Working the Line, Working the Crowd

Period singles, courtesy of The Indiana 45s website

Indianapolis Politics, Labor, and the Economy Soul

by Jeff Kollath

(October 2012)

"I was at work at Ford Motor Company at the time. I was a production checker, so I could always get away and take a break, and then catch up. So I went into a bathroom, blocked the door, got some cardboard and sat on the toilet. I wrote the "Funky 16 Corners" in like 10 minutes. I write on ideas - if something comes to my head, I write about it. I'd completed the song while I was on the line, singing parts.

For nearly a century, the west side of Indianapolis had been home to the majority of the city's black community. The area was a commercial and cultural center, where African Americans went to purchase goods and services from black-owned businesses, meet their friends and neighbors, dine out, and hear live music. As the Indiana University and the interstate highway infringed on the neighborhood, thousands of African Americans moved out, or were forced out of the area. By the mid seventies, all that was left of the Indiana Avenue neighborhood were abandoned buildings, dilapidated homes, and a shattered legacy of what used to be. At the same time, the formation of Unigov, the linked city-county government, sapped African Americans of the political power that they had worked for so long to obtain. Unigov added nearly 250,000 new white voters, which grossly outnumbered the number of new black voters that came into the community. Blacks felt misrepresented and uncared for as the white-run city government focused on issues that did not address the immediate concerns of the black community.

After dealing with de facto segregation for nearly one hundred years, African Americans finally had obtained the freedom to live anywhere within the city of Indianapolis. Compared cities of similar size, Indianapolis had the highest percentage of black home ownership, a key statistic but it does not take into account the quality of said domiciles. Industries, especially the GM and Ford auto plants, RCA, and meat packers, regularly hired African Americans, yet many of them were unskilled positions or in the service industry. Unemployment for the entire city hovered near 3%, but for black residents it remained around 9%. While lower than other Northern industrial cities like Detroit, Chicago, and Cincinnati, high paying, high status, and skilled positions continued to elude many of Indianapolis' black residents. Educational opportunities remained uneven as well.

A constant in the black community during this era of tension and change was the many local soul and funk bands that played live in nightclubs throughout the city and released dozens of records. They reflected and supported the community's moderate political stance. The music uplifted listeners, made them dance, and helped them forget about their problems if only for a brief moment. Songs also contained positive messages that sought to improve the well being of the community and improve community pride and unity. Songs such as "Soul City," "Tightening Your Popcorn" and "Funky 16 Corners," all made listeners feel proud of being from "Naptown U.S.A.," a place where there is good music, good dancing, and most importantly, great people. There were no songs released by Indianapolis musicians that threatened or alienated any section of the black population. Musicians sought "to do better by people," and wanted to improve life in Indianapolis rather than foment violence or anything that could damage the well being of the black community.

In a variety of ways, locally produced soul and funk music served as the "cultural glue" that held much of Indianapolis' black community together during the late sixties and early seventies. Records produced in Indianapolis were recorded by Indianapolis bands and released on Indianapolis record labels. Because the musicians, the producers, and the record company executives were from the local black community they understood the desires of the listeners. They knew what issues were important to the community and what types of songs were popular, and they geared their releases to cater to local record buyers. Local musicians were just "everyday people making records" and the messages in their songs resonated with an audience made up of family, friends, and neighbors.1

As the hosts of live performances by local soul and funk bands, Indianapolis nightclubs achieved great importance during the late '60's and early '70's. Although the local nightclub scene had prospered during the '30's and '40's when Indianapolis was nationally known for its jazz clubs and artists, by the mid-sixties, the scene began to dwindle as club goers became disinterested in local music. Beginning in 1967-68, as more talented bands took to the stage and local companies began to release records, interest in the local soul and funk scene increased dramatically. Local nightclubs resumed their role as cultural meeting places, where friends and neighbors met for live music and dancing. Nightclub programming, from live soul and funk music to exotic dancers, reflected and supported the entertainment desires of the local black community. Social clubs resumed booking meetings, dances, fundraisers, and matinees at nightclubs, most of which featured live music from a local soul outfit. Many social clubs held charitable events at nightclubs that brought the local community together to help their own and generally improve life for all African Americans in the city.

