, but it worked. And it's not like things like that haven't been done before and haven't been done since.

Q: Tell me about his drug use.

I remember one time, I really saw Lester hitting the cough syrup. We went to see the Turkey festival--he must have drank two or three bottles of it. And this was like three or four movies, and halfway through he was pretty [fucked-up]. We got up, and he lived on 14th Street and I lived downtown, and this was up on 96th Street. Les said, "Bob, it's rush hour, so let's take the subway." At this point, subways had lost their appeal for me--it was part of the great adventure of living in New York--I would walk, take a cab, or take a bus. He said, "No, goddamn it, it's rush hour--it'll cost us a fortune, and this train will take us right there." I said, "O.K., but you'll be sorry. Something will happen." So we were in the car, and it was just starting up--all of a sudden hundreds of people are running past us and running into the next car and they just kept going. We looked at each other and we started running, kind of half laughing, and apparently some guy just pulled out a knife and started slashing people. This wasn't even on the news that night.

Another thing about Lester: After he had his little binges, what he'd do--and this is his idea of being healthy--he'd go to this fucking frozen yogurt shop across the street, it was up a few blocks, and he'd have frozen yogurt for lunch. That was his idea of health food. He'd be really proud of telling me that he had frozen yogurt for lunch. And I'd say, "Lester the only thing good about yogurt is that it has living organisms in it that help you, and if it's frozen, you've killed them all!" He'd have his yogurt and his B-12 shot and think he was being healthy. Then he'd go drink two bottles of cough syrup.

Q: What was your perception of how his view of New York changed over the years? He really seemed to sour on the city toward the end of his life.

When he came back from Texas, that was the worst I'd ever seen him. Apparently, near the end, he was thrown in jail and straining at the police--he's lucky he wasn't found hanging in his jail cell. He was calling them Nazis. When he came back to New York, that was the worst I had ever seen him. Gradually he was getting better, despite the fact that he died. He slipped up and made a mistake. He was generally the first month or so completely out of control. He was going around telling people after John Lennon had just got shot, "That's great," just to offend people; he wouldn't remotely mean it. He said to me, "You're an asshole." I said, "You don't mean that for a second, you're trying to shock me." He gradually calmed down. My best memories of him are of the last year and a half or so. We had a system down where I said, "I'm not around you when you're messed up." Unfortunately he had no phone at that point because he had run up a long distance bill when he was in Austin and he was living on pay phones and the only way to see him was to go over there, shout up and one out of three times he would be there.

Q: I am surprised to hear you say he could be hostile to you--the respect that he had for you is evident in his writing, published and unpublished.

I'll tell you one funny story about him--I was in his house and he would be getting piles of records together to get something to eat with all the promo copies of records. He would say, "I get more for them when I don't break the seal." He would take them to a place on Sixth Avenue right below 14th Street. And I said, "Lester, you're an asshole, there might be something good here. " He just said, "Believe me, man, it's all garbage." I kept harassing him. One day, with this malicious smile on his face, he says, "O.K., Bob, here's a pile of records I have--I was about to take them to Second Hand Rose. Let's go sit down and listen to them." By the fifth or sixth record I was getting pretty shaky. He had me begging for mercy.

The last year and a half, either he was home or he wasn't or he'd call me up on a pay phone and he would come over and he knew we would listen to records. Some of the nicest times I had with him, my wife--at that point my girlfriend--we finally got to know him pretty well. I lived on St. Marks Place and he spent Thanksgiving with us when he would have rather have been with [a girlfriend]. He spent New Year's Eve '81 into '82 at my house and he would have rather have been with her. It's difficult to make things like that interesting, but these are the memories that I like. I was still friends with Lou Reed a this point--I had done The Blue Mask and I was actually friends with him for a while, which was a very bad mistake.

Q: That's fairly rare; I don't think I've heard that sentence before: "I was friends with Lou Reed."

