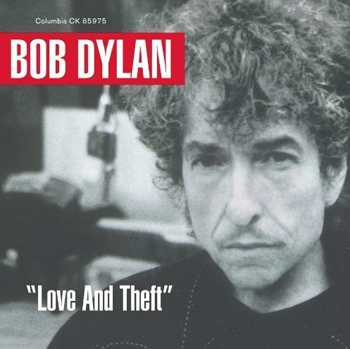

Dylan's 'Love and Theft'

by Kevin Cenedella

(February 2012)

I remember the night I bought Bob Dylans "Love and Theft". My friend and I had driven to Blacksburg, Virginia from our small college in Radford. It was a Monday night. This particular store stayed open after midnight on Mondays so you didn't have to wait until the next morning to buy new releases. As we drove home, I listened to the first three or four tracks and remember not being overly impressed. I had taken the drive with high expectations as Rolling Stone had given the album five stars. I went home and went to sleep. I woke up the next morning to a cool late summer day. You can feel the changing of the seasons early in the mountains. I walked to class but it was cancelled. It was September 11th 2001.

Of course, Bob Dylan is no psychic. Like the rest of us, he had no way of knowing what that Tuesday had in store for the nation. Obviously, that tragic event haunted me for the next several months. By sheer coincidence, "Love and Theft" became my soundtrack for that particular period. I listened to it as I thought about the randomness and cruelty of the world. In the weeks following, I also reflected upon the kindness and unity a national tragedy can bring. Maybe the albumís release date is why it has resonated with me over the years. But in the material itself, you can recognize the duality of mans character. In it there is chaos, destruction, despair, judgment, and hope for redemption. Those were all things I thought about deeply on that Tuesday. I know Dylan had thought about them too, and obviously longer than me.

I see "Love and Theft" as Dylan's most intriguing album. Dylan has always been a character of shifting shapes. When fans had him pegged as folk singer, he quickly turned to rock, causing great anger among his fans. After he conquered the world with rock at its highest form with albums like Blonde on Blonde, he surprised everyone again by switching to down home, almost lazy country music. He was the person probably most responsible for the hippie movement. Yet when it was unfolding before the worldís eyes, he was living a life seclusion in Woodstock, trying to quietly raise a family. He refused to be a figurehead, moral leader, or endorse any cause. When the fabled Woodstock happened, he had already packed up and moved away until the ruckus blew over. He was always one step ahead. This evasive dance went on for decades. Eventually it culminated in Dylan, born Jewish, converting to Christianity and then trying to convert fans. Once you figured you had him figured out, he was already another person in another place. Grasping Dylan is like trying to grasp vapor.

To understand "Love and Theft", it is important to realize Dylanís history, starting with the folk scene of the early sixties. Folk music was not merely seen as music, but as a means for changing the world. Dylan was the king of this scene. His songs were socially conscious and questioned authority and the current social order of things. He was the champion of the underdog and was seen as somehow above wanting fame or material things. This was the beginning of the myth of Dylan. For some people, he was seen as more than a musician. He was upheld as a sort poster boy for civil rights and the peace movements. This is the Dylan that is stuck in time. This is the ideal Dylan that people of that time want to see.

The fact that Dylan spent years trying to destroy these myths about himself doesnít seem to matter. He is speaking to the deaf. The classic folk anthems he wrote ("Blowiní in the Wind," "Masters of War") were sung by him in such an earnest manner that when he changed styles, people wondered if he was out of his mind or even joking. That material was so serious that the rejection of it had serious consequences. When he "went electric," there was even the possibility of violence in the air. After all, Dylan represented people who were going to change the world by song! And Dylan was supposed to be the one singing these songs.

The "reinventions" of Dylan were not seen as such by him. Anyone willing to do any research on Dylan knows that he loves almost every kind of music. He always loved rock Ďn roll. Buddy Holly was his first idol and he even saw him in concert. . He spent his teenage years in Minnesota working on a mean Little Richard impression. Later, when he was already a star, his hands may have been focused on the serious task of folk music but his ears were constantly straying. He even loved the sugary sweet pop of people like Ricky Nelson. Knowing this would have caused his fans at the time to faint. This was not considered serious music. But, the idea of putting all of these kinds of music into neat little categories bothered Dylan. There was no "real" and "fake" to him- only music he liked and music he didnít.

