GREG KOT

Kot in his office, 2017

Chicago music scribe looks back

Interview by Jason Gross

(August 2020)

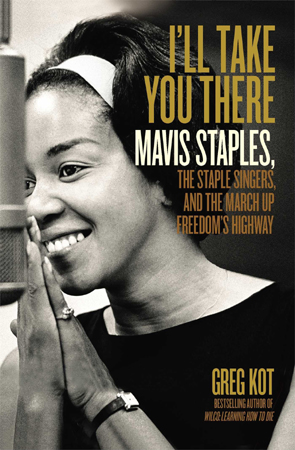

For my last SXSW in 2019 (which better not be THE last SXSW), I got to meet someone there that I wouldn't see there again, and not just because of the COVID scattering of us all. Greg Kot had been the music writer for Chicago Tribune since the beginning of the '90's, along with being co-host (with Jim DeRogatis) of the popular, beloved Sound Opinions program and the author of, among other tomes, biographies on Chi-town legends Mavis Staples/The Staple Singers (I'll Take You There- see excerpt here) and Wilco (Learning How To Die). That's not even mentioning bylines he's had with Rolling Stone, Entertainment Weekly, Vibe and many other places. Impressive as all of that was, that wasn't why I wanted to meet up with him again. Sure, he's a hell of a nice guy and a music nut, which isn't always an easy combo to pull off, but even after writing for decades and through the turmoil of the music biz and writing biz, he still had a genuine, infectious enthusiasm for his job and the music he covered. But that would change this year as his publication went through its own turmoil of buyouts and change of ownership. Kot decided to hang up his virtual pen at The Tribune, which is a shame and a loss to us music fans also. I asked him to do an ‘exit interview' but he's not retiring- he continues to do Sound Opinions and he's working on yet another book.

PSF: Which music writers really enchanted you before you started writing?

GK: Reading the album reviews circa 1976-82 in Rolling Stone, Musician and the Village Voice led me to voices such as Greil Marcus, Janet Maslin, Tom Carson, Dave Marsh, Lester Bangs and a few others who shaped my thinking and cost me hundreds of dollars in album purchases. I don't think I regretted a single one. Half my collection during this time was of albums that I hadn't heard, only read about. I didn't consciously realize it at the time, but the thought that something I read could induce me to spend money on a piece of music must have registered: music writing could be powerful stuff.

The best of these reviews brought a socio-cultural perspective that put the music in context and enriched its meaning - at least for me. Marcus' books were just as crucial: Mystery Train was ostensibly a "music book," an underappreciated species of nonfiction when first published in 1975. But it read like literature in the way it placed the work of artists as diverse as Sly Stone, Randy Newman, Elvis and the Band in a broader framework and wove a kind of story about America, one that linked generations and led to a deeper understanding of the cultural and political forces at play that made such music resonate. Mystery Train affirmed the notion that rock/pop speaks with greater immediacy than any other art form about who we are and where we are as a society.

Marcus' Stranded was just a blast to read: a bunch of my favorite writers - Robert Christgau, Ellen Willis, et al - making the case for their favorite albums. I poured over Greil's personal discography that served as the book's epilogue, and built a good deal of my album collection based on what he wrote.

Robert Palmer (the former New York Times critic, not the singer) demonstrated a way to communicate deep musical knowledge without resorting to technical lingo; his masterpieces include Deep Blues and his 1978 Muddy Waters profile for Rolling Stone. The Muddy piece was just so profound, at once deeply reported and analytically revelatory. Nelson George wrote from a personal, but never solipsistic, vantage point, about soul and R&B.

Christgau's "Consumer Guide" influenced the format of countless record-review sections, including the one I helped create for the Chicago Tribune. The Dean's format could be copied, but his pithy humor, sometimes impenetrable, often provocative insights and voracious, genre-leaping curiosity were one of a kind. I loved the way Ira Robbins (Trouser Press) and Jack Rabid (The Big Takeover) turned their mimeographed fanzines into must-reads, brimming with sharp observations about important bands and artists the bigger media outlets overlooked. And my predecessor at the Tribune, Lynn Van Matre - a pioneering female critic - covered the scene with a discerning, skeptical ear.

PSF: How did you yourself figure that you wanted to be a writer also?