The topic of how Indianapolis' black community and soul music coexisted is significant for several reasons. Using soul music to examine the political and cultural views of Indianapolis is important because it emphasizes how Circle City musicians recorded music specifically for the local black community. Indianapolis musicians wrote songs based on their knowledge of the local black community, their political and cultural values, and their desires and tastes. Songs like "Soul City" and "Tightening Your Popcorn," which explicitly champion Indianapolis residents' prowess as partiers and dancers, gave the music a regional flair, and when combined with the notion that the musicians were an important part of the community, made Indianapolis soul and funk scene so important to the black community. It spoke directly to and for them, and thus, created an economy of soul. This included a rise in nightclub attendance, the creation of black owned record labels that highlighted local artists, and greater opportunity for local musicians to earn a living, all of which occurred at a time when threats to Indianapolis' black community were at an all time high.

The focus of this essay will be the interrelationship between labor and music within Indianapolis' African-American community during the Civil Rights Era. Despite the myriad changes that affected Indy's black community from 1966 to 1974, from the formation of UNIGOV, a unified city-county government, and the development of a downtown Indiana University campus to discrepancies in housing and hiring practices and the degradation of the historically black Indiana Avenue neighborhood, the music and nightclub scene expanded in numbers of clubs and performers, and footprint throughout the city. While the glory days of the Indiana Avenue jazz scene some twenty and thirty years earlier could never be relived, this new nightclub scene reflected the politics and culture of the era, and provided Indy's black community a chance to unwind after a long and arduous work week.

BLACK INDIANAPOLIS, 1968-74

Throughout the twentieth century, Indianapolis' African-American community worked diligently for respect, equal rights, and an opportunity to be successful in a city where it had long been neglected and repressed. When African Americans first came to Indianapolis in the mid-nineteenth century, they were relegated to the swamps in the western part of the city, which is where the Indiana Avenue neighborhood eventually came to be. Prejudice was a dominant factor in the lives of many African Americans; blacks were discriminated against in nearly every facet of life, from renting and purchasing real estate to finding jobs.

By 1968, African Americans in Marion County were becoming the base of the city's Democratic majority. Neighborhoods heavily populated by African Americans were known to swing entire elections towards the Democratic side. The population of African Americans in Indianapolis was ever-growing as well, as blacks made up 27 percent of the voter base, up from 21 percent in 1960 and 15 percent in 1950. The improving political influence of Indianapolis' African-American community took a tremendous blow in 1969, however, with the formation of the unified city-county government, or Unigov. 2

After the 1968 elections, Republicans led by recently elected Mayor Richard Lugar controlled most of the political entities in Marion County and Indiana, including the Governor's Mansion, the Indianapolis City Council, the Marion County Council and both houses of General Assembly. In fact, Lugar was only the third Republican mayor in Indianapolis since 1925. With this stronghold in place, Mayor Lugar set about his plan to consolidate the legislative and executive bodies of the city of Indianapolis and Marion County, creating a single strong council and single county-wide executive.3

Despite promises of equity and fairness, Unigov was met with staunch resistance from both Marion County Democrats and Indianapolis' black population. Democrats called the proposal "Unigrab" based on the substantial advantage gained by Republicans in shifting power to the substantially white outlying areas of Marion County. The addition of 250,000 additional white constituents to the Indianapolis voting registers was of great concern to the African-American community. Although Lugar still contends today that diluting minority voter strength was not a goal of Unigov, prominent black citizens and activists such as Willard Ransom, Sr. disagree. Ransom, head of the local NAACP in the 1960's, felt Unigov was the death knell for Indiana Avenue and markedly changed Indianapolis' black community. In an interview, he recalled that "Lugar brought the worst curse on all of us - Unigov. We fought him on that but he got it through. That brought the outlying areas of the city to vote. [Unigov] was the big thing that Lugar did that was bad for blacks."4 Black political clout and blacks' growing majority within the Democratic party, which until Lugar's election controlled the city of Indianapolis, was gone by 1970.

