HAIR TODAY, GONE TOMORROW:

|

|

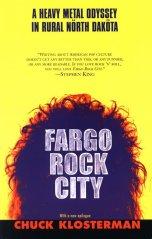

Chuck Klosterman's Fargo Rock City

As experienced by Marc Horton (January 2003)

I've always been slightly ashamed of the irrevocable

fact of my heavy metal adolescence. The closet has

been purged of all vestiges of those halcyon days (the

Queensryche T-shirts, the denim jacket with "Megadeth"

etched fastidiously in magic marker on the back). My

musical tastes have veered, often schizophrenically,

in every direction AWAY from anything with so much as

even a guitar solo in it, as a reaction to those

years. Despite all this, I have lived in acute fear

of certain facts from my past coming to light in the

company of those who would attempt to use it to ill

ends. Those years of paranoia and darkness, however,

have come to an end, thanks to Fargo Rock City. Hallelujah- I have learned to embrace my heavy metal past.Flashback. 1986, the summer before 6th grade. My family moves to South Georgia swampland after a childhood of quasi-military-brat transience abroad. My neighbor, Brian Brown, plays me Twisted Sister, Cinderella and Motley Crue cassettes, and I come to understand that in America, it is not cool to listen to the same music that the adults in your family listen to: my Lionel Richie and Boney M tapes were history. We spend evenings creating a pirate radio station of sorts. With one boombox, we are DJ's, listening to our favorite cuts from the above bands as well as making up skits and fake ads with all the pith and passion that our 12-year old hearts could summon. And on the other boombox, we record the whole durned mess. I had not thought of this particular episode in many a moon, but after reading Fargo Rock City, I was scrambling around in the basement at the old place, trying to find one of the handful of tapes we recorded that summer. As I look at my CD's and records from where I sit now, I'm trying to think of the last time the simple act of listening to music brought me such unadulterated joy, liberated from the fear of being judged by my peers. The times are few, and they are, as they say, far in between.

Now, I understand full well that a book about the history and culture of hair metal is going to be a tough sell. Never has a genre been more readily dismissed out of hand than that period and style from the mid-80's to the early-90's, when sleek dinosaurs like Poison and Guns N'Roses stalked the charts and airwaves. But Klosterman has done the unthinkable by producing an intelligent, very funny, and most dangerous of all, completely accurate observation of what it meant (he will show you that it DID mean something to a great many of us) to be a fan of hair metal.

In the guise of a memoir about growing up in "rural North Dakota"--as opposed to "urban North Dakota?"-- Klosterman has captured the essence of music as an experience, a place to go outside of your own particularly uncool reality, where Kiss lyrics serve as moral guideposts in times of emotional and financial ruin, where a slow dance with your 10th-grade crush punctures the time/space continuum, where a Lita Ford cassette rescues you from the banalities of basketball camp.

(One of the most prized objects that I own, I must confess, is a letter I once received from Eric Carr, the drummer who replaced Peter Criss in the makeup-less Kiss of the '80's, after writing to the Kiss Army. His advice to me, to "keep rockin', drummer guy," proved to be nothing less than totally inspirational throughout the years, despite my never having actually taken up the drums, as I had said I hoped to in the letter. I remember being stuck in traffic, and very downhearted, when I heard on the radio that both he and Freddie Mercury had died on the same day.)

Klosterman is at his funniest and feistiest however when it comes to the details, and God help him, he demonstrates an almost encyclopedic knowledge of the historical minutiae of the hair metal phenomenon as well the attendant pedantic and semantic issues. My only criticism of the book--and it's not much of one--is that there is no index, which makes finding that particular ridiculous bit about the Crue, or that other hilarious quote from Alice Cooper, a task. And it only became a task for me because I couldn't help but try to make everyone I knew read the damn book. But luckily for the reader, the gems are practically on every page. Of course, the issue of why Van Halen was a glam rock band (and Def Leppard was NOT) and not just another rock 'n' roll band is handled with aplomb:

"...listening to Clapton is like getting a sensual massage from a woman you've loved for the past ten years; listening to Van Halen is like having the best sex of your life with three foxy nursing students you met at a Tastee Freez."

Also, the table listing non-metal songs that were decidedly cool enough be enjoyed by those within the glam rock subculture, and the reasons for their popularity, is a revelation: "Going Back to Cali," by LL Cool J, for example, was allowed because "somebody saw the video and wouldn't shut up about it." "So Alive," by Love & Rockets, made the cut by virtue of its being "introduced by nondescript 'cool kid' from neighboring town." His scope extends to the larger picture, as well. As to the contention that the music of Judas Priest convinced two Nevada teens to kill themselves, Klosterman offers, "I listened to (the album in question) Stained Class, in 1985, at a friend's house, and that didn't even convince me to buy the goddamn record."

He makes a valid case, ultimately, against the stigmatization of hair metal as 'stupid,' by measuring that argument against the other pervasive criticism, that it's offensive because it's 'sexist'; surely, they can't be both, he asks, because if it's not art, then it can't be offensive (i.e. it can't matter, or have any sort of real effect). Besides, if you were 20 or younger, and you weren't listening to Poison or Guns N'Roses in 1988, you were probably listening to Rick Astley or Milli Vanilli. Give or take a couple of goth kids, that is. Isn't that more unforgivable?

It's easy to forget, in the years since Nirvana drove the last nail into the coffin of hair metal how popular the stuff was. Even if you've never made out to Warrant in the cab of a Chevy truck, it would be hard to dispute his claim that "if your first experience with finger-banging took place between August of 1989 and March of 1990, it probably happened while you were listening to 'Heaven'." As for me, I saw a pair of female breasts for the first time at a Kiss show in 1989, at which the entire front row was made up of women who, I remember thinking, seemed to like the band even more than I did. I may not have known (or cared) at the time, whether the breasts were real but I suppose I want to believe that my heavy metal experience was.

At first, I was taken by how much Klosterman's experience seemed to mirror my own, in the sort of way that those boys crying at Morrissey concerts seem to feel that every word he sang was coming straight from their own lives. After all, I went to basketball camp too. And I also have never heard the Tygers of Pan Tang, supposed seminal New Wave of British Heavy Metal band; I, like Chuck, never had long hair but longed for the power which it seemed to grant. Now, the more I think about it, I'm just pissed that I didn't write the book. Damn you, Chuck Klosterman. Damn you to hell.