Approaches to Improvisation

Marilyn Crispell

by Markos Zografos

(February 2007)

Brisbane Convention Centre, Australia, 17 October, 2004

1. Introduction

I'm going to be discussing improvisation and the various ways it can be approached. Some improvisational techniques will be briefly explored from the point of ideas and thoughts about how we can organise music.

This breakdown of a current understanding of improvisation will either be very obvious to someone sitting in a seat here, or it may be something completely foreign to someone accustomed to systematised ways of learning music. Essentially, we're talking about creating music within the limits of sound rather than limits of different ways we write down and understand musical structures and systems of thought in playing someone else's composition.

Though an overview of improvisational techniques, it will be no different to an overview of compositional techniques, as at the level of ideas, improvisation and composition are the same thing. The best definition that I've so far heard of improvisation is that it is "spontaneous composition."

So there's the difference between the two--improvisation is a spontaneous act, composition is a planned act. There is intermingling and all sorts of degrees between them, but we'll be talking about approaching this spontaneity, and different ways we may prepare for such a thing. It is thus similar to written composition; the difference being where the writing composer prepares a work by planning it, the improviser doesn't plan, but can prepare for the spontaneous act through various methods that I'll be discussing.

I am going to refer to the article "Elements of Improvisation" written by pianist Marilyn Crispell as a springboard to commentate upon, as she has given a concise and direct overview of the span of compositional techniques. For those of you that don't know, Marilyn Crispell is an active pianist working in America who combines improvisation with written composition and performs solo, and in various ensembles.

After going through these elements, I'll move onto a discussion about the "spontaneous" part of the improvising act, talking about some ideas on energy flow, timing, and degrees of control--issues to do with the moment of acting out an improvisation.

So it's a very simple topic. It falls into two parts: The first part will deal with materials, matter--the preparatory side of improvisation where you build up your base of musical "availabilities," your attributes; and in the second part we will get into some aspects of movement and energy--the action side of improvising, where you put your material into real-time flow.

So even though this is a talk about improvisation, here we do not make any separation between performance, composition, and improvisation. We just use the word "improvisation" to discuss these three as a single practical phenomenon

2. Elements of Improvisation

I'll now refer to Marilyn Crispell's article "Elements of Improvisation" (which can be found in the John Zorn edited book Arcana) because:

- it outlines the variety of ways a musical composition can be constructed and developed,

- and it does not refer to any specific kind of musical language, but it details what forms the base of anything that we can call "music."

The techniques outlined should be fundamental to any composer's understanding of musical workability, and I'd like to think that everybody who calls themselves "a musician" holds this basic understanding of how music can be constructed.

(I have added numeric points to statements in this article for points of reference to this discussion.)

Elements of composition:A very simple yet broad statement, and one that stands as a foundation of all music and musical styles. Ask yourself:1. The use of rhythmic, melodic and harmonic elements and motives (two or more elements joined together to form a logical whole) in the development of an improvisation/composition

(Improvisation as spontaneous composition)

Adding together motives (as moveable ‘blocks', or permutations) to form compositions

"What level of interest do I have in rhythm?"From these questions, there will arise in you a general partitioning of interest between the three elements. You can say: "from analysing my musical interests I have found that I seem to have more of an interest in rhythm than melody or harmony"...

"What level of interest do I have in melody?"

"What level of interest do I have in harmony?""What piece/s of music (it could be either a single work or an entire style)

adhere to this interest in rhythm?... in melody?

... in harmony?"

and you go on...The most important thing in this self-inquiry is to try to be as honest as possible. This is somewhat achieved by tracing your own personal experience to these elements; and this doesn't at all refer to only looking at technical musical issues. For example, "I like the sound of this percussion instrument because it reminds me of when it used to storm on the roof where I lived on Barry Street," etc."Why do I have more of an interest in rhythm than melody or harmony?"

...and you can come up with all sorts of answers.

So you list those things that form your personal interest...it may look something like this:

| Rhythm | Melody | Harmony |

| high energy, intensity, non-tempo, broken/irregular rhythm but with continuous drive not discontinuous gestures, Cecil Taylor, Stockhausen, car accelerating/decelerating, bouncing ball, electronic artists with irregular rhythms yet sense of tempo (autechre, merzbow), verbal/spoken rhythm (Spanish, Japanese), rap, Rite of Spring movts. 2 through 6, Messiaen "Par Lui tout..."... | romantic song-like (Chopin, Scriabin), for fantasy-like feel usually like minor key orientation with chromatic movements & serial/clusteral harmonies, counterpoint, sequences, invention-like & fake fugues, 2-3-4 parts, funny/playful, (Makigami Koichi, Ruins, Sun Ra, Rodion Schedrin, Ornette Coleman), birdsong, that song on the radio the other night... | clusteral morphings (Scelsi, Xenakis orchestral works), piano serial music (Donald Martino piano sonata, Boulez and Barraqué piano sonatas), for sparsity & gestural power, almost romantic use of octaves with 9th and 2nd extensions (Ustvolskaya), always serialising/equalising materials, piano as 88-note sound continuum—textural approach to harmony mixed with traditional approach where it feels right... |

