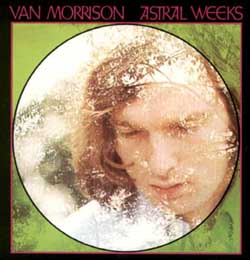

Astral Weeks and the Troubles

by Kevin Parker (April 2003)

Recently, the arts organization Factotum published a book entitled Belfast Songs, a collection of musings on the city and those who choose to sing about it. Writing for the Manchester Guardian, Matthew Collin commented on Van Morrison's Astral Weeks: "The record was released in 1968 as political violence escalated, but Morrison reminisced about a more innocent time, recounting the sights and sounds of a bygone life while escaping into his imagination, an oasis of romantic reverie." An object of personal obsession, I have read many things about Astral Weeks, but none connected the album to Northern Ireland's "Troubles," and despite my knowledge of the album and Van's origins, I never made the connection myself.I have listened to Astral Weeks many, many times (probably as many as Nick Hornby has listened to "Thunder Road") and I find some new thrill in each listen. I spent several hundred listens trying to make emotional, if logical, sense of the lyrics. Gradually, this revealed a strange narrative (which, to me, compliments Van's own assertion that Astral Weeks is some sort of rock opera). Once I found a narrative, though, I had no more realizations about the album. They were small understandings: how the strings' entrance on "Astral Weeks" suddenly creates drama; Richard Davis' bass, by jumping up an octave in the trombone solo of "The Way Young Lovers Do" causes the song to tumble into the chorus; how Connie Kaye's off-kilter cymbal work at the end of "Madame George" adds poignancy. This last listen, though, felt something like an epiphany. "The record was released in 1968 as political violence escalated."

Before, I believed Astral Weeks was the painful story of one man who, by way of his obsession with a fourteen-year-old schoolgirl, becomes the tragicomic figure of Madame George. The first half of the album, titled "In the Beginning," chronicles this man's (or boy's) estrangement ("I ain't nothing but a stranger in this world"), loss of innocence ("Beside You"), and euphoria of new love ("The Sweet Thing"). Then, something strange happens. The narrator falls in love with a fourteen-year-old girl. Acknowledging my debt to Lester Bangs, I claim only that Van has imagined a character but made no moral judgments about him; Van has dared to ask what if this man genuinely loves her as a person – as a human being – and not as the sick obsession of a pedophile.

(Also, as listeners, we assume that the narrator is far older than she is, but there is no evidence of that. We know only that he drives a car and walks by the railroad tracks with his cherry, cherry wine. He could be in his early 20's, late 30's, or mid 60's. What if the narrator is only 18?)

Wracked by the pain of this love he cannot express, the narrator becomes "Madame George," and Van shifts the perspective from first person to second person – just as he did in "Beside You." Just as the child is leaving Madame George for the last (first and last?) time, there is human contact. They touch hands, and, in that touch, the child experiences genuine compassion for another human being. It is compassion nearly divine in its depth (hence the rapturous repetition of "the love that loves"). The final songs, "Ballerina" and "Slim Slow Slider," are from the perspective of Madame George, still pining over this girl. Years lapse between "Cyprus Avenue" and "Madame George," and the girl is nearly an adult by now. Nonetheless, it became impossible for Madame George to meet her long ago. He has to resign himself to these last, fleeting glances of her. As the final song begins to fade, he offers up one last cry of frustration, "Every time I see you, I don't know what to do."

Beyond the heartbreak of the loose narrative, though, I always heard some other sense of tragedy that I could never name. Of course, this reaction is only natural. Everything about Astral Weeks seeks to subvert a sense of narrative: "Madame George" is the closest thing to a story-song the album contains, and even that is gloriously nonlinear. Van Morrison was seeking to evoke sentiments and images and tell a story via their emotional charge rather than following any notions of plot or structure. In revealing a story (as opposed to telling one) in such an oblique manner, the listener is destined to experience emotions without any direct cause. For me, it felt as though the narrator was not telling the whole story – as though Madame George, Cyprus Avenue, and the ballerina were only part of a frame whose interior Van never reveals. In an interview, the album's bassist, Richard Davis, commented on how the dusk recording sessions affected the music. In a 2001 article for Mojo, Barney Hoskyns explains how awkward the sessions were, "Isolated in the studio's vocal booth, Van barely exchanged a word with the other musicians." It is not difficult to hear this on the album, but I would hesitate to label it as an estrangement between Van and the musicians, because there is too much of a connection in the performances. The separation is more ethereal; the strings, bass, drums, guitar (and harpsichord and flute) are like the angels in Wim Wenders' Wings of Desire – just over your shoulder, knowing everything, but unable to even say hello. The circumstances surrounding the album may explain the musician's performances, but they do not explain Van's singing or the songs themselves. The key, I found, was in the first half of Collin's statement. "The record was released in 1968 as political violence escalated."