Lou Reed was one of his heroes. Certainly he liked a lot more Lou Reed records than I did. It's like Take No Prisoners--that sounds like really bad Jerry Lewis to me. The only Lou record he didn't have anything good to say about was Growing Up in Public. So I was friends with Lou Reed about six months before Lester died and I was trying to somehow get them together. Lester was slightly envious that all of a sudden I was going out and seeing movies and going out to eat with [Lou]. I was really stupid, though; the first version of The Blue Mask which you never heard was much better. It's the same record but he's doing live vocals and he's not trying to croon and he's using some really heavy-duty obscenity--like the rape thing and "The Gun" is powerful. He cleaned up a lot of it. Because of my loyalty to my alleged friend at the time, I didn't play Lester that stuff cause he--Lou--wouldn't have wanted me to. Finally at Thanksgiving, I got the permission to play Lester the mix--he sat there with headphones and he liked it; he said it was good but the lyrics were weak. Lou Reed asked me what he thought of it and I said, "He really liked it but he thought some of the lyrics were weak." It was probably the worst thing I could have done. I was just so infatuated with being able to hang around with this guy, my hero. And I made a good record with him.

Q: After all this time, Reed still couldn't take Lester's criticism.

Coincidentally, my friendship with Lou Reed ended with Lester's death. I'm going to skip ahead. When Lester died, I got the news Friday night. The next day I was sort of stumbling around in a state of shock. It was a sunny day; it was Saturday. I went up by his house and the window was open. I thought, "I could go up there and bellow his name, but I don t think he's coming out." I was in a state of shock, 'cause I never had a friend die before, and I was just sort of a walking target. I was walking by Gramercy Park, and this very evil-looking black guy, like an old gangster from the '40s, he had the phone cradled in his arm and I was walking by and he had a cigarette in his mouth and he grabbed my collar with one hand and points to the cigarette like he wanted it lit. I was too numb; I did it. If someone would have done that to me on a normal day they would have gotten hurt. Then I went over to Lou Reed's house. When I told him that Lester died, he didn't believe me. That marked the end of my friendship with Lou Reed because he said, "That's too bad about your friend." But then he launches into a forty-five minute attack on Lester. He's an egomaniac and that's the way he is and that's why he has no friends. If you're not a yes man, you're not his friend. He respected the fact that I wasn't a yes man, but ultimately I had to go.

He mentioned the article in Creem when Lester describes Rachel [Reed's transsexual lover]. He says, "Do you understand, Quine--this is a person I was close to. And he is calling her a creature and thing.'"

Q: Yeah, but Lester was under the impression that Reed had her on his arm precisely because she was a creature. And Reed made her fair game by writing songs about her.

For a while, when I was really like, "Lou Reed' s my pal"--I was over at Lester's house and I said, "He's just a normal guy." Lester said, "Bob, Lou Reed is not normal." He pulled out the record of Walk on the Wild Side--with the pictures [of people in drag]--and he goes, "See this? This is a guy, Bob." It put things a little in perspective for me.

Q: I learned about the Velvet Underground because of Lester's writing. It made me fall in love with that music. Cale told me, "Lester kept Lou Reed afloat for ten years."

It is my humble opinion that Lou Reed is an asshole. You can give this reason or that reason why he acted the way he did--he just kept going on and on about Lester. Lester had written this wonderful heartfelt obituary of Peter Laughner, where he ended it saying, "I wouldn't walk across the street to spit on Lou Reed." Lou had gotten a copy of that and he was reading this to me like he was looking in a mirror--that was the end of the conversation. When I left there, I said, "You know, I don't think I can be friends with this guy." I tried to back away from the friendship, which is something you can't do with somebody that paranoid. I tried to do it over a six-month period, but I had to pay.

Q: But you did two other albums with Lou Reed, right?

He mixed me off Legendary Hearts; I'm barely audible on it. He did the Live in Italy record, which is not very good. If you read interviews with him, he's like, "I know I am very good; quote me." You know the song on Legendary Hearts called "Home of the Brave"? It's about people that are gone, people that are dead. There aren't many places for solos in that record, and I said, "I want to take a solo in this one." And that sums up my feelings about Lester. That's pompous of me, but . What I did was I went direct through the board and it came out totally naked and brutal and what he did, he added a bunch of fucking slap-back echo to it. But that was my expression of my sense of loss. I sound like a pompous asshole.