GK: Writing became a mission when I was about 12 years old. I read newspapers as a kid - mostly the sports section - and imagined myself writing about my favorite teams in a daily newspaper. But as my interests widened, so did my reading list. I was neck deep in the Beats and the new journalism of Tom Wolfe, Norman Mailer, Hunter Thompson, Mike Royko, etc.. I started reading reviews in Rolling Stone and Greil Marcus' Mystery Train, and that flipped the switch. When I'm stuck while writing, I'll stop and start reading, preferably something inspiring. Reading well has always motivated me to try to write well.

PSF: Could you talk about your writing pre-Tribune?

GK: At Marquette University, I held various editing positions at the student newspaper, and ended up covering a bunch of shows in Milwaukee for the counter-culture weekly, the Milwaukee Bugle-American. Despite the decidedly uncool-sounding name, the Bugle-American gave me the latitude to cover a wide range of artists and to write about them at length, even though I was ill-equipped for the job. The patience and guidance of my editor, Gary Peterson, helped iron out some of the rough spots in my thinking and writing. After graduating, I was hired as a copy editor at the Quad-City Times in Davenport, Iowa, and volunteered to write a weekly music column. Free records from the record labels! I had it made. I got hired by the Chicago Tribune as a copy editor at age 23 and started a couple of fanzines with my friends that allowed me to write during off-hours. We were dishing about art and culture, with enough insight and irreverence that we earned a spot on some magazine shelves at book stores in Chicago. Even though I wasn't being paid to be a writer for most of the '80's, I was nonetheless writing every day, and that helped when the Tribune hired me as rock critic.

PSF: What was the Tribune like when you started working there?

GK: I started working there in 1980, and was named the rock critic in 1990. So I had 10 years in the newsroom working as an editor with metro and national reporters, and then later with the features staff. The place had plenty of characters who slammed phones, shouted instructions, smoked and drank beer lunches at the Billy Goat pub. I got to spend time with some legendary figures in Chicago journalism, both at work and after hours. Mike Royko was the biggest name, but they were all larger-than-life characters in my eyes: Gary Dretzka, Neil Mehler, Denise Joyce, Rick Kogan, Ross Werland, Geoff Brown, Terry Armour, Paul Sullivan, Achy Obejas, Richard Christianson. Once I became the rock critic, my editors gave me a lot of room to define the job, to cover stories and styles of music that the paper had not covered previously. My first few months on the job I wrote cover stories for the Sunday Arts and Entertainment section on Frankie Knuckles and house music, the rise of Wax Trax Records and an in-depth profile of Public Enemy.

PSF: You've worked with DeRogatis for a while now. How did you find you complement each other with the program you do together? Do you see that you both learn from each other?

GK: We may not agree on a lot of music, but we do share certain ideas about the role of criticism. The show would've ended after two or three months if we'd basically agreed on most things, or pretended to be the last word on whatever it was we were arguing about. We always viewed the show as a conversation starter, with the listener as the third person on the couch as a participant. There's a reason the listeners get the last word on the show with five minutes of call-in messages. We're journalists and writers, not radio professionals, and we don't pretend to be, so by default, we can't be anything but who we are in "real life": music nerds. Jim and I never know what the other guy is going to say in advance, so what you're hearing is a fairly spontaneous interaction about whatever music we're reviewing that week. Even when Jim and I agree on a piece of music, it's usually for different reasons. When we disagree, the arguments carry on for years - I love early Springsteen, Jim hates all Springsteen to the point of arguing that he's a lesser songwriter than Meat Loaf; Jim loves Genesis, my tolerance for all things Genesis-related essentially encompasses "Carpet Crawlers" and Peter Gabriel's solo career. I love golden-age hip-hop, soul and funk, Jim can listen to all things punk all day and night. The key to the show's longevity is that we believe our favorite record is the one we're going to hear next week. We're most enthused when we discover something new to rave about.

PSF: You had mentioned a while ago that you were especially proud of an article you did where Bono followed up with you about something you wrote. Why in particular did that stand out for you?

