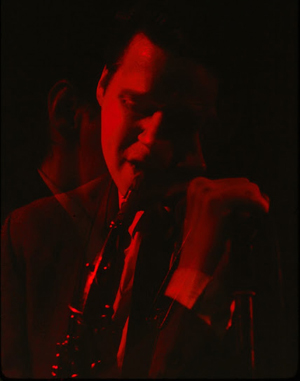

JAMES CHANCE

photo by Jeff Ellis

FAVORITE NOIR FILMS II

compiled via Tim Broun

(August 2013)

Here is part two of James Chance's top ten film noir favorites. We ran the first part a few months ago, and that can be seen here. Since then James has completed a successful European tour, played several New York City dates, and also made his first ever appearance in South America, in Sao Paolo, Brazil, at the Virada Cultural 2013 festival. On July 6 he appeared with the current line up of the Contortions at Le Poisson Rouge in New York.

On the 2010 release, The Fix Is In, James Chance very successfully puts his own spin on jazz and R&B, in a very similar way he usually has fusing funk and punk - best known via his groundbreaking releases with The Contortions. After recently starting to work with James - helping him out with an online presence (see his website here, and his Facebook page here) - I came to find out just how knowledgeable he is about an era of film and literature that his music has always hinted at. The era being noir, beat, mystery, dimestore, detective, all of the above, whatever you'd like to call it. I asked James to put together a list of his top 10 film noir movies, and here is part one of the result. James' latest album, Incorrigible, is available now, and he begins a European tour on Valentine's Day. See all upcoming shows on his website here.

Big thanks to James for putting this together!

#6 The Locket (1946)

My noir top ten wouldn't be complete without one of Robert Mitchum's films as he is the actor who most thoroughly typifies film noir to me - though to Mitchum himself the very idea of film noir seems to have been something of a joke. He once claimed that the reason his RKO films were so dark was because the studio had no budget for light bulbs. If I was being totally "objective" the Mitchum flick I would have to pick would be Out of the Past, but that one has been written about so much that I would prefer to take a pass. Instead I'm going to pick one of Mitchum's early RKO vehicles, The Locket, even though his role here is atypical - an ostentatiously uncompromising painter who "reeks of integrity" in the immortal words of Sidney Falco, going out of his way to insult anyone he considers to belong to the "parasitic rich."

The Locket is deservedly famous for its intricate flashbacks within flashbacks structure, plus voiceovers by both of the male leads: Mitchum's artist and the rather stuffy Brit Brian Aherne as a self-satisfied, educated fool type psychiatrist. But the film revolves around Laraine Day, an actress who spent most of her career trapped in ingenue roles, as Nancy Blair, a most unusual femme fatale, with none of the usual slinky trappings, who nonetheless drives the psychiatrist to insanity and the painter to a most artistic high dive from the shrink's skyscraper office window. She's an utterly conventional perky Junior League type on the surface, but in reality a pathological liar and kleptomaniac, obsessed with pilfering the jewelry of the very aristocratic women whose social class she aspires to (it's rather hilarious that Mitchum's painter character, who professes such contempt for the rich, is outraged when Nancy expropriates their baubles). Eventually, Nancy resorts to the murder of her employer, who's also Mitchum's patron, to cover up the theft of his wife's necklace. She then allows an innocent servant to be executed in her place & emotionally blackmails Mitchum into going along with her mendacious cover-up, triggering his plunge into oblivion.

Freudianism was at the height of its influence at the time The Locket was made, and the film explains Nancy's personality disorder as the product of a childhood trauma when she was terrorized by a wealthy matron, her mother's employer, who falsely accuses her of stealing the title trinket. However it's refreshing that the psychiatrist in the film is shown to have no insight at all - Robert Mitchum scornfully tells him "You're no psychiatrist. You don't know truth from lies. You're just a lovesick quack." A welcome contrast from the near god like powers to probe the mind (with the aid of their trusty "truth serum") psychoanalysts possess in many other films of the period.

I've personally suffered the misfortune of prolonged exposure to a woman of Nancy Blair's type and can assure you that the character's portrayal is extremely true to life, especially her triumphant and total denial when Brian Aherne, now married to her after her artist beau's suicide, discovers her stash of stolen sparklers in the ruins of their apartment after it's blasted in the London Blitz and brandishes them in her face - with an expression of utter blankness and innocence she asks "What's that you've got? Did you just find it? Don't tell me there's more of them?"

In the end, Nancy hooks another hapless male, and a rich one at that, and in an outrageous, Cornell Woolrich-like coicidence, he turns out to be the son of the woman who tormented her over the locket, and who now gives the locket to Nancy on her wedding day as a family heirloom. Then it's time for the ceremony, as one of the insipid bridesmaids urges Nancy to “look serious- think of something tragic." So Nancy does just that - in an inspired use of montage by director John Brahm, she sees disturbing scenes from her life unreel like a movie beneath her feet as she descends an ornate staircase. As she reaches the wedding party at the bottom, a psychotic break occurs- her personality splinters and then collapses to a near catatonic shell.

Although this makes a terrific denouement as well as satisfies the audience's (and the Hollywood Production Code's) need to see the character punished, I find it to be psychologically improbable. In real life, especially with wealth to cushion her. a Nancy Blair would be far more likely to go on indefinitely dealing out misery to everyone around her.

The Locket's director, John Brahm, is perhaps the most underappreciated of the classic noir directors. His unique period thriller about a demented composer, Hangover Square, has been described in Film Noir: The Encyclopedia, as "a nonstop compendium of noir imagery." Brahm spent the second half of his career mostly working in television, where he transplanted the noir sensibility to the smaller screen and the fantasy/sci-fi genre - he directed 12 episodes of The Twilight Zone and two of The Outer Limits as well as many episodes of such mystery/detective shows as Alfred Hitchcock, Naked City, Johnny Stacatto, M Squad and Thriller.

