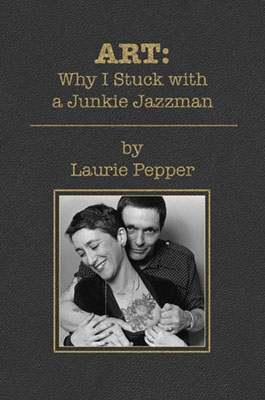

Art Pepper and Laurie Pepper

Their Unique Love Affair

by J.C. Lockwood

(December 2014)

Okay, the Art and Laurie story might not be Robert and Clara or Scott and Zelda, despite the, um, art that flowed from these tragic, troubled and profoundly productive hookups. But still, it is a love story for the ages, transversing, enveloping, the postwar and baby boom eras, the modern age, and is as powerful emotionally as it is strange and improbable. It's as significant, artistically, as anything the Schumanns or Fitzgeralds might have produced, classical elites be damned, but with a strange postmodern time signature, with Laurie, the sunny Cali-Cali, pink-diaper baby hipster, daughter of severe lefties, a photographer finding (and, this being a love story, resisting, at first) the true love she found at the cultish drug rehab center/business, where she landed after gobbling a bunch of pills and turning on the gas while listening to Dylan's "Visions of Joanna" in a failed suicide attempt, shortly after smashing up her car in a hash- and opium-fueled haze. She would play the role of '50s virgin with Art as love interest — a junkie jazzman, a jailbird, an alto saxophonist who had his wings clipped, who had, he thought, thrown away his life and the gift everyone drawn to a musical instrument dreams of, who challenged Bird and Trane without straying from his own sound, a flawed musician with a fastidious moral code, but one centered on two entrenched principles: mind your own business and never, ever snitch, a guy who had all but given up on music, on jazz, because of health and psychological issues. She kept him straight enough long enough to feel secure enough to not only dig out of his desperation, but to tell his story and, with her help, get past his apparent fate as poster boy for the evils of jazz and drugs. Ultimately, she saved his life, although she rejects the cartoonish wife-saint he made her out to be, saying "we rescued each other" — and, in the process, giving lie to the old Fitzgerald saw, that there are no second acts in America. As if Richard Nixon weren't proof enough.

Art Pepper's second act began, although he could not have known it at the time, when he stumbled, totally trashed, onto the campus of Synanon, the drug rehab center, making sure, loudly, everyone there knew that the raving lunatic in front of them, a guy who could barely stand up, was a total genius. Nah, he was never shy about talking up his talent. He was a bit of a blowhard, no pun intended, never shying away from telling anyone who would listen, in print in Straight Life, Pepper's 1979 oral history/autobiography, written by Laurie, or at death's door at Synanon, or in Don McGlynn's 1982 documentary Notes from a Jazz Survivor, that he was a cut above everyone who preceded him and, likely, all who would follow. "I'm a genius. I don't know anybody who plays better than I do," is how he laid it out for McGlynn. He had the goods, the talent, but, fact is, the guy had been mostly silent, musically, for the better part of a decade, from 1969, when he checked into Synanon, until 1976, when he released the "comeback" album, Living Legend, the title came from Les Koenig, the founder of Contemporary Records and long-time Pepper supporter, although Art would probably agree. Fact is that he fought his way back, releasing some three dozen high-quality albums in six years. He obviously had something to say. He was making up for lost time — and making sure he could provide for his family.

Laurie's second act has been a long time in the making. After being worn down essentially by Art's attentions at Synanon and finally freeing herself from the group, she became fascinated, almost obsessed, not with his music — not at first, anyhow, that would come later — but with his voice and the stories he told. This began an often-frustrating, at-times exhilarating seven-year effort to write and publish Straight Life, Art's autobiography, an unflinching look at jail, jazz and addiction. She, if not engineered or orchestrated, then managed the jazzman's improbable comeback and, for the past eight years, has been bringing Pepper's sound to a new generation of fans by launching Widow's Taste, her own record label, which has, to date, released a pile of new Pepper albums, previously unheard concerts and archival recordings. And, this year, she steps on the gas with Art: Why I Stuck with a Junkie Jazzman, which can be seen as a companion piece to Straight Life. The new book is a blunt, unsparing, at times bleak, tragic and sordid and, somehow, oddly hopeful, depiction of her frustrating, off-the-rails life with a crazy talented, flawed and broken musician, struggling, and ultimately failing to get past the addiction that defined, but did not cripple him. The book completes the long, strange trip that is the Art and Laurie love story, and the impossible, unbelievable story of the return of Art Pepper — and his wife's far-from-supporting role making it happen.