GK: I don't know if I'm more proud of that article than a bunch of others I could cite, but it is one of those pieces that resonated with a lot of people, I suppose because of U2's stature at the time as one of the biggest bands in the world. More than 15 years after it appeared, I still hear about it. It came about because I wrote a piece earlier in the year (2005) that called out U2 for a variety of missteps, most dubiously bungling a fan-club ticket sale for their upcoming tour. For a time, I respected U2 for how they reshaped what an arena show could be, but, I wrote, "In recent years, their business practices have become more suspect, their attention-seeking more transparent, their principles more readily compromised, and their music less challenging." That earned me an angry phone call from Bono. It began: "There's a dark cloud over us, Greg..." and went downhill from there. He wanted to talk off-the-record when the band showed up to play shows on Chicago that spring. I insisted that it be on the record, and that he address all the issues I brought up in the article. He ultimately agreed, and the resulting piece was a rare instance of major rock-star interview that had nothing to do with promoting a product or pimping a tour. Instead, it was a pretty frank discussion about the art/commerce divide and how a big, increasingly corporate rock band tried to meet the challenge of staying relevant.

PSF: OK, so now I'm curious about other articles that you were especially proud of and what was it about them that stood out for you.

GK: In my first few weeks as the Chicago Tribune rock critic, I took the opportunity to cover subjects that I felt had been relatively neglected in the paper's Arts section, including house music. I interviewed Frankie Knuckles for a major cover story on the rise and influence of Chicago house music that included all the innovators: Ron Hardy, Farley Jackmaster Funk, Marshall Jefferson. Tracking all those guys down wasn't easy, but I was proud that we are able to get all those guys on the record on the revolution they started.

In 1993, I got invited to Ice-T's home at the time of the "Cop Killer" controversy, when he was booted off Warner Bros. records. The interview took most of the day and in the evening, I remember him looking down onto his old neighborhood of South Central from his living-room window in the Hollywood Hills - it was one of those moments that made a writer's job feel like a gift.

I also had the privilege of interviewing Prince on four separate occasions. With each interview there was a little more trust, and a little more willingness to open himself up. The last time he invited me to watch him rehearse his band at Paisley Park - I thought this must be what watching Ellington or Basie or James Brown up close must've been like, putting these first-rate musicians through their paces as he constantly critiqued, refined and reinvented his music. Then he got teary-eyed showing me the letters that he exchanged with Mavis Staples when he was working with her in the '90's, and how her words sustained him.

PSF: Regarding your Mavis Staples and Wilco books, did your understanding of each of them change at all after you did all of your legwork?

GK: I went into each book as a journalist with the notion that there was a fascinating, book-length story to be told about the subject, and I'd follow the truth wherever it led. Beyond that, there were no preconceived notions. The books were all written with the understanding that the subjects wouldn't get to read the book until it was published, the same ground rules that applied when I would write an article for the newspaper. I felt there was a bigger story in each beyond connecting the biographical dots or chronicling the recordings.

In the case of Wilco, I aimed to frame the band in the context of a music industry as it was reluctantly transitioning from the 20th Century monopoly dominated by major labels and a handful of radio conglomerates into what was at first a rogue digital economy. That necessitated a deeper look into the dynamics not just of the band, but its relationship with the broader industry and culture that consumed its music. Along the way, I wanted to tell the story of how the band itself navigated this uncharted terrain, for better and sometimes worse. I realized I was writing not just a story about how the "industry" did or didn't work, but how a band relates to one another in times of crisis. All the key players were willing to talk, but that doesn't mean their stories were the same. Five people could be in a room when some pivotal moment occurred and each would have their own version of that event - not because they were exaggerating or lying, but because they just remembered it differently. A detail that seared one memory might have meant nothing to the person standing a few feet away from them. As much as these people shared a history, there were also things unspoken between them, mysteries left unexplored.

When the book was published, there were a few bruised feelings. Each had their own version of the story they would've wanted to tell, and mine wasn't necessarily it. But I think they all felt the account in the book was true. One of the Wilco band members told me afterward that they all learned things about each other after reading the book.

With the Mavis Staples/Staple Singers book, I had long thought that this group deserved a book that put into context the family's role not just as artists, but as activists who helped provide the soundtrack for the civil rights movement, along with peers and friends such as Curtis Mayfield and Sam Cooke. Everybody knew about their Stax hits in the '70's and their work with the Band in The Last Waltz, but the rest of the story was pretty hazy. Mavis had always been an affable interviewee, but in general, she repeated many of the same anecdotes and stories in all her interviews in response to the same boilerplate questions. I felt there was a lot more to her story than she was willing or prompted to reveal. I had known and written about the family for decades, and when I approached Mavis about writing a book, she was reluctant at first. She told me she had turned down other offers. But I think because she was approaching her 80's, she started to feel a certain urgency to make sure her family's story was shared in greater depth.