I was so impressed with how well written the character of Nancy Blair was that I did some research on The Locket's credited screenwriter, Sheridan Gibney. I didn't discover much about the origins of the character, but I did discover a tale of the Hollywood blacklist that's as dark as the film itself. Sheridan Gibney was a first rank screenwriter with an Oscar to his credit - he wrote the adaptation of the proto-noir I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang as well as such mainstream fare as Once Upon a Honeymoon, Green Pastures, and Letter of Introduction. The same year The Locket was released, 1947, mogul Jack Warner (of Warner Bros.) named Gibney before the House Unamerican Activities Committee as a member of a group of authors who "tried to inject Communist ideas" into their scripts. The characterization of Gibney as a Communist was entirely false and Warner later retracted it, but it was too late. The damage was irreversible, and Gibney's Hollywood career collapsed, never to recover.

But that's only the beginning. It turns out that Sheridan Gibney only adapted an earlier script of The Locket by another blacklisted writer, Norma Barzman, who in turn had adapted it from her own novel, What Nancy Wanted. She and her author husband, Ben Barzman, fled Hollywood and America into European exile about the time The Locket was released. It would appear that RKO, eager to disassociate themselves from a Commie writer, hired Gibney to do a hasty rewrite only to have him suffer the same fate. Even now in the film noir reference books, Norma Barzman is uncredited for The Locket although she obviously created the story.

Moguls like Jack Warner collaborated with the blacklisters not out of any political conviction - they'd been knowingly employing Communist talent for many years - but because the right wing's assault on radicals and liberals alike threatened their profits. If Warner and his fellow executives had defended their employees they might have stopped the blacklisters in their tracks. Instead for the sake of expediency, and probably because the threat of the blacklist maximized their own control, the Hollywood establishment went along with what they knew to be a classic Big Lie - that leftist creative talent such as Norma and Ben Barzman were such a threat to America that they deserved to be ostracized and deprived of their livelihood (the same fate suffered by creative artists who refused to follow the Social Realist party line in Stalin's Russia). It's appropriate that The Locket was the last Hollywood film of both Sheridan Gibney and Norma Barzman, for their careers were inexorably crushed by the perpetrators of the blacklist in the same way as Nancy Blairs victims were consumed in the vortex of her pathological but extremely convincing lies.

#7 Nobody Lives Forever (1946)

Nobody Lives Forever (1946) was directed by Jean Negulesco and scripted (from his novel I Wasn't Born Yesterday) by W.R.Burnett, two of the most underrated of the creative minds behind classic film noir.

Today W.R.Burnett is never included (or analysed endlessly) in the exalted company of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler or James M. Cain, yet he was as influential as any of these sometimes overly praised authors on the genre now known as ‘noir’ as well as virtually singlehandedly creating its precursor, the 1930's gangster film/novel with Little Caesar and the original Scarface. Burnett excelled at creating characters (complete with authentically tough dialogue) who were out and out professional criminals, as opposed to ex-cop shamuses, WWII vets with a few screws loose, infatuated insurance salesmen etc. An unpublished novelist at age 28, Burnett threw up his civil service job and headed to Chicago in 1927, just in time for the climax of the Capone era - in fact he was reportedly one of the first on the scene of the St. Valentine's Day Massacre. He found a job as night clerk at a shady hotel, which gave him firsthand exposure to all manner of bent characters.

Burnett gave even his heisters and hooligans like Roy Earle in High Sierra, or Dix Handley in The Asphalt Jungle, a yearning to get out of The Life and a personal code of honor. According to his IMDb bio, such characters "typically get one last shot at salvation but the oppressive system closes in and denies them redemption." To me, this speaks to the essence of the noir worldview - when a man has spent a lifetime on the dark side, his one selfless act, far from redeeming him, often leads directly to his undoing. Nick Blake (John Garfield), the con man (anti)hero of Nobody Lives Forever, discovers this inexorable reality, although he manages to sidestep the final catastrophe, perhaps because although he's a grifter, he's not a man of violence.

Born in 1900 in Romania, Jean Negulesco must have been an adventurous and determined youth. He absconded from his home at the age of 12 to Paris, washing dishes to finance his dream of becoming a painter. By 1927 he had fought in World War I , added stage decoration to his repertoire and reached New York. He then spent years traveling across the U.S. to Los Angeles, painting portraits to survive. Beginning as a sketch artist at Paramount in 1932, he worked at nearly every behind the cameras creative job in pictures before finally being given the chance by Warner Bros. to direct Eric Ambler's The Mask of Dimitrios in 1944 (along the way Negulesco suffered the indignity of being fired as the director of The Maltese Falcon and replaced by John Huston).

A tale of an international scoundrel's progress through the capitals of pre-WWII Europe, The Mask of Dimitrios established the parameters of Negulesco's noir style - a sophisticated approach with a minimum of violence and tough guy cliches and a maximum of mood, character, and sharply observed milieu. In the case of Nobody Lives Forever, he turned to the world of the big (as well as small time) con.

The big con is an aspect of the underworld rarely explored in classic film noir. Later films on the subject, both popular entertainments like The Sting and neo-noirs such as David Mamet's House of Games, tend to focus on elaborate con scenarios played against greedy, unpleasant marks whom the audience feels deserve to be fleeced. The con in Nobody Lives Forever, however, couldn't be more elementary - "That's an original idea, taking a widow!" Nick Blake snorts when he is first steered to it. It's the well worn "con man/woman falls in love with victim" plot, oft used in 1930's comedies like The Lady Eve, here made more credible by the performances of the principals John Garfield as Nick Blake and Geraldine Fitzgerald as the unworldly wealthy widow he intends to take. Garfield was much more than just a tough guy and its mostly his charm that's evident here, although when called for he reveals the steel just beneath it. Geraldine Fitzgerald's refinement may seem out of place in the noir genre (although she very effectively played an obsessed manipulator in another of Jean Negulesco's noirs, Three Strangers), but she does bring warmth and dignity to a role that could easily have slipped into caricature. But what really makes this film special to me is the rogue's gallery of Warner's contract players and the lovingly detailed depiction of both the high end and, especially, the lower depths of the grifter's milieu.