Q: Reed was jealous of your guitar playing?

It is as simple as that. The reason I felt betrayed was I bullied him into playing guitar I told him straight up if he doesn't play guitar I told him straight up. I would force him to take solos. Then he got his confidence and he turned it into a competitive thing. If there is a competitive thing, there is no way I am going to win. Not when he is telling the guitar guy to mix me out when people can't hear me taking guitar solos. When he keeps me out of a mix to make sure I'm not being heard, he's an asshole. I finally ran into him a couple weeks ago, and I just kind of walked by him. I wouldn't say anything and walked out and he turns to the sales guy and says, "There goes one miserable motherfucker." He tried to get me to come back and play with him for two and a half years, but I couldn't take it anymore. He had a mutual friend ask if I would ever play with him and I said, "No, I'll never play with him ever again." That's when he would start saying nasty things about me. Basically his stock answer would be, "Quine is a very very, very, very sick individual," and that would be the end of it.

It's an important story about Lester. You know, Lester, he would hold people up. Lester was sort of like me: he saw things in terms of good and evil. If somebody didn't live up to expectations, then they had betrayed the gift.

Q: I'm not sure I understand the Lou Reed obsession. Why was he so fascinated?

Well, it's the same for me. It's like Little Richard--I've never met Little Richard, and I never bothered to see him, and he hasn't done anything good in forty years. But if he walked in here, I would go fucking stone cold. I don't give a shit about poetry or anybody's lyrics--if I don't like the music I'm not gonna bother, like the social issues the Clash are singing about.

Lou was, and still is--when you draw the line on his good stuff--he changed my life completely. Long before the Jefferson Airplane were talking about pot, he had a song called "Heroin." This guy did not mess around. And that's the reason. And once in awhile--he was not the same person I knew in 1969, but you saw sparks, and when you saw them, you knew. Lester never gave up on Lou Reed. Iggy Pop approached me once or twice about playing with him, but Iggy he had totally written off. He said that this guy was a moron and he would never make another good record. I would argue with him; I would say, "Listen, he has another record or two in him." He would say, "No way." Today, interesting enough, Raw Power is being reissued in a new Henry Rollins remix. I have a feeling it's inferior. But I'll have to buy it. Lester said to me once, "You know what I do when I go over to people's houses? I look and I check their copies of White Light/ White Heat, and a lot of times they haven't been played." He did it to me. He said, "Bob, this is mint!" I said, "Lester, how many copies do you think I've worn out, you moron?" I literally had worn out seven or eight copies. I paid for it. It's hard to imagine how completely unappreciated they were. That was the link that connected me to him--the fact that he gave this record a decent review--whereas [Rolling Stone's] Ralph J. Gleason would be singing the praises of the Jefferson Airplane.

Q: You know the song "Rock 'n' Roll"--Janie's life was saved by rock and roll--who believed it more, Lester or Lou?

I think in Lester's state of mind, near the end, that Village Voice Pazz and Jop Poll, he was like, "Maybe something better will come around," but I don't have him around to tell me anymore. I think at this point things are better in that instead of people just paying lip service to the Velvet Underground or doing cop-outs like the wretched Cowboy Junkies or something--it's been enough time now that another generation has sort of absorbed it. I got so immersed in it that I absorbed it. Sometimes when you hear a song by somebody like Yo La Tengo or Stereolab, they understand that thing.

Q: Some of his friends insist that at the end, Lester had given up on rock 'n' roll. You don't think he would have?