The second obstacle was finding someone to publish it. The New York publishers who wanted a follow-up to the Wilco book barely knew who Mavis was circa 2005 - an indication of just how far off the cultural radar the Staple Singers had fallen. But within a few years, Mavis had resurrected her career post-Staple Singers with a series of great solo albums, concerts and TV appearances.

We got to work in 2011, and the interviews were incredible - we'd go for four, five hours at a time in Mavis' living room. I also was determined to dig into the role of her father, Roebuck "Pops" Staples, as a musical innovator, fusing blues guitar with gospel harmonies. But what was lacking was a deep accounting of Pops' upbringing in the Deep South, his life on Dockery Farm in Mississippi circa 1915-1935 (Mavis and her siblings all grew up in Chicago, after Pops and his wife, Oceola Ware, moved north). I didn't know how I would tell that story, short of conjuring Pops and some of his late collaborators, friends and family with a Ouija board. Then I got a call from Mavis one night: "I think my dad was working on a book when he died, but I don't where it is." Mavis finally tracked it down, in the closet of her sister's condo, and it was everything I hoped it would be—an accounting of Pops' young life, including his first memory as a child: His mother's funeral. Pops' unpublished memoir encompassed several hundred pages, half of which bore witness to his life as a sharecropper's son, would-be blues guitarist, boxer and rambling spirit in Mississippi, eager to flee the farm for the promise of a job, any job, in Chicago, a city he'd only heard about in blues songs. The unexpected find turned the book around. Mavis, it turned out, was the gift that just kept on giving.

PSF: I was always impressed with how much you cared about the Chicago music scene and its survival. Obviously now, it's going to be especially tough. What do you think will be the key to help it rebound?

GK: Chicago's creative community is well-seasoned at surviving and figuring out how to thrive under adverse conditions. The city's scene was always an afterthought on a national or international level because there was very little corporate music-industry infrastructure in Chicago. City Hall treated the music scene as a nuisance: big rock and soul concerts were essentially banned on the lakefront for decades, and ordinances were passed that made live music at clubs a bureaucratic nightmare. Yet the resilience of the indie scene - record labels, clubs, booking agents, bands and artists - was key to a steady stream of innovation: house and industrial music were born here in the '80's, noise-rock and post-rock flourished, unconventional artists such as Kanye West and Chance the Rapper became stars. At a time when massive corporations swing the biggest financial stick in City Hall, the city's club scene is one of the primary reasons that young people come to Chicago to live and play. It's also a hugely proficient if under-recognized economic engine. A University of Chicago study once called it "a music city in hiding," but we finally have a mayor in Lori Lightfoot who seems to appreciate the value of this cultural resource. Like other scenes across the country, the survival of clubs and independent music in Chicago is threatened by the COVID-19 shutdown. But the way the city works (or doesn't work) through the decades has made resilience and self-sufficiency a necessity for any band doing business in Chicago. I hear new music by do-it-yourselfers such as Melkbelly, Jamila Woods, Ohmme, Beach Bunny, Nnamdi, Whitney, Twin Peaks and Peter CottonTale.

PSF: When I met you at SXSW 2019, you acknowledged how terrible the news biz was then but you sounded like you still had enthusiasm for your work. What kept you going for so long?

GK: Despite all the amputations, to paraphrase Lou Reed, I could still listen to and write about the music I loved in the way I wanted. My editors gave me the latitude to decide what artists and stories to cover and how, and that never really changed over my 30 years at the Tribune's music critic. It was always a one-person beat; unlike other major dailies such as the LA Times or the NY Times, the Trib did not have a staff of writers covering popular music. So I was essentially a one-man department, and I recruited and in many cases mentored, a wide range of freelancers who helped complete our coverage: Chrissie Dickinson, Josh Klein, Andy Downing, Bob Gendron and many more terrific writers. Though the Tribune's ownership made soul-crushing decisions over the last 15 years and cost many fine journalists their livelihoods, the staff continued to produce excellent work. I felt proud to be a part of that team. My enthusiasm for the work I was privileged to do never waned. But I also was determined to leave the job on my own terms when the time came. With a hedge fund poised to take over the paper this year, that time was now.

PSF: In your previous answer, you quoted the Velvet Underground and in one of your website pics, you show off a Velvets chair you have. What is it in particular about their work that affected you?