The film even works in a "returned GI" angle by starting the action with Nick Blake's return to New York after having been wounded in combat in Europe. He's left his posh apartment and $50-G bankroll in the care of his sultry singer girlfriend Toni (Faye Emerson) but discovers that she's installed a pseudo sophisticated gigolo type in his place. This pair have opened a ritzy nightclub with Nick's dough but refuse to cut him in on the profits. Nick and his sidekick, Al Doyle (George Tobias), a big cheerfully cynical lug, corner the gigolo alone in his office while Toni is onstage singing "for a bunch of Park Avenue drunks" and intimidate him into "kicking in" the missing 50-G's. Feeling understandably disenchanted with the NY scene, Nick, along with his reluctant sidekick (who's in a hurry to get down to the action), takes a train to Los Angeles and rents a beach house, planning on nothing but a long rest.

Once in L.A., Nick looks up an old pal, Pop Gruber (Walter Brennan), a broken down ex-bigtimer whose fortunes have descended to a scam selling drunks a look through a telescope in a park for a dime while he picks their pockets. Blake is also spotted by Doc Ganson (George Couloris), another ex-"top guy" with a barely concealed violent streak who's been reduced to working with a couple of rather pathetic strong arm types, Shake and Windy. Doc has lost the wherewithal to maintain his "front" and his confidence has curdled into "jumpiness," bitterness and envy of his colleagues who are in the money - in fact the younger, more handsome and, to him, effortlessly successful Nick Blake has long been his "pet hate." As David Maurer writes in his authoritative 1940 study The Big Con (which sometimes seems to have been written about the characters in this movie). “A confidence man must have plenty of ego. Once he loses his self-confidence, he is a failure; without the knowledge that he can trim a mark, he is incapable of trimming one... He sustains that confidence at all costs - or degenerates to some other form of the grift where he can function more successfully. But he cannot fool his associates long... Professional jealousy is, however, rife. There is a widespread tendency to "knock" other con men; real or fancied wrongs lead to strong and bitter personal criticism. It is not difficult to find a con man who classifies half the men he has worked with as ‘tear-off rats.’"

Doc Ganson is obsessed with a potential score he's stumbled upon, Gladys Halvorsen (Geraldine Fitzgerald), a recent widow from the Midwest reputed to be worth several million dollars. As much as he despises him, Doc realizes he needs Nick to make the play for the widow, so he recruits Pops Gruber, who reluctantly agrees to make the pitch to Nick, although he can't stand Doc. Nick reacts with scorn to the idea, but Pops and Al Doyle use reverse psychology on him. Doyle insinuates that Nick isn't up to the challenge: "A guy can lose his touch awful quick in this racket. One bad slip and you're cooked." To which Nick, now hooked, retorts: "I don't make slips!"

Blake and Doyle move into the widow's swank hotel, the Marwood Arms, posing as up-and-comer in the marine salvage business complete with some phony blueprints of ocean going tugs. His front is paper thin- he doesn't even have, as big time con men routinely did at this time, a political fixer on hand in case the play goes bad. However the widow, Gladys, is strongly attracted to Nick, and it soon looks like the score is in the bag. But Nick has little control over the slips of others or over blind accidents, and a lethal combination of the two is what queers the pitch irrevocably. Doc Ganson gets so bent out of shape about Blake "not bearing down hard enough on the take" and romancing Gladys instead that he "cracks out of turn" and goes in person to the Marwood Arms to confront Nick. But even in his best suit, Doc gives off an unmistakable aura of seediness and barely controlled aggression- he "ranks the joint," stumbling, as he exits an elevator, into Glady's financial advisor, who until now has been so blissfully intent on his golf game that he's been oblivious to Blake's con. Then a bellboy, who happens to be an ex-jockey from Miami, tells the mark that he knew Doc there as an inveterate race fixer, and that he was at the hotel to see Nick, prompting the advisor to put in a call to the L.A. district attorney. They set a trap for Nick by telling him to come and pick up a check for stock in his phony company.

But Nick Blake's "grift sense" is too acute - Doc's bonehead play convinces him that "the deal has gone haywire" and he turns down the proffered check, telling the mark that he "can no longer recommend the investment." "That's what comes from getting mixed up with small time chiselers - always hungry, always scared," Nick laments. Nick even decides to pay off Doc and his boys out of his own pocket to save the widow from Doc's threats to "take over the play myself- and I play rough."

Nick's attempted unselfishness blows up in his face when his New York doll Toni shows up- her nightclub has folded and she's looking to glom onto whatever Nick has going. She takes one look at Gladys and observes, "She's not hard to take, and she's batty about Nick, I can tell," then jumps to the understandable conclusion that Nick plans to marry the widow, cut all his partners out, and end up with all her money (actually he just wants to wash his hands of the whole mess and go back to New York). When Toni whispers these glad tidings into Doc's ear, he "blows the top off," shanghaiing the hapless Gladys to a shack on the end of a deserted pier on the Pacific where he and his clueless associates plan to hold her for ransom. Nick and his pals are forced to rescue her; Doc gets his with a .45, but so does old Pops Gruber, whose last words are the title phrase, "Nobody Lives Forever." As Nick Blake said about Pops earlier in the film, "That's conning on the square."

