The Ghost of Lester Bangs

by Ethan Stanislawski

(February 2009)

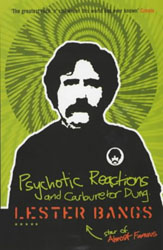

Lester Bangs, like many deceased luminaries in their respective fields of criticism, haunts everyone who, against all odds, decided they want to become a rock critic. I had mildly dabbled in pop music criticism before I first read Main Lines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste (quickly followed by Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung and a slew of internet scooping). Like many critics before me, I immediately tried to follow in Bangs' lead in my own writing. And like a playwright who's just discovered David Mamet, the results could be disastrous."Writers invariably come off as desperate and self-parodying when they try to imitate Lester," said John Morthland, editor of Main Lines. "Usually it's so unreadable you can't even call it derivative, and it sticks out like a sore thumb. Whether or not you recognize that it's a Lester imitation, you wonder how someone that bad ever got into print."

Yet, despite the impossibilities to imitating Lester, a slew of young writers will inevitably write in that style, and somehow succeed in getting away with it. With the Internet opening infinite doors, with no editors to ramble on about whatever you want, a new wave of rock writers have emerged in a trend that Robert Christgau once called "tyros opining for chump change." At countless music blogs across the country (some listed on Metacritic, some not), marginal music sites have emerged as some of the leading young voices of rock criticism. Most of these sites pay beer money at best, often they offer nothing financial at all. Without a doubt, the leader of these sites is Pitchfork Media, started in the Minneapolis basement of 19-year-old Ryan Schreiber in 1996. Many critics have called Pitchfork the biggest startup in rock criticism since Rolling Stone, for better or for worse.

Despite Pitchfork's remarkable name recognition and influence on the music scene, the site's level of trustworthiness has long been a subject of scrutiny and derision. The most recent case involved their hastily constructed review of Black Kids' debut LP Partie Traumatic. Originally a 0.0 with the line simply "Everyone makes mistakes," the review was later changed to a 3.3, with the body changed to a lolcat picture of two pugs saying "Sorry :-/"

Considering that Black Kids' overnight hype had been largely facilitated by Pitchfork's glowing review of their Wizard of Ahhhs EP, and considering that there was no substance to the review pointing to Partie Traumatic's flaws, the review started a considerable amount of controversy. The L.A. Times called it an "epic fail." Scott Plagenhoef, who was credited the review, blamed the change from 0.0 to 3.3 on a "regrettable computer error." Commenters on Drowned In Sound, MOG, and countless other music websites were outraged. And the music press world was reminded of what a loose cannon a Pitchfork review could be.

Pitchfork, of course, had a long, checkered history of such digs for snark. The Black Kids controversy is nothing to a site that has published such infamous reviews as Brent DiCrescenzo's factually challenged review of the Beastie Boys' To the 5 Boroughs, the slam at Travis Morrison (a 0.0 grade for his Travistan album) the obscene YouTube video that made up the review Jet's Shine On, or the "U.2" rating of British Sea Power's Do You Like Rock Music??? in order to make a parallel that few actually saw. Yet all the while, indie rock fans have been persistently drawn to the site, with public tastes very rarely deviating from the opinions of Pitchfork, and with the site's snarky style becoming ingrained in the generation's musical consciousness.

Snark of course, is nothing new to indie rock. You saw it in some of the earliest core texts by the likes of Richard Meltzer, Nick Tosches, and even a little bit in Lester Bangs. Yet, out of all the critics in the rock canon, Bangs is the one that most budding critics and fans turn to. He predicted punk years in advance, lived and died by his faith in rock and roll, and produced addictively readable, hilarious, and often shockingly abrasive commentary on the art. The famed quote by Greil Marcus, upon the publication of Main Lines read "What this book demands from a reader is a willingness to accept that the best writer in America could write almost nothing but record reviews."

