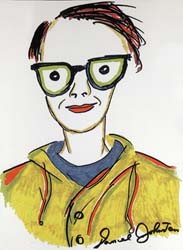

K. McCarty Does Daniel Johnston

Daniel Johnston's portrait of K. McCarty

By Kurt Wildermuth

(January 2002)

One day, let's say it was twenty years ago today, singer/songwriter/outsider artist Daniel Johnston was listening to the Beatles' "I Am the Walrus." Maybe you've heard it. It's the one with the surreal lyrics, the Lewis Carroll and Edgar Allan Poe references, and the insistent keyboard part inspired by an ambulance siren that kept John Lennon awake one night in 1967. "Goo goo goo joob." Johnston became obsessed, as certifiably disturbed people will, with the lyrics "Yellow matter custard / Dripping from a dead dog's eye." He kept repeating these lines to himself as he left his house--this was maybe in his adopted home of Austin, Texas, or maybe in his native West Virginia ("home of the na ve," as he puts it in his song "Wild West Virginia," where he pronounces it "[k]nave"). When he then happened upon a dead dog, its eye encrusted--encustard?--with yellow matter, he was shocked. "Dead dog's eyeball!" he said, and the phrase stuck in his brain. Whenever something eerily synchronistic happened after that, he'd say, "Dead dog's eyeball!" In fact, his friends started saying it, too.However many years later, K. McCarty's Dead Dog's Eyeball: The Songs of Daniel Johnston (Bar/None) was my favorite CD of 1994. It placed 36th on the Village Voice's Pazz and Jop critics' poll of 100 best recordings of that year. In its low-key, highly independent, psychedelic-folk-pop-rock way, it meant something to some people. Now it seems to be impossible to buy from your local chain store--if it was ever there--or to order from the label, which once, "as parents who think their child interminably golden," considered Dead Dog's Eyeball "one of our finest releases" (see http://www.bar-none.com). If true, this sad passing marks, more than anything, the flow of time and consumer demand. It doesn't necessarily damn Bar/None, of Hoboken, New Jersey, which has kept a lot of relatively obscure and offkilter music (The Scene Is Now, Tiny Lights, Health & Happiness Show, Professor and Maryann, et al.) available for a long time. Fun's fun, yes, but business's business. "A guitar's all right, John," as Lennon's Aunt Mimi used to tell him, "but you'll never earn your living by it."

John Lennon (with, I suppose, Paul McCartney) is to Daniel Johnston as Lou Reed is to Jonathan Richman. The man is father to the child, if you will. In short, like a few other people, though perhaps more than most, Daniel Johnston loves the Beatles. He once reportedly drew up a ten-favorite-albums list that included nine Beatles records and Glass Eye's Bent by Nature (1988, also Bar/None--and either, as of this writing, out of print or out of stock). Glass Eye (1984-1993), from Austin, was a weird hybrid of folk, funk, punk, indie, and hard rock, sort of like the Minutemen crossed with Thin Lizzy crossed with the Au Pairs, and K(athy) McCarty--in addition to playing the Anarchist's Daughter in Richard Linklater's first feature film, Slacker (1991), set in Austin--was their singer/songwriter/guitarist. So you see the conspiracy, the sychronicity, or at least the cross-references, working overtime.

Daniel Johnston's been institutionalized, he's been on a major label (Atlantic released 1994's Fun, produced by the Butthole Surfers' Paul Leary), he's sold his highly amateurish artwork, but he's still best known for a series of extremely lo-fi cassettes he recorded and sold on his own, highlights of which were released on CD's by Homestead--all of this in the early to mid '80's. Or maybe, to the world at large, he's best known in the form of a much-photographed T-shirt singer/songwriter/guitarist Kurt Cobain--speaking of Beatles fans--wore toward the end, a promotional item for Daniel's Hi, How Are You CD (1983).

"I just knew he was a genius," K. McCarty says in Gina Arnorld's (sic) essay inside the cover of Dead Dog's Eyeball, and Kurt Cobain might have agreed, and the people at Homestead and Atlantic and Paul Leary must have agreed, and fifty million fans can't be wrong, but some of us didn't hear it. We couldn't listen past the surface noise, the cruddy sound, the cruddier instrumentation, the whiny and offkey singing, the infantilism: "I am a baby (in my universe)," he explains in one song, and no kidding. Were we, new-wavers turned nine-to-fivers, missing out, or were the hipsters deluding themselves into seeing something imperial in Johnston's big, crazy nakedness?

