The Underdog Rising: Mingus in the 1950's

By Tim Ryan (April 2000)

So many of Mingus' greatest moments come when he goes for broke, playing sounds that haven't been heard before, with an intensity and artistry that will never be matched. The 1950's would be an important time for Mingus. In a decade he would go from employment as an L. A. postal worker to becoming generally acknowledged as one of the finest bassists and composers in jazz. He would establish a record label, jam with his heroes, and change the rules about bass-led combos. He would also create some of the most stunning, disquieting, and, above all, enjoyable records in the discography of jazz.

Mingus' earliest recordings were with Louis Armstrong in 1943, and he made his first solo dates in 1945. However, much of that music is at best, difficult to find. The first recording that garnered Mingus widespread attention was "Mingus Fingers," a tune he composed for the Lionel Hampton Orchestra that was a national hit in 1947. Mingus remained a sideman for most of the decade, and as the 1940's became the 1950's, the then 27-year-old Mingus had become alienated from the music business, and went into semi-retirement.

Mingus' first big break of the new decade came when he became a member of Red Norvo's pioneering vibes-guitar-bass trio in 1950. At the time, he had quit music, and was delivering mail when vibraphonist Norvo sought his services. The group's popularity in the cool jazz realm created a bigger visibility for the great bassist. The music the group made (much of it collected on The Red Norvo Trio With Tal Farlow and Charles Mingus [Savoy]), enjoyable as it is, sounds a bit quaint today. All three players are top-notch instrumentalists, and many of Mingus' musical ideas would take flight from his participation in the trio (check out the percussive bass playing on "Time and Tide," which sketches a rough blueprint for Tijuana Moods).

Mingus relocated to New York shortly thereafter. The most dramatic event in the early part of the decade would be his establishment of Debut Records, with Max Roach and his wife, Celia in 1952. A number of artists tried their hands at running labels, but many of them (Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck) were established stars. By contrast, Mingus was a relative up- and- comer. Debut Records gave Roach and Mingus a chance to sign new talent (the roster would include debut records from Paul Bley, Hazel Scott and Thad Jones) and release their own music. The box set, The Complete Debut Recordings (OJC), collects the phenomenal, revolutionary work of the label in its six year run.

The quiet but assured elegance of Strings and Keys (available on Debut Rarities, Vol. 2 [OJC]) is an early sign that Mingus wouldn't be playing it safe in the 1950's. Recorded in Los Angeles before Debut was even in existence, the record is influenced by the Ellington/Jimmy Blanton piano/bass duets in the early 1940's. Spaulding Givens' flowing, open piano work adds class to the tunes, and Mingus operates as both rhythm provider and, occasionally, as a second melodic voice. The rippling of "Blue Tide" and the restrained takes on such standards as "Blue Moon" and "Jeepers Creepers" make Strings and Keys a happy-go-lucky, but still sophisticated recording.

Debut Records allowed Mingus to release mini-albums and singles to give the world a sample of his growing compositional abilities. The titles "Extrasensory Perception" and "Precognition" display Mingus' interest in psychology. By delving into the subconscious, Mingus proves his ability to compose in the big leagues. With singer Jackie Paris, Mingus also proved to be able to write some penetrating lyrics to go along with the music. "Portrait," "Make Believe," and "Paris in Blue" are at turns conversational, playful and elegant (these tunes are available on Debut Rarities, Vol. 4 [OJC]). Mingus would reach his lyrical apex the next year on the romantic/political "Eclipse," a song he had written for Billie Holiday. Recorded with an octet for a four-song Debut release, "Eclipse" demonstrates not only Mingus' way with words, but also a stunning ability to compose for larger ensembles while maintaining an improvisational edge.

Nineteen fifty-three was a huge year for Mingus. Debut began to be acknowledged as a creative force in jazz, and Mingus was more and more in demand as a sideman. He got the chance to play with his idol Duke Ellington, but was promptly canned after fighting with other orchestra members. He was tapped to play piano on a recording of one of his own compositions with Miles Davis as the leader (on Blue Haze [Prestige]). While recording for Debut, Mingus worked with Oscar Pettiford's ensemble (with O.P. on cello) and the J.J. Johnson-Kai Winding-led Four Trombones (Debut) showed Mingus' ability to work with unique instrumentation to a colorful, artistically viable affect. However, Mingus' greatest coup of the year, however, was his inclusion in, and recording of, perhaps the definitive bebop document, Jazz at Massey Hall (OJC). Billed as the Quintet, Mingus, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, and Max Roach, jelled with astonishing results. The recording of a Toronto gig may be the greatest live jazz album, and is arguably the greatest assemblage of musical talent to take the same stage in the 20th Century. The record gave Debut a boost in credentials, and established Mingus as both an important archivist and instrumentalist. (Mingus, Roach and Powell also played on a second record culled from the concert, which isn't bad at all, but not at the same level as the Quintet.)