There is no telling. Just by accident I happened to see him the last day, Thursday night. I bellowed up there and I happened to have a tape of Destiny Street, which was finally mixed after a year. He was there, [his girlfriend] had been there and left. We listened to it. Maybe the reason he died was if he was writing something, like finishing a book, it usually meant he was taking a lot of speed and staying up for like five nights at a time and no matter how strong his constitution was, that weakened him. He had the flu and he fucked up. I started to play the album--he went into the next room and had a handful of something with a stubborn, stupid look on his face and washed it down. I said, "What was that?' "Valium," he said. We listened to the whole record in silence. It looked to me like he was sleeping, but once in a while, like at the end of "Ignore that Door," he would give a little smile. I'm glad I got to play it for him--he liked it. He was frustrated and but he wasn't particularly unhappy--certainly by no means did he intend to kill himself. If anyone suggests something like that it's a complete lie. Despite whatever damage he may have done to himself, he was just as alive and as vital and as humorous and funny and as smart as he ever was. One of my nicest memories of him is one of the things I kept. I kept very little. I took some of his inhalers, his cough syrup. I almost took his TV Guide, because he died on a Friday, and TV Guide starts on a Saturday, and there was a TV Guide waiting for the next week--he had invested thirty-five cents in it. He had one of these hand puppets, the Cookie Monster. One of the last times I saw him, it's my nicest memory of him--he did a little thing with the Cookie Monster, like a ten-minute thing. I wish I would have taped it. I have that puppet still--I washed it.

One of the eerie things about seeing him that day: His place was a mess, everyone knew that. I went over there and hadn't been there for a week, but the place was completely neat. For the first time since I've known him, his records were filed. There were no records on the floor. What does that mean--don't clean up your house or you'll die? He was definitely a little hostile and a little surly. He said, "Let's go out." I was sort of wary of him. So we walked out his door and we started walking down Sixth Avenue towards Eighth Street. It was sort of a nice and the vermin was out--that's one of the unfortunate thing about a nice day in New York--and he said, "This is going to be a bad summer here." We walked past the B. Dalton on Sixth Avenue and Eighth Street. He would never walk by without saying that it's bad and evil. It was set up to make you very uncomfortable. I used to tell Lester about the McDonald's down by City Hall where the chairs were slanted so you would get out. He hated that bookstore. So we turned left, walking up towards Eighth Street to a place called Eva's--sort of an Israeli-type restaurant. We used to go there fairly often, and he said, "You want to go in and get something to eat?" In fact, I did, but I said, "I'm really not hungry. I'm going to go ahead home.'' So when we hit Fifth Avenue, he turned, and that was the last I saw of him. Sometimes I think about it, like, "What if you would have had Wheaties instead of Cheerios on June 5, 1972?" You never know.

For awhile, I hung around with Billy Altman and John Morthland just as surrogate Lesters, but really we had nothing in common. I'm not Lester and they're not Lester. The thing that I had in common with Lester was that I was obsessed with music and he happened to be good because he was really bright, really smart, a really great soul, and he happened to be totally obsessed with music.

I went to the little wake thing where his ashes were in the next room. I had nothing to say. You heard the story about Sid Vicious' ashes? Lester told me this story. Sid's mother was at the airport bar with Sid's ashes and she was talking to someone. She knocked it over and they spilled all over the floor with all the cigarette butts and all the cigarette ashes. Perfect end to that story. For about two or three days after that happened, there were red necks running up and down trying to find punks to kill. But Sid Vicious never killed that girl.

Q: Tell me more about your friendship with Lester--what was the interaction like?

My humor was more cynical and farther out than his, even though he was wittier than me, I think. I deliver things deadpan, and I've been doing it so long that I have to watch out who I say what to. I was telling Lester about a Voidoids rehearsal where we were fighting about everything--everything just stopped and I said, "Listen, goddammit--you guys barely got out of high school! I'm a college graduate! Not only that, I've been to Law School; I have a law degree. Therefore I'm right and you're wrong!" Even they understood the humor, but Lester just looked. I said, "Lester, do you understand the humor?"

Q: Did you ever say something that just totally devastated him?

I pulled this shit off with a straight face, and if I said things that were morally repugnant to him, he would--which leads me to another story. About 1978 or '77, Harvey Mandel, one of my favorite guitar players and a very underrated person, he was going through a streak of bad luck and, like, playing the Bottom Line with a lead singer. But he was really amazing. And I was taping this stuff, and Richard Sohl was there, Jody Harris was there, I can't remember who else. And I said, "Lester, you know why I'm taping this?" He goes, "Why?" "'Cause I'll take this shit home, and I'll fucking cop it, and I'll rip it off. This guy doesn't have a record contract. And I'll have this shit; I'm recording right now. I can steal this shit, and he won't get any credit for it, and I will." And he looked at me with complete horror, and I said, "Lester, I am kidding." So there was shit like that.