On "Love and Theft", Dylan does not "reinvent" himself like he had done so many times before. What he warps is not so much his identity, but time itself. "Love and Theft" is an album rooted in the musical traditions of 100 years ago. It is rooted most prominently in the blues tradition. Dylan grew up listening to blues music and was enamored with Robert Johnson and Blind Willie McTell. Upon arriving in New York in 1960, Dylan played with and met and played with many famous blues players from the past (Lonnie Johnson, Big Joe Williams, etc). He also spun many romantic tales of playing with other mythical bluesman on his great journey from the Midwest to the big city.

Dylan's preoccupation with the blues should surprise no one. The blues shares many of the same traits as the folk music he was an adherent to. It is music of shared tradition. Many blues songs and or lyrics are so old, that it is impossible to trace their lineage. Whole songs or verses have been borrowed liberally throughout the history of the blues. Their provenance is not important. Also, it is impossible to know.

The importance of the blues lies in the fact that its origins predate commercialism or even recording. It is an art form that came about because of a need within people rather than a want. The blues was being sung on plantations throughout the South for many decades before it ever occurred to ANYONE that a penny could be made from it (or recorded music for that matter). It was sung just to help people cope. It is a kind of "everymanís" music that imminently relatable. It is sacred to some.

For this reason and others, the blues has largely resisted revolution. Sure, it eventually became electric on its winding path up the Mississippi to Chicago, but its structure of repeated lines and set time signatures is what makes the blues the blues in the first place. Over the years, this rigidity to a form has caused the blues to become standardized in the themes it dealt with as well. The name of the woman that left Son House in 1931, or what train Willie Brown left town on that same year have never been important. It should tell you something that Howlin Wolf may be the greatest blues artist ever, but you can count the songs he recorded in 40 years that weren't about a train or a sex on one hand. The details of the lyrics were never important. I listened to "Smokestack Lightning" hundreds of times before I even realized it was about a train. The feelings conveyed in the songs matter, not necessarily the lyrics themselves.

This is what makes ""Love and Theft"" so special. Dylan stretches the possibility of blues music as a form of narrative while somehow remaining true to its traditions. The songs are rich in imagery, biting in wit, and sometimes funny as hell. They are anything but formulaic and, maybe for the first time in the blues idiom, the lyrics are as important as the vibe. Dylan is elusive as ever. He is surely not singing as himself. Even if he is, it is a version of himself that he has placed far back in time.

In the first edition of his autobiography Chronicles Dylan recounts how he used to spend hours everyday in the New York City public library reading newspapers from the 1800's. He could become immersed in even the most mundane facts of another time and that manifested it self in his songs. This disorientation he learned to weave became is apparent on the famous "Basement Tapes" recordings he made with The Band in the summer of the 1967. It is also apparent on "Love and Theft". There are no living people in these songs. However, Dylan casually drops names like Big Joe Turner as if he was up drinking with him the night before. Dylan seems to place himself in the past in order to convey a foreboding that only someone who has witnessed a frightening future can know.

Upon reading that Dylan was going to pay homage to Charlie Patton on the song "High Water Everywhere (for Charlie Patton)," I was excited. I honestly expected a version faithful to the original which was about the great Mississippi flood of 1927. It is similar in that, even though Dylan is from Minnesota, he sings about the Mississippi Delta like it's his home. The song is filled with people Patton would have known and places he would have frequented. But Dylan's version is far more ominous. He seems to be singing about future events instead of those in the past:

High water risiní, six inches íbove my headOver drums doubling as thunderclaps, Dylan sings of familiar landmarks being swept away by tumult. The calamity leaves Big Joe Turner in Kansas City, "looking east and west from the dark room of his mind." He ends up on the corner of 12th and Vine (just like in the song "Kansas City" itself), but "thereís nothing standing there." Mr. Turner could just as easily be standing in Lower Manhattan, disoriented and lost without a visual compass. Dylan also hints at a larger destruction than the landscape. The destruction may even consume civilized society itself. In the most tantalizing verse Dylan sings:

Coffins droppiní in the street

Like balloons made out of lead

Water pouriní into Vicksburg, donít know what Iím goin' to do

"Donít reach out for me," she said

"Canít you see Iím drowniní too?"