Not only did African Americans see the lessening of their political power during the late 1960's, but they also witnessed the deterioration of their historic Indiana Avenue community. One reason for the great change in the Indiana Avenue neighborhood was the desegregation of Indianapolis neighborhoods. When Indianapolis was settled in the nineteenth century, the Indiana Avenue area was a mosquito-infested swamp deemed unsuitable for mass settlement. However, with restrictive housing covenants and overt racism keeping blacks from inhabiting white neighborhoods, blacks were left with few options and eventually took up residence in the Indiana Avenue area. The blacks who did live outside the area commonly paid up to 21 percent more than white residents for a comparable property.5 Until the early 1960's, de facto segregation was prevalent throughout the city. This concentrated black residences and businesses in one area, making Indiana Avenue the economic, social and cultural focus of the black community. Black-owned grocery stores, drug stores, clothing stores, and of course nightclubs, ran the entire length of Indiana Avenue. Crispus Attucks High School graduate and NBA legend Oscar Robertson believes that the Avenue was created by the white community in order to contain local blacks. He said, "Indiana Avenue was the center of everything for black people. It seems that the white power structure said, 'OK, if you're going to do it, do it right here so we can watch you.'"6

Although the segregation present in Indianapolis during the 1950's and '60's was never an official policy, it was omnipresent in the lives of most African-Americans. The majority of African-American citizens lived either in the Indiana Avenue area or near Martindale Avenue on the east side of Indianapolis. Several restaurants, including the Evans Restaurant on College Avenue, refused to serve blacks as late as the 1950's, while the Riverside Amusement Park allowed black customers only one day a year.7 The restrictive housing covenants that kept blacks out of most neighborhoods began to collapse, however, in the 1950's. Many African Americans left the Indiana Avenue neighborhood for greener pastures, specifically an area between 30th and 38th Streets, from Meridian Street on the east to Northwestern Avenue, which became the new area for black houses, small businesses, and nightclubs.

LABOR

While located firmly in the heart of the Midwest, Indianapolis is very much a Northern city with a Southern mentality. It is an industrialized city with numerous manual labor jobs, union shops, but it has been incredibly racially charged since the days of D.C. Stephenson and the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920. De facto, or outright segregation, was the rule, making it difficult for black laborers to get ahead and into jobs at the "good" companies like Allison Transmission or RCA. Hiring of black workers increased greatly in the mid-1960's as total unemployment hovered around 3%. Workers, regardless of color, were needed to keep industry moving forward, and the city saw a great deal of corporate expansion during this era.

Further, numerous small, black-owned businesses dotted the city, especially in the Indiana Avenue neighborhood, but those businesses were subject to "regionality," supported and successful when the population was there, but when it leaves, so does the business. When the black population began to leave the Indiana Avenue neighborhood, the shops, auto mechanics, taverns and more eventually closed. Skilled craftsmen, like plumbers, bricklayers, and carpenters, constantly dealt with limitations, being held out of apprenticeships (unless they had family connections) and restricted from union activity. Advanced education did not help much either, as numerous black college graduates could only find work on the loading dock instead of in the office. Critical, though, to realize that despite the issues black workers faced, there were jobs, and in turn, there was home ownership, automobile ownership, community investment, and most importantly for local musicians, disposable income to go to clubs & buy records.

STRESSES ON THE BLACK COMMUNITY

During the mid-1960's, there was more interstate construction in Marion County than any other county in the United States.8 This construction greatly altered the racial geography of Indianapolis. Despite community efforts and the involvement of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) on behalf of the local Homes Before Highway Commission, the highway split the Westside black community in two. Indiana State Representative William Crawford, a former resident of Lockefield Gardens, believed this was the biggest generator of change within the black community. In a 1994 interview, Crawford said, "The strain occurred when they ran the inner-loop of I-65 right through the heart of the African-American community and that disrupted and displaced a lot of people. That was the catalyst of the deterioration process."9 Not only were people displaced, but also the city of Indianapolis offered them little help. Despite an influx of federal money, and the construction of new housing, it remains unclear whether or not the city used any money to house those repositioned from the Indiana Avenue neighborhood.10

