The Asian Improv:

Adventures in Cross Cultural Synthesis

Jon Jang and his Pan Asian Arkestra, courtesy of In Motion Magazine

by Dave Kaufman (August 1998)

For as long as I can remember, critics and commentators have bemoaned the stagnant state of affairs in jazz music, citing a lack of innovation and creative spark among contemporary practitioners. Certainly, there are conservative and regressive elements in jazz, as in any other musical genre. However, there have always been exciting currents and inventive musicians that continue to revitalize and redefine the boundaries of this tradition. This African-American art form has been richly informed by music of the world for the better part of this century. This has infused fresh ideas, new rhythms, and harmonic possibilities into the jazz tradition. Latin sounds and rhythms have long since become an integral part of the jazz idiom. Similarly, the music of Africa has served as a wellspring for many musicians. Some practitioners have merely exploited these foreign sounds to add exotic flavoring and spice into their musical mix. A sprinkling of conga drums here and there or a splash of kalimba (an African thumb piano) add coloration, and may increase an artist's commercial possibilities. However, numerous artists such as Abdullah Ibrahim and Randy Weston have created an organic synthesis that is a wholly distinct musical form without any visible boundaries. This music, based on an in depth understanding of their musical roots, lays bare the points of common origin.Eastern music has had a considerable impact on the evolution of jazz since the 1950's. However, jazz musicians have only begun to explore the immensely rich variety of musical styles originating from the Asian continent. Some of the freshest, most innovative, and compelling sounds have emerged from a movement known as the Asian Improv. This movement consists of a growing number of (mostly) Asian American artists such as Jon Jang, Francis Wong, Glenn Horiuchi, Mark Izu, Miya Masaoka, Fred Ho, Jeff Song, Jason Kao Hwang, and Vijay Iyer. African American artists such as Anthony Brown and James Newton have also played an instrumental role in the evolution of this art form. Asian Improv music is not reflected in any one style, but in a strikingly diverse body of work that draws on a range of traditional classical and folk musics from countries such as China, Japan, India, Korea, and the Philippines. These artists all share a profound appreciation of the jazz tradition from Ellington to Mingus to the contemporary vanguard. This music is not borne out of hybridity, facile East-meets-West fusion or any conscious mixing of styles but of a more organic deeply rooted understanding of the jazz idiom as well as the music of their ancestry.

The Asian Improv movement is also a product of a growing political consciousness and activism in the Asian artistic (and broader) community. Many of these artists are first generation American-born and have experienced a sense of marginalization and exclusion from the American mainstream and music industry. Although they may not have experienced the overt racism and institutional discrimination to the extent that their parents have, the culture of division and intolerance of difference has informed their lives and their art. This sentiment is eloquently expressed in the following quote by pianist Vijay Iyer, from the liner notes to his excellent CD Architextures:

"The music in this collection has emerged from my ongoing efforts to document my life experiences. It depicts what I have learned as a member of the post-colonial, multicultural South Asian diaspora, as a person of color peering in critically from the margins of American mainstream culture, and as a human with a body, a mind, memories, emotions, and spiritual aspirations. As I am a member of a growing community of first- and second-generation Indians, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Afghans, Nepalis, and Sri Lankans in North America, my music should be received as a real outcome of this diverse community. I function not as its official representative, but merely as a single voice -- one among millions."

The sense of intolerance, isolation, and misunderstanding is a vital link that connects Asian Improv artists to jazz and the African American experience. This point was effectively conveyed by kotoist Miya Masaoka in an interview with Dan Ouellete (Pulse, 1998). She states "Our music comes from a culture in diaspora. That's why jazz, which developed out of the African diaspora is so attractive to Asian Americans." The Asian Improv movement developed in the 1980s, at a time when there was a growing political activism in the Asian American community, as exemplified by the Redress and Repatriation movement (efforts to seek acknowledgment of harmful wrongdoing and compensation for the government internment of Japanese Americans during World War II). This has coincided with an artistic and cultural renaissance within the Asian American community that has been reflected in major achievements in literature, cinema, and graphic arts.

The center of the Asian Improv universe is the San Francisco Bay Area and Asian Improv Records (AIR). Pianist Jon Jang and Francis Wong founded this label in 1987. Since that time they have developed a catalog of over 30 titles representing some of the greatest works in this movement (www.asianimprov.com). Jang and Wong recount the events leading to the origin of the label, as well as its subsequent history in great detail in a highly informative interview published in In Motion Magazine to commemorate the label's 10th anniversary.