#8 Odds Against Tomorrow (1959)

Despite their lacerating portrayal of American society in many other ways, the makers of film noir were as lily white as the rest of Hollywood when it came to portraying African Americans. With the exception of some boxing films, such as Body and Soul, with the great black actor Canada Lee as John Garfield's trainer, blacks in classic film noir were usually relegated to menial types or occasional musical numbers. It took what many consider the last great film noir at the very end of the classic cycle in 1959 to remedy this glaring deficiency - Robert Wise's Odds Against Tomorrow.

This heist film's entire plot revolves around an interracial team of bank robbers and the inability of the racist white strong-arm man (Robert Ryan) to trust a black man (Harry Belafonte) who is necessary for the plan to work, causing the getaway to fall apart at the crucial moment and the death of both men. On top of this, Odds Against Tomorrow also features perhaps the first blatantly gay character since the pre-Code era's mincing pansies, a "pretty boy" mob enforcer named Coco who puts the moves on Harry Belafonte, in the screen debut of character actor Richard Bright, best known as hitman Al Neri in the Godfather trilogy. It's just a throwaway line, easily missed, but even a hint of interracial gay sex was quite startling in 1959.

The film was released by United Artists but actually made by Belafonte's production company (a major studio would never have taken such chances in 1959), and the part of Johnny Ingram seems to have been tailored for him - what in William McGivern's original novel was an uneducated black itinerant gambler with rather an inferiority complex toward whites becomes a much prouder and more sophisticated jazzman - a vibes player/singer - with a raging gambling addiction. He describes himself as "a bone picker in a four man graveyard." Ingram's spiraling gambling debt to an old fashioned Mafia don (Will Kuluva), who describes him as "a very entertaining boy (who) knows his place," makes Ingram vulnerable to being pressured into participating in a robbery being put together by an ex-detective who's been canned for corruption (Ed Begley) and is obsessed with getting back at the police department for making him into a "patsy." Belafonte intuits that the heist- of a bank in a small upstate New York town that Begley insists "you could take with a water pistol" - is like facing "the firing squad- that's for junkies and joyboys." But he's been backed into a corner by his supposed friend Begley,who without Belafonte’s knowledge, convinces the gangster to demand the entire $7000 debt immediately (thus making a patsy out of Belafonte just as the police department did to him).

It's the same corner Belafonte feels he's been painted into all his life by white society. As he tells his ex-wife, a liberal Negro integrationist, with the bitter wisdom of the street life she can't comprehend, "It's their world and we're just living in it," an observation that to me is just as valid now over fifty years later, no matter how many Afro Americans now enjoy a bourgeois suburban lifestyle or even the presidency.

Belafonte's performance here is one of the hippest portrayals ever of a black jazz musician (much better than Sidney Poitier's overly earnest tenor sax player in Paris Blues, made about the same time). Certain details, such as his English sports car and Continental suits, seem to owe their inspiration to Miles Davis (though you wonder why he couldn't sell the car to pay his gambling debt). I'm a connoisseur of nightclub scenes in movies, and the extended one here is one of the finest, beginning with Belafonte singing a blues with the closing line "I can't take that jungle outside my back door" as the hoods enter and take a table. Coco delivers the message that his boss Bacco wants to see him plus his little pickup line, then the scene shifts to the clubowner's office where Belafonte's confrontation with the boss ends in irrevocable disaster after he pulls a gun in response to Bacco's threats. The wild finish features a crazy drunk Belafonte howling offkey as blues singer Mae Barnes does a number called "All Men Are Evil" and as a finale slamming out atonal chords on his vibes- an expression of his rage and frustration, not a precursor of free jazz.

Making Belafonte a vibist, as well as the singer he was in real life, probably had something to do with composer John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet, whose score heavily features his bandmate, the incomparable vibist Milt Jackson as well as the white pianist Bill Evans and guitarist Jim Hall. Lewis's score eschews the usual brassy big band cliches, instead achieving a kind of floating, haunted effect, especially in the gorgeously photographed scenes where the heistmen are separately marking time on the edge of the town by the Hudson River, pensively counting down the minutes until they must go into action.

It has recently been revealed that Odds Against Tomorrow was actually scripted, using a young black friend of Belafonte's as a front, by writer/director Abe Polonsky, one of the most celebrated victims of the Hollywood blacklist, along with frequent Robert Wise collaborator Nelson Gidding who also scripted I Want To Live! I was surprised to discover that the screenwriters omitted the entire second half of William McGivern's original novel, in which the white racist and black characters escape the robbery, wounded and without the loot, and are forced to take refuge on an isolated farm inhabited by a demented elderly couple. A new ending was substituted which is rather obviously cribbed from White Heat, in which the two, trying to escape their pursuers, climb to the top of a huge gasoline tank which improbably explodes when they begin shooting at each other for no reason except their mutual hatred. To me this is the only weak part of the film, since it hits you over the head with the message so obviously.

William McGivern, like W.R. Burnett, is a now neglected writer who made a huge contribution to film noir. In the late 1940's, McGivern was a police reporter on several Philadelphia newspapers and his experiences there informed novels like The Big Heat, Rogue Cop, and Shield for Murder (all later filmed) which typically revolve around corrupt or overzealous police detectives caught within the nexus of interconnected big city political machines and crime syndicates. Odds Against Tomorrow contains such a character, but the exploration of racial hatred gives it a whole other dimension. Superb as Harry Belafonte's performance in Odds Against Tomorrow is, it's surpassed by Robert Ryan's portrayal of his nemesis - a white racist named Earl Slater whose background can be ironically summed up by the racial epithet "white trash." Ryan, in real life a liberal and a gentleman, had an intuitive genius for portraying outsiders of all kinds and had twice before played murderous bigots - an anti-Semite in Crossfire and a WW2 Jap-hater in Bad Day at Black Rock.