The construction of the Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis campus also caused great consternation along Indiana Avenue. Beginning in 1962, the university gradually began acquiring property in the area, and although no one was forced out, the residential community began to erode. By 1971, IUPUI had purchased 751 parcels of land, mainly single-family houses, but also taverns, liquor stores and several churches.11 Those in the black community appeared bitter about the land takeover, accusing the city of allowing IUPUI to expand and modernize while doing nothing to improve life for the residents of the area.12 Many feared that some of their local landmarks, namely Lockefield Gardens and the 11th Street YMCA, faced elimination, while others came to the realization that they would have to leave their homes. "They [were] not going to put 30 to 40 thousand people in the Indiana Purdue and hospital complex and leave [that] many Negroes in the vicinity," one resident concluded.13 By 1970, 75 percent of Indiana Avenue inhabitants were tenants, many times transients with little interest in community preservation. Owners of these houses rarely lived on the Avenue anymore, so when word got around that IUPUI was starting to purchase homes along the Avenue, landlords flocked to the IUPUI Real Estate Office looking for the best deal. High renter turnover, low rate of return on rent, and lack of social supports prompted landlords to sell out. IUPUI then took over the properties, essentially becoming the landlord for thousands of people. Although IUPUI claimed their relocation was done in a humane way, the school was placed in an "exposed position" to take the blame for the problems caused by the displacement. According to former university administrator Charles Hardy, IUPUI forced no one from their residence until they found alternative housing, oftentimes with help from the university.14

From 1960 to 1970, each Indiana Avenue census tract lost over 2,000 residents, although the percentage of black residents in the area remained consistent since whites also left. A lack of quality housing was also an issue, as properties around the Indiana Avenue neighborhood became decrepit and many were condemned, vacated, and eventually destroyed. Although IUPUI helped many families relocate, there were others who could not afford to do so. Aside from Lockefield Gardens, there was little or no public housing, and nearly one-third of families were living in poverty.15

A close examination of U.S. census data reveals the migration of black population away from Indiana Avenue and towards 30th Street. Although this neighborhood never reached the pinnacle of community pride that Indiana Avenue had in the 1930's, it became another large black settlement in Indianapolis, and one with its own distinct nightlife and cultural scene that briefly prospered from 1968 to the early-mid '70's.

THE INDIANA AVENUE MUSIC SCENE

During Indiana Avenue's heyday in the thirties and forties, nationally renowned acts like Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, and Fletcher Henderson frequently stopped in the Circle City for a gig at a club or the Walker Theatre. Indianapolis was once a hub for national artists, and was once dubbed the "Jazz Capitol of the Midwest."16 However, by 1968, Indianapolis became just another tour stop for some artists, while others did not bother passing through. Vibist Billy Wooten remarked, "I'd heard all these wonderful stories about this town called Indianapolis. I was always begging my agent, 'Send us through Indianapolis!' I figured I'd do some research, meet some of the old [jazz] guys. As young guys growing up, we'd hear about these fantastic musicians and all these places to play in Indy. [But] my agent said, 'You don't want to go there, there's nothing there anymore!'"17 What Wooten's agent referred to was the apparent lack of exciting music happening in Indianapolis during the late 1960's and early 1970's. The legacy of the Avenue was still ingrained in the minds of agents, musicians and club-goers, and anything less was deemed unsatisfactory. Since the Avenue was dying, it was assumed by most that Indianapolis' music scene was dying along with it, and the moniker "Naptown" seemed quite appropriate in describing nightlife in the Circle City.

Despite the strong cultural legacy of the Indiana Avenue entertainment district, it was not exempt from the many tensions that tore at the seams of the black community during the late sixties and early seventies. The construction of I-65 and IUPUI had pushed a large portion of the neighborhood's black population to areas north of 30th Street. As a result, black-owned businesses either left the area or closed up and there was little or no new money coming in. By the early seventies, the neighborhood had become one of the worst slums in town. Drug use and violence also changed the face of the Avenue, driving people away from local businesses and keeping patrons out of the nightclubs. White residents regularly patronized Avenue jazz clubs, but as violence and anti-white sentiments grew, their presence greatly decreased.18 Black residents who had historically visited Sunset Terrace, the Blue Eagle, the Place to Play, and the Flame now patronized the 20 Grand, the Demonstrators Club, the Hub-Bub and other near North side clubs. For the most part, club goers had regional tastes, preferring not to travel across town on a Friday or Saturday night and choosing instead to stay close to home. The growing popularity of nightclubs north of 30th Street along with the many tensions that affected the Indiana Avenue community further deteriorated the nightclub scene along the Avenue and led to the closing of many nightclubs that once prospered.

