WHY MINIMALISM HELPED DESTROY INNOVATION IN MUSIC

|

|

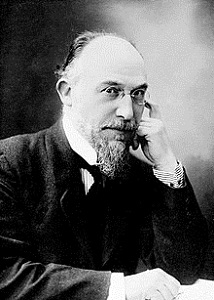

| Erik Satie | Steve Reich |

A Short Essay, A Short Essay, Essay, Essay, A Short, A Short...repeat as necessary

by Dr. Gary Gomes

(August 2018)

Minimalism has been touted by many as the last great innovation in music, following the extremes of the romantic and post romantic era. From roughly 1910 to 1970, modern Western art composers experimented with many new formats, including free tonality, serialism, dodecacophony, tone clusters (going back to Ives in the 1800's), polyrhythms, masses of sound, electronics, chance music, free improvisation and musique concrete. Actually, we can trace the experimental music tradition into two contemporary founders--Ives, who pioneered most of the radical, non-linear thinking that became prevalent in the first half of the 20th century and Satie, the originator of both ambient music and minimalism. The one thing these innovators shared was that, during their lifetime, nobody paid much attention to them. Ives was mostly engaged in the insurance business (and developed ideas his father George Ives had pioneered), while Satie, although know for being a local celebrity in Paris, was largely ignored by the formal musical establishment. His piano piece Vexations was perhaps the first repetitive minimalist musical composition (along with Ravel's Bolero), and Satie set the foundation for ambient music with Gymnopedies, which he wanted to be experienced as background music, urging art patrons to ignore the music and look at the paintings. People like Partch, with his interest in microtonal scales and experimentation, could be seen as an independent, unconnected extension of Ives.

The experimental edge in music ebbed and waned throughout the 20th century, with some breakthroughs occurring in 1910's - 1930 (Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Varese, Ornstein, Cowell and others), then a conservative trend happened around 1930-1950. In 1950-1970, all hell seemed to break loose internationally, with the Second Viennese school becoming accepted, and studied, and further innovations triggered by Messiaen, Stockhausen, Cage, Berio, Boulez, Xenakis, Ligeti and many other composers becoming the foundation for extreme experimentalism. Many of these were produced by followers of Cage and Stockhausen, both of whom led to the development of minimalism (Cage's "4'33""; Stockhausen's "Stimmung" and "Mantra" are examples), but true minimalism as we know it today came from La Monte Young and Terry Riley.

Young developed extremely long interval musical forms along with unusual instruments (like the Motorola Scalatron) and performances could last for days. He was a skilled performer in his younger days and developed--as many innovators do--a small cult of followers devoted to long tones, tuned in just intonation. Riley was an early affiliate of Young, but modified his combo organ for just intonation and often used tape loops (pioneered by Pauline Oliveiros years before) and held all night concerts in Europe. Both of these musicians had a profound impact on rock music- Young attracted John Cale, whose Velvet Underground influenced Can from Germany, punk, Eno and trance music, while Riley was a direct influence on the Who, Soft Machine, Daevyd Allen, Robert Fripp, Eno and others.

A little after Young and Riley, the two other prime movers of minimalism appeared--Steve Reich and Philip Glass (David Borden and Tom Johnson were also also active, but these two seemed to make the biggest impact). Reich, as Riley did in In C, set up a system, first with electronics ("Come Out"), then with keyboards and a pulse ("Four Organs"), later with larger ensembles (for example, "Drumming").

Glass was less likely to let things fall to chance and wanted a propulsive repetitive music that he could control. He formed his own ensemble, first with Farfisa organs, adding deliberate repeating note runs to the compositions, eventually enlarging his ensembles to include singers, orchestras and synthesizers, developing into massive works like Einstein on the Beach.

The downfall of minimalism started when composers decided this was a viable career direction and the music-more rapidly than most innovations--it became mainstream rather quickly in the 1970's. Aided in part by the semi-minimalist Tubular Bells and John Carpenter's soundtrack work, minimal themes entered the public arena fairly easily. Horror movies had previously let atonal works into public consciousness (the TV shows Thriller, Twilight Zone, Outer Limits and Hammer Studio movies allowed these in).

But the rapidity of the course to acceptance of this kind of music was extraordinary. We can relate it to a few trends that made the 1960's-1980's ripe for the expansion of minimalism:

1) The acceptance of the second Viennese school-and its later offshoots- as a legitimate musical tradition was hard fought and rather grudgingly accepted. The dominance it enjoyed after WWII seemed to be founded on a well developed sense of guilt that regimes like the Nazis and the Communist banned progressive or dissonant works of music as "decadent" or "elitist" (Shostakovich turned from more progressive compositions like "The Nose" to state-approved works fairly early in his career, however, this people's music movement was reflected in the 1960's, early 1970's by people like Cornelius Cardew, who wanted songs people could relate to). The neo-classicist movement in Europe and the U.S. seemed to parallel a return to more traditional musics, either because of economic conditions ('let's make music entertaining') or a desire not to upset people. Oddly enough, all of these reactionary movements seemed to have started in the late 1920's-early 1930's- George Antheil famous Ballet Mechanique premiered in 1925. Varese and composers like Messiaen, Webern and Vermeulen still wrote unusual pieces, though they were largely ignored. Post-war Europe, the United States, Japan and South America developed an interest in serial and post serial work, sometimes for political reasons--and because some composers organized together.