This forms your "disposal" of personal attributes that you have the ability to use, your uniqueness. I say "disposal" because, for the sake of originality, it is an aim to have no clearly defined piece of information in your memory storage to reference. That is, if you are aiming toward your own style you do not want to simply riff out other people's styles. If you are not seeking originality then this is not so important. So at your disposal is your "junk heap" of musical information; a mud of experiences and imagination-entwined fodder.

Your disposal is something that will always reference your musical personality, so being as honestly aware of it as possible allows you to delve into certain areas more than others, to practice elements and build up this uniqueness however you desire.

This means, for example, that you don't necessarily have to only do physical practice at the instrument; it could be an analysis, for example, of the ways in which "Johnson" uses rhythm and adds together motives in his Symphony number whatever; or it could be just listening to the general feel of a few pieces in a row then trying to keep that same wavelength going—(this is an exercise which can be worked on by following a four-bar phrase in a given style by four of your own bars continuing it...demonstration on the piano)—either on your instrument or in your head; it could be imagining other instruments or people playing them (demonstration of Petar Gocic's saxophone playing)... all kinds of things.

The most important thing is to experiment. Try a lot of different approaches always with the focus of what you want to achieve out of it. For example, a short snappy rhythmic piece; a piece which expresses the mood of a particular scene in a film—after all, this is how my grandmother and others improvised in theaters in the days of silent movies: galloping rhythms when the hero rode to the heroines rescue, dreamy music as they kissed, wild as a fight was going on, etc. These are all good exercises-- they can be just fifteen seconds each.

This is the only way to keep in line with your potential, otherwise you stroll behind it. Improvisation has a very close link with experimentation and the expansion of musical vocabulary purely for the fact that its momentary exposition allows an opening for all sorts of unexpected avenues. So the more you experiment, the more pathways open up for you that you would never have expected otherwise.

2. Beginning with an interval (the most primal musical relationship), rhythmic figure, harmonic block (a ‘block' of harmony in and of itself, not necessarily related to traditional harmonic function within the major/minor tonality system—harmony used for purity of sound (i), or any combination of these, and transposing them (ii), adding imitative/continuous elements, or contrasting elements.

(i) relating to "harmonic block (a ‘block' of harmony in and of itself, not necessarily related to traditional harmonic function within the major/minor tonality system--harmony used for purity of sound)."What Crispell is talking about here is a vision of harmony, not from traditional systems that we may all be used to, that differentiate consonance and dissonance, but harmony from a point of view aiming to perceive continuity in sound, rather than the expected musical outcome.

So what is harmony? Harmony is things put together that work, operating cooperatively, in balance. Notions such as consonance and dissonance are relative and non-existent outside systems that make claim to them, that is, subject to the one's perception. Harmony is achieved at the level of a sound-based musical approach by operating upon a common level of energy fluctuation--nothing else is needed. I will discuss this in a bit more detail later on.

(ii) relating to "any combination of these, and transposing them, adding imitative/continuous elements, or contrasting elements."This comment begins to delve into what will be your second material disposal: the "how do I combine what is in my first disposal to form a developed structure?" disposal.

Once again, the question "what do I like?" arises:

"I like the way Stravinsky's Rite of Spring has a driving rhythmic intensity and how it builds up to these big climaxes. I also like the way I feel this kind of intensity in a lot of pop music--metal, hip hop, electronic stuff--but I prefer the way Stravinsky is able to fuse these elements this way rather than sticking to a repetitive motivic structure that the pop musics follow. I prefer the developmental method, continuous change rather than abrupt/contrasting change, so I am going to see how I can mix the kinds of rhythms I like with this kind of development"

...and from this decision come the experiments...study a score you like, listen to separate elements analytically, aural analysis, always listening to take what you learn into the practical context. Try out different methods... Do they work? Don't they? Why does it/doesn't it work?

"Eh, it sounds too much like I'm just trying to sound like Stravinsky..."