In 1993, Jang and the Pan Asian Arkestra, an 11 piece group featuring both Western and Chinese instrumentation, released the landmark recording Tiananmen!. The album is a tribute to those individuals in the Chinese democracy movement who gave their lives in that tragic event. Tiananmen! is a work of astonishing depth, complexity, and beauty, representing a perfect marriage between modern orchestral jazz and traditional Chinese (classical and folk) music. This work has been properly compared to an Ellingtonian Suite (it has that sense of grandeur) or one of Mingus' compositions for large ensemble. It also reminds me of the magnificent politically informed works by Charlie Haden's Liberation Music Orchestra (Liberation Music Orchestra and Ballad of the Fallen). Tiananmen! is one of the best jazz recordings of the 1990s and is arguably a desert island disk. Jang's follow-up recording, a sextet date that features David Murray on tenor and James Newton on flute, is almost as good. Francis Wong's first recording, the Great Wall of China, is a strikingly beautiful quartet date that blends straight-ahead jazz with traditional Chinese folk music. Wong is a tenor player of considerable abilities and is as equally well-versed in bop as he is in the avant-garde.

New York-based baritone saxophonist Fred Ho and his Monkey Orchestra recorded one of the more ambitious works in the Asian Improv Idiom. The Monkey Part 1 and Part 2 (released as 2 separate disks) is partially based on a 16th century Chinese epic and draws on various literary works. As I understand, it was also presented as a multimedia theatrical work. Like Jang's Arkestra, this 13-piece group features both Chinese and jazz instrumentation. The recordings are a largely successful and often brilliant combination of free jazz, Chinese opera, and renditions of Mandarin poetry. This description doesn't begin to do justice to this complex and majestic orchestral work. Theatre and mixed media performance has played an increasingly important role in the Asian Improv community. I would rank Ho's recordings just a notch below Tiananmen!-very highly recommended.

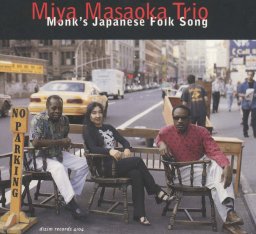

One of my favorite recordings of the last couple of years is a CD by

kotoist Miya Masaoka, called Monk's Japanese Folk Song. This superb

collection consists of compositions penned or inspired by Thelonious Monk.

The koto is a 21 string Japanese instrument (similar to a zither), that is

played on a horizontal plane (kind of like vibes). Masaoka, who works out

of San Francisco, performs in many different musical contexts, including

Western classical music, Japanese folk and avant-garde jazz. She has also

made a reputation playing in an electronic experimental idiom. The Monk

recording is a trio date which features the great Andrew Cyrille on drums

and the formidable Reggie Workman on bass (rhythm sections don't get any

better than this). This is easily the most distinctive Monk tribute that

I've heard and also one of the best. The koto, in Masaoka's hands, sounds

perfectly suited for Monk's quirky angular compositions. Lastly, I would

also highly recommend the two highly varied and cerebral recordings,

Memorophilia and Architextures by Berkeley-based pianist extraordinaire

Vijay Iyer. Iyer is the subject of a separate feature in this issue.

One of my favorite recordings of the last couple of years is a CD by

kotoist Miya Masaoka, called Monk's Japanese Folk Song. This superb

collection consists of compositions penned or inspired by Thelonious Monk.

The koto is a 21 string Japanese instrument (similar to a zither), that is

played on a horizontal plane (kind of like vibes). Masaoka, who works out

of San Francisco, performs in many different musical contexts, including

Western classical music, Japanese folk and avant-garde jazz. She has also

made a reputation playing in an electronic experimental idiom. The Monk

recording is a trio date which features the great Andrew Cyrille on drums

and the formidable Reggie Workman on bass (rhythm sections don't get any

better than this). This is easily the most distinctive Monk tribute that

I've heard and also one of the best. The koto, in Masaoka's hands, sounds

perfectly suited for Monk's quirky angular compositions. Lastly, I would

also highly recommend the two highly varied and cerebral recordings,

Memorophilia and Architextures by Berkeley-based pianist extraordinaire

Vijay Iyer. Iyer is the subject of a separate feature in this issue.

There is a rapidly growing and incredibly diverse body of recordings in the Asian Improv community. The recordings and artists who have been discussed in this feature are certainly not the only ones worthy of note. They merely reflect my personal preferences and selective knowledge of this fascinating idiom. The Asian Improv is a sign of the continuing vitality and creativity that constitutes modern jazz.

Recordings mentioned in this article:

Jon Jang and the Pan Asian Arkestra Tiananmen! (Soul Note, 1993)

The Jon Jang Sextet Two Flowers on a Stem (Soul Note, 1996)

Francis Wong The Great Wall (Asian Improv Records, 1994)

Fred Ho and the Monkey Orchestra Monkey, Part One (Koch Jazz, 1996)

Fred Ho and the Monkey Orchestra Monkey, Part Two (Koch Jazz, 1997)

Vijay Iyer Architextures (Asian Improv Records, 1996)

Vijay Iyer Memorophilia (Asian Improv Records, 1997)

Related web sites of interest:

- Asian Improv Arts: The record label which is home to many of the

great artists. This sites includes many links of interest.

- Vijay Iyer's home page, which

includes a wealth of information on his music and writings.

- The Varying Sounds of Asian American Jazz: An interesting

feature on Asian Improv Music written by Dan Oullete

- In Motion interview: A fascinating and richly detailed interview with Jon Jang and Francis Wong