"If this book is about anything," she says, "it's about how stupid or crazy you can be and still survive. Even prevail. It's also about luck."

ART PARTS

Published independently last May, Artpicks up where Straight Life left off, transitioning from life outside, after jail, after Synanon, getting the autobiography finished and published, near the beginning of the comeback he didn't dare dream of if you're a junkie jazzman with a sheet and a seriously sketchy rep. It's a backstage pass. It's a story of finding a way back, despite yourself. It's richly detailed, nuanced and, looking at the guy, his quirks, the roadblocks, physical and emotional, a true test of faith for those closest to him. Which is why Laurie gets tagged with the "saint" label. It was a very bumpy ride, not the straight-up Lifetime network treatment (woman behind the man who saves him from the shadows of her own life) but way more than just the inspiring woman behind the man. "She pushed me, in music, and she took care of a lot of things I couldn't deal with," Art says in Straight Life, obliquely referencing the ugly side, the business side of art.

In the memoir, diehard fans and jazz junkies, in the metaphorical sense, may have some of the same frustrations with the Artas they might have had with Straight Life — lack of detail on his early musical training and influences, and, perhaps more importantly in this tell-all age, the lack of backstage dirt. Straight Life is tell-all, but only about Pepper's life. In Art, Laurie has plenty to say about George Cables, Art's favorite pianist, and has a lot of stuff about longtime Pepper sideman Milcho Leviev. There's some sniping about sidemen playing ballads in double-time, which particularly peeved Pepper or, a rare gem, a little story about vibist Gary Burton dropping a dime on Pepper during a clinic, for having a little, um, altitude, being a little tipsy, besmirching — or, one might say, living up to — the reputation of jazz musicians everywhere with his sordid ways ("I found that hysterically funny," she writes. "Jazz musicians' reputations? No wonder jazz is moribund"). But neither book has much to say about Art's early training or influences or backstage backbiting — and you gotta figure, guy's got the goods, besmirched reputation and all. What, if anything, he knew, he took to a much-too-early grave in 1982, at the age of 56.

He never listened to jazz at home or in the car, and listening to contemporary players made him nervous, jealous, Laurie writes, of what seemed to him unearned popularity or, more to the point, unearned popularity that could have been his. He rarely talked about music or his influences. Fans, she writes, "had no idea how much I had to nag to get him to say anything at all," she says.

At the same time, it has plenty of stuff that perhaps you don't need to know, or want to know, like how Art called Laurie "Mom-Mom," which is kinda creepy — and, worse, that he liked baby-talking with his sweetie-kins. Or that in addition to the methadone hidden in a shampoo bottle in Laurie's travel pack for out-of-country touring, he also brought Chloraseptic for his chronically raw mouth, foot powder for conditions thankfully never mentioned, and three kinds of laxative. This information that tells you, instinctively, to flee, but the most disgusting kind of prurient interest makes you wonder, why three kinds? Or that he favorited a woman's cologne. Or that he was buried in a pretty coffin, pearl gray lined with pink satin, which Laurie picked out because Art "liked pretty things." Or that he dug Doris Day, Steve Lawrence and, yikes, Barbra Streisand. But he did. "He loved singers, he envied their ability in music and words to to deal directly with emotions. That was his currency," Laurie writes.

