BOB DYLAN

Dennis McDougal covers his 60's/70's peaks

Interview by John Wisniewski

(June 2015)

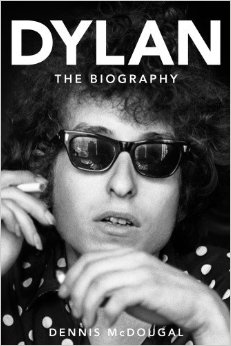

Into the crowded field which covers a certain beloved classic rock subject comes newspaper columnist and journalist Dennis McDougal with his new book Bob Dylan: The Biography. McDougal's writing background is interesting- in his previous books, he's covered a Hollywood mogul, a newspaper family dynasty, a number of murder cases and legendary actor Jack Nicholson.

In this interview, McDougal speaks about his Dylan book, providing us with the critical reactions to many of Dylan's greatest albums and other subjects such as Dylan's motorcycle accident, the (in)famous 'Royal Albert Hall' concert with The Band where Dylan was jeered by some disappointed fans and Dylan as a counterculture spokesman. As such, McDougal answers many questions about Dylan's life and times and provides insight about it.

PSF: Why did you choose to write your book about Bob Dylan?

Dennis McDougal: Two men personified (for me) what it meant to be an American male in the last half of the 20th century: Jack Nicholson and Bob Dylan. Nicholson did it on screen from Easy Rider to About Schmidt, showing the full range of emotion, physicality, psychological brood and existential lust that both plagued and blessed bewildered young men like myself. While I was trying to figure out who I was and how I fit in during an era of rapid, chaotic change, each Nicholson movie gave me a role model to follow. Music, the other great guide post on my road to maturity, was dominated during that same period by Dylan. His lyrics spoke to my heart in much the same way Nicholson's movies spoke to my mind. When my publisher, John Wiley & Sons, asked me what I wanted to do next after the success of my first two biographies (Universal Pictures' chief Lew Wasserman [The Last Mogul] and Los Angeles Times publisher Otis Chandler [Privileged Son]), I didn't hesitate. Nicholson and Dylan -- my last two heroes during a half century of Vietnam-influenced cynicism and political disillusion. Jack and Bob were, and still are, icons worth knowing better and better. Understand each of them, and you inevitably come to understand yourself.

PSF: Why was Dylan a rebel?

DMD: Dylan was less a rebel than he was a visionary. He appeared to be rebellious in the early 1960’s because his elders — the so-called Greatest Generation of World War II — still believed in Jim Crow, the threat of Communism and American exceptionalism. The Baby Boom believed in none of it. Like Dylan, the younger generation championed Civil Rights while opposing the Vietnam War. The counterculture mantra - “Question Authority” - also became Bob Dylan’s slogan.

And yet Dylan was also deeply traditional. Before protest and demonstrations overtook the late ‘60’s, Dylan married, fathered four children and withdrew to Woodstock where he steeped himself in mysticism, macrobiotics and traditional Judaism. While pop music metamorphisized from sappy teeny-bopper tunes to anti-war anthems, Dylan returned to American root music in the basement of the Band’s Big Pink dorm in the Catskill Mountains. It was the second time that he stubbornly turned his back on the status quo and followed his own path. Famously, the first time was in the summer of 1965 when he went electric. He did it again in 1979 when he publicly declared he’d been born again as a Christian. Dylan has always gone his own way but refuses to align himself with any movement or cause.

Is he a rebel? Sometimes it seems so, but upon closer examination it is actually an artist keeping his own counsel. He has never called himself a spokesman or a leader and, in fact, has always gone out of his way to say otherwise.

PSF: What may have happened to Dylan in 1967? Was there really a motorcycle crash?

DMD: Dylan famously lost control of his motorcycle during a ride through the Woodstock countryside in July of 1966. Precisely what happened and how has never been clear, but the result was that the singer-songwriter, who had just completed a triumphant and highly-publicized tour in England, became a recluse. He allegedly broke bones in his neck and checked into rehab with a local doctor who oversaw his recovery. To his fans, who had grown into the millions, the difference between the psychedelic rock hero of Blonde on Blonde and the subdued family man who recorded John Wesley Harding was nothing short of astonishing. The motorcycle accident ended the 25-year-old pop icon's mystic hipster phase and opened the door to his return to American roots music. In relative solitude, a long way from the spotlight, he began dabbling in film making, experimenting with the Band in the basement of Big Pink, and raising a family out of the public eye. Not until his re-emergence at the Isle of Wight music festival in England a few weeks after the Woodstock Festival in the summer of 1969 did he show himself to his fans. The cat-and-mouse game served him well in the long run though, making the curiosity surrounding his vanishing act stronger than ever. By the 1970’s, Bob Dylan was a bona fide music hero around the world.

PSF: Did Dylan really introduce the The Beatles to marijuana which may have changed the sound of their music?

DMD: According to rock lore, Dylan met the Beatles in a New York hotel room August 28, 1964. Journalist Al Aronowitz recorded the moment in one of his notebooks, citing this first encounter as the moment when Bob introduced John, Paul, George and Ringo to cannabis. There’s no way of verifying whether or not the Beatles had toked before, but there is no argument that this was a summit that would transform pop music forever. Dylan’s next album Bringing It All Back Home was the first of his ground-breaking trilogy of psychedelic rock classics — the other two being Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. The Beatles followed up the meeting with Bob by releasing the folk tinged Rubber Soul and Revolver. The joint they passed around that day didn’t change music, but the mutual respect and influence that they had upon each other did.

PSF: The audience reaction to Dylan playing electric at Albert Hall is legendary. Why did the some feel betrayed by Dylan's new approach to his sound?

DMD: The 1960’s were pretty evenly divided musically. Prior to 1965, pop was either treacle and bubble gum or Presley rock and roll. The only other tradition then emanating out of the post-Beat coffee house scene was folk. Dylan followed folk music out of Minnesota and into Greenwich Village in 1961 where he took folk, bluegrass, ballads and blues as far as he could before he began experimenting with the electric rock he grew up with in Hibbing. By his third album, The Times They Are A-Changin', his turn away from acoustic was pretty much assured. The album's title is ironic in that his music was also a'changin'. There were hints of electrification on Another Side of Bob Dylan, but one whole side of Bringing It All Back Home was bona fide rock, including the original rap song, “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” Dylan was a trailblazer, a maverick and an artist true only to his muse. Throughout his career, fans have felt betrayed, over and over and over again. The first outrage, at Newport and Albert Hall, was a reaction to his trading in a Gibson flat top for a Fender, but it would not be the last. Down to the present day, he still gets raked over the coals for going his own way. Critics carp over his voice, his improvisation, his choice of material, but Bob doesn't give a damn. Bob keeps on keepin' on, his latest effort showing that at 74, he hasn't let up trying new approaches. After suffering slings and arrows over his Christmas album of a few years back, he is now channeling Sinatra and doing a commendable job. Like all writers and artists, Dylan experiments. Sometimes he hits, sometimes he misses, but unlike too many of his peers, he never falls into a rut.

PSF: What was the reaction to the Dylan album John Wesley Harding?

DMD: Most critics haled John Wesley Harding as another Dylan "concept" album in the vein of Blonde on Blonde and Highway 61, though its heavy Biblical imagery and eventual influence eluded them. It was widely viewed as Dylan's first of many "return to roots," reflecting as it did apocalyptic lyrics coupled with the folksy ballads of Bob's earliest efforts. The album's chief significance didn't become apparent until several years later, after the Band's Big Pink foreshadowed the Basement Tapes and the quiet revolution that took place during 1967-68 in the solitude of Woodstock. The influence that pooling of talent had on pop for generations to come, emphasizing a genre loosely known today as "Americana," remains immeasurable, but we feel it even now in the Zack Brown Band, Wilco. Mumford & Sons, Jack White and a hundred other musical acts. John Wesley Harding was the nexis and American rock and roll has never been the same since.

PSF: Nashville Skyline was recorded with Johnny Cash. How did that happen and what was the aftermath?

DMD: Dylan and Cash met at the Newport Folk Festival six years prior to the recording of Nashville Skyline, which is still the only Dylan album featured in and sold at the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, where Cash is lionized as a hero and Dylan is barely mentioned. They were instant friends and remained so for life, recognizing in each other a passion for roots music and genuine poetry. While white bread America -- raised on Roy Acuff, Porter Waggoner and Patsy Cline -- preferred Cash, Dylan attracted a more ecumenical audience steeped in the blues as well as country-western. But despite the disparity of their fans, Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash remained soul brothers throughout their lives.

PSF: What was the intention of Dylan and the Band recording The Basement Tapes?

DMD: The Basement Tapes were released as a corporate answer to bootleg albums such as The Great White Wonder, which began selling surreptitiously as early as 1969. Band member Garth Hudson used state of the art recording equipment to tape the sessions that Dylan participated in at Big Pink, the hippodrome in the woods east of Woodstock where the Band recorded their first album. Hudson's tapes were made into acetates and sent out to other recording artists who were clamoring for more Dylan material to record during the late ‘60’s and early ‘70’s. These acetates became the basis for the original bootlegs which, in turn, became the enhanced recordings that Columbia released years later as The Basement Tapes. While the album was meant to discourage bootleggers from stealing Bob and Band music and selling it illegally, it turned out to be one of Dylan's bestselling albums and later formed the basis of ‘The Bootleg Series.’

PSF: Was New Morning the beginning of Dylan 's religious awakening?

DMD: New Morning was greeted as reassurance that Dylan had not totally lost his mind with his Self Portrait album released just six months earlier. Rolling Stone's Greil Marcus famously opened his review of Portrait with the line, "What is this shit?" A hodge-podge of chestnuts, retreads and non original tunes that seemed to be thrown together, Portrait was so poorly received that many critics thought Dylan had released it simply to piss off overzealous fans intent on drawing him into the growing debate about Vietnam. New Morning, while not one of his better albums, was nonetheless a return to form with folksy original lyrics and the clear crooning that had made Nashville Skyline one of his bestselling albums. The poetry was neither as allusive or Biblical as John Wesley Harding, but still clearly in the vein of his reclusive Woodstock period, when home and family were far more important to him than tapping into the soul or seeking out the meaning of life. Clearly, any religious awakening was still ten years off, when a vision of Christ in a Tucson motel room led him to begin preaching fundamentalism from the stage.

PSF: Dylan played live at Concert for Bangladesh and again with The Band as recorded for Before the Flood. Why did Dylan decide to appear live again?

DMD: Dylan actually began re-emerging at the Isle of Wight concert weeks after Woodstock. Part of the reason was money. Then, as now, a musician takes home a lot more ready cash from a concert than he does from record sales and playing before stadium audiences is a huge payday. Dylan was never in danger of poverty, but he had a family, business and investments to sustain. Bangladesh, however, was an act of pure generosity prompted by his close and lifelong friendship with George Harrison. Dylan's return to the stage in the early '70’s was deliberate and gradual. More a business decision than a return to performance art, the David Geffen-orchestrated release of Planet Waves and accompanying national promotional concert tour that resulted in Before the Flood and later Scorsese's The Last Waltz were all designed to cash in on the Dylan/Band popularity. Little of lasting popularity emerged from Bob's lyric imagination during this time except for his paean to son Jakob -- the classic "Forever Young."

PSF: How did Dylan become interested in the story of boxer Reuben "Hurricane" Carter?

DMD: Since his early protest song "Who Killed Davy Moore?” Dylan evinced a passion for boxing. Growing up in Hibbing, he heard his father and uncles hover over the TV whenever there was a prize fight and later adopted boxing as his own favored sport, both as spectator and participant. When he bought a Santa Monica coffee shop in the early 1990’s, he installed a gym and boxing ring behind the bar where he and his friends could spar and punch the heavy bag between pots of coffee and games of chess. Dylan never missed a match between name boxers when he wasn't on tour. Thus, his interest peaked when he read about Rubin Carter's murder conviction and subsequent legal battles to overturn the state of New Jersey's guilty verdict. He read Carter's own account of the events leading up to the bar killings and his arrest, all based on hearsay evidence and what Carter purported to be false and/or coerced testimony. Dylan adopted Carter's cause as his own and made the song "Hurricane" a centerpiece of his Rolling Thunder tour in 1975. The song arguably won Carter a retrial, but not acquittal. It was only several years later and a stalemate between defense and prosecution before the New Jersey appellate court that the conviction was finally thrown out and Carter was freed. He moved to Toronto where he became a counselor to others wrongly convicted of crimes until his death in 2014.

PSF: Not to forget Blood on the Tracks. Was this album a triumph for Dylan?

DMD: IMHO, Blood on the Tracks was -- and is -- Dylan's masterpiece. He has pronounced it an outflowing of pain that is hard for him to bear, let alone hear. The album is testimony to mid life crisis, coming as it did on the penultimate breakup and reconciliation of his marriage ot Sara Lowndes. The album, highlighted by the rhapsodic yet enigmatic “Tangled Up in Blue,” transcends all that Dylan did before or after -- the jewel in the Zimmerman crown. His fans agreed. BOTT was his bestseller since he peaked in the 1960s. A triumph indeed.

Also see these other articles:

Dylan's 'Love and Theft'

Dylan's Christmas album

Dylan's Blood on the Tracks