Itís rough out there

High water everywhere

They got Charles Darwin trapped out there on Highway FiveHere Dylan seems to be alluding to a clash of civilizations. A figure of enlightened thought is being held hostage by nefarious forces. However, it's not just what Dylan says but how he says it that's so menacing. "I don't care" slips off the the judges tongue so easily. Dylan's delivery juxtaposing the seriousness of the threat with how easily it's expressed. It's as if the Judge gives the thought of extinguishing a human life no more thought than he would to stomping out a cigarette.

Judge says to the High Sheriff,

"I want him dead or alive

Either one, I donít care"

High water everywhere

On "Love and Theft", Dylan seems to relish in playing a commoner from the past that is down on his luck. The character from the song "Po Boy" is such a pathetic figure that it is almost funny. At every turn he is rejected, abused and taken advantage of and yet he seems grateful for even that kind of attention. His wifeís lover comes around openly. He pays local merchants more than the price of products even though heís not being extorted. On "Cry Awhile," he ticks off all he has done for his woman and laments that "all you gave me was a smile."

"Lonesome Day Blues" is the albumís hardest track. Dylan voice growls and snarls over driving guitar and drums. He recounts his blues and troubles as he races past landmarks. He is presumably rushing home to see his woman. His mind wanders and he despairingly admits, almost out of nowhere, that "I wish my mother was still alive." Again, here he is an inept man who canít keep his woman satisfied. On his journey, he has passed her other man. He ends the song with a couplet that both expresses foreboding and optimism. Optimism being a relative term here. Again, the world has taught him not to expect much:

Leaves are rustling in the wood, things are falling off the shelfHowever, Dylan seems to put a twist on the everyday man persona he adopts. The characters in these songs do not seem like they should be capable of thinking or saying the profound things they do. They are all sharp and quick-witted. They speak knowledgeably about the history of Western civilization. Don Pasquale, George Lewes, and Charles Darwin are all mentioned. Not coincidentally, these are all figures from the 1800ís. They dish out funny puns and speak in riddles. On "Sugar Baby," Dylan sings:

Youíre gonna need my help sweetheart, you canít make love all by yourself.

Some of these bootleggers, they make pretty good stuffThe key being the word "hide." Dylan's relationship with "Aunt Sally" is amply hidden by her name alone. Dylan is certainly winking at the listener hear. An everyday Joe is certainly not capable of expressing that riddle. However, it was Dylan himself who first was able to express that kind of cleverness consistently in song lyrics. It's almost as if he is going back in time and planting thoughts in his character's heads, yet he leaves a faint trace... back to himself in the future. The characters and songs are so complete you almost have to think about them in an abstract dimension.

Plenty of places to hide things here if you wanna hide íem bad enough

Iím staying with Aunt Sally, but you know, sheís not really my aunt

Some of these memories you can learn to live with and some of them you caní

However, it's not all blues. "Moonlight" is so rich it is startling. Dylan is ostensibly talking about a rendezvous with a woman, but the subject of his affection is mother nature itself. He is strolling through the countryside describing the litany of her wonders. It's enough to get Ralph Waldo Emerson aroused:

The dusky light, the day is losing, Orchids, Poppies, Black-eyed Susan"Love and Theft" isnít Dylanís greatest album. His material from the 60ís almost makes that impossible. However, it is remarkably powerful. The characters are charming and different. Dylan is full of detail but never bores you. He keeps you on your toes throughout. The album is balanced. A song with a driving beat is sometimes followed by a gentle shuffle. There are love ballads and hard blues. More remarkable than the material though is the road Dylan took to get back to making great records.

The earth and sky that melts with flesh and bone

Wonít you meet me out in the moonlight alone?

"Wherever I am, Iím a 60ís troubadour, a folk-rock relic, a wordsmith from bygone days, a fictitious head of state from a place nobody knows. Iím in the bottomless pit of cultural oblivion. You name it. I canít shake it."

"The kind of crowd that would have to find me would be the kind of crowd who didnít know what yesterday was."