Here's the AP shorthand: Born in Gardena, Calif., in 1925 to a violent, drunken family — despite his mother's best efforts to induce a miscarriage, according to the jazzman ("She lost. I won," he said in Straight Life). Packed off to live with his grandmother. Grew up in San Pedro, a major L.A. seaport that he would be able to see, many years later, from his cell in federal stir on Terminal Island. Hot shot clarinetist, switched to saxophone. Performed with Benny Carter and Lee Young as a pup, recorded with Stan Kenton when he was 17 years old. A phenom, the kind of guy you'd wanna strangle if you had any musical ambitions at all. Cue Salieri. Never studied. Never practiced. He was "one of those people. I knew it was there. All I had to do was reach out for it. Just do it," he said in Straight Life. Influenced, as a young man by Artie Shaw. Loved his technique, his sound. Loved the seemingly glamorous lifestyle that went with it. Dug swing-era jazzman Jimmy Lunceford, his full sound, the way he moaned through the horn. Johnny Hodges, of course, for the way he played ballads. But somehow he managed to hold onto himself musically. "I never intended to play like any of these people. Never," he said. Occasionally he'd pick up transcriptions, but it "wasn't me and it had no meaning to me at all. All of these people influenced me subconsciously, but I didn't feel like any of them, and I didn't play like any of them," he said in Straight Life. Heard Lester Young playing with Basie. "I dug the things he did, but I didn't want to ape him," he said. Joined the Kenton band in the '40s. Toured, got some attention. Drafted in 1943, served as an MP in London. Played with some British jazz bands. Picked up where he left off after the war, with Kenton. By then, the jazz world had changed again, and, away from the bandstand, he was a little bit lost. Wasn't hep to Bird or Diz - did not dig bebop. "I didn't want to play that way at all," he said in Straight Life. But it was de rigueur and had to be dealt with in some way. "I decided the only thing I could do is just practice and play and play and develop my own thing."

He left Kenton in the early '50's, struck out on his own and — the 800-pound gorilla in the room — developed the nasty habit that, perhaps as much as his sound, came to define him, followed by all-but-inevitable hospitalizations and incarcerations in state and federal prison, for possession, track marks. But somehow, he still managed to put out more than two dozen albums through the ‘50's, including monster releases like Meets the Rhythm Section and Gettin' Together with the Miles Davis rhythm section, during a long, productive association with Les Koenig — "probably the only honest man in the record business at that time," Laurie writes in Art— and Contemporary Records, which carried him into the '60's. Which is when it all started coming undone.

Art did three bids during the Age of Aquarius — all told, more than four years. In 1966, he had just gotten out of San Quentin, for the last time, it turns out, although smart money would have predicted otherwise. Like a lot of cats, he was surveying the new scene, trying to figure out where he fit in, how he could survive. He didn't own a horn and could only scrape together enough cash for one, so he bought a tenor, telling himself that, if he wanted to live and work in post-Beatles America, he had to play rock. But what he really wanted to do, he said in Straight Life, was to play like Coltrane. In 1968, he was in the Buddy Rich band, playing a loaner alto, "blowing the blues, really shouting," and thought that he had finally found his voice. "Then I realized that I had almost lost myself. Something had protected me all these years, but Trane was so strong, he almost destroyed me." That lasted about four years, but it wasn't a blind musical alley. It was a freeing experience. "It enabled me to be more adventurous, to extend myself note wise and emotionally. It enabled me to break through the inhibitions that for a long time kept me from growing and developing." But when he reunited with the alto, he realized, "if you don't play yourself, you're nothing. Since that day, I've been playing what I felt, regardless of what people around me were playing, or how they thought I should sound."

Plenty of his old fans were happy enough to see "that" Art Pepper go away. Laurie writes: The primal squawking, the wild, raw sound was so distant from the sweet, lyrical sound he was known for." But the "old" Art would not return. It became a question of reconciling his old lyrical self and new expressionistic wild influences and ideas. "My argument," Laurie writes, "was not how outside, atonal, arrhythmic he should get, but how much any of that was called for on any given song. I fought for meaning, symmetry and swing."

SAINTS AND SINNERS

Like she says, Laurie may have saved Art, or not, or maybe they saved each other, but she wasn't a saint. Whatever. Fact is, she walked into Synanon, and her relationship with Art, with baggage of her own. Born 1940. Studied music with dreams of being the next Billie Holiday, would have settled for Anita O'Day. Married young, married badly. She had become estranged from her daughter Maggie, 4. Worked as a staff photographer the L.A. Free Press. Subjects included Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, the Fugs. Kind of a wild child? Yeah, it was the ‘60's, there were issues of, you know, substance(s). She was 28 years old when she checked into Synanon with a "chaotic, raving, grieving, ravenous heart, with the social habits of a feral adolescent, and just enough self-knowledge to despise myself." She came out three and a half years later as a "more or less civilized and satisfied adult." For folks doing the math, she was 14 years younger than Art when she met him.