When the neighborhoods north of 30th Street opened up to the black population in the mid-sixties, businesses that catered to the black community soon followed. Grocery stores, restaurants, and laundromats opened up to serve this new population, as did several nightclubs. The newer nightclubs that sprouted up north of 30th Street reflected and supported the growing black community taking shape there and were slightly different than their counterparts located on Indiana Avenue. The owners of the Demonstrators Club, the 20 Grand Ballroom, and the 19th Hole put a lot of money into building new structures or refurbishing existing buildings and helped create a new and exciting setting for live music and dancing. While Indiana Avenue clubs were not able to attract big name national artists, these new clubs had the facilities and money to do just that. These clubs also became the popular spots for many local bands, many of whom never returned to the Avenue once they got a steady job at a place like the 20 Grand or the Hub-Bub. Entrenched in the community, these new clubs organized fundraisers for worthy causes and played an instrumental role in bringing the black community together.

Local bands were the main form of entertainment at Indianapolis nightclubs, but nationally known soul and funk artists passed through Indianapolis as well. During the thirties and forties, nearly every major jazz artist passed through Indianapolis, and during the late sixties and early seventies, most major soul and funk artists played local nightclubs, the Convention Center, the State Fair Coliseum, and Bush Stadium. Prominent national acts like Booker T. and the MGs, Solomon Burke, and Al Green graced the stages at the 20 Grand and Demonstrators clubs, while James Brown and Aretha Franklin played to thousands of people in larger venues.19 Prior to 1968, many national artists avoided Indianapolis because there were few adequate venues that could house their performances. However, with the opening of several large clubs, national artists began to return and so did the crowds.

One of the many differences between Indiana Avenue clubs and those elsewhere was the number of prominent national artists who frequented these large new nightclubs. At the forefront of these establishments was the 20 Grand Show Lounge on West 34th Street. A former bowling alley, the 20 Grand, which could hold nearly 2,000 patrons, was one of the largest nightclubs in town and featured popular national acts such as Funkadelic, King Floyd, Maceo Parker and Rufus Thomas.20 The 20 Grand also featured special attractions nearly every night of the week, such as ladies night and amateur talent shows. Admission prices were high, ranging anywhere from three to six dollars depending on the act. To assuage the burden of this high cover charge, the club oftentimes held dance contests that paid as much as $100 to the winner.

Despite the many concerts put on by nationally known artists, the Demonstrators Club on Central Avenue hosted Solomon Burke, Eddie Harris, and Al Green but was best known as host to the many gatherings for Indianapolis' African-American social clubs. In fact, the Demonstrators Club was a social club unto itself, holding meetings at the club while also featuring live music, an open bar and the "Miss Demonstrators" beauty pageant. Although social clubs were a longstanding tradition in the city, they were traditionally for older couples or young debutantes. Clubs such as the Penguins, the Soul Survivors and social sororities frequently posted meeting reviews and photos on the society page of the Recorder. Other clubs such as the Soul Babes Social and Charity Club and the Blackinizers were heavily involved in charitable activities, putting on matinees during the holiday season to raise money or presenting Santa Claus at a neighborhood community center.21

The matinee was a highly popular enterprise in Indianapolis, and the city was eventually deemed a "matinee, club-type city," a far cry from the late night, all night, club going atmosphere of glory days of Indiana Avenue. Yet, it was these many options - multiple clubs to play at, shows more than just on the weekends, and two matinees per weekend - that provided another avenue for supplementary income and employment for Indianapolis many black musicians. Again, while black unemployment remained higher than it did for white residents of Indianapolis, and advancement or skilled labor opportunities were limited, the overwhelming success of the nightclub scene, the numerous record companies that sprouted during, and the support these endeavors by the local community reinforce higher levels of disposable income and the importance of the 'soul economy.'

Like the great jazz and chitlin circuit scene along Denver and Sea Ferguson's Indiana Avenue of the 1930's and '40's died out, so too did the night club revival of the late '60's and early '70's. Bands that never needed to leave Indianapolis to play and make a living now left to tour the continent, while others, such as the Rhythm Machine, sought out a new home base, eventually landing in Des Moines, Iowa. A change in interest from live music to other forms of entertainment coincided with rising unemployment and few opportunities for African Americans in Indianapolis - the malaise and downturn of the 1970's hit Indianapolis hard, and the 'Naptown' name became not a sign of pride, but of a sleepy city clinging to its former glory.