He would always call me when people died to get my reaction because I guess I delivered the first time. He called me and said, "Elvis died." I said, "Oh no--no more movies like Clambake." Sometimes I would offend him. His little pal Peter Laughner--I met him once or twice--he was a total asshole to me. Basically, people explained to me later that he was jealous because I was playing with Richard Hell and he wasn't. I said, "Well, when your friend Peter Laughner kicked the bucket..." He said, "What do you mean--kicked the bucket?" I said, "I don't know--he's your friend--that's good. I used to read his stuff." He was perhaps more musically talented than Lester, but he never overcame the fan aspect to come into his own.

I remember the first night I played with him at C.B.G.B. He was saying, "Hey you fucking homos!" And I dug that, because it was politically incorrect. As time went on, as he got more and more involved in the Voice. He became more and more politically correct, or was trying to be. Like some of the other conversations I had with him about crime or womens' rights--he was really attempting to be a more sensitive, socially conscious guy. He had something very '50's about him. If you categorized him, he was much more a beatnik than a hippie. Everything about him was much more '50's than '60's, even though that's when he made his mark. Even down to as far as his sexuality goes, I remember I'd find these magazines around his house--he wasn't above buying these skin mags--but he wouldn't even buy something as blatant as Playboy or Penthouse or even Hustler, but things like Sir or Cavalier or Nugget. When we were cleaning up his house, that's what we found. We didn't find any gay frolic magazines. And I said, "Hey, Lester, if you're gonna spend the money, go up to 42nd Street and get some really hardcore horrible shit, you know? This is the golden age of porn!" And he said, "No, that stuff really turns me off."

Q: I found something in his notes, attributed to you--it said simply, "Quine says: Let them smell the pussy juice on you.'" What was that about?

I remember what the pussy juice quote was! He wasn't getting laid at all, and he went through long periods like that. And then he and his friend just sort of did it one day. And I said, "Oh well, that will turn the tables now for ya, because they'll smell the pussy juice on you." It's either feast or famine with work or girls or anything else. Once they smell that pussy juice on you, you won't be able to fight them off. It's amazing that he really took it to heart. I guess I was a real guru for him.

Did I tell you the story about the favorite Chinese restaurant where we used to eat? I would steer him there, because the place was always empty, if he was in bad shape; there wouldn't be a lot of people to witness whatever atrocities he committed. His favorite story, which he always repeated because I got a kick out of it, there was some old couple, they were paying their check and leaving, and the waiter came up and said, "Did you enjoy your meal?" And they said, "No!" And left. He really got a kick out of that.

One of the last really nice times I had with him, [his girlfriend] and some guy and Lester came and picked me up and they took me to this place, a place called Smokey's. There were three of 'em; the one we went to was around 9th Avenue and 25th Street. It was a barbecue place, but if you drove by it, it looked like a Burger King or a McDonald's, and you'd never go in there. And they took me there, and they had that mesquite piled up; it was the real thing. He came from a background of consuming large amounts of Mexican food, so he felt pretty confident about his ability to consume hot sauce. And I've won bets eating hot sauce. And there were signs all over the fucking place about--you know, we got some ribs, and it says--"Beware: We have mild, medium, and hot. If you have our hot, you've gotta fucking sign a waiver." Well, they didn't say exactly that, but, "Do it at your own risk." And that was like, "Ha ha!" So I have this vivid memory--we each were biting into these ribs; I was sitting right across from him, and our eyes bugged out like the Three Stooges or something. This shit was so brutal; we were impressed. This shit--I didn't rinse my mouth off immediately thereafter, and I had a red ring around my mouth for about a week where the skin blistered from this stuff. This was the real shit. This is the sort of stuff I remember.