Bangs was never one to eschew a smart putdown. His first published Rolling Stone review was a brutal de-clawing of the raw power of the MC5, a band he would grow to revere. Bangs became notorious for harshness to Grand Funk Railroad (who he despised) and Lou Reed (who he worshipped) and even his former colleagues and confidantes such as Patti Smith and Blondie. Bangs' attitude was accentuated by his Beat-influenced prose, often ignoring punctuation and going on for thousands of words. He was on speed many times when writing record reviews, and it showed. When you first read Bangs' review of, say, the Stooges' Fun House, or his mock review of Lou Reed's Metal Machine Music, Bangs' style is ostensibly what draws you in.

Yet, while that style may be the most obvious draw, what has kept Bangs relevant even today was something deeper about what he had to say. Bangs may have guarded his insights with self-described beatnik drivel, but it was his passion for rock and roll--and his assessment of its value to modern society–that made him the biggest icon in rock criticism

"The thing that people miss about Lester was that he was devoted to music, he really believed it was a force for life, and nothing less. There was an unfailing honesty in his writing that he felt he owed people" said Jim DeRogatis, Bangs' biographer. "One of the things that disturbs me is that people think it was all about the style, and far greater rock writers than the ones at Pitchfork thought this. I disagree to the core of my being."

"I can't overemphasize what a sponge he was for music." said Morthland. "His encyclopedic knowledge was sort of implicit in much that he wrote: when you read Lester you just knew that he knew what he was talking about. It made you trust him, and it's a big part of the reason his writing could be so honest."

Whether you can you draw a straight line between Bangs and Pitchfork, however, is up for interpretation. Morthland, for one, disagreed with my assessment of modern rock critics being sorry Lester Bangs imitators; he said the imitation was much more prominent in the 1970's, when there was less of an established tradition. "It's really common for rock critics of the last couple decades to say they were heavily influenced by Lester, tho' I'll be damned if I can see it in their writing."

DeRogatis, conversely, sees the imitators as inevitable. "There are a million bands copying Led Zeppelin, too. You can't blame Led Zeppelin for Kingdom Come."

Both, Morthland, and DeRogatis however acknowledged that that the ways rock criticism should be influenced by Bangs--his passion and conviction in music, and his overwhelming need to be true to himself--are lacking in many of today's critics. Both of them cite a rising trend in critics needing to feel like a part of the industry, as opposed to having an independent voice. According to Morthland, "I've always thought there were two reasons to become a rock writer. One, because you wanted to be a writer; and two, because you wanted to be in the music biz. You can invariably tell who's which simply by reading them."

DeRogatis, who was much more skeptical of the current state of rock criticism, argued that the Entertainment Weekly mode of rock criticism is beginning to dominate. "It drives me crazy at South by Southwest to be at lunch with a group of writers... and the things they say at lunch are very different than the things they say in print."

"Who are the top 4 or 5 Pitchfork writers?" DeRogatis challenged me. "You can't even name them. It's more about the brand than it is about developing good new voices."

For his part, Christgau, who responded by e-mail, could name his five favorite Pitchfork writers, and said he generally is a fan of the site's writing. He also noted "Imitation is always a mistake, but the closely related influence is not. I always tell young critics that there's no one good way to write well about music." Of course, Christgau also told me he almost never advises people to go into criticism.

When I set out to write this article, my emphasis was more on critics at Pitchfork and similar sites cheaply imitating Lester's style. In the end, however, the other side of that coin is what stood out to me: that all though some do critics emphasize Lester's style (how many do is debatable), it's Lester's passion, his insight, and his conviction in rock and roll that has deserted this generation. You could still find passion in fanzines era like Matter and Forced Exposure, which came after Bangs but before Pitchfork. The general disdain and cynicism from contemporary critics is something new.

Of course, with a crippled economy that's even more crippled when it comes to media and arts criticism especially, maybe that cynicism is to be expected. For all his skepticism and disdain for Pitchfork, DeRogatis told me that he can't really get too upset about the site. "At the end of the day, it's just some guy, sitting in his basement, making $50 to write 2500 words." And that's a good salary if you're writing about music today.

Also see the last interview with Lester, an unpublished article by Bangs about Brian Eno

and a reading of Bangs/Marcus and the Sex Pistols