So once it's worked over to a point where you feel you want to move on, forget about it and move onto something else. The process here is that you research musical availabilities and test the results in a practical fashion, like a musical scientist. The more this process happens in the more varieties of ways, and depending upon the level of your self-critical awareness, the more you build up your musical uniqueness.

So to cap what we have so far: We have two disposals to work with and build upon--the first dealing with concrete musical elements, the second dealing with how to combine these elements.

Relating the methods of combination to a melodic context Crispell continues with:

Beginning with a melodic line and varying it in any possible manner (transposition, retrograde, inversion, etc.); melodic lines made by clusters (iii); the importance of the shape of a line; modulation from one motif to another: can be abrupt/contrasting or continuous/evolving (iv).Here, Crispell describes a scale as simply a chosen selection of notes. You can create another disposal (version of a scale) here if you'd like to have a preparation of different scales. Styles that we're used to listening to, Western styles, Eastern styles, have prepared disposals here that you can use, you know, like a C-major scale or a B-minor scale... Or you can create your own. My friend Kahl (Monticone) who plays guitar created his own scales that he finds helpful to select from when he prepares to improvise.(iii) The point made about "melodic lines made by clusters" is defined by the delimited meaning of "scale" that Crispell describes in the next point:

3. Use of scales created from harmonic blocks to form melodies (i.e., the possibility of seeing harmonic blocks as scale fragments)

The concept of "creating scales from harmonic blocks" shows how scales can be a momentary grouping of notes within an actual improvisation (demonstration on piano). It's a reductive technique that you can break up harmonic blocks into single notes to work with, any harmonic block into any break up of notes. We're used to thinking about this the other way around, where harmonies are created out of predefined singular scale degrees.

For example, from a clusteral, serial-like harmonic approach a scale can be defined as emphasizing the lowest and highest notes of the cluster as dominants, and giving them greater accent. Then, notes in between them can be treated with a variety of dynamic degrees to differentiate their roles in your "scale" (demonstration on piano).

Personally, I find this way of discussing this approach very complicated and prefer not to think of anything as "scales," but prefer to think of it as different intensities of what's available at a given time that simply feel right to play.

(iv) while the differentiation between "abrupt/contrasting" and "continuous/evolving" may seem very obvious, you know, like a sharp, rhythmic attack (slams piano lid down) as opposed to a long-held sound, say, like the ambient whirring of the air conditioning in this room. So, even though this differentiation may seem very obvious, when the point is made in relation to what Crispell means by harmony, that is, from a perception aiming toward continuous sound and not from a systematic understanding of music, then the differentiation between these two kinds of approaches must be examined as both being contained within the continuous/evolving approach.First, we'll look at the main features of these. It could be said that a contrasting approach has more elements of surprise, more intense and pronounced "stand-out" gestures, more amounts of different information or motives packed within shorter amounts of time. Rather than elaborating upon one motif over a period of time, perhaps ten different motifs are stated as gestures without development--you wouldn't even think of them as motifs.

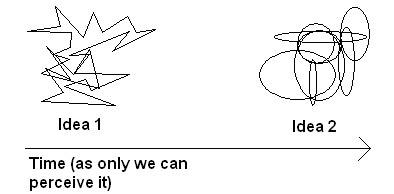

This is generally saying: One fixed idea to another fixed idea without evolution from one to the next:

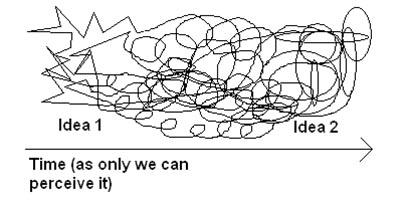

An evolving approach, on the other hand, is developmental. Idea 1 to Idea 2 are merged through development from one to the next.

The word "continuous" that Crispell uses in contrast to "abrupt/contrasting" does not mean that abrupt/contrasting should be understood as "discontinuous." In the process of improvising, it is very important that both approaches are understood in a continuous fashion.

Why? Here is where we begin to delve into notions of movement and energy in the process of acting out an improvisation; that even when you are playing sudden changes from one thing to another, they should be approached with an implicated feeling of continuity. It's that undefinable thing in music that we try to define as the "groove," the "flow," the "zone," or whatever, where you essentially merge with movement and accordingly operate upon continuously fluctuating degrees of energy flow.

We call this an "abstract" notion simply because this arena of operation, where movement continuously fluctuates, cannot be described as some measurement, in notes and staves, and we can only receive some kind of apprehension of it at the time of merging with it, and afterwards, in the impression that it leaves on us.