This is another story: I had to teach him to respect my privacy, and he did. If I ever got brutal with him, he'd back off. I don't know if I ever told you about this, where he rang my bell for about forty-five minutes one morning. This is when he first started seeing [one of his girlfriends]. It was Saturday morning; my girlfriend and I were sleeping, and unfortunately people had access to get inside the first door to another door there and buzz at will. And somebody was ringing my buzzer, like for fifteen or twenty minutes. And it's like 10 in the morning! I got a fucking hammer, I went downstairs, and he's beaming. He has a big smile on his face: "Hey, c'mon outside, I want you to ." I said, "What the fuck are you doing?! What the fuck is wrong with you?! Get the fuck outta here! Don't you have any respect for people's privacy?" He never did that again. He was just standing out there, looking sort of embarrassed.

Other times, I remember once--I'm a fairly twisted person, but I'll say to my credit, I don't bother people when I'm fucked up, I just leave and just go off by myself. I remember once I was walking up Sixth or Seventh Avenue and he came up behind me; he was with either the girl that was the hooker or the other one, the one who found him dead. And he said, "Hey, how ya doing?" And I just said, "Oh, hi." I wasn't real friendly. I said, "I'm really fucked-up. I'd like to hang around with you; I just have to walk this off. I'm really feeling fucked-up." And he said, "That's totally cool." He didn't feel paranoid about it; he just totally understood. For what it's worth--and it's worth something to me--I just wrote down every little trivial thing.

Q: Help me fill in some of the blanks about some of the people that you knew in common. What was his relationship like with Brian Eno?

He interviewed him a couple times and he respected him. But ultimately, I disagreed because he liked Eno's rocky albums, which I didn't really like. I thought ultimately he came into his own with the ambient stuff. In fact, when Lester near the end was grousing about music, I had an advanced cassette of On Land.

Q: You're on that album, right?

I'm thanked. I started to be on the album--it started as a vocal pop thing--but then it evolved into an ambient thing and I was gone. I did encourage him to go on with it and he thanked me for it. When Lester went to his mom's funeral, he borrowed the electric Miles Davis--he dismissed all of his fusion. I would argue that, "You have got the Velvet Underground, the Stooges, and this Miles Davis stuff post-1972--this stuff is coming right out of the Stooges!" I got that point across. He borrowed the tapes of that to listen to on the plane. I think I went with Lester to see Miles Davis' comeback in 1980--the Newport Cool Jazz Festival. Basically the way both of us felt was, "This stuff is no good." But we were both wrong before, and it's too early to tell. Maybe I got together with the two of them once or twice. They didn't really hang around together. I talked to Eno a lot about Lester dying. He was one of the few people I used to hang around with. I remember about a month and a half before he died, I was up at 48th Street selling guitars, and Lester bounds out of this Popeye's Fried Chicken, and I said to Eno, "What the hell is this guy eating lunch for? He's gonna die."

There are certain dates I remember--February 3, 1959. I was a big Ritchie Valens fan. November 22, 1963. April 30, 1982 [the day Lester died]. My father died last year, but the circumstances were not traumatic; he was 89. Those are a few dates that stick in my head. Later that year, the Tylenol poisoning. AIDS didn't really exist--it was just this rumor of something--what would he have thought about that? What would he have thought about CDs? He would have fought them tooth and nail, just like I did, and then being the music junkie, he would have bought the first eight Byrds albums. He probably would have really embraced rap music for a minute and then realized what hateful, cretinist, subhuman garbage it was. What he would have done is write a twelve-volume biography of me. It's too late to help Lester--but you can do it; you have access to my baby pictures, drawings I did at school. This is what Lester would have wanted!

Q: Was the record with Fred Maher, Basic, done before Lester died?

No, that was done in '83-'84.

Q: That's one I think he wouldn't have liked.