Mingus' next major project was an excellent and experimental solo effort, Jazz Composers' Workshop (Savoy). The title would prove prophetic - nearly every Mingus-led group after would be called the Jazz Workshop. The snappy "Purple Heart" and "Tea for Two" prove Mingus capable of crowd-pleasing. The totally improvised "Gregarian Chant" was an early attempt at the type of experiment Ornette Coleman would later define. "Eulogy for Rudy Williams" was one of the first Mingus tributes to a late fellow musician, and his staccato bass solo sounds like a string of teardrops. (The record has been reissued at times with an excellent 1955 date led by saxophonist Wally Cirillo.)

Jazzical Moods (aka The Jazz Experiments of Charles Mingus [Bethlehem]) is the next step, and is an under-appreciated gem in Mingus' creative output. Split between upbeat and prodding songs, a murky surrealism pervades the entire record. The spatial production (the record sounds as if it was recorded in St. Paul's Cathedral) and sinister underpinnings display the dualism in Mingus' music. An elegant melody will be interrupted by another, then another, until a dissonance masks the initial feeling. The title refers to Mingus' fusion of classical and jazz, emphasized by Jackson Wiley's cello as well as the counterpoint and a more classically oriented serialism. "Minor Intrusions" and "Stormy Weather" have a 1920s New York feel, with an uneasiness lurking under the surface.

Mingus spent much of 1955 as a sideman, doing good, if not revelatory, work on albums by Teddy Charles (Evolution [Prestige]), Thad Jones and John Dennis (both on The Complete Debut Recordings). Between labels, Miles Davis decided to go into the studio with Mingus to make a record for Debut. Unfortunately, most of the record they cut, Blue Moods (OJC), doesn't live up to the hype; the slow, cool aura isn't the equal of much of Miles' work in this arena. However, one great moment nearly redeems Blue Moods: a slow, haunting take on "Nature Boy." With Teddy Charles on vibes, and Elvin Jones working the brushes, Miles Davis coaxes an expressive, warm tone, and Mingus' rattling but restrained bass work takes the standard to a new level of expressiveness. "Nature Boy" reminds us of what we love about these two legends.

Mingus loudly staked out his territory in the jazz pantheon at a late 1955 date at the Bohemia in New York City. In the session, (divided into two releases, Mingus at the Bohemia and The Charles Mingus Quintet Plus Max Roach [both OJC], Mingus proves he had found his groove as a bandleader. With the anthemic "Haitian Fight Song" and "Work Song," Mingus' titles reflected a more overtly political bent. The avant garde "Percussion Discussion" (with Max Roach) and "All The Things You C-sharp" (a combination of "All the Things You Are" and Rachmaninov's "Prelude in C-Sharp Minor") display Mingus' dexterity with various strains of modern classical music in a jazz setting. The exhilarating "Jump Monk" opens the set - a perfect Mingus solo is followed by some of the sharpest ensemble playing of his career.

Pithecanthropus Erectus (Atlantic) would further amaze the jazz public. Rarely before had a jazz record contained four lengthy songs of mostly original material. Mingus was stretching the rules of the album format to fit his ever-expanding musical imagination. The title track, which told a musical story of the first man to walk, displayed Mingus' remarkable ability to shift dynamics, and the bursts of free-form blowing were a precursor to the music of Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane. On "A Foggy Day," Mingus took a new approach to the standard, emphasizing the atmosphere of a street scene with car horns and police whistles. Rarely before had a record of popular music contained such an expressive sense of narrative.

In case there was any doubt that Mingus was there to stay, The Clown (Atlantic) continues his progress as an album artist. While not quite the towering achievement of Pithecanthropus, The Clown contains some of Mingus' most powerful statements to date. The revamped "Haitian Fight Song" sounds better in a larger group setting, and the title track is an angry indictment of the music industry and its lack of empathy for performers. One of the outtakes from the album, the surging "Tonight at Noon," is one of the most memorable moments of Mingus career: the surging beat, propelled by Mingus' bassline, collides with powerful horn riffing for epic results, and the title betrays an eerie surrealistic bent.

The record also introduced Shafi Hadi, one of Mingus' most dependable and creative sax players, and Dannie Richmond, a former R&B saxophonist that Mingus converted to a drummer. Richmond would become the anchor of many of Mingus' greatest groups, and the pair displayed an awesome degree of musical intuition and personal camaraderie.