2) With this acceptance, increasingly complicated methods of music and grand experimentation became the norm among accepted musical establishments in the 1950's to 1970's, starting with Stockhausen, Cage and Boulez most prominently, at Darmstadt. Multiple orchestras, collaborations with free jazz (Penderecki and Bernd Alois Zimmerman, among other), free improvisation, collaborations with rock (Pierre Henry and David Bedford, among others) were part of the music of the day, culminating in electronic collaborations.

3) Electronic collaborations and multiple methods of composition (such as Xenakis's and Cage's computer generated methods and selection) were paralleled by the increasing use of the studio as a musical instrument in rock music. The acceptance of anything as a compositional method also opened the door for "getting back to basics" and setting up systems for exploration.

4) The thirst for tonal (key centered) music in the classical world was palpable. Bernstein spent several episodes of a public television series analyzing Schoenberg and the second Viennese schools exploration of systems in order to anchor all music to tonal centers. The foundation of an intellectual framework moving towards tonal systems was evolving.

5) Young and Riley actually developed out of exposure to Stockhausen while Young, in particular, seemed to have something in common with the films that originated in the 1960's that just took one picture of a building and played it for hours. Young, Reich, Riley and Glass also benefitted from developing systems of compositions. Young worked with very few slowly transitioning musical tones, rediscovered just intonation (which was known before, but had been successfully put to rest by Bach in western music as it would not allow for key modulation without many, many keys or frets), Just intonation also resurfaced with interest in Indian music (it is not exactly just intonation, but it is close) and music from other cultures around the planet, which allowed for microtonal note intervals. Riley was more playful--he set up his methods as bases for improvisations, while Reich started out doing electo-mechanical processes (manipulating tapes, swinging microphones back and forth until they stopped), and Glass developed an arpeggiated system of repeating figures that added and subtracted beats, but had hooks (as in pop music). It is interesting to note that like much of Western art in the 20th century, much of minimalism started mining and appropriating ideas from international music (India, Africa--in the case of Reich) and appropriated these other music forms for itself.

6) Popular music was evolving in a similar direction, with repeating verses, fade outs, and outright appropriation of minimalist ideas by artists like Soft Machine, the Who, the Velvet Underground (early loop experiments, although Soft Machine experimented with these earlier, but did not record them), Pink Floyd, Can, Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk, Mike Oldfield, Magma, Roxy Music, Eno, Carla Bley and many others worked with Riley, Young, Reich and Glass inspired concepts.

All of these, and the foundation of minimalism being in New York, helped spread minimalism to other centers of the world. After minimalism (but considered an offshoot), Glenn Branca also fiddled around with setting up guitars in just intonation, but making no further progress than Harry Partch did with his super scale systems--they used amplifiers and the music was notably louder than Partch or Riley, but the same ideas were being regurgitated.

Minimalism was an easy out for creators--it was internationalistic without being perceived as originating from Europe; it was tonal (thank God, all those awful dissonances were gone), it was a process, so it was organized, and in Branca's hands, the music had the excitement of a rock concert. Trance inducing, soothing yet exciting--I can understand why Cage accused Branca's music of being fascistic, although I think Cage has analyzed it wrongly.

However, the main problem with minimalism was not fascistic tendencies, but the idea that you could have a serious music that, by its steadiness, could lull you into a trance, could essentially cease the mind thinking about music and what new concoctions one could create. It does the opposite of stimulating thinking. It is revelatory, but slow moving, like a Wagnerian opera; it appropriates from other cultures without needing to acknowledge it. And it has become a school, robbing composers of the need to make their own voice. It is anathemic to self-expression.

This is not to say that minimalism has not created some great works. But it has developed into a creative dead end that lulls rather than inspires. Creativity in music in general seems to lack a spark nowadays, and I don't think that is just me being an old man crank. Minimalism strives to constrict and control sound, when we should be liberatng sounds. Everything is categorized and (to overuse my favorite expression) Balkanized. Camps are quite comfortable being separate from each other. That's lethal to creativity.

This debate may, in fact, be long over as minimalism has become an idea within music. But nothing salient has emerged to move music forward, and that is what I am waiting for. The first half to sixty years of the twentieth century produced a plethora of new musical ideas, some barely touched. Perhaps it is time for someone to pick up the threads of what was created then, and make something NEW! 'Let's try something new,' to quote Slonimsky.