Art showed up about a year into her stint and began his pursuit of her. Art wasn't a fan of Synanon. The so-called therapeutic "games" seemed like snitch-bait to him, but he hung in for about three years before bailing. Laurie followed him into the world Synanon said would kill her shortly after that. They moved in together, continuing their Synanon-sanctioned relationship.

He was about as happily boring as he could be. He was an accountant. Didn't play, hadn't for a while, aside from an occasional on-campus dance back at Synanon. Didn't even own a horn. He kept his distance from the scene, figuring it would drag him down. He'd spend hours sitting around, staring at the tube. He didn't want to play music, she says, because it brought up old bad feelings, guilt for wasting his life.

Laurie, who had fallen in love with the sound of Art's voice, as an instrument, as he told his stories, on the inside, at Synanon, got Art to commit to an interview to tell his story. She never thought she could save or change him, but had gotten it into her head that she could help him tell his story and, in the process, save herself. "I thought I might have finally found a way to satisfy myself, to justify my existence," she writes.

Originally called Righteous People, prison slang for stand-up, Straight Life was a strange literary bird: an autobiography written by two people, incorporating oral history techniques, with Laurie lining up the other people in Art's life for their comments, which are sometimes at odds with the narrative. Initially, she resisted putting her name on it because, first, she wanted the focus on Art, but also because she "feared criticism like I feared death," she says. "I didn't try for praise in case I got the opposite." Art never saw the book in any pre-publication form: he didn't want to see the truths it told and how people would react. It scared him, putting it all out there, but he kept his hands off. "He trusted me, absolutely, with his life, his health, history and how that was finally told," she writes.

Getting the book published seemed like a no-brainer because Art was "so charismatic, and his life was so sordid, scary, so romantic and sexy (that) the world would agree with me," she says. But in the real world, not so much. "It was an idea mostly felt," she writes. Meaning nobody much cared about "a tape-recorded transcript of limited appeal only to jazz aficionados," which is how one rejection laid it out. Even her friends gave her the "most hedged" of approvals. "I felt deep down that I might be full of shit," she writes. "Who was I anyhow? I know I must have been crushed by these rejections, but I have no memory of being crushed. I had a tendency not to notice what I feel. I have a genius for busily distracting myself." And, Art being Art, being an addict, the work came with its own special challenges. He would get loaded for some of the sessions, sometimes nodding out. She'd watch the ash growing on his cigarette, dropping to his shirt, and get furious, finding him "repulsive and stupid." But forgiven. He got loaded not because he liked it, she says, but also to hush the self-critical voice in his head and the doubt in his heart. "He often dismissed his best work when he was sober, but delighted in less exciting stuff," she says. "His language, his directness, shocked and stirred me."

SYNANON, SYMBIOSIS

So, Art meets Laurie in Synanon. The place that was supposed to save them couldn't. They escaped, Art first, then Laurie. Then Laurie saved Art, or they saved each other, whatever, and lived happily ever after. Right? Well, no. Not exactly. Not at all. Art was an addict. Always. Clean? No, sir. He was an addict from age 25, when he did heroin for the first time in Chicago, on tour with Kenton. Writing in Straight Life, he was romanticizing that shooting smack was "like finding god, like finding love. It solves everything." Without actually solving anything, of course. He maintained on legally prescribed methadone, supplemented with coke, or pretty much anything he could lay his hands on (and get past Laurie) and, proving to be the biggest problem in their lives, alcohol. Booze was the worst. "Art," she writes, "was a stupid, asinine drunk prone to weird and sudden fits of anger." She remembers him as "a contagious presence whose moods you felt if you were near him." The life pushed her close to the edge. "I don't know how crazy I was, but I was fully aware how close to the edge Art was at any given time." His "backslidings were so creative and original that they never ceased to throw me," she writes. He had "a bitterness and a serious anger he cherished and loved to express. Which got him nowhere." She loved him and hated him. "I was overwhelmed by his criminality, his career, his anxieties, his demands, and I was completely dependent, myself, which is horrible, because despite his good intentions and his growing fame, his growing alcohol and drug use and his terrible health made him completely unreliable."