Mingus' good luck continued when Gunther Schuller, one of the acknowledged leaders of the "third stream," commissioned Mingus to work on a piece for the Brandeis Jazz Festival in mid-1957 (the recording, which features pieces by John Lewis and J.J. Johnson, among others, appears on The Birth of the Third Stream [Columbia/Legacy]). Mingus' "jazzical" concepts fit right into the "third stream," as he had been pursuing similar classical-jazz hybrids for years. The orchestra, which contained a number of past and present Mingus sidemen (John LaPorta, Teo Macero, Jimmy Knepper) play with a sympathetic, knowledgeable touch, exactly what the piece demands. The moody, ominous sound of the first half of "Revelations (First Movement)" gives way to spontaneous invention and back again. Much like "Half-Mast Inhibition," the combination of jazz improvisation with well-organized arrangements marked a compositional style Mingus would later take to the bank in the early 1960s, but at this point Mingus' orchestral pieces had been underrepresented in the marketplace. "Revelations" is Mingus' first hint of the greatness he'd achieve in the orchestral medium.

Those powerful moments are followed by Mingus Three (Roulette), one of Mingus' weakest piano trio albums. Despite solid personnel (Mingus and Richmond with pianist Hampton Hawes) and an interesting, rhythmic take on Gershwin's "Summertime," very little stands out. Nearly all of the tunes are given their definitive treatment elsewhere in the Mingus discography.

One of those tunes is "Dizzy Moods," the opening cut on Mingus' next masterpiece, New Tijuana Moods (RCA Bluebird), a record that brilliantly chronicled Mingus and Richmond's south-of-the-boarder excursion. Mingus plays his bass flamenco style on "Ysabel's Table Dance," accompanied by a flurry of castanets. "Los Mariachis (The Street Musicians)" paints a portrait of a group of musicians Mingus saw who followed tourists, trying to play the music they thought would get tips. The song itself shifts from a bluesy swagger to a jazzy take on Mexican folk. Richmond's drums pound and finesse with the experience of an old pro, and his status as Mingus' most important musical partner had already been solidified. The tourist-trap classic "Tijuana Gift Shop" and a take on "Flamingo" round out an album that Mingus once claimed was the greatest of his career.

Mellowing out a bit, Mingus' next geography lesson centered on bi-coastal musical identities nearly 40 years before rappers began doing the same. East Coasting (Bethlehem) joins Mingus with then up-and-coming pianist Bill Evans, who ads a note of restraint to the proceedings, sometimes eerily so. The up-tempo "East Coasting" shifts into the mellower "West Coast Ghost"; the former Californian had taken New York, but the multitude of styles within Mingus' reach was calmly reaffirmed. "Celia" and "Memories of You" are great ballads, and overall, East Coasting is solid and consistently listenable.

One thing didn't go right for Mingus in 1957: Debut Records essentially bowed out in the middle of the year, leaving some great music either unissued entirely or released outside the U.S. For example, Jimmy Knepper's outstanding solo date (Debut Rarities, Vol.3 [OJC]), which features several up-tempo, bopish cuts like "Latter Day Saint" and "The Masher," was only released in Denmark (where the trombonist's last name was allegedly a dirty word). The last recordings for the pioneering label took place in late 1957 or early 1958, and Mingus' combo sounds terrific on a tempo-shifting, bittersweet version of "Autumn in New York" and a Middle Eastern-sounding percussion and flute groove recorded, but not used, for fellow indie pioneer John Cassavetes' film Shadows. (These songs are available on Debut Rarities Vol. 4 [OJC].)

Perhaps because of his burgeoning status as a beatnik icon, Mingus' interests around this time turned to adding poetry to his music. He was not exactly a stranger to this realm, for "The Chill of Death" and "The Clown" both had narration and/or poetry. However, in late 1957 to early 1958, Mingus coordinated words to accompany the music that had always seemed descriptive enough. The results could be stunning: "Scenes in the City" (from A Modern Jazz Symposium of Music and Poetry [Bethlehem]) is almost like a beginner course in the jazz life, from the music (Mingus and company do their best impressions of everyone from Jimmy Blanton to Miles Davis), to the lonely, passionate life of a jazz musician. Upping the ante, Mingus next collaborated with a man who understood the balance between the past and present nearly as well as he: poet Langston Hughes. Weary Blues (Verve) is split down the middle: the first side featuring a small group ensemble lead by Leonard Feather, and the second side containing a Mingus combo, featuring Knepper and Hadi. Although some of the music wasn't written for Hughes' words, there's still a nice balance between the two. The 20-odd minutes these two legends are on record together are neat: you can hear a reading of the famous "Dream Deferred," or a string of classic Mingus (a speedy "Jump Monk," an early take on "Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting"). And on "Consider Me" and "Dream Montage," the words and music meet in a way few spoken word efforts have before or since.