But those earlier roles are one dimensional compared to Earl Slater - a man who is ultimately unable to communicate except in terms of violence and experiences his life and relationships to others as a form of imprisonment. He's suffered literal imprisonment as a result of an inadvertent manslaughter during a bar fight. The original novel fills in some more of Slater's backstory: "I grew up on three dirt acres. We lived like niggers... right beside 'em... eating the same stinking food and wearing the same rotten clothes. And my old man tied me up and beat me like a dog for playing with them as a kid...I lied about my age to get into the army. I would have lied to get into hell. Anything was better than that shack."

It could be argued that such a character panders to the comforting liberal belief that racism originates in the lower depths as opposed to permeating the entire society. But Earl Slater is so powerfully drawn that one ignores such considerations. Such a man would cling to his conviction of superiority over blacks as his only certainty.

Shelley Winters, in a rare completely sympathetic role, plays Slater's girlfriend Lori, a working girl who excels at her job as manager of a lunch counter in a way that Slater is incapable of. She's perfectly willing to support him and committed to the difficult task of loving him. The novel makes it crystal clear that he experiences this relationship as an imprisonment as well, even though he genuinely loves her as much as he is capable of: "He knew she was just using her body as part of the locks and bars of her quilted little prison... Forget everything and sink back into oblivion with her- that's all she wanted. But he couldn't work up any anger either; he understood her needs and there was pity mixed with his exasperation."

Gloria Grahame, in one of her last roles after ill-advised cosmetic surgery had somewhat marred her face, has a cameo as an upstairs neighbor who, titillated by the violence in Robert Ryan's character, uses a request for him to babysit her child as an excuse to seduce him. In the book, unlike the film, Grahame's attempt fails, but her demand that Ryan be her babysitter is the final humiliation that decides him to take part in the robbery: "He was so angry his voice broke like that of a child trying not to cry...'You want me to smile at that little whore upstairs and change her kid's diapers?'... His voice rose in a fury. Is that it, Lori? Do you want to beat me into nothing? Nothing at all?'"

From what depths in his own life was Robert Ryan able to so thoroughly humanize such a character as to make one deeply identify with him as he throws away whatever chances he has left? Perhaps he perceived that for all his repugnant qualities, Earl Slater has a terrible honesty that he is incapable of suppressing, and that while perhaps redeems him, also contributes much to his downfall. Consider this exchange between Ryan and Gloria Grahame:

Grahame: How did it feel to kill that man?

Ryan: Do you want me to make your flesh creep? It scared me but I enjoyed it... I could have killed him all over again. He dared me like you are now.

On the back cover of my paperback edition of the novel Odds Against Tomorrow the two main characters are aptly described as "two losers about to play a sucker bet with their lives." But they are beautiful losers, and maybe that phrase captures the attraction, and dangers, of the noir worldview.

#9 Scarlet Street (1945)

What would film noir be without its marvelous, idiosyncratic villains, and the one easily at the top of my list would have to be the one and only Dan Duryea. I wouldn't exactly call Duryea a "heavy" like Raymond Burr or Ted De Corsia - in fact, there's a definite lightness and humor in his approach to villainous roles. Duryea was most famous in his own time for slapping women around - something I get the impression many of the men in his audience not-so-secretly approved of. Yet the female fans must have been attracted to him too. He's undeniably sexy, if in a sleazy way, with his loose limbed lanky frame, slicked back hair, straw boater and southern style white suits worn with suspenders, like a bizarre cross between a dandy and a rube. If Duryea was merely brutal he wouldn't have been able to get away with manhandling women on film the way he did - he displays a lighthearted, self-mocking quality, especially in his unique drawling, insinuating vocal delivery. Fritz Lang's Scarlet Street was the peak role of Dan Duryea's career, and the closest thing to an out-and-out pimp he ever played. At one point screenwriter Dudley Nichols even gave Duryea a self-referential speech about Hollywood tough guys: "I hear of movie actors getting five, ten thousand a week- and for what? Acting tough. For pushing girls in the face - what do they do I can't do?"

Later in the film, Duryea rears back to slap his girl, Kitty (Joan Bennett), only to pull his punch at the last second, drawling "If I weren't a gentleman...!" The kicker is that he really thinks he is a gentleman - he's completely oblivious to the appalling impression he makes on people. This lack of insight will do much to bring about his downfall.

Scarlet Street is actually a remake of Jean Renoir's 1931 French film La Chienne (The Bitch), adapted from George de la Fouchardiere's novel, the title of which was rendered in English, aptly, as Poor Sap. I recently had the chance to view La Chienne (though unfortunately without English subtitles) and felt that while Renoir's original was very well done, it remained within the bounds of a certain Gallic decorum. Fritz Lang's version was more imaginative, taking the characters and story to wilder extremes. For example, Dan Duryea's counterpart in the French film, Georges Flamant, while even more of a dandy, has little of Duryea's hard edge.

Fritz Lang's films are not often noted for their humor but much of the first two thirds of Scarlet Street is wildly hilarious - a black comedy of errors in which a lethal combination folie a deux/menage a trois proceeds through a series of romantic delusions and absurd venal misperceptions, only to suddenly morph into the bleakest of tragedies, leaving one principal murdered, a second electrocuted for a crime he did not commit, and the third an insane derelict whose very identity has been irretrievably stolen with his own connivance.

The central trio are Dan Duryea's aspiring pimp/con man Johnny Prince, Joan Bennett as Johnny's girl Kitty March aka Lazylegs, who has the instincts of a good whore but is too slothful to actually work at it, and Edward G. Robinson as Christopher Cross, who is both a pathetically naive and repressed trick shackled to a soul destroying shrew of a wife and an extremely talented if untutored and unknown painter. The setting is a dreamlike Greenwich Village, one of the finest studio bound evocations of New York City as strikingly photographed by Milton Krasner.