COMEBACK TRAIL

When she began her life with Art, there was no thought of a big comeback. Art didn't own an instrument and showed no immediate inclination to jump back into the scene, which, she writes, he actually feared. He seemed happy enough hanging at home, polishing his shoes, watching the tube. He seemed destined to be a footnote. Then, she writes, "someone found out that Art was still alive and everything changed, it seemed, in a single day."

It began with an invitation "out of nowhere," to work a clarinet clinic. Clarinet was his first instrument; he had doubled on it with Kenton. But he didn't have a clarinet — any instrument, in fact. He borrowed a battered instrument and did the clinic, where he ran into a company rep — and fan —for French-made Buffet Horns, who hooked Art up big time: silver flute, clarinet, tenor and alto sax. He started doing clinics and casuals, private, often corporate, gigs — all this, in hindsight, piggybacking with Contemporary and Koenig's release of The Way It Was, a collection of unreleased sessions, outtakes from four separate bands from the 1950's. "It knocked me out because it swung so hard," Laurie says. But it was his treatment of ballads, his stock in trade, she says, that really blew her away. "He gave a voice to everyone's grief and longing, with that pretty sound he had, the most lyrical in jazz," she writes. "He'd tell you all your problems and make you see the beauty in your sorrow. He turned it into something that ennobled his emotion and gave sublimity to ours." She was still deep into the Straight Life story, but both would soon be caught up in a dizzying comeback, beginning in 1976 with Living Legend, recorded old school style, in a single day. But this, it was clear, would not be the re-emergence of the pretty boy with the sweet, lyrical sound from the ‘50s. The cover shows a guy who had been clearly beat up by life, someone who had lived and won, barely. He looked, well, like a jailbird, with a black jeans, a torn-up tee, tats visible and worn proudly. He looked like he just had been shaken from a nod and handed a saxophone.

And what, besides a much-needed break, finally got him off his ass, musically? "He wanted to be heard, to make up for all the time he lost, to be recorded and remembered," she writes. And, of course, there was the money. "We needed it." And anyway, he had a working class mindset. His worth was linked to his earning ability, to the reality and the public perception of how well he took care of his family, Laurie and the two cats. And he knew time was short. Or, as Art said in Straight Life, he felt "a real sense of urgency because I feel something pulling at me. I have a strong feeling that I'm not going to live too much longer. And, although I have a lot of reasons to feel that way physically, this is more than a physical thing, I can sense that I'm becoming like another person. I can almost touch it. It's becoming real."

Funny thing is, even after they got together, Laurie wasn't especially a fan. Snotty elites at university listened to the "less melodic, more cerebral" East Coast stuff. "Actually, I preferred the West Coast vibe," she says. "I loved the Chico Hamilton Quintet, and you can't get more West Coasty than that." But she didn't hear Art because she was hanging out "with all those little snobs," she said in a recent e-mail exchange.

And, perhaps even funnier, the sound of his sax isn't what made her heart go thump-thump. It was the sound of his voice, the stories he told. She was in love with the guy, not the music — and the guy was not even "that" guy anymore.

STRAIGHT SHOOTING

Straight Life, finally published by Schirmer Books in 1979, making it something of an exclamation point to the comeback, rather than the opening salvo, was a critical success. It was reissued with a lengthy afterword by Da Capo Press in 1996. Over the years, Laurie has had a few nibbles from Hollywood for the Straight Life story, but she never signed off because the treatments felt, well, cheap and obvious — tough, street-smart jazzman with a habit on the hardscrabble streets of jazz town. Which, she admits, he probably would have liked. "He had the sound of an angel," she writes, "but wanted to be a bad ass." But the reps wouldn't even commit to real-life storyline — or, to using Art's music — so she has always passed.

With the book finally published, a major chapter of her life had closed. It was "the death of the best job" she ever had, but, with the endless babysitting, the necessary micromanaging of Art's day-to-day and performance and recording schedule, she had plenty to keep her busy, a challenge bordering on sainthood, and that very nearly pushed her over the edge — and amused and occasionally charmed her at the same time.

After his death in 1982, she was "a bit lost," emotionally and financially, she says. Art's financial world was tied up in probate. "I didn't know what would happen next," she says.