So what does it mean to have an abrupt/contrasting approach within a continuous approach? It means that, internally, you constantly force yourself into the field of movement so that you merge with it. You may be playing sudden changes from one thing to another, but you always approach these with an implicated continuity. So from the exterior, it may seem like a change of gestures are two separate discontinuous entities, but you make these two somehow connect via keeping a constant internal movement going.

Think of, say, a golfer swinging his nine-iron to hit a golf ball. The contact point between the club and the ball is just one element of a greater envelope that must be concentrated on throughout for the most effective hit. If this focus on the continuity of the stroke isn't made, then the golf ball isn't going to go anywhere.

But in order to make an improvisation work in such a way, it may help to consider what we're doing as dealing with energy fields in space where being able to perceive intervals separated from each other by attacking moments gives us the sensation of time. This is why Crispell, early in the article, stated: "Beginning with an interval (the most primal musical relationship)."

So in the field of action, we are generally saying that timing is everything. We're not talking about "tempo" or "keeping in time" as it's generally thought, or rather, we extend these concepts to include everything within them.

Okay, that's another abstract sounding comment that may make what I'm saying sound more complex than it actually is, so here's an example:

It's like driving a car. The speed at which you drive is never one set speed, say, if you're going eighty kilometres an hour, you're not actually going eighty kilometres an hour, but eighty kilometres an hour is a general level you try to keep to in accordance with the road rules and the other cars on the road. The car's speed is always fluctuating in very small degrees around this eighty kilometres an hour mark, slightly accelerating and slightly decelerating constantly--and if the car in front of you whacks on the brakes, without thinking, you also hit the brakes.

So, at some level, you're always in a state of acceleration and deceleration, this being a principle of movement. Whether you are playing upon a set tempo and you have a continuous focus upon the phrasing of a single line that accelerates and decelerates in timbral and dynamic degrees, or whether you are playing not upon a beats-per-minute base and the whole gamut of your material disposals are in an accelerating and decelerating flux--this is simply what is happening in movement, and being aware of it allows you to focus upon whatever lines of acceleration or deceleration you want to focus upon at any given time to enter into the "groove," or "zone," or whatever.

An explanation of timing given by martial artist Joe Maffei actually explains the fundamentals of a continuous, implicated approach to timing. He says (demonstrating each point as its being said):

- a beat is any time you make contact

- timing is the interval between contacts

- rhythm is repeated contact

- broken rhythm is the repeated starting and stopping of contact at irregular intervals

- speed is nothing more than perfect timing and rhythm--the most economical motion and the right technique delivered at the right range

The examples of martial arts and driving a car relate to a survival instinct in us that forces people to maintain continuous awareness, either in a spar or on the road, for the best reaction time and effectiveness, or, the most "perfect speed" possible, according to Maffei.

We can see from Maffei's summary of aspects of our perception of time into speed how it explains the process of building up your material disposals--techniques of combination and development--in order to train ourselves for an instinctive flow where we aim for "perfect timing and rhythm." Where he states that speed is "the most economical motion and the right technique delivered at the right range," it simply means an approach to improvisation where a trained knowledge and technical base is only there to serve the performing situation, where your material junk piles are thrown into a momentary composition. Crispell describes this as follows:

The development of a motive should be done in a logical, organic way, not haphazardly (improvisation as spontaneous composition)--not, however, in a preconceived way--rather in a way based on intuition enriched with knowledge (from all the study, playing, listening, exposure to various musical styles, etc., that have occurred through a lifetime--including all life experiences); the result is a personal musical vocabularyHere we can summarize the point about improvisation as being part of an equal blend with performance and composition. Practicing for such a situation involves a mixture of listening, reading, writing, analysis of recordings, analysis of scores, awareness of sound environments, technical practice both of compositional writing and of performance techniques, analysis of music both by theoretical reductions and by practical performing applications such as memorization and/or sight reading, experimenting in countless amounts of ways, and also--something very important if you want to actually perform--jamming with other musicians and setting up gigs once you feel ready.

I didn't delve into the full extent of what could be available for discussion on the material aspect to give a bit of room to discuss some of the movement aspects; and it's tough bringing the momentary aspects of improvisation into a descriptive form, but I spent some time on them because even though they may seem a bit confusing for now, I have found research into that area of practice a lot more helpful and fulfilling in terms of improvising than the material aspects. The end goal of improvisation, as with all music, is pleasure, receiving pleasure, and that law of diminishing returns related to our nature of receiving pleasure--where we constantly seek more pleasure, different pleasure, to what we have already, since the pleasure once received diminishes in value--has led us into this stage of coming up with all these sorts of ideas to receive pleasure from music. So enjoy!