Aside from recording some music for Shadows, Weary Blues would be Mingus' last recorded work in 1958. In the spring, Celia Mingus walked out on him. Mingus was on edge at this time, and tried to get some help. So he checked himself into Bellevue Hospital, which he soon discovered was not a good idea when he was not allowed to leave (Mingus' autobiography, <I>Beneath The Underdog</I> is at its best when it describes this strange period of his life). Mingus' contact with those who were in much worse shape than he made the bassist more committed to helping himself, and decided to approach his music with a new intensity.

Recorded a few weeks after the turn of the year, Jazz Portraits: Mingus in Wonderland (Blue Note) was the first shot fired by Mingus in what would be a revolutionary year for jazz, and a remarkably productive one for its greatest bassist. From the opening swagger of "Nostalgia in Times Square" to the game of hot potato played by John Handy and Booker Ervin on "No Private Income Blues," Mingus' music sounds remarkably assured and propulsive. Even one of Mingus' favorite standards, "I Can't Get Started," gets its best Jazz Workshop treatment on Wonderland - the slow, spatial take is one of Mingus' warmest recorded moments.

Blues and Roots (Atlantic), which has become many a Mingus fan's favorite, was next on the agenda. This time, Mingus set out to appropriate the fervor of his earliest musical influence, gospel, to the eclectic mix that was the Jazz Workshop aesthetic. It's largely successful: "Moanin'," which opens with the growl of Pepper Adams' baritone sax, builds on that riff with the type of counterpoint melodies that would continue to mark his big band records. "Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting" was the leadoff cut in Mingus' trilogy of gospel influenced, hand-clappin,' speaking-in-tongues numbers from 1959. "Wednesday Night" is loud enough, but not quite dark enough; the lo-fi sound of Mingus at Antibes (Atlantic) is better suited to the song.

Mingus' status as a major player in jazz had been solidified when he signed to Columbia, the label of Miles, Monk, Duke and Billie Holiday. He rewarded the company with his fullest and most accessible record to date. Mingus Ah Um (Columbia) contains a number of the legendary songs: the beautiful eulogy for Lester Young, "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat," the segregation protest "Fables of Faubus" (whose scathing, bitterly humorous vocal track was removed to avoid controversy), and "Better Git It in Your Soul," the greatest of Mingus' 1950's performances and the finest cut in the gospel trilogy. Elsewhere, Mingus the jazz historian puts together loving tributes to Charlie Parker, Jelly Roll Morton and Duke Ellington, and "Boogie Stop Shuffle" has regrettably never been used in a Hollywood car chase sequence. Mingus Ah Um is the best introduction to the Mingus aesthetic - it is the best example of his ability to play within the jazz tradition while exploding its boundaries.

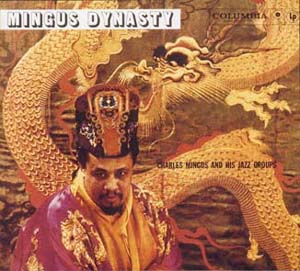

The follow-up, Mingus Dynasty (Columbia), doesn't have the breadth of Ah Um, but, with a superior recent reissue, its virtues are undeniable (an earlier release of the record shortened some versions of the songs). "Gunslinging Bird" (original title: "If Charlie Parker Was a Gunslinger, There'd Be A Lot Of Dead Copycats") is urgent and intense, while "Far Wells, Mill Valley" is a bittersweet tribute to an old friend. On "Mood Indigo" and "Things Ain't What They Used To Be," Mingus' fidelity with Ellington's music is not quite as playful and fresh as "Open Letter to Duke" on Mingus Ah Um, but the songs still sound great in the Jazz Workshop's capable hands. Overall, Dynasty lacks the breadth and punch of Ah Um, but is still great listening.

The 1950's would be the only decade in which Mingus would record consistently - he would take a hiatus in the 1960's, and by the end of the 1970's, he was stricken with Lou Gehrig's disease. However, Mingus came into his own as a composer and a gigantic talent, and the great recordings he made in the 1950's set a high standard he would continue to match throughout his great career. In his first full decade as a member of the jazz elite, Charles Mingus revolutionized the way jazz records were made, and pointed toward a bold future. Artists as diverse as Gang Starr, the Marsalis brothers and the Rolling Stones owe much to Mingus' 1950's work, which has transcended the genre of jazz, and is, quite simply, unique in the pantheon of American popular music.