In the end, Down Beat elected their favorite whipping boy into the Hall of Fame — after he died, just like he said they would. Laurie negotiated the legal minefield that is probate, sorted out publishing, got the labels to cough up royalties — eventually. And she was able to get on with her life. Eventually.

But why so long for the follow-up?

"Life intervened," she said in a recent phone interview. The immediate problems of probate and publishing, royalties, jumping through legal hoops, surviving. Family issues. Getting sober. "That's important," she says. She started working with Artist Way group about a decade ago, which helped her get over the self-critical part, "that if it's not absolutely perfect it's not worth doing," the workshops freeing her up to do "any silly shit I wanted," she says. "It freed me up to play." Later, she worked with Audrey Bilger, professor of English at Clairmont University.

She formed Widow's Taste, which has released eight albums in as many years — a ninth is expected in early 2015. The albums will continue coming out "every year as long as there's interest." She has a vault of music. Art encouraged her to buy recording gear, and she was a compulsive recorder. She also has the digital collections of the crazy completists. She also writes a blog, helping her keep up with fans. And another book sometime in the future, the current memoir only a portion of a much larger piece. "There's too much to do," she says.

BOTTOM LINE

So, why did she stay with a junkie jazzman, a guy trapped by his reputation and his addictions, who nearly pushed her over the edge, physically and emotionally, in what most, if not all, viewers would view as an inevitable downward spiral? "It was very exciting. I wouldn't recommend it for people over 40 years old," she says. Why? Because he seduced her, because he inspired her, because he loved her and because life with Art was never a dull moment. But, in a word, love. "No sacrifice was too great," she said via phone interview. "I loved him so much."

And, of course, there was the music.

The two original tunes on Living Legend, Art's comeback album, both wink at Laurie: "Samba Mom Mom" — "Mom-Mom" being his somewhat creepy term of endearment for her — and "What Laurie Likes," an upbeat, jazz-rock composition, which, Laurie says now, "Laurie really does like." But she has different AP favorites, singling out Winter Moon, the 1981 strings and ballads album built around the Hoagy Carmichael tune of the same name that includes "Prisoner," the love theme from "Eyes of Laura Mars," the 1978 film starring Faye Dunaway and Tommy Lee Jones, and a minor hit for South Park nemesis Barbra Streisand, which is at the top of the list. There's Straight Life, of course — classic Art and "just an incredible album," she says. And, of course, the 1977 Village Vanguard performances, originally a three-disc, bumped up to nine discs in the later, complete collection — but especially the heartbreaking "Goodbye," dedicated to Pepper pal Hampton Hawes," a fellow West Coast player, a pianist who had a sadly similar non-musical biography, who died that year. Among the eight Widow's Taste albums, she fancies most the 1981 Croydon, England, performance on Art Pepper: Unreleased Art Vol. III, Croydon Concert, featuring the rhythm section that made up the Art Pepper Quartet from 1978 through most of 1981 — pianist Milcho Leviev, bassist Bob Magnusson and drummer Carl Burnett. It was the third Widow's Taste release, capturing a "consistently sublime" performance. She has also "reclaimed" at least one pirated album: Art Pepper: Jazz Showcase, Chicago, a live show recorded shortly before the Vanguard sessions. Each disc comes with extensive liner notes, full of backstage detail.

She remembers Art saying that playing jazz was like an exorcism and that, she says, when he was on, is exactly what he did. "He summoned up his demons to demolish them. He mined his pain, his confusion, his desperation and grief (also his passion, tenderness and joy). He connected with his audience and gave form to their feeling. He was an artist and he won the battle every time." And he was almost always on, no matter how off the rails he was; even when it looked like be wouldn't be able to even make it to the stage. "Then Art put his horn to his lips and played like an angel," she writes, making you "realize you don't know anything. It shocks and it empties you ... I saw it happen many times. It never failed to stun me. He stumbled to the bandstand, and then God took over, revealing where the gift was always from."

You can buy Pepper's albums at http://bit.ly/BuyArtPepper or http://www.cdbaby.com/Artist/ArtPepper

There's a pile of recordings at http://artpepper.bandcamp.com — full-length Widow's Taste recordings and a pile of free MP3 downloads. Art: Why I Stuck with a Junkie Jazzman and Straight Life are available through Amazon. Laurie's blog, where you can find free downloads and order the book is at http://artpeppermusic.blogspot.com/.