I would have sat down and explained what I was doing. Basically there is a lot of dead space in that record. A lot of the questions that you asked me about his ideas and stuff, Billy Altman or [John] Morthland can give you better because they're writers. I'm semi-articulate, but I am basically just a guitar player, and I see things from that point of view. The one thing I had in common with Lester was that I would have collected butterflies, coins, or I would have been a serial killer if I hadn't discovered music, and I would have gone at it three-hundred percent. Fortunately, I turned my interests towards the guitar. I was a very lazy kid with no direction, but something kept me going seven or eight hours a day with no lessons. No one would teach you how to play rock 'n' roll back then. If you went into a guitar teacher in the '50's and said, "I want to learn how to play rock 'n' roll," forget it. Finally, someone showed me how to play like a rock star. I went to Berklee School of Music for a while, but I learned nothing. Even by then (1967), I had been playing for ten years. My ability to play so far passed my ability to read.

Q: How did Lester know Laurie Anderson?

That connection I sort of was responsible for. He had some photographer friend of his that he knew, Marcia Resnick. I was friends with Marcia Resnick. I said, "She's one of us. She's a genius and cool--someone that you should know." He would spend many hours trying to educate Marcia. When he died, there were piles of his records all over her floor. She lived in the loft down on Canal Street immediately below Laurie Anderson. In fact, one of the last nice times I had with Lester, in August '81, I said, "I'm going over to see Marcia Resnick. We're going to hang out and get a little supper," and he said sure, he'd come. We had a nice quiet dinner in a bar--and he didn't drink. We went back to his house and we watched this movie. Laurie Anderson lived upstairs and somehow--she was certainly unknown at the time--they introduced her. Meanwhile, Marcia Resnick got out of control a little bit herself. Richard Lloyd moved into her house and it was total chaos and insanity erupted. He would come over and visit Marcia and flee up to Laurie Anderson's place. Since Laurie Anderson couldn't really play anything, and he couldn't either, they would make music together. In fact, the last day I saw him, that album [Big Science] had just come out. Laurie was his friend and he said, "This is good." And I said, "It's garbage--shit." The fact is that everything I have ever really liked in the last thirty years is stuff I hated at first. I had to eat my words two years later.

Q: It's a small world, eh? It's odd to think of Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson as a couple now.

Don't ask me about that--from knowing the guy, maybe it is possible to walk the line and actually be bisexual. I can see somebody functioning bisexually . To me, Lou Reed clearly falls into the other, despite the fact that he's been married twice. My theory is if he accepted it, there would be less conflict. He grew up in the '50's, when being gay was not something remotely cool to say. I think he grew up with this inbred thing and that's part of it.

Q: When Lester toured with the Clash to write his famous piece on them, the Voidoids were opening. What was that like?

I barely ever saw him--the Clash traveled separately from us, and he traveled with them. Sometimes we would be in the same hotel, sometimes we wouldn't. I don't even think I had a meal with Lester. I would see him in the audience, sometimes backstage. I remember once, in fact, he came in and sat down and talked to us for about and hour and a half. I had the impression that they were sort of half-laughing at him behind his back. One of the only times I flipped out on stage, I smashed eight people in the head with a guitar--he was standing right there and I was talking about it with him the next day.

Q: I've always wanted to ask you about a story I heard once regarding the solo in "Blank Generation." I read that Richard Hell was strangling you in the studio as you played it in order to get you in the right--or wrong--frame of mind.

Generally my first take was the best and then they would get worse and worse. So he would goad me and push and torment me. Not physically, just so that I would get so pissed off at him so that it would just come out. Twice, live, he got so pissed off that he flipped out and destroyed all the equipment on stage. I would not leave the stage until everyone crept back and started another set.

Q: We sort of touched on this earlier, but it might be a good place to wrap it up for today: Why do you think Lester kissed your ass in print so much?

The fact is that critics like me because I am a cult figure--which means I'm not really successful. I'm not big enough of a target. About every five years, I do a record with someone and magazines are interviewing me again. It works for me a lot where I can do no wrong. If I'm on somebody's album like a Lloyd Cole album, and the guy doesn't like it, Lloyd Cole gets the blame. If the guy liked the album, he probably would have given me the credit.

I'm not a major success or anything, but I seem to have been a survivor, and I play better than I ever have. When I look around at other people from the era, I seem to have done O.K., and the reason is I truly don't give a fuck. I honestly believe that rock 'n' roll was pretty much finished by 1961. The atrocities I've pulled... I just don't give a shit, maybe because I'm such a lovable genius.