The chain of mutual manipulation begins where all good film noirs should begin, in the rain in the dark on the streets of the city. Chris Cross, on his way home from a testimonial dinner celebrating his 25 years as a cashier, spots Kitty, irresistibly delectable in her transparent plastic raincoat, being kicked to the rainswept sidewalk by Johnny and bumblingly intervenes with his umbrella to "save" her. Scenting an opportunity, Kitty allows Chris to buy her a drink and is knocked for a loop by his cultured manners and eruditon about art, jumping to the conclusion that he's a wealthy eccentric artist whose paintings sell for up to $50,000. Chris is well aware of her mistaken assumptions about him and leads her on in his passive/aggressive way.

After some unsubtle prodding by Johnny - "Here I am knocking my brains out trying to raise a little capital and this is right in your lap - this bird is goofy about you!" - Kitty decides to do Chris the great "favor" of "letting you help me" by paying the rent, with embezzled cash, on a Village pied-a-terre for her (and Johnny, unknown to him). Chris is to be allowed to paint there on weekends.

Chris's priggish wife Adele, played to the hilt by Rosalind Ivan in a tour de force of anti-sexuality, has demanded that he remove his paintings from their flat, on pain of their destruction. This dialogue between the two is a dead on skewering of the Victorian ideal of marriage:

Adele: If you don't get rid of that trash (his paintings) I swear I'll give it to the junkman! And the things you paint- getting crazier all the time- next thing you'll be painting women without any clothes!

Chris: I've never seen a woman without any clothes.

Adele: I should hope not!

At the time Scarlet Street was made (1945), New York City had supplanted Paris as the world’s center of modern art. Yet in the surprisingly many film noirs that deal with art and its practitioners, modernism is usually treated with sneering condescension and its adherents portrayed as crackpots, or at best, amusing eccentrics (for example, the zany abstractionist played by Elsa Lanchester in The Big Clock). Painters who are portrayed more seriously typically work in “realistic" styles that were already old-fashioned by 1900. Scarlet Street is unique in providing Christopher Cross with paintings that are boldly expressionist as well as believably primitive technically - especially the snake coiled around an El train platform (when Dan Duryea sees it he says of Chris "the poor sap must be a hop-head!") and the piece de resistance - Chris's "self portrait" of Kitty in her baroque black negligee. The paintings were created for the film by John Decker, described by Fritz Lang's biographer Patrick McGilligan as "a rogue who seemed to be everyone (in Hollywood's) friend; his studio was a bohemian hangout for actors and artists."

Dudley Nichol's script also shows an unexpected insight into the business of art. When a big time critic named Janeway and his gallery owner pal take an interest in Chris's unsigned paintings, Johnny Prince has a moment of pure con inspiration - he tells them that Kitty is the artist, much to her dismay:

Kitty: I can't fool that critic.

Johnny: You always wanted to be an actress. Now here's your chance. You've been around the old boy long enough to pick up his lingo. Feed Janeway some of that.

And she does - to such effect that Kitty March is soon the new darling of the N.Y. art world. When Chris finds out, he accepts the situation graciously since he's savvy enough to realize that Kitty's persona is far more exploitable than his own.

But this cozy arrangement goes off the rails when Chris shows up unexpectedly at the apartment and catches Kitty and Johnny in bed together. When Chris tells Kitty he's willing to forgive her, she laughs in his face - the contempt explodes from her uncontrollably like pus from a lanced boil. Chris picks up a handy icepick and plunges it into her cold, cold heart - the only way he's ever going to penetrate her.

When Johnny finds Kitty's body he panics and takes off with her car, money, and jewelry. When the cops pick him up, he regains his aplomb:

Detective: You cleaned her out!

Johnny: Why wouldn't I? She didn't have any more use for them.

This kind of comment doesn't exactly endear him to the authorities, and Johnny is charged with Kitty's murder. When Johnny claims that Chris is the real killer and true creator of the paintings, Chris says that he merely copied Kitty's work. Johnny goes to the chair yelling "Somebody help me!" and Chris, having lost his job, his wife, and his claim to his art, is left to wander the streets of Manhattan, a haunted derelict, engulfed by encroaching shadows.

The scene in Chris's skid row room where, tormented by aural hallucinations of Kitty and Johnny calling one another's names lasciviously, he hangs himself only to be unwillingly rescued by a neighbor, is one of the most powerful and haunting in all film noir. It took tremendous artistry and courage for legendary tough guy Edward G. Robinson to get so deep inside a character who is so humiliated and emasculated, even to the point of wearing a frilly apron when his wife orders him to do the dishes.

Joan Bennett seems to have been quite the femme fatale in life as well as her films. Her husband during the 1940’s and 1950’s was producer Walter Wanger. The couple formed a production company with Fritz Lang which made Scarlet Street as well as two other noirs, The Woman in the Window and Secret Behind the Door. There were many rumors, never quite confirmed, that Joan was having an affair with Lang during the making of these films. But the real payoff came a few years later in 1952, when Walter Wanger shot and wounded Joan Bennett's agent and lover, Jennings Lang (no relation to Fritz) in a Hollywood parking lot. Wanger served a short prison term, and the resulting scandal derailed Joan Bennett's already slipping career. However, the denouement wasn't nearly as bleak as in Scarlet Street - Joan Bennett and Walter Wanger actually stayed together for another thirteen years.