That's why K. McCarty's work was so welcome and so valuable. It rendered Daniel Johnston's music listenable for the rest of us, it made his songs available to people who wouldn't have gotten it--the joke, the genius--who maybe couldn't enter the microcosm, the alternative universe, in which this music was formed, forged (hammered out and, to an extent, counterfeited). Yo La Tengo's cover of "Speeding Motorcycle" (on 1990's Fakebook, Bar/None) had been a way in, but only part of the way. Dead Dog's Eyeball was all Daniel Johnston, all the time, a brand-new baby (in his universe). It made the case for Johnston as a legitimate songwriter rather than a novelty act or freak show to be peeped at, and it did so without robbing the music of its strangeness, the way David Cronenberg made idiosyncratic yet faithful movies out of such unfilmmable novels as Naked Lunch and Crash. McCarty and coproducer/coperformer Brian Beattie, also of Glass Eye, provided a diverse set of musical backdrops, from heavy metal to noise-rock to lounge jazz to gospel to running water (literally, from a University of Texas bathroom, for an otherwise a capella number called "Running Water"). "Intro," opening the proceedings and later repeated without a title, is a jaunty bit of solo piano that quotes "Three Blind Mice" (which, come to think of it, John Lennon borrowed the tune of for "My Mummy's Dead," the brief "outro" on his primal-therapy masterpiece, 1970's John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band--the plot thickens!). Suggesting old-time dancehalls and vaudeville houses, it sets the theatrical scene, the sense of guises being assumed within an aural proscenium. McCarty makes like a dummy speaking for the ventriloquist, fleshes out Johnston's script, inhabits his characters (female and male) and turns his songs from apparently confessional rants into a series of personas. She gives, we might say, form to his content. "People say we're an unlikely couple / but I'm seeing double... of you" goes "Living Life" (which Richard Linklater used at the end of his charming, talky, lyrical, romantic, but otherwise uncategorizable third movie, Before Sunrise [1995]). "People say we're an unlikely couple / Doris Day and Mott the Hopple." It's supposed to be Hoople, of course (as in "All the Young Dudes," mate), but McCarty mispronounces it as Johnston does, to maintain what the liner notes call "the integrity of the song" and the skew of its vision. Diving headlong into this simplest of Buddy Holly-esque acoustic ballads, McCarty conveys the sense of a heartful someone struggling against mighty forces and finding in music a way to keep going, however provisionally. That is, she enacts, in miniature, the Daniel Johnston story. "Ah, hope for the hopeless / I'm learning to cope / With the emotionless mediocracy / Of day-to-day living." The sense of life implied here, life as screwball adventure, life as arena for serendipitous discovery, life as constant invention, life as happy collision of incongruities, life as a bunch of kids with crayons and vivid imaginations, informs Dead Dog's Eyeball the way, say, feta cheese informs a Greek salad.

When he needs inspiration (this according to McCarty in a New York City radio interview all those years ago), Johnston often opens the Beatles' songbook, starts playing, and simply turns borrowed chords into his own song. "Hey Jude, come on Joe," begins "Hey Joe," "don't make a sad song / sadder than it already is." The musical setting here of course echoes the reference, but not exclusively. No one thing ever happens at any time in this echo chamber: "Hey Jack, get back / get yourself together / come on... Hey Sid, no matter what you did... Hey George," and so on. Such optimism, despite life's overwhelmingly negative odds, is pretty much the blood on and coursing through these tracks. But mixed in the flow are some hard, sophisticated truths, lines shooting out like darts, as in "Grievances": "Well, it just goes to show ya / That we're all on our own / Scrounging for our own share of good luck / Stab your brother in the back / And pick up your paycheck." While Johnston may be out there (in both senses, in fact out of his senses), he's also in here with us, inside the system and its workings.

"Try to point my finger / But the wind keeps turning me around in circles" is how one of the CD's standout tracks, the ecstatic "Walking the Cow," puts it. "Lucky stars are in your eyes / I am walking the cow." It's a paean to survival through shape-shifting, through poetry in motion. As John Cale-like hammered drums and piano lead to Philip Glass-like sawed strings and electric guitar, only the hardest hearts would remain unmoved by the affirmation in McCarty's lilting alto.

Equally beautiful, perhaps (to go parenthetically out on a limb here) the most breathtaking performance of her career so far, is "Worried Shoes." It's "Strawberry Fields Forever" meets "Nowhere Man" meets "Try a Little Tenderness" meets "Whiter Shade of Pale," and it appears on Sorry Entertainer (1995, Bar/None-- temporarily out of stock), Kathy (no longer just K.) McCarty's odd postscript to Dead Dog's Eyeball. She reportedly--hope springs eternal--shot her own video for the title track of this EP-CD (produced by and again co-performed with Brian Beattie), which contains two slightly remixed versions of songs from Dead Dog's Eyeball, one so-called live version that sounds live in the studio, a scorching Glass Eye track with no date, and three more Daniel Johnston covers. Rocking harder than most of the full-length, these seven tracks are just as emotionally effusive and nearly as revelatory. They're also, as far as I know, McCarty's latest recordings. If this sounds like your kind of thing, be on the lookout in used bins, on ebay, wherever miracles happen.

While I'd been planning this article for months, I started writing it on Friday, November 2. To prepare, I listened to Dead Dog's Eyeball and two Glass Eye albums, the aforementioned Bent by Nature and Hello Young Lovers (1993, Bar/None, temporarily out of stock). On Sunday, November 4, I set off for a benefit record sale, planning to keep my eyes peeled for a copy of Sorry Entertainer, which, believe it or not, I'd never heard because I'd always figured it would be a letdown. On the way, I stopped at a thrift store one block south and found a copy of the EP in the second or third bin. Dead dog's eyeball! At the sale, meanwhile, I found a copy of Glass Eye's first LP, Huge (1985, Wrestler Records, OOP for sure), the first one I've ever seen. Dead dog's eyeball! At home that night, I played those purchases and one other, the Meat Purveyors' More Songs about Buildings and Cows (1999, Bloodshot). It's their second CD, and its title pays homage to the Talking Heads' second album, More Songs about Buildings and Food (1978, Sire). On their first CD, Sweet in the Pants (1997, Bloodshot), this bluegrass-country-folk-pop-rock band from Chicago, Illinois, cover Glass Eye's "Dempsey Nash" (also known, mysteriously, as "Dimsey Naish"), and guess what? Like K(athy) McCarty, only differently, this time they cover Daniel Johnston's "Museum of Love." All together now: Dead dog's eyeball!

2005 update: The good people at Bar/None Records have just reissued Dead Dog's Eyeball with bonus material and video footage.