-Bob Dylan, Chronicles

I see the fabulous last song on "Love and Theft" as a kind of coda on the complicated relationship Bob Dylan has had with his fans. I think if there if there has ever been a moment that the real Bob Dylan was speaking honestly and candidly with his fans, it is on "Sugar Baby." A career of smoke and mirrors is stripped away and I think Dylan truly reveals himself in it. Why did it take so long? I think it was because Dylan had to do some weeding. His true words may only resonate with those who had never been exposed to the myths about him. To resonate with a new audience, Bob had to be willing to work. He put in 20 years so he could be honest. What about those who who stayed with him the whole time? I am reminded of a line from "Love and Theft". On the great song "Mississippi," Dylan sings heís got "nothing but affection for those who've sailed with me."

The twisting and elusive dance Dylan and his original fans took part in took its toll on both of them. Dylan became repulsed by those thinking he was some kind of savior or shaman. He began retreating from all he had helped create in 1967. At first he seemed to relish in the rock and roll/ beat poet persona he adopted around 1964. Who can forget Dylan, at turns lecturing and berating a Time Magazine reporter in the film "Don't Look Back"? This is the Dylan with the suit and omnipresent sunglasses. His press conferences of the time are legendary and absurd. He was thrown softballs by reporters used to asking pop singers questions like: "What is your favorite color?" He usually lobbed back hand grenades. When asked what he had wanted to be when he grew up, Dylan once responded: "I always wanted to be a movie usher. So far, I have failed."

He soon grew tired of the games he initiated and moved on. Later in the sixties, he began to see himself as simply a songwriter and something of a country gentleman. But the youth continued to treat him as some kind of god. He was a remarkably young when adulation came his way. Talented: yes. But people his age were coming to him and asking him about the meaning of life. What is a 25 year old supposed to say about that?

Dylanís work in the mid-sixties (especially Highway 61 Revisited) made it clear that he was both exasperated by the idol worship of his fans and the idealism of his generation. What could be more of a rejection of idealism and the hypocrisy of those wanting it than "Like A Rolling Stone?" Dylanís message in it is clear: it is easy to be an idealist when you are born with a silver spoon in your mouth. But when you actually experience the real world, you will be compromised. Dylan had learned that utopia can only exist in a vacuum. The pretty little girl in that song quickly learns that she must put out in order to live. Dylan had already learned that hard lesson and wants to be there at that moment when reality shatters delusion. He sadistically wants to ask "how does it feel?" at that moment. What could be more of an expression of the exasperation of dealing with fame than "Positively Fourth Street?" Dylan ends it with:

I wish that for just one timeIt is surreal and sad for someone my age to contemplate that fans had so much invested in Dylan. Someone they had never even met. But it is true. It is also funny to picture the unwashed hippie masses gathering on his lawn waiting for him to answer their questions and even digging in his trash. But that happened too. It became convenient for him to constantly switch personas. "You want to know the meaning of these lyrics? That Dylan doesnít work here anymore. He's long gone."

You could stand inside my shoes

And just for that one moment

I could be you

Dylan had also led many brilliant musicians (also all fans) down a road that he wanted to abandon as well. Looking back, the road was essentially a dead end. On some levels, Sgt Pepperís was a logical evolution from Dylan's surreal lyrical work of the mid-sixties. It was almost with a mild sense of embarrassment that Dylan described the album to an interviewer as "very indulgent." One can almost believe that Dylan wanted to hide, not only from the mobs of fans, but from a musical train he had helped create that was now veering off the tracks. Psychedelic music was usually nothing more than artists of a lesser ilk trying to recreate "Mr. Tambourine Man" at a higher volume. Would the world have been subjected to a band called The Strawberry Alarm Clock without Dylan's "Visions of Johanna?" Probably not. Psychedelic music basically became a fad that seems unbelievably dated now. Yet, because of Dylan, even some of the most fabled bands strayed and fell into its trap (ask The Rolling Stones). Dylan seemed to have accurately summed up the future this particular type of music and the expectation of his fans as early as 1965. On Highway 61 Revisited song "Desolation Row," Dylan sang:

The Titanic sails at dawnMuch like his conversion from folk to rock, Dylan saw the writing on the wall well before anyone else did. Shortly after "The Summer of Love" Dylan was executing his most brilliant twist. In the fall of 1967 he began work on John Wesley Harding. It was not recorded in Woodstock, or San Francisco, or New York City, but Nashville. Dylan dropped The Band and used session musicians who were paid hourly. This was hardly considered the epitome of a hip scene.