Jimmy Guilford, photo from Cool City Swing Band

FOOTNOTES:

1. Interview, author with James Bell, musician, December 9, 2002.

2. William A. Blomquist, "Unigov and Political Participation" in David Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, editors, Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994), 1356. By the late sixties, African-Americans made up 57 percent of Marion County's Democratic voters.

3. William A. Blomquist, "Creation of Unigov (1967-1971)" in Bodenhamer and Barrows, Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 1351. Fire and police departments and local school districts were not consolidated. Also, the towns of Beech Grove, Southport, Speedway and Lawrence were not absorbed by Unigov.

4. As quoted in Fred Ramos and Steve Hammer, "The Death of a Black Neighborhood: It's A Lot Different Now Along Indiana Avenue," NUVO Newsweekly, July 20-27, 1994.

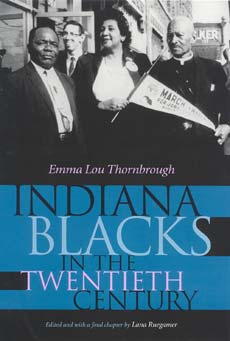

5. Emma Lou Thornbrough, Since Emancipation: A Short History of Indiana Negroes, 1861-1963 (Indianapolis: Indiana Division, American Negro Emancipation Centennial Authority, 1963), 28.

6. As quoted in Ramos and Hammer, "The Death of a Black Neighborhood: It's A Lot Different Now Along Indiana Avenue," NUVO Newsweekly, July 20-27, 1994.

7. Interview, author with Representative William Crawford, December 20, 2002.

8. Interview, Philip V. Scarpino and Sheila Goodenough with Charles Hardy, Head of the Real Estate Office of Indiana University at Indianapolis from 1962 to 1971, October 27, 1989, bound transcription, Ruth Lilly Special Collections and Archives, IUPUI.

9. As quoted in Ramos and Hammer, "The Death of a Black Neighborhood," NUVO Newsweekly, July 20-27, 1994.

10. Kenneth L. Kusmer, "The Black Urban Experience in America," in Darlene Clark Hine, ed., State of Afro-American History: Past, Present, and Future (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986), 91-122.

11. Interview, Philip V. Scarpino and Sheila Goodenough with Charles Hardy, Head of the Real Estate Office of Indiana University at Indianapolis from 1962 to 1971, January 3, 1990, bound transcription, Ruth Lilly Special Collections and Archives, IUPUI.

12. As quoted by John I. Lands, executive director of the Fall Creek YMCA and founder of Our Market, in the Indianapolis Star, December 2, 1979.

13. Recorder, "The Avenoo" column by The Saint, June 27, 1970.

14. Interview, Scarpino and Goodenough with Charles Hardy, 1990.

15. The mean incomes for the 1970 census tracts adjacent to Indiana Avenue were as follows: Tract 3534 - $2,152, Tract 3535 - $1,658, Tract 3540 - $1,857. "Income Characteristics of the General Population," Census Tracts: Indianapolis, Indiana Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, April 1972).

16. Indianapolis Recorder, advertisement for Donald Byrd and the Blackbyrds at the Indiana Convention Center, August 31, 1974.

17. Interview, Eothen Alapatt with Billy Wooten, vibist and Indianapolis musician, Summer, 2001, online transcription, Stones Throw Records. Accessed March 11, 2002.

18. Interview, author with Jimmy Guilford, musician and club owner, March 22, 2002.

19. Indianapolis Recorder, advertisement for Solomon Burke at the Demonstrators Club, October 9, 1971; Recorder, advertisement for Al Green at the Demonstrators Club, November 13, 1971; Recorder, advertisement for Booker T. and the MGs at the Riverside Ballroom, October 7, 1967.

20. Recorder, advertisement for Rufus Thomas at the 20 Grand Ballroom, February 7, 1970; Recorder, advertisement for Maceo Parker and all the King's Men, April 10, 1971.

21. Recorder, photo caption of the Blackinizer's Christmas program at the Haughville Community Center, December 15, 1973.