GK: I got to the Velvets late. I was 18, 19 years old when I heard Live 1969 circa 1975, and it prompted me to re-evaluate pretty much everything I knew about music to that point (which wasn't much, but I digress). The way Reed and his bandmates married melody and noise, the vulnerability in the ballads, the deceptive simplicity and directness of the songs, the way the band locked into a hypnotic groove like "What Goes On" and you never wanted it to end. To me, it's still a perfect album, and revealed this secret thread of rock history (at least it was a secret to me) that connected to the musical currency of my college years: Ramones, Patti Smith, Talking Heads, etc..

Eventually, I tracked down all the Velvets' studio albums, and each felt like a distinct entity, the same band revealing a different side of itself, like the chapters in a great novel. What became apparent was that Reed wasn't writing and singing about drugs, drag queens, gay people, outsiders on the Velvets albums for shock value, but in a way that seemed matter of fact, at times brutally honest, but somehow empathetic. A song like "Candy Says," it just bowled me over when I first heard it, about this person who hated her body "and all that it requires in this world." It spoke for every one of us that at one time or another felt insecure or inadequate-- basically, all of us. I had an African-American roommate at the time who introduced me to so much music and culture outside my frame of reference that I still think about him to this day. But he left school one Thanksgiving and never came back. Two of my best friends at the time confided to me that they were gay. I got only a small glimpse of the pain they were in, but it was life-altering. I think Lou Reed's music was for them, and by extension, any human being struggling to find his or her place in the world. What's it like to live in a world where you can never measure up to the standards set by the people who made the rules? That's what Lou Reed's music was about.

PSF: Related to DeRogatis' long-standing R. Kelly pieces, the recent Michael Jackson documentary and other high profile media revelations, what are your thoughts about 'cancel culture'? In your mind, are there certain criteria and individualized ways to approach this?

GK: Who is appointed judge and jury when determining what is objectionable or offensive behavior? One of the foundational elements of journalism in a free-press society is that we don't live in a black and white world. Each case is different, and should be evaluated on its merits. At the same time, we have to acknowledge that we live in a capitalist society, where a corporation can pretty much get away with anything so long as shareholders are making a profit. They need to be held accountable. Hundreds, if not thousands, of people in the music industry have benefited over the decades by enabling reprehensible individuals who happened to make hit records. In particular, it's beyond disturbing that record companies, concert promoters and radio stations continued to profit from R. Kelly's music even as evidence continued to mount that he belonged in prison. Consumers who spoke with their wallets ultimately led to Kelly losing his label deal and concert bookings. Social media has opened up the opportunity for the disenfranchised to speak truth to power, and that's a healthy development. But #cancelRKelly wouldn't have had a much impact were it not for Dero's two decades of reporting. In a society founded on free speech, the truth ultimately won out. At its best, cancel culture can amplify inconvenient truths. At its worst, it can be a form of mob rule. Either way, it's no substitute for what journalism can and should do.

PSF: After the Tribune, what kind of any writing (or non-writing) projects planned for now?

GK: I'm working on a music-related memoir right now. I hesitate to say too much about it at this point, but I'm excited about it. I love writing and I love music. Those two things have been central to my life since I was about 12 years old. That isn't going to change anytime soon.

PSF: This is a tough thing to talk about but with the already deteriorating state of the media, compounded by the pandemic, what are your thoughts about the future of US journalism?

GK: The last few years have affirmed the need for and value of great journalism. When smart people invest in journalism, the results speak for themselves: Look at the record breaking subscriptions to the New York Times, or the growth of the Washington Post. It's not surprising. A democracy depends on an informed citizenry to thrive. Without it, we're driving blind. For that reason, journalism will always exist in some form. The real question is, what's the future of critical thinking? Will consumers be educated or savvy enough to discern credible news sources from agenda-driven propaganda outlets?

PSF: Related to that, what do you see as the future specifically for the Tribune?

GK: I hope for the best. I'm so proud of the work my colleagues have been doing at the Chicago Tribune under trying conditions over the last 15 years. Imagine if those journalists were working for a publisher who actually invested in their work and made sure they had everything they needed to get the job done to the best of their abilities. Even though I left the paper four months ago, I remain a subscriber and I think about the necessity of the Tribune as a watchdog in one of the biggest cities in the world. Trib reporters, photographers and columnists continue to break stories every day that the city needs to be its best. Unfortunately, the hedge fund that is about to take over the Tribune has different priorities. It's not an unwinnable fight. I can't imagine the city without its largest daily newspaper, but maybe that's only because the alternative is too chilling to consider.