And everybodyís shouting, "Which side are you on?"

It is a remarkably sparse album. There is not an electric guitar to be heard on it. In it, Dylan was not looking forward to revolutionary future, but to a strange and fabled past. The album consisted of Old Testament imagery and judgment. Dylan may have still been speaking riddles, but the language and music was far less provocative and confrontational.

This turn was followed by a country album (Nashville Skyline) and then one of mostly covers (Self Portrait). It became clear that Dylan was probably (!) not playing some elaborate joke. Dylanís original fans had already written him off. Now the fans Dylan had gained as a rock artist became offended. Even before he converted to Christianity, rock fans saw his new work as some kind of betrayal. If Dylan didnít deliver what was expected, it was taken intensely personally. The Rolling Stone review of Self Portrait began famously with "What is this shit?" Some wondered, how could an authentic artist be so many different people? Who was Dylan trying to be now? A folkie? A hippie? A bumpkin? A Christian? A Jew? A square? They were confused. They somehow figured his talent belonged to them. How could he deprive them of his leadership when their generation needed it so badly?

Looking back, it is not that surprising that Dylan almost washed into complete irrelevance in the 1980ís. He was disillusioned. His fans were disillusioned. Their relationship seemed irrevocably broken. It is almost as if even he did not know who he was supposed to be anymore. The twist and turns in image and music that were once so fascinating and brilliant had grown tiresome. Dylan could not find his way back.

Dylan seemed confused and stymied by modern recording techniques. Part of his genius had always been the spontaneity of his performances. "Like a Rolling Stone" was recorded live in the studio. It took 15 takes, but the payoff was unbelievably immense. In the early days, almost every brilliant performance was a single moment in time. The recordings were hardly touched after the musicians got up from their stools. After 1975ís Blood on the Tracks, it seemed he could not muster that energy or find that spark anymore.

The Ď80's saw Dylan a washed in overdubs. One cringes to think of Dylan in a studio with the producer du jour punching in lyrics, a line at a time, over pre-recorded tracks. His voice was straining to come out. But Dylan somehow kept you hanging on. For every ten head scratchers and embarrassments there was a "Ring Them Bells" or an "Every Grain of Sand." Maybe the brilliance was still there but was being corrupted by others. Maybe he was trying to figure out what other people wanted, and thus, trying too hard. You didn't know.

It is clear that for a time that Dylan, the most versatile of artists, was unsure of his own talent. He stumbled along making mediocre records. Proof of his timidity is the fact that at the time, he still recorded brilliant songs and left and them off records (ED NOTE: but didnít he always?), with "Blind Willie McTell" being one. These songs were usually replaced with filler. Dylan faced a fork in the road. He could sit back and relax until the cows came home, or he could start all over again. He chose the later. And as is written in Chronicles chose to cultivate a new fan base not based on mythology but on music alone. This long road (literally) started and continues with the "Never Ending Tour" and, in many ways, ended in "Love and Theft".

Dylan found himself and a new audience over the course of 20 years while riding on a tour bus. He has averaged more than 100 shows a year for the last 23 years. He has returned every year to long neglected and obscure places in middle America. Dylan does not need the money. He is simply searching for a connection with new, younger fans. He wants a connection that was not strained by years of misunderstandings. He started fresh and was embraced by these fans. It took awhile but he did it.

The fact that Dylan was revitalized quickly began to show in the studio. 1998ís Time Out of Mind was quickly hailed as a return to form. Much was made of producer Daniel Lanoisís ability to prod Dylan and also get a unique sound. The songs were strong, no doubt. However, Dylan still seemed distant and buried. "Dirt Road Blues" seems to have all the makings of a powerhouse, except the sound itself. Dylan voice sounds distorted and very far away. You have to strain to hear the snare drum. That would be rectified on "Love and Theft" on which Dylanís voice sounds raw and parched and the drums rumble and the guitars ring. Dylanís voice on the album may be the only positive testimonial to the long term effects of cigarette smoking. It is worth noting that Dylan produced the album himself (under a pseudonym).

Dylan had regained his confidence. He was very grateful for his new fans. On Time out of Mind, he mentions how he would trade places with any young person if he could. He had been given a new lease on life by people half his age. He must have wondered how they could relate to him. Maybe he wondered what he could do for themselves? It is fitting that "Sugar Baby" starts with a sense of perspective. Itís almost as if Dylan is looking down at those beginning to climb a mountain. Or he is at the end of that fabled lost highway, looking back. He is speaking to those who have not run the gamut of lifeís travails, but soon will. He starts:

I got my back to the sun ícause the light is too intenseDylan proceeds to dish out nuggets of wisdom about love, sex, friendship and life in general in an intimate 6 minutes. It is as if in this moment you are sitting at Dylanís feet and he is telling you how life will be. He is insistent that it will not always be pleasant or what you want. Life can be ugly and downright cruel. He actually describes life as one big "dirty trick." Yet his tone in the verses is not bitter or even forceful. It seems to be in the manner in which a father would address his children: plain and loving.

I can see what everybody in the world is up against

You canít turn back--you canít come back, sometimes we push too far

One day youíll open up your eyes and youíll see where we are

However, it is clear that the advice he is giving is not for his "Sugar Baby." He was abandoned by her long ago and for her alone he reserves a special type of scorn. In the refrain, he becomes dismissive and harsh. He sings:

Sugar Baby get on down the roadIt is obvious Dylan is speaking to those who relished putting him on a pedestal, then breaking him down. He is speaking to those who thought he was washed up and long dead. He has been vindicated and does not need his "Sugar Baby" anymore. He does not lose sleep wondering where she is or what she thinks. He is an old man but he is far from broken. He is hopeful about the future even if there is not much of one left for him. In the last verse he sings:

You ainít got no brains, no how

You went years without me

Might as well keep going now

Just as sure as weíre living, just as sure as youíre bornItís reassuring that Dylan ends the album with an affirmation of divine providence. But why should a person my age even care what Dylan has to say? For me, itís certainly hard to relate to the time that Dylan was viewed as a walking divinity. However, that may be the reason why it was recorded. The hipsters of that time seemed so sure of themselves and the future and ended up looking so naive. I believe that war, greed and poverty will continue in this world no matter how much you march, chant, or sing. They are symptoms of the disease of humanity. Dylan himself once said, "a song canít change the world."

Look up, look up--seek your Maker--ífore Gabriel blows his horn

Maybe Iím jaded about the idea of these "flower children." But Dylan became jaded too and he actually knew them in their primes. I can smell their fakeness 40 years on and Dylan shook their hands. That should tell you something. And that is what makes an icon of another era so appealing to me. The fact that he can be an icon of an era which he came to despise is fascinating and cruel and cool. What is more rock ní roll than being misunderstood, right? But, in other peopleís minds, he is something he doesnít want to be remembered as. I can relate to his repudiation of an idea or idealism itself. But that in itself is not enough. There is the music, but that is not the only reason why I want to listen to what he has to say about life.

I often ask myself if I could interview any living musician, who would it be? I would take into account the things theyíve witnessed, the people theyíve met, the things theyíve created, and they places theyíve traveled. I always come back to Bob Dylan. This is a man who looked Buddy Holly in the eye. This is a man who was one of the last friends of a dying Woody Guthrie. This is a man who kept the Beatles nervously pacing in waiting rooms. This is a man who was in a band with Roy Orbison. It is important that those are facts, not myths. What makes him more intriguing is his fallibility and work ethic. Genius seemed to flow so easily from him at first. But then it got hard. He eventually alienated everyone and gave up everything that seemed to matter to everyone but him. He could have easily worn the crown he was given. But he chose not to, because he did not believe in what the mantle represented anymore. He was loved then despised and started all over again. He has lived the equivalent of 10 lifetimes. I would choose to interview him.

So, if "Sugar Baby" is Dylan speaking from the heart, it is important to me. But, what if Iím wrong? What if "Sugar Baby" is just a good song and it doesnít mean what I think it does? What if Dylan quickly scribbled its lyrics on a napkin while riding to the studio? Iím fine with that. I have nothing riding on Dylan and he owes me nothing. He has given me countless hours of entertainment and I have put a few dollars in his pocket. Weíre square. He is not a God. I cannot be struck down by him. Dylan was "washed up" before I was even born. I am thankful for "Love and Theft", but I know it is only an album and he is only a man.

Dylan's Christmas album

Dylan biographer Dennis McDouglas interview

Dylan's Blood on the Tracks