Scarlet Street was banned on its initial release by several local censorship boards, including New York State, Atlanta, & Milwaukee. Fritz Lang and Walter Wanger were forced to organize a press campaign to protest the rulings, and most were ultimately reversed. The objections were not to Dan Duryea’s physical abuse of Joan Bennett, but to various, mostly

trifling, sexual references, such as Duryea insinuatingly asking "Where's the bedroom?" on being shown the Village apartment. Lang actually had to cut that line, as well as reduce the number of times Edward G. Robinson stabs Bennett. As Fritz Lang commented wryly, "Is it immoral to stab a woman seven times but moral to stab her only once?"

#10 The Set Up (1949)

Of the ten films on my list (which are not really in any particular order) The Set Up is the one I have the most pure affection for. The Set Up is generally considered the best of the boxing subgenre of film noir and it's a bit hard to write about it without echoing the work of others. Nicholas Christopher in his evocative book, Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City, summed it up as well as I could: "The world of boxing is truly the noir world in miniature... The most violent, existentially intense, ritualistic and money driven exhibition the city has to offer."

Boxing is the only sport I truly care about. Boxing's inherent drama, raw emotion, and elemental conflict is only equaled by the sheer style, color, and individuality of its practitioners in its classic era, which is roughly equivalent with that of film noir itself. Victory in boxing seems sweeter and defeat can be overwhelmingly crushing - just look at Floyd Patterson who, after losing his heavyweight title to Sonny Liston in 1962, snuck out of an empty Chicago stadium, wearing a phony beard, and fled alone to Madrid, Spain without telling a living soul. Or at the long, slow ride on the night train to terminal city of Sonny Liston after losing his title in turn to Muhammed Ali in 1964. The last stop was his heroin OD in Las Vegas seven years later.

The basic story of The Set Up is classic in its simplicity and bitter irony - the manager of a 20-year veteran journeyman boxer named Stoker Thompson (Robert Ryan) arranges with a mobster named Little Boy (Alan Baxter) that Stoker will take a dive in the third round of his bout with Little Boy's young up-and-coming protege, Tiger Nelson (Hal Fieberling). But the manager Tiny (George Tobias) is so certain Stoker will lose and so unwilling to split the paltry $50 payoff that he refuses to tell Stoker that the fix is in. Of course Stoker has other ideas - beating Tiger Nelson could be his last chance to get back in the big money - or at least enough to open a cigar store or beer joint. After taking an extreme shellacking in perhaps the most bruising movie fight ever (only equaled by the Jake La Motta/Sugar Ray Robinson match in Raging Bull), Stoker summons his last reserve of strength, balls and sheer desperation and knocks out Nelson (going to the brink of collapse himself). Afterward, Stoker receives further punishment from Little Boy and associates for what is, in their eyes, an unpardonable double cross - his hand is smashed with a brick, taking him out of the fight game permanently.

The Set Up is a superb example of the high level of artistry the big studios (in this case, RKO) could achieve within the confines of their soundstages. The entire film takes place in 92 minutes of real time in an area of a few blocks of the seamy, sweltering, nocturnal underbelly of Paradise City, a "tank town" that might be anywhere in the East or Midwest. There's the bleak Hotel Cozy, a diner, a penny arcade, and the Dreamland Ballroom, complete with low rent lotharios prowling outside. But the centerpiece is a decaying ramshackle cavern of an arena, the Paradise City Athletic Club. Tonight there's a card of five boxing matches (although Friday is wrestling night, where "for the first time in Paradise City, they will wrestle in a ring filled with fish!").

This entire microcosm of the noir universe was created on an RKO soundstage and it seems utterly real, down to the last extra in the aimlessly roaming crowds. Another most impressive asset of the major studios was their ability to summon an endless variety of unique character actors and bit players to populate a production. Director Robert Wise and screenwriter Art Cohn (who had a parallel career as a distinguished sportswriter) did extended research at boxing matches at L.A.'s Olympic Auditorium, closely studying the fans for lines and bits of business they could use. Unlike most filmmakers today, these men understood the beauty of ugliness. Each of the fight fans in the film is a distinctive individual with his/her own idiosyncrasies, yet they are united in the way their primitive emotions boil and bubble up from the troubled depths of their stunted souls.

The Mutt and Jeff team of Stoker's manager Tiny (George Tobias) and cornerman Red (Percy Helton) embody the definition of the term "parasite." Tobias usually played cynical-but-likable sidekick types, but here his utter contempt and disregard for Stoker as a human being is all the more appalling for being so offhand. When Red, who lack's Tiny's malice but is too selfish and weak to resist him, keeps suggesting that it might be prudent to enlighten Stoker about the fix, Tiny loses his temper and snaps "How many times do I hafta tell ya? There ain't no sense in smartenin' up a chump!" The lumpish, rat-faced, squeaky voiced Percy Helton has one of the most bizarre personas of any character actor, and excelled at playing sleazes of all varieties. Tiny and Red's loyalty to Stoker amounts to less than zero - when the fix falls apart, they can't even wait for the end of the fight to cut out and are nowhere to be found for the rest of the film.

The atmosphere in the fighters' dressing room, where Stoker and his colleagues await their fate, is a striking contrast to the casual everyday treachery of Tiny and Red, and the unthinking wallowing in primitive emotionalism of the fans. Here Stoker is given a great deal of respect - just surviving twenty years in the fight game with his body and wits still reasonably intact is quite an achievement in itself (even if the fans' attitude is "Where's your wheelchair? He's an old man!"). But beyond that, the fighters' seemingly lighthearted banter actually amounts to a kind of roughhewn philosophical discourse.

For instance, there's the wiry Souza (Phillip Pine), who carries a miniature Bible at all times. When asked why, he replies "I'm a gambling man. I play percentages. There's a price on anything - even heaven. It's a short ender, sure. The odds are a million to one." Mickey, a crass attendant who cheats at solitaire, scoffs "How do ya like dat guy - makin' book on da hereaftah!" and Stoker muses "I don't know - everyone makes book on something." When Souza loses his fight, he's unfazed: "A fight's just a fight. I still got that million to one shot."

Then there's Gus, played by the versatile but always world-weary Wallace Ford, another grizzled seen-it-all veteran who's the head attendant, in charge of preparing the fighters for their bouts. Like Gunboat Johnson, a gnarly little guy who defines the term "broken down." Gunboat is obsessed with the legend of Frankie Manila, who supposedly got beaten 21 times before coming back to become middleweight champ. When Gunboat is carried back to the dressing room after his own inevitable K.O.,the ring doctor, attempting to revive him, asks if he knows his name. Gunboat struggles into brief consciousness and gasps "Frankie Manila!" Gus sums it up in one pithy phrase: "Guess you can only stop so many."

The Set Up must be the only film noir to have a narrative poem (of the same name) as its source material. The poem was written in 1928 by Joseph Moncure Marsh, a young scion of a distinguished American family who also wrote a similar extended poem about silent era Hollywood, The Wild Party, which has been the basis of several film and stage productions. March wrote in a memoir about his life in New York while composing the two poems that he "could usually be found rubbing elbows with prostitutes and gangsters and those wicked people from Show Business, all of whom recognize me as a kindred spirit."

During the 1930's, March left New York for Hollywood, and a checkered career as a screenwriter, writing Hell's Angels for Howard Hughes and once being arrested for stealing a script from Warner Bros' offices during a dispute over plagarization. March's acerbic observations about the screenwriting "racket" are well worth quoting:

Few writers are left alone to write... They are expected to turn something in on paper every few days, and if this does not happen, the producer begins a routine known as "giving the writer the needle."... Harassed in this subtle way, a writer often defeats the producer's purpose by putting down anything he can think of... He writes against time, in desperation, "from hunger" as the saying goes.I haven't had the opportunity to read the poem version of The Set Up, but I did discover that March's main character was a black boxer improbably named Pansy Jones, whose victimization occurs because of his race. March was outraged when the makers of the film changed the character to a white fighter, but by then he was persona non grata at the studios. But a vestige of Pansy Jones remains in the film in the character of the black fighter Luther Hawkins, a very dignified young man who wins the main event, portrayed by the severely underappreciated James Edwards (Joseph Moncure Marsh spent the latter part of his career back in New York, writing and producing industrial films for large corporations, some of which have today acquired a cult following).

I'm not going to go into detail about the deep sensitivity of Robert Ryan's performance, or the masterful realism and sheer sustained violence of the climactic boxing match, since these subjects have been covered at great length elsewhere. But I would like to mention that off-screen, both Ryan and Hal Fieberling, who played Tiger Nelson, were boxers of long experience, Fieberling being a pro fighter trying his hand at acting and Ryan having been a four time college champ at Dartmouth. The fight was choreographed by another pro boxer, John Indrisano.

Audrey Totter's role as Stoker's wife Julie was an unusual one for her, both because it was a sympathetic one as opposed to her usual femme fatale, but also because she only has one substantial speech in the whole film, in their room at the Hotel Cozy where she tries to convince Stoker that he's reached the point of diminishing returns:

Stoker: A top spot... and I'm just one punch away.

Julie: Don't you see? You'll always be one punch away. How many beatings do you have to take? Maybe you can go on taking the beatings... I can't.

Stoker: Well, that's the way it is. When you're a fighter, you have to fight.

But Totter's really extraordinary scene is almost entirely without dialogue. She leaves the hotel and crosses the street to the arena but can't bring herself to go in, then wanders around the shabby streets. Her only line comes when she's accosted outside the Dreamland Ballroom by a hick roue: "Bet ya do a mean rhumba?" She shuts him down with a definitive "Beat it!," then walks out onto a viaduct above the railroad tracks where she stops, tears up her complimentary fight ticket and watches the pieces flutter onto the passing trains below. In this one sequence, with virtually no lines, Audrey Totter communicates more emotion than many of today's actors do in their entire careers - immeasurably aided by Milton Krasner's photography. The noir filmmakers knew how to make all the elements of a film work together to heighten emotion, not flatten it as is so often the case today.

This hypnotic brand of amplified, stylized reality is even more evident in the final scene of Stoker's beating at the hands of Little Boy and his minions. Alan Baxter as the implacable Little Boy in his immaculate white suit is very effective here. After all, Little Boy is enforcing a code of conduct he believes in: "I paid for something tonight and I didn't get it. I don't like anyone to welsh."

I took the following notes while watching the final moments of The Set Up; they perhaps convey the feel of it better than more polished prose:

Stoker tries to find a way out of the deserted, filthy arena - runs down rows of empty seats to the ring - tries endless locked doors - finally one opens - he steps out into the alley. The street seems empty - boppish music from dance hall - they see him, Little Boy, Nelson, Danny & one more - Stoker backs down the alley to a dead end, desperately tries to pull up accordion door: "All right Stoker, we'll talk now!" They're on him - "That's it- hold him."

Bluesy driving riffs in background - Stoker rears up and gives Little Boy a shot in the jaw - "I said hold him!" - "You'll never hit anybody with that hand again" - we see shadow of trumpet and drums on alley wall as arms crash down on Stoker - drums pound.

Music shifts to sweet melody in waltz time on clarinet and trumpet - teenagers come out on to fire escape above - Stoker painfully struggles to his feet - "boy does he have a snootful."

Garbage cans crash - teenage girl twitters - Stoker excruciatingly inches toward street leaning on wall- "Julie! Julie!"- Julie sees him from window and rushes downstairs - "I'm here Bill. What did they do to you?" "They busted it for good. With a brick. Wouldn't do it. They wanted me to lay down. I was takin' that kid... Julie... I can't fight no more... I won tonight."

"Yes, you won- we both won tonight"- wail of ambulance.

THE END