When we, particularly Americans, speak of Northern Ireland, we ignore the radical changes that the Troubles wracked upon it. As Gerald Dawe states in The Rest is History:

Memory plays tricks with historical reality but it seems to me looking back over 25 years towards the twelve months between the end of 1969 and 1970, everyone was playing Astral Weeks throughout the Belfast which I knew. That year was a watershed for every generation in Belfast, but particularly so for those of us who were leaving our teenage years behind and becoming young men and women. Friends would soon go their own way, across the water to England, taking up jobs, going to college, disappearing. The months leading out of the 1960s into the 1970s correspond, loosely and in an inchoate and inarticulate way, with a social and cultural breakup of life as we had known it. [emphasis mine]There is no mention of political violence on Astral Weeks, and Van actually wrote all but two of the songs during his residence in Massachusetts. However, it is clear that Van was writing and singing about the Belfast of his childhood. According to Hoskyns, Van sank into an alcohol-aided depression while living in New England. A recording artist with a top ten hit and a professional musician since the age of 15, Van was a has-been at 21 and performing at high school dances. Inevitably, his thoughts must have drifted back to a happier time in his life, and must have reflected on his last times in Belfast and how that city was changing.

Although Astral Weeks never leaves Belfast (it barely leaves the city section of Orangefield), we do not learn Van's own feelings for Belfast until much later. "And It Stoned Me" (from Moondance, 1970) reveals pastoral recollections of childhood, but it works as a metaphor for memory rather than a specific comment on Belfast. In "St. Dominic's Preview" (from the album of the same name, 1972), Van hints at the escalating Troubles ("badges, flags, and emblems"), but only as he searches for something more lasting. On "Coney Island" (from Avalon Sunset, 1989) and "In the Days Before Rock and Roll" (from Enlightenment, 1990) Van pines for the Belfast of his childhood. Yet, he laces his yearning with affection. It is not until 1991's Hymns to the Silence that we understand just how profoundly upsetting these tectonic shifts in Belfast society have effected him. In "See Me Through Part II," Van echoes "Coney Island" and "In The Days Before Rock and Roll," clearly sensing value in what has been lost: "Take me back, take me way back/To Hyndford Street and Hank Williams."

What follows this is Van's profound melding of gospel and blues, "Tack Me Back." Its narrator, expressing a frustration with and helpless in the world, wishes for his childhood world to return. "Take me back," he repeats, as though the repetition can conjure the past for him. It is tempting to dismiss this song as mere nostalgia, but when you consider Dawe's statement ("a social and cultural breakup of life as we had known it"), you can sense something most of us have never experienced. Van's home, his childhood, and the source of his inspiration ("There's a place in your heart you know from the start/ Can't be complete outside of the street") has utterly vanished – the breakup of life as he had known it. Imagine the pain it must cause someone to walk through the streets of their hometown, to see that it has utterly disappeared. In 1991, Steve Turner revisited Van Morrison's Belfast and wrote in the Independent, "Few of the places he knew in those days remain intact and the character of the city has been altered the military patrols, spot checks and security gates."

Earlier, I stated that Astral Weeks seemed to have a frame story with no interior, but it is the converse that is true. We have the particular tale, the interior, articulated, but not its frame story. With extraordinary prescience, Van reconstructed the Belfast of his childhood with Astral Weeks even as it was being destroyed around him (or, to be literal, across the sea from him, as he supposedly wrote the album in Boston before recording it in New York). Van understood, better than other artists I have encountered, the real cost of The Troubles. In a place where identity politics have been exploited to ruthless ends, the genuine contact and company Astral Weeks' characters so desperately seek becomes impossible. Whether consciously or not, Van recognized this and he was able to articulate it in these songs. That is why everyone that Dawes knew was listening to Astral Weeks in the late ‘60's and early ‘70's. The album is as much a eulogy for a way of life as it is tales about love, obsession and mysticism. Van was able to preserve an element of that Belfast before its last vestiges crumbled away.

It is an odd album, really; an anomaly for its time, style (a strange fusion of folk, jazz, and blues) and even its author. Van would never again stray so far from his R&B roots. At the time, no one could have guessed that a twenty-two year old Belfast native, whose previous output included collaborations with pop architect Bert Berns and the R&B combo Them, could produce it. Listening even to songs recorded just a year before Astral Weeks, there is no clear indication that Van had anything like this in him. Perhaps possible explanation is the imminent cataclysm in Belfast may have awakened something in the Belfast Cowboy. That would make for a strangely appropriate benediction. Van's childhood Belfast, which nurtured his imagination and for which he has such affection, gave birth to a singular piece of art (and artist) in its death. Thirty-five years later, Van is still grappling with the epiphanies he reached – caught, one more